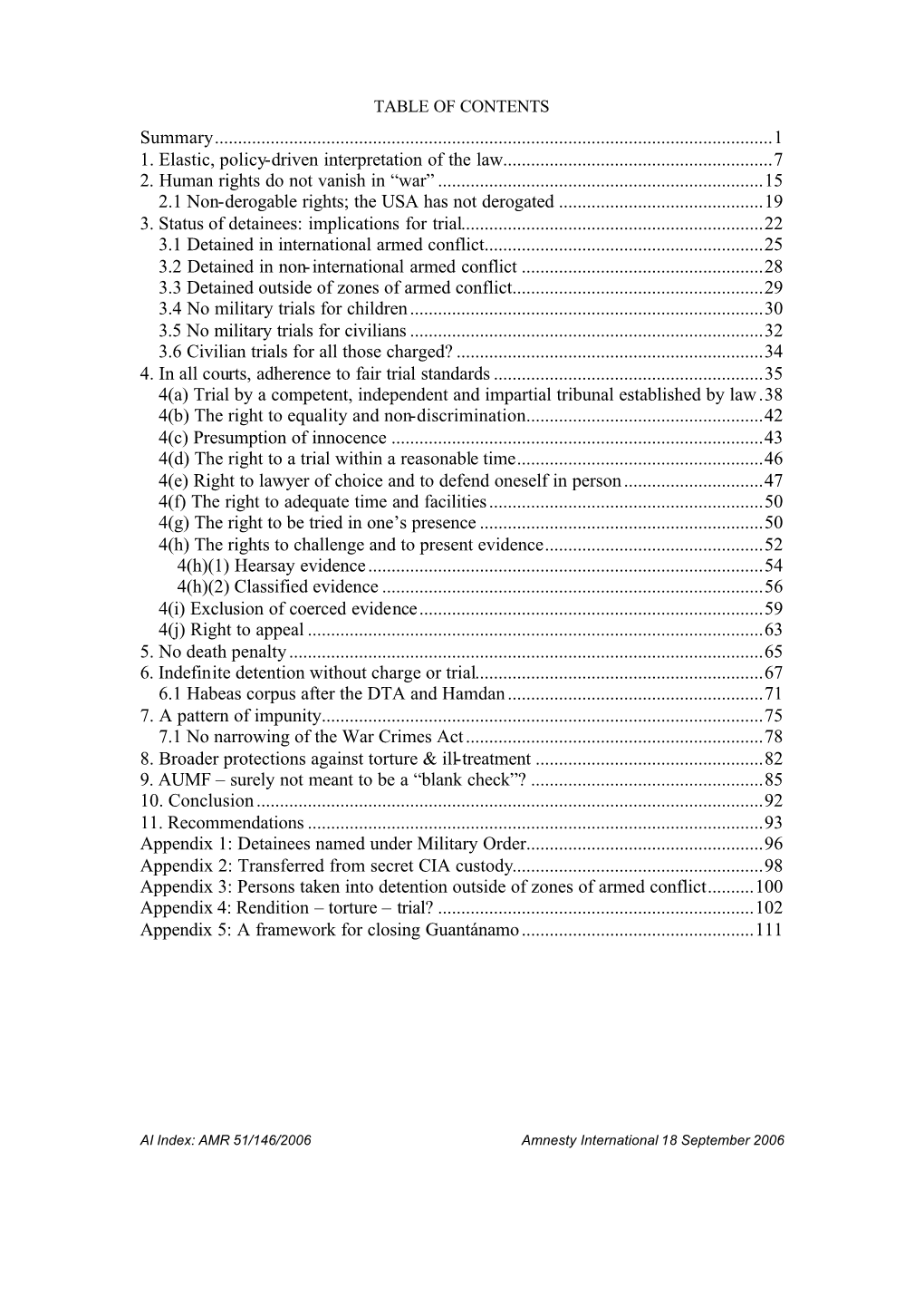

3. Status of Detainees: Implications for Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

A Review of the FBI's Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantanamo Bay, Mghanistan, and Iraq

Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 1 of 21 EXHIBIT 4 Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 2 of 21 U.S. Department ofJustice Office of the Inspector General A Review of the FBI's Involvement in and Observations of Detainee Interrogations in Guantanamo Bay, Mghanistan, and Iraq Oversight and Review Division Office of the Inspector General May 2008 UNCLASSIFIED Case 1:04-cv-04151-AKH Document 450-5 Filed 02/15/11 Page 3 of 21 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .i CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 I. Introduction l II. The OIG Investigation 2 III. Prior Reports Regarding Detainee Mistreatment 3 IV. Methodology of OIG Review of Knowledge of FBI Agents Regarding Detainee Treatment · 5 A. The OIG June 2005 Survey 5 B. OIG Selection of FBI Personnel for.Interviews 7 C. OIG Treatment of Military Conduct 7 V. Organization of the OIG Report 8 CHAPTER TWO: FACTUAL BACKGROUND 11 I. The Changing Role of the FBI After September 11 11 II. FBI Headquarters Organizational Structure for Military Zones 12 A. Counterterrorism Division 13 1. International Terrorism Operations Sections 13 2. Counterterrorism Operations Response Section 14 B. Critical Incident Response Group 15 C. Office of General Counsel. 15 III. Other DOJ Entities Involved in Overseas Detainee Matters 16 IV. Inter-Agency Entities and Agreements Relating to Detainee Matters. 16 A. The Policy Coordinating Committee 16 B. Inter-Agency Memorandums of Understanding 18 V. Background Regarding the FBI's Role in the Military Zones 19 A. -

Unclassified//For Public Release Unclassified//For Public Release

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR PUBLIC RELEASE --SESR-Efll-N0F0RN- Final Dispositions as of January 22, 2010 Guantanamo Review Dispositions Country ISN Name Decision of Origin AF 4 Abdul Haq Wasiq Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 6 Mullah Norullah Noori Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 7 Mullah Mohammed Fazl Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 560 Haji Wali Muhammed Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war, subject to further review by the Principals prior to the detainee's transfer to a detention facility in the United States. AF 579 Khairullah Said Wali Khairkhwa Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 753 Abdul Sahir Referred for prosecution. AF 762 Obaidullah Referred for prosecution. AF 782 Awai Gui Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 832 Mohammad Nabi Omari Continued detention pursuant to the Authorization for Use of Military Force (2001 ), as informed by principles of the laws of war. AF 850 Mohammed Hashim Transfer to a country outside the United States that will implement appropriate security measures. AF 899 Shawali Khan Transfer to • subject to appropriate security measures. -

Report on Public Forum

Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights, Freedoms and Democracy Report and Recommendations for Policy Direction of a Public Forum organized by the International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group Ottawa, February 17, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................2 ABOUT THE ICLMG .............................................................................................................2 BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................................3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .....................................................................................................4 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR POLICY DIRECTION ..........................................................14 PROCEEDINGS......................................................................................................................16 CONCLUDING REMARKS...................................................................................................84 ANNEXES...............................................................................................................................87 ANNEXE I: Membership of the ICLMG ANNEXE II: Program of the Public Forum ANNEXE III: List of Participants/Panelists Anti-Terrorism and the Security Agenda: Impacts on Rights Freedoms and Democracy 2 __________________________________________________________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Forum session reporting -

Making Sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: a Social Movement Perspective

\ WORKING PAPER 6\ 2017 Making sense of Daesh in Afghanistan: A social movement perspective Katja Mielke \ BICC Nick Miszak \ TLO Joint publication by \ WORKING PAPER 6 \ 2017 MAKING SENSE OF DAESH IN AFGHANISTAN: A SOCIAL MOVEMENT PERSPECTIVE \ K. MIELKE & N. MISZAK SUMMARY So-called Islamic State (IS or Daesh) in Iraq and Syria is widely interpreted as a terrorist phenomenon. The proclamation in late January 2015 of a Wilayat Kho- rasan, which includes Afghanistan and Pakistan, as an IS branch is commonly interpreted as a manifestation of Daesh's global ambition to erect an Islamic caliphate. Its expansion implies hierarchical order, command structures and financial flows as well as a transnational mobility of fighters, arms and recruits between Syria and Iraq, on the one hand, and Afghanistan–Pakistan, on the other. In this Working Paper, we take a (new) social movement perspective to investigate the processes and underlying dynamics of Daesh’s emergence in different parts of the country. By employing social movement concepts, such as opportunity structures, coalition-building, resource mobilization and framing, we disentangle the different types of resource mobilization and long-term conflicts that have merged into the phenomenon of Daesh in Afghanistan. In dialogue with other approaches to terrorism studies as well as peace, civil war and security studies, our analysis focuses on relations and interactions among various actors in the Afghan-Pakistan region and their translocal networks. The insight builds on a ten-month fieldwork-based research project conducted in four regions—east, west, north-east and north Afghanistan—during 2016. We find that Daesh in Afghanistan is a context-specific phenomenon that manifests differently in the various regions across the country and is embedded in a long- term transformation of the religious, cultural and political landscape in the cross-border region of Afghanistan–Pakistan. -

Us Air Force Governors Chapter Laureate Awards

US AIR FORCE GOVERNORS 1950-54 Harry G. Armstrong 1954-59 Dan C. Ogle 1958-63 Oliver K. Niess 1963-67 Richard L. Bohannon 1967-68 Kenneth E. Pletcher 1968-69 Henry C. Dorris 1969-70 Robert B. W. Smith 1971-73 Ernest J. Clark 1973-76 Dana G. King, Jr. 1976-78 Ernest J. Clark 1978-83 Murphy A. Chesney 1983-86 Gerald W. Parker 1986 Monte B. Miller, Maj. Gen. 1986-89 Alexander M. Sloan, Maj. Gen. 1989-92 Albert B. Briccetti, Col 1992-96 Charles K. Maffet, Col 1996-00 James M. Benge, Col 2000-04 Arnyce R. Pock, Col 2004-08 Kimberly P. May, Lt Col 2008-10 Vincent F. Carr, Col 2010-13 Rechell G. Rodriguez, Col 2013-17 William Hannah, Jr., Col 2017-Present Matthew B. Carroll, Col (ret) CHAPTER LAUREATE AWARDS 1992 Lt Gen Monte Miller 1993 Col Al Briccetti 1994 Lt Gen Alexander Sloan 1995 No Award 1996 BG (Ret) Gerald Parker 1997 Col (Ret) Kenneth Maffet 1998 Col (Ret) George Crawford 1999 Col (Ret) R. Neal Boswell 2000 Lt Gen (Ret) Murphy A. Chesney 2001 Col (Ret) George Meyer 2002 Col (Ret) Takeshi Wajima 2003 Meeting Cancelled 2004 Col (Ret) Jay Higgs 2005 Col (Ret) Jose Gutierrez-Nunez 2006 Col (Ret) Theodore Freeman 2007 No award 2008 Col (Ret) Matthew Dolan 2009 Col (Ret) John (Rick) Downs 2009 Col (Ret) John McManigle 2010 Col Arnyce Pock 2011 Col (Ret) Richard Winn 2012 Col (Ret) James Jacobson 2013 Col (Ret) Thomas Grau 2014 No award 2015 No award 2016 No award 2017 Col (Ret) Jay B. -

The Biden Administration Must Defend Americans Targeted by the International Criminal Court Steven Groves

BACKGROUNDER No. 3622 | MAY 17, 2021 MARGARET THATCHER CENTER FOR FREEDOM The Biden Administration Must Defend Americans Targeted by the International Criminal Court Steven Groves he Declaration of Independence cataloged the KEY TAKEAWAYS ways in which King George III infringed upon American liberties. Among King George’s Since its founding, the United States has T offenses listed in the Declaration was “Transporting tried to protect its citizens from legal us beyond the Seas to be tried for pretended Offences.” harassment and persecution by foreign courts. The king claimed the authority to seize American col- onists and force them to stand trial in Great Britain for criminal offenses allegedly committed in America. The Prosecutor of the International Almost 250 years later, another foreign tribunal— Criminal Court has compiled a secret annex listing American citizens to be the International Criminal Court (ICC), located in targeted for prosecution for alleged war The Hague in the Netherlands—is working toward crimes. issuing arrest warrants for American citizens for allegedly abusing detainees in Afghanistan. The court The Biden Administration should stop the is pursuing this course despite the fact that the United ICC from persisting in its misguided pros- States is not a party to the Rome Statute of the Inter- ecution of American citizens that have national Criminal Court and therefore not subject to already been investigated by the U.S. the ICC’s jurisdiction. This paper, in its entirety, can be found at http://report.heritage.org/bg3622 The Heritage Foundation | 214 Massachusetts Avenue, NE | Washington, DC 20002 | (202) 546-4400 | heritage.org Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of The Heritage Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress. -

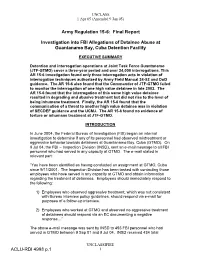

Army Regulation 15-6: Final Report Investigation Into FBI Allegations Of

UNCLASS 1 Apr 05 (Amended 9 Jun 05) Army Regulation 15-6: Final Report Investigation into FBI Allegations of Detainee Abuse at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba Detention Facility EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Detention and interrogation operations at Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) cover a three-year period and over 24,000 interrogations. This AR 15-6 investigation found only three interrogation acts in violation of interrogation techniques authorized by Army Field Manual 34-52 and DoD guidance. The AR 15-6 also found that the Commander of JTF-GTMO failed to monitor the interrogation of one high value detainee in late 2002. The AR 15-6 found that the interrogation of this same high value detainee resulted in degrading and abusive treatment but did not rise to the level of being inhumane treatment. Finally, the AR 15-6 found that the communication of a threat to another high value detainee was in violation of SECDEF guidance and the UCMJ. The AR 15-6 found no evidence of torture or inhumane treatment at JTF-GTMO. INTRODUCTION In June 2004, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) began an internal investigation to determine if any of its personnel had observed mistreatment or aggressive behavior towards detainees at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba (GTMO). On 9 Jul 04, the FBI – Inspection Division (INSD), sent an e-mail message to all FBI personnel who had served in any capacity at GTMO. The e-mail stated in relevant part: “You have been identified as having conducted an assignment at GTMO, Cuba since 9/11/2001. The Inspection Division has been tasked with contacting those employees who have served in any capacity at GTMO and obtain information regarding the treatment of detainees. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) SHAFIQ RASUL, et al. ) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-0299 (CKK) ) GEORGE WALKER BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) FAWZI KHALID ABDULLAH FAHAD ) AL ODAH, et al. ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-0828 (CKK) ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) ) MAMDOUH HABIB, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-1130 (CKK) ) GEORGE WALKER BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MURAT KURNAZ, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1135 (ESH) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) OMAR KHADR, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1136 (JDB) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MOAZZAM BEGG, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1137 (RMC) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MOURAD BENCHELLALI, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1142 (RJL) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) JAMIL EL-BENNA, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1144 (RWR) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) FALEN GHEREBI, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1164 (RBW) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) LAKHDAR BOUMEDIENE, et al.,) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1166 (RJL) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) SUHAIL ABDUL ANAM, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. -

“New Norms” and the Continuing Relevance of IHL in the Post-9/11

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (900), 1277–1293. The evolution of warfare doi:10.1017/S1816383116000138 The danger of “new norms” and the continuing relevance of IHL in the post-9/11 era Anna Di Lellio and Emanuele Castano Anna Di Lellio is a Professor of International Affairs at the New School of Public Engagement and New York University. Emanuele Castano is a Professor of Psychology at the New School for Social Research. Abstract In the post-9/11 era, the label “asymmetric wars” has often been used to question the relevance of certain aspects of international humanitarian law (IHL); to push for redefining the combatant/civilian distinction; and to try to reverse accepted norms such as the bans on torture and assassination. In this piece, we focused on legal and policy discussions in the United States and Israel because they better illustrate the dynamics of State-led “norm entrepreneurship”, or the attempt to propose opposing or modified norms as a revision of IHL. We argue that although these developments are to be taken seriously, they have not weakened the normative power of IHL or made it passé. On the contrary, they have made it more relevant than ever. IHL is not just a complex (and increasingly sophisticated) branch of law detached from reality. Rather, it is the embodiment of widely shared principles of morality and ethics, and stands as a normative “guardian” against processes of moral disengagement that make torture and the acceptance of civilian deaths more palatable. Keywords: IHL, asymmetric war, norm entrepreneurs, targeted killing, torture, terrorism, moral disengagement. -

AMERICA's CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 11

t I l AlLY r .... )k.fl ~FS A Ot:l ) lO~Ol R.. Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W. Yale-Loehr • M I GRAT i o~]~In AMERICA'S CHALLENGE: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity after September 11 .. AUTHORS Muzaffar A. Chishti Doris Meissner Demetrios G. Papademetriou Jay Peterzell Michael J. Wishnie Stephen W . Yale-Loehr MPI gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton in the preparation of this report. Copyright © 2003 Migration Policy Institute All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Migration Policy Institute. Migration Policy Institute Tel: 202-266-1940 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300 Fax:202-266-1900 Washington, DC 20036 USA www.migrationpolicy.org Printed in the United States of America Interior design by Creative Media Group at Corporate Press. Text set in Adobe Caslon Regular. "The very qualities that bring immigrants and refugees to this country in the thousands every day, made us vulnerable to the attack of September 11, but those are also the qualities that will make us victorious and unvanquished in the end." U.S. Solicitor General Theodore Olson Speech to the Federalist Society, Nov. 16, 2001. Mr. Olson's wife Barbara was one of the airplane passengers murdered on September 11. America's Challenge: Domestic Security, Civil Liberties, and National Unity After September 1 1 Table of Contents Foreword -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct.