The Emergence of New Regions in Transition Romania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Identities of the Catholic Communities in the 18Th Century T Wallachia

Revista Română de Studii Baltice și Nordice / The Romanian Journal for Baltic and Nordic Studies, ISSN 2067-1725, Vol. 9, Issue 1 (2017): pp. 71-82 HE IDENTITIES OF THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITIES IN THE 18TH CENTURY T WALLACHIA Alexandru Ciocîltan „Nicolae Iorga” Institute of History, Romanian Academy, Email: [email protected] Acknowledgements This paper is based on the presentation made at the Sixth international conference on Baltic and Nordic Studies in Romania Historical memory, the politics of memory and cultural identity: Romania, Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea region in comparison, hosted by Ovidius University of Constanţa (Romania) and the Romanian Association for Baltic and Nordic Studies, May 22-23, 2015. This research was financed by the project „MINERVA – Cooperare pentru cariera de elită în cercetarea doctorală şi post-doctorală”, contract code: POSDRU/159/1.5/S/137832, co-financed by the European Social Fund, Sectorial Operational Programme Human Resources 2007-2013. Abstract: The Catholic communities in the 18th century Wallachia although belonging to the same denomination are diverse by language, ethnic origin and historical evolution. The oldest community was founded in Câmpulung in the second half of the 13th century by Transylvanian Saxons. At the beginning of the 17th century the Saxons lost their mother tongue and adopted the Romanian as colloquial language. Other communities were founded by Catholic Bulgarians who crossed the Danube in 1688, after the defeat of their rebellion by the Ottomans. The refugees came from four market-towns of north-western Bulgaria: Čiprovci, Kopilovci, Železna and Klisura. The Paulicians, a distinct group of Catholics from Bulgaria, settled north of the Danube during the 17th and 18th centuries. -

Media Influence Matrix Romania

N O V E M B E R 2 0 1 9 MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: ROMANIA Author: Dumitrita Holdis Editor: Marius Dragomir Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2019 About CMDS About the authors The Center for Media, Data and Society Dumitrita Holdis works as a researcher for the (CMDS) is a research center for the study of Center for Media, Data and Society at CEU. media, communication, and information Previously she has been co-managing the “Sound policy and its impact on society and Relations” project, while teaching courses and practice. Founded in 2004 as the Center for conducting research on academic podcasting. Media and Communication Studies, CMDS She has done research also on media is part of Central European University’s representation, migration, and labour School of Public Policy and serves as a focal integration. She holds a BA in Sociology from point for an international network of the Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca and a acclaimed scholars, research institutions and activists. MA degree in Sociology and Social Anthropology from the Central European University. She also has professional background in project management and administration. She CMDS ADVISORY BOARD has worked and lived in Romania, Hungary, France and Turkey. Clara-Luz Álvarez Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Monroe Price Marius Dragomir is the Director of the Center Anya Schiffrin for Media, Data and Society. He previously Stefaan G. Verhulst worked for the Open Society Foundations (OSF) for over a decade. Since 2007, he has managed the research and policy portfolio of the Program on Independent Journalism (PIJ), formerly the Network Media Program (NMP), in London. -

George Toader

BIBLIOTECA IULIA HASDEU A. LITERATURA ROMANA CLASICA SI CONTEMPORANA 1. Opere alese – Vol. I de Mihail Eminescu – Editura pentru literatura 1964 2. Romanii supt Mihai-Voievod Viteazul - Vol. I, II de Nicolae Balcescu Editura Tineretului 1967 3. Avatarii faraonului Tla – Teza de doctorat – de George Calinescu Editura Junimea, Iasi 1979 4. Domnisoara din strada Neptun de Felix Aderca - Editura Minerva 1982 5. Eficienta in 7 trepte sau Un abecedat al intelepciunii de Stephen R Covey Editura ALLFA, 2000 6. Explicatie si intelegere – Vol.1 de Teodor Dima Editura Stiintifica si Enciclopedica 1980 7. Gutenberg sau Marconi? de Neagu Udroiu – Editura Albatros 1981 8. Arta prozatorilor romani de Tudor Vianu – Editura Albatros 1977 9. Amintiri literare de Mihail Sadoveanu – Editura Minerva 1970 10. Fire de tort de George Cosbuc – Editura pentru literatura 1969 11. Piatra teiului de Alecu Russo – Editura pentru literatura 1967 12. Paradoxala aventura de I. Manzatu – Editura Tineretului 1962 13. Amintiri, povesti, povestiri de Ion Creanga Editura de stat pentru literatura si arta 1960 14. Mastile lui Goethe de Eugen Barbu - Editura pentru literatura 1967 15. Legendele Olimpului de Alexandru Mitru – Editura Tineretului 1962 16. Studii de estetica de C. Dimitrescu – Iasi – Editura Stiintifica 1974 2 17. Un fluture pe lampa de Paul Everac – Editura Eminescu 1974 18. Prietenie creatoare de Petre Panzaru – Editura Albatros 1976 19. Fabule de Aurel Baranga – Editura Eminescu 1977 20. Poezii de Nicolae Labis – Editura Minerva 1976 21. Poezii de Octavian Goga – Editura Minerva 1972 22. Teatru de Ion Luca Caragiale – Editura Minerva 1976 23. Satra de Zaharia Stancu – Editura pentru literatura 1969 24. -

Interethnic Discourses on Transylvania in the Periodical “Provincia”

DER DONAURAUM Andrea Miklósné Zakar Jahrgang 49 – Heft 1-2/2009 Interethnic Discourses on Transylvania in the Periodical “Provincia” Introduction The status quo of nation states has to face several significant challenges nowadays. One of these problems is bi-directional. The nation states formed in the 19th century are compelled to exist in an environment which oppresses their existence and functioning with new obstacles. They have to take account of the economic, social, cultural and com- munication changes and impacts caused by the globalisation processes. Through these transformations the state borders have become increasingly transparent and symbolic. The globalisation processes are enhanced by the appearance of macro-regional entities, such as the European Union with its single market. States taking part in the supranational decision-making mechanism of a macro-regional entity lose a part of their sovereignty. Under such circumstances the modern nation state is required to redefine itself, because its old “content” and operational mechanisms no longer assure appropriate function- ing. In addition the traditional confines of nation states have to face problems coming from the sub-national direction, raised by the regions themselves. In many cases sub-national territories, micro-regions or regions express a political will that sometimes results in the transformation of the nation state (e.g. the cases of Scotland, Catalonia or South Tyrol). “It seems that under the economic, politic and cultural influences of globalisation the traditional nation-state of the 19th century is too complex to resolve the problems of communities living on the sub-national (local and regional) level. At the same time a nation-state is too small to influence the globalisation processes from above.”1 Coming from the level of regions, regionalism is a bottom-up process expressing the will of the society (or a part of the society) living on that territory. -

Fișa De Verificare Privind Îndeplinirea Standardelor Minimale Pentru Obținerea Abilitării

FIȘA DE VERIFICARE PRIVIND ÎNDEPLINIREA STANDARDELOR MINIMALE PENTRU OBȚINEREA ABILITĂRII CONFORM ORDINULUI MECȘ NR. 3121/2015 CONF. UNIV. DR. FLORE POP Indicatorul I 1 – Articole în reviste cotate ISI având un factor de impact f ≥ 0,1 Nr. Denumirea articolului Punctaj Punctaj crt. articol total Flore Pop, „Water Affairs, Climate Change and Disaster Risk 1 Reduction in Central and Eastern Europe. An example in 8,256 8,256 Education at a Transylvanian University”, Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, No. 45, 2015 – în curs de apariție Indicatorul I 2 – Articole în reviste cotate ISI cu factor de impact f ≤ 0,1 sau în reviste indexate în cel puțin 2 dintre bazele de date internaționale recunoscute Nr. Denumirea articolului Punctaj Punctaj crt. articol total Flore Pop, „Les circonstances culturelles et politiques des 1 débats philosophiques entre l’Est et l’Ouest dans les années 6 quarante. Dumitru Stăniloaie en dialogue avec Martin Heidegger et Karl Jaspers”, Transilvanian Review, Vol. XXIV, No. 3, 2015 – în curs de apariție Flore Pop, „Premisele cooperarii internationale pentru 2 utilizarea pasnica a energiei nucleare si progresele realizate 4 de dreptul nuclear”, Revista Transilvană de Studii Administrative, Nr. 1 (19), 2007, pp. 60-69 Flore Pop, „La coopération internationale et régionale 3 concernant la protection de l'environnement et l'apport du 4 droit nucléaire. L'exemple de la Mer Noire”, Revista Transilvană de Studii Administrative, Nr. 3 (15), 2005, pp. 107-117 Flore Pop, „Considerații generale privind implementarea 4 acquis-ului comunitar în România, în domeniul concurenței”, 4 Studia Universitatis Babes Bolyai – Politica, Nr. 1, 2005, pp. -

Creating Community Over the Net: a Case Study of Romanian Online Journalism Mihaela V

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Creating Community over the Net: A Case Study of Romanian Online Journalism Mihaela V. Nocasian Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION CREATING COMMUNITY OVER THE NET: A CASE STUDY OF ROMANIAN ONLINE JOURNALISM By MIHAELA V. NOCASIAN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Mihaela V. Nocasian defended on August 25, 2005. ________________________ Marilyn J. Young Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________ Gary Burnett Outside Committee Member ________________________ Davis Houck Committee Member ________________________ Andrew Opel Committee Member _________________________ Stephen D. McDowell Committee Member Approved: _____________________ Stephen D. McDowell, Chair, Department of Communication _____________________ John K. Mayo, Dean, College of Communication The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my mother, Anişoara, who taught me what it means to be compassionate. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The story of the Formula As community that I tell in this work would not have been possible without the support of those who believed in my abilities and offered me guidance, encouragement, and support. My committee members— Marilyn Young, Ph.D., Gary Burnett Ph.D., Stephen McDowell, Ph.D., Davis Houck, Ph.D., and Andrew Opel, Ph.D. — all offered valuable feedback during the various stages of completing this work. -

Abstract Sfirlea, Titus G

ABSTRACT SFIRLEA, TITUS G. “THE TRANSYLVANIAN SCHOOL: ENLIGHTENED INSTRUMENT OF ROMANIAN NATIONALISM.” (Under the direction of Dr. Steven Vincent). The end of the eighteen and the beginning of the nineteen centuries represented a period of national renaissance for the Romanian population within the Great Principality of Transylvania. The nation, within a span of under fifty years, documented its Latin origins, rewrote its history, language, and grammar, and attempted to educate and gain political rights for its members within the Habsburg Empire’s family of nations. Four Romanian intellectuals led this enormous endeavor and left their philosophical imprint on the politics and social structure of the newly forged nation: Samuil Micu, Gheorghe Şincai, Petru Maior, and Ion-Budai Deleanu. Together they formed a school of thought called the Transylvanian School. Micu, Maior, and Şincai (at least early in his career), under the inspiration of the ideas of enlightened absolutism reflected in the reign of Joseph II, advocated and worked tirelessly to introduce reforms from above as a means for national education and emancipation. Deleanu, fully influenced by a combination of ideas emanating from French Enlightenment and French revolutionary sources, argued that the Romanian population of Transylvania could achieve social and political rights only if they were willing to fight for them. THE TRANSYLVANIAN SCHOOL: ENLIGHTENED INSTRUMENT OF ROMANIAN NATIONALISM by Titus G. Sfirlea A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History Raleigh, NC 2005 Approved by: _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Anthony La Vopa Dr. -

Anti-Hungarian Manifestations in Romania

Editor: Attila Nagy ANTI-HUNGARIAN MANIFESTATIONS IN ROMANIA 2017–2018 2017 According to Dezső Buzogány university professor, one of the translators, the lawsuit issued in connection It is outrageous and against education, that the to the restitution of the Batthyaneum may last longer Hungarian section grade 5 of fine arts in the János than expected because the judge, who should have taken Apáczai Csere High School in Kolozsvár (Cluj- the decision in the case - is retiring in February and Napoca) has been dismissed. With this step taken, this case, that attracts significant interest, is to be taken the future of the only Hungarian fine arts section in over by someone else. Meanwhile, the analysis of the mid-Transylvania became compromised – stated the translation of the testament of bishop Ignác Batthyány Miklós Barabás Guild (Barabás Miklós Céh/Breasla by experts hired both by the plaintiff and by the Barabás Miklós) in its announcement. respondent, is still going on. It is only after this process The news of the dismissal of the class has had neg- that the court of Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia) can be ative echo abroad since the art training practiced at expected to pronounce a decision in the lawsuit in which Apáczai High School has gained recognition not only the Roman Catholic Church demanded the nullification at home but on an international scale as well. The an- of the decision of the restitution committee rejecting nouncement insists on the importance of insertion by restitution. The late bishop left his collection of unique the School Inspectorate of Kolozs (Cluj) County of a new value to the Catholic Church and Transylvania Province. -

Erasmus Students Welcome Guide

...I DEPARTAMENTUL DE RELAȚII INTERNAȚIONALE . Erasmus Students Welcome Guide CONTENTS: 1. Contact 2. Universitatea de Vest din Timişoara 3. Erasmus+ Programme 4. Erasmus Student Network Timişoara 5. Living in Timişoara 6. Useful Information CONTACT: UNIVERSITATEA DE VEST DIN TIMIŞOARA Address: Blvd. V. Pârvan 4, Timişoara – 300223, Timiş, România Web: http://www.uvt.ro/en/university/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/uvtromania Department of International Relations Opening hours: 8:00-16:00 Mon-Fri Room: 155B, 1st floor Phone: +40-256-592352 Fax: +40-256-592313 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.ri.uvt.ro/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/international.uvt Pro-Rector for International Relations and Institutional Communication: Professor Dana PETCU, PhD. Phone: +40-256-592 270 E-mail: [email protected] Director of Department of International Relations & Erasmus Institutional Coordinator: Andra-Mirona DRAGOTESC, PhD. Phone: +40-256-592352 E-mail: [email protected] Head of Erasmus Office: Oana-Roxana IVAN, PhD. Phone: +40-256-592372 E-mail: [email protected] Erasmus Outgoing Officer-studies: Cristina COJOCARU Phone: +40-256-592271 E-mail: [email protected] Erasmus Outgoing Officer-placements: Lucia URSU Phone: +40-256-592271 E-mail: [email protected] B-dul Vasile Pârvan, Nr. 4, 300223 Timişoara, România. PAGINA | 1 Telefon: 0256-592.303 Email: Tel. (Fax): +4 0256-592.352 (313), E-mail: contact@[email protected], www.ri.uvt.ro . Website: http://www.uvt.ro/ . ...I DEPARTAMENTUL DE RELAȚII INTERNAȚIONALE . Erasmus Incoming Officer: Horaţiu HOT Phone: +40-256-592271 E-mail: [email protected] UNIVERSITATEA DE VEST DIN TIMISOARA Welcome to Universitatea de Vest din Timişoara! You have chosen Universitatea de Vest din Timişoara to complete a part of your studies or you are about to do so. -

1 Protecţia Dreptului La Libertatea De Gândire Conştiinţă Şi Religie În Baza

Protecţia dreptului la libertatea de gândire conştiinţă şi religie în baza Convenţiei Europene a Drepturilor Omului Ghidul Consiliului Europei cu privire la drepturile Omului Consiliul Europei, Strasbourg 2012 Prefaţă 1 GHIDUL DREPTURILOR OMULUI AL CONSILIUL EUROPEI Jim Murdoch este Profesor de drept public la universitatea din Glasgow şi fostul Director al Şcolii de Drept. Interesele sale de cercetară sunt în domeniul drepturilor omului în context naţional şi European. El este un participant fidel la vizetele de studiu organizate de Consiliul Europei în statele din Europa central şi de est şi este în mod special interesat de mecanismele de implementare non-juridică a drepturilor omului. Opiniile expuse în această publicaţie aparţin autorului şi nu reprezintă poziţia Consiliului Europei. Ele nu reprezintă autoritate asupra instrumentelor legale menţionate în text şi nici o interpretare oficială care să oblige guvernele statelor membre, organele statutare ale Consiliului Europei şi orice alte organe instituite în virtutea Convenţiei Europene a Drepturilor Omului. Prefaţă 2 PROTECŢIA DREPTULUI LA LIBERTATEA DE GÂNDIRE CONŞTIINŢĂ LI RELIGIE Conţinut Articolul 9 Convenţia Europeană a Drepturi- Manifestarea religiei sau a convingerilor. lor Omului Aspectul de colectivitate al articolului 9. Aspectul de colectivitate al articolului 9 și recu- Prefaţă noașterea statutului de "victimă". Limite pentru domeniul de aplicare al articolului Libertatea de gândire, conştiinţă şi religie: 9. standarde internaţionale şi regionale. Întrebarea 2: Au existat careva interferenţe cu Interpretarea articolului 9 al Convenţiei: con- dreptul garantat in articolul 9? sideraţii generale. Obligaţii positive. Ocuparea forţei de muncă şi libertatea de gân- Introducere dire, conştiinţă şi religie. Permiterea recunoaşterii necesare a practicilor Aplicarea articolului9: lista de întrebări cheie. -

FINAL REPORT International Commission on the Holocaust In

FINAL REPORT of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania Presented to Romanian President Ion Iliescu November 11, 2004 Bucharest, Romania NOTE: The English text of this Report is currently in preparation for publication. © International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. All rights reserved. DISTORTION, NEGATIONISM, AND MINIMALIZATION OF THE HOLOCAUST IN POSTWAR ROMANIA Introduction This chapter reviews and analyzes the different forms of Holocaust distortion, denial, and minimalization in post-World War II Romania. It must be emphasized from the start that the analysis is based on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s definition of the Holocaust, which Commission members accepted as authoritative soon after the Commission was established. This definition1 does not leave room for doubt about the state-organized participation of Romania in the genocide against the Jews, since during the Second World War, Romania was among those allies and a collaborators of Nazi Germany that had a systematic plan for the persecution and annihilation of the Jewish population living on territories under their unmitigated control. In Romania’s specific case, an additional “target-population” subjected to or destined for genocide was the Romany minority. This chapter will employ an adequate conceptualization, using both updated recent studies on the Holocaust in general and new interpretations concerning this genocide in particular. Insofar as the employed conceptualization is concerned, two terminological clarifications are in order. First, “distortion” refers to attempts to use historical research on the dimensions and significance of the Holocaust either to diminish its significance or to serve political and propagandistic purposes. Although its use is not strictly confined to the Communist era, the term “distortion” is generally employed in reference to that period, during which historical research was completely subjected to controls by the Communist Party’s political censorship. -

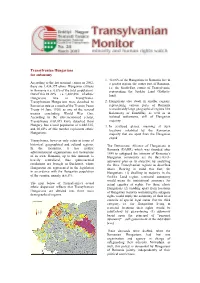

Transylvanian Hungarians for Autonomy 1

Transylvanian Hungarians for autonomy 1. 42,66% of the Hungarians in Romania live in According to the last national census in 2002, a greater region, the centre part of Romania, there are 1,434,377 ethnic Hungarian citizens i.e. the South-East corner of Transylvania, in Romania (i.e. 6.6% of the total population). representing the Szekler Land (Székely- Out of this 98.29% – i.e. 1,409,894 – of ethnic land). Hungarians live in Transylvania. Transylvanian Hungarians were detached to 2. Hungarians also dwell in smaller regions, Romanian rule as a result of the Trianon Peace representing various parts of Romania Treaty (4 June 1920) as one of the several (considerably large geographical regions like treaties concluding World War One. Kalotaszeg or Érmellék), as well as in According to the aforementioned census, isolated settlements, still of Hungarian Transylvania (103,093 km²), detached from majority. Hungary, has a total population of 6,888,515, 3. In scattered places, meaning at such and 20,46% of this number represents ethnic locations inhabited by the Romanian Hungarians. majority that are apart from the Hungarian chunk. Transylvania, however only exists in terms of historical, geographical and cultural regions. The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in In the meantime, it has neither Romania (DAHR) which was founded after administrational organizations, nor institutions 1989 to safeguard the interests of Romania’s of its own. Romania, up to this moment, is Hungarian community set the three-level- heavily centralized, thus quintessential autonomy plan as its objective by analyzing resolutions are brought in Bucharest, where the three Transylvanian regions as described Hungarians are represented in the legislation above.