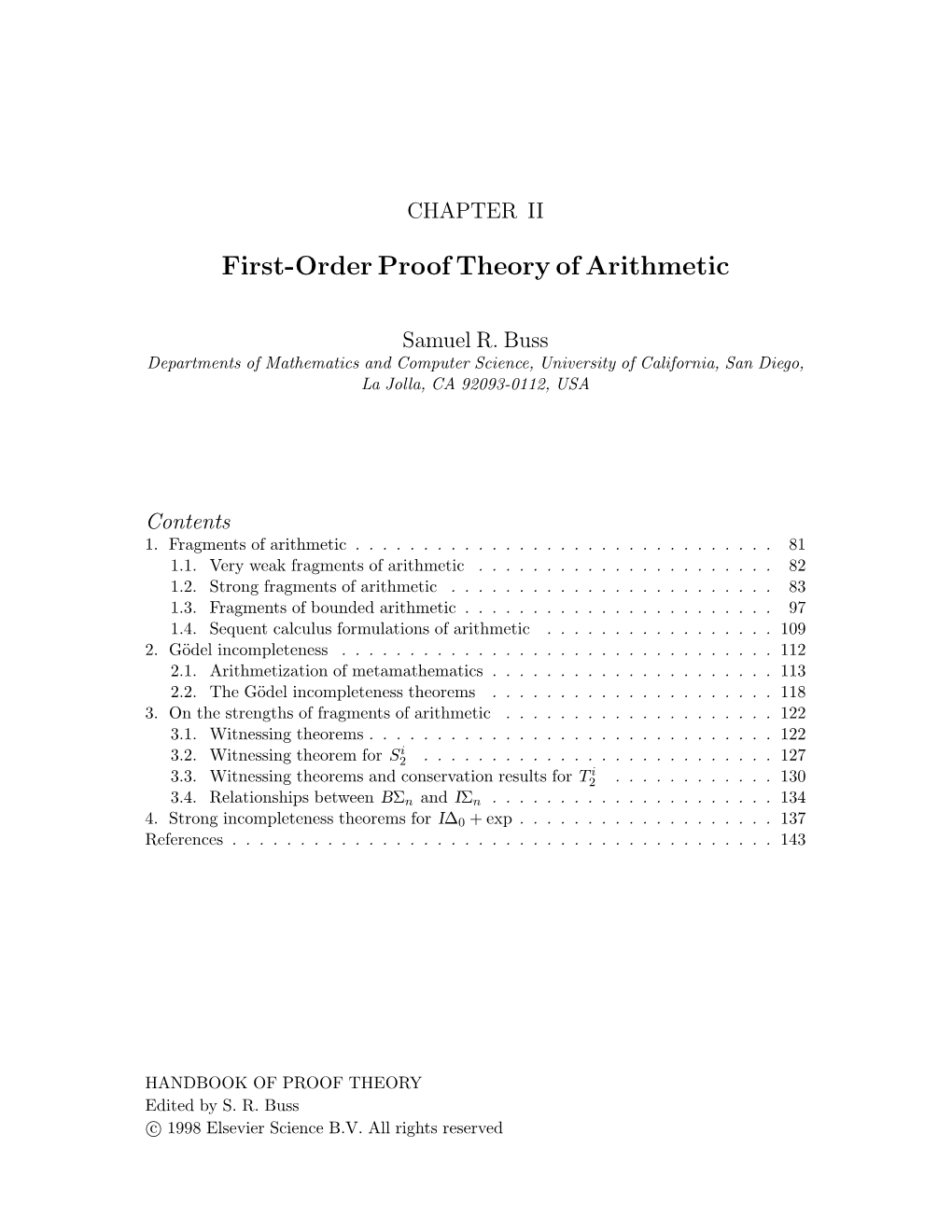

First-Order Proof Theory of Arithmetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REFERENCE in ARITHMETIC §1. to Prove His Famous First

REFERENCE IN ARITHMETIC LAVINIA PICOLLO Abstract. Self-reference has played a prominent role in the development of metamath- ematics in the past century, starting with G¨odel'sfirst incompleteness theorem. Given the nature of this and other results in the area, the informal understanding of self-reference in arithmetic has sufficed so far. Recently, however, it has been argued that for other related issues in metamathematics and philosophical logic a precise notion of self-reference and, more generally, reference, is actually required. These notions have been so far elusive and are surrounded by an aura of scepticism that has kept most philosophers away. In this paper I suggest we shouldn't give up all hope. First, I introduce the reader to these issues. Second, I discuss the conditions a good notion of reference in arithmetic must satisfy. Accordingly, I then introduce adequate notions of reference for the language of first-order arithmetic, which I show to be fruitful for addressing the aforementioned issues in metamathematics. x1. To prove his famous first incompleteness result for arithmetic, G¨odel[5] developed a technique called \arithmetization" or “g¨odelization".It consists in codifying the expressions of the language of arithmetic with numbers, so that the language can `talk' about its own formulae. Then, he constructed a sentence in the language that he described as stating its own unprovability in a system satisfying certain conditions,1 and showed this sentence to be undecidable in the system. His method led to enormous progress in metamathematics and computer science, but also in philosophical logic and other areas of philosophy where formal methods became popular. -

The Logic of Provability

The Logic of Provability Notes by R.J. Buehler Based on The Logic of Provability by George Boolos September 16, 2014 ii Contents Preface v 1 GL and Modal Logic1 1.1 Introduction..........................................1 1.2 Natural Deduction......................................2 1.2.1 ...........................................2 1.2.2 3 ...........................................2 1.3 Definitions and Terms....................................3 1.4 Normality...........................................4 1.5 Refining The System.....................................6 2 Peano Arithmetic 9 2.1 Introduction..........................................9 2.2 Basic Model Theory..................................... 10 2.3 The Theorems of PA..................................... 10 2.3.1 P-Terms........................................ 10 2.3.2Σ,Π, and∆ Formulas................................ 11 2.3.3 G¨odelNumbering................................... 12 2.3.4 Bew(x)........................................ 12 2.4 On the Choice of PA..................................... 13 3 The Box as Bew(x) 15 3.1 Realizations and Translations................................ 15 3.2 The Generalized Diagonal Lemma............................. 16 3.3 L¨ob'sTheorem........................................ 17 3.4 K4LR............................................. 19 3.5 The Box as Provability.................................... 20 3.6 GLS.............................................. 21 4 Model Theory for GL 23 5 Completeness & Decidability of GL 25 6 Canonical Models 27 7 On -

(Aka “Geometric”) Iff It Is Axiomatised by “Coherent Implications”

GEOMETRISATION OF FIRST-ORDER LOGIC ROY DYCKHOFF AND SARA NEGRI Abstract. That every first-order theory has a coherent conservative extension is regarded by some as obvious, even trivial, and by others as not at all obvious, but instead remarkable and valuable; the result is in any case neither sufficiently well-known nor easily found in the literature. Various approaches to the result are presented and discussed in detail, including one inspired by a problem in the proof theory of intermediate logics that led us to the proof of the present paper. It can be seen as a modification of Skolem's argument from 1920 for his \Normal Form" theorem. \Geometric" being the infinitary version of \coherent", it is further shown that every infinitary first-order theory, suitably restricted, has a geometric conservative extension, hence the title. The results are applied to simplify methods used in reasoning in and about modal and intermediate logics. We include also a new algorithm to generate special coherent implications from an axiom, designed to preserve the structure of formulae with relatively little use of normal forms. x1. Introduction. A theory is \coherent" (aka \geometric") iff it is axiomatised by \coherent implications", i.e. formulae of a certain simple syntactic form (given in Defini- tion 2.4). That every first-order theory has a coherent conservative extension is regarded by some as obvious (and trivial) and by others (including ourselves) as non- obvious, remarkable and valuable; it is neither well-enough known nor easily found in the literature. We came upon the result (and our first proof) while clarifying an argument from our paper [17]. -

Geometry and Categoricity∗

Geometry and Categoricity∗ John T. Baldwiny University of Illinois at Chicago July 5, 2010 1 Introduction The introduction of strongly minimal sets [BL71, Mar66] began the idea of the analysis of models of categorical first order theories in terms of combinatorial geometries. This analysis was made much more precise in Zilber’s early work (collected in [Zil91]). Shelah introduced the idea of studying certain classes of stable theories by a notion of independence, which generalizes a combinatorial geometry, and characterizes models as being prime over certain independent trees of elements. Zilber’s work on finite axiomatizability of totally categorical first order theories led to the development of geometric stability theory. We discuss some of the many applications of stability theory to algebraic geometry (focusing on the role of infinitary logic). And we conclude by noting the connections with non-commutative geometry. This paper is a kind of Whig history- tying into a (I hope) coherent and apparently forward moving narrative what were in fact a number of independent and sometimes conflicting themes. This paper developed from talk at the Boris-fest in 2010. But I have tried here to show how the ideas of Shelah and Zilber complement each other in the development of model theory. Their analysis led to frameworks which generalize first order logic in several ways. First they are led to consider more powerful logics and then to more ‘mathematical’ investigations of classes of structures satisfying appropriate properties. We refer to [Bal09] for expositions of many of the results; that’s why that book was written. It contains full historical references. -

Notes on Mathematical Logic David W. Kueker

Notes on Mathematical Logic David W. Kueker University of Maryland, College Park E-mail address: [email protected] URL: http://www-users.math.umd.edu/~dwk/ Contents Chapter 0. Introduction: What Is Logic? 1 Part 1. Elementary Logic 5 Chapter 1. Sentential Logic 7 0. Introduction 7 1. Sentences of Sentential Logic 8 2. Truth Assignments 11 3. Logical Consequence 13 4. Compactness 17 5. Formal Deductions 19 6. Exercises 20 20 Chapter 2. First-Order Logic 23 0. Introduction 23 1. Formulas of First Order Logic 24 2. Structures for First Order Logic 28 3. Logical Consequence and Validity 33 4. Formal Deductions 37 5. Theories and Their Models 42 6. Exercises 46 46 Chapter 3. The Completeness Theorem 49 0. Introduction 49 1. Henkin Sets and Their Models 49 2. Constructing Henkin Sets 52 3. Consequences of the Completeness Theorem 54 4. Completeness Categoricity, Quantifier Elimination 57 5. Exercises 58 58 Part 2. Model Theory 59 Chapter 4. Some Methods in Model Theory 61 0. Introduction 61 1. Realizing and Omitting Types 61 2. Elementary Extensions and Chains 66 3. The Back-and-Forth Method 69 i ii CONTENTS 4. Exercises 71 71 Chapter 5. Countable Models of Complete Theories 73 0. Introduction 73 1. Prime Models 73 2. Universal and Saturated Models 75 3. Theories with Just Finitely Many Countable Models 77 4. Exercises 79 79 Chapter 6. Further Topics in Model Theory 81 0. Introduction 81 1. Interpolation and Definability 81 2. Saturated Models 84 3. Skolem Functions and Indescernables 87 4. Some Applications 91 5. -

Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem for Mathematicians

G¨odel'sIncompleteness Theorem for Mathematicians Burak Kaya METU [email protected] November 23, 2016 Burak Kaya (METU) METU Math Club Student Seminars November 23, 2016 1 / 21 Hilbert wanted to formalize all mathematics in an axiomatic system which is consistent, i.e. no contradiction can be obtained from the axioms. complete, i.e. every true statement can be proved from the axioms. decidable, i.e. given a mathematical statement, there should be a procedure for deciding its truth or falsity. In 1931, Kurt G¨odelproved his famous incompleteness theorems and showed that Hilbert's program cannot be achieved. In 1936, Alan Turing proved that Hilbert's Entscheindungsproblem cannot be solved, i.e. there is no general algorithm which will decide whether a given mathematical statement is provable (from a given set of axioms.) Hilbert's program In 1920's, David Hilbert proposed a research program in the foundations of mathematics to provide secure foundations to mathematics and to eliminate the paradoxes and inconsistencies discovered by then. Burak Kaya (METU) METU Math Club Student Seminars November 23, 2016 2 / 21 consistent, i.e. no contradiction can be obtained from the axioms. complete, i.e. every true statement can be proved from the axioms. decidable, i.e. given a mathematical statement, there should be a procedure for deciding its truth or falsity. In 1931, Kurt G¨odelproved his famous incompleteness theorems and showed that Hilbert's program cannot be achieved. In 1936, Alan Turing proved that Hilbert's Entscheindungsproblem cannot be solved, i.e. there is no general algorithm which will decide whether a given mathematical statement is provable (from a given set of axioms.) Hilbert's program In 1920's, David Hilbert proposed a research program in the foundations of mathematics to provide secure foundations to mathematics and to eliminate the paradoxes and inconsistencies discovered by then. -

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu Richard Zach Calixto Badesa The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu (University of California, Berkeley) Richard Zach (University of Calgary) Calixto Badesa (Universitat de Barcelona) Final Draft—May 2004 To appear in: Leila Haaparanta, ed., The Development of Modern Logic. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 Contents Contents i Introduction 1 1 Itinerary I: Metatheoretical Properties of Axiomatic Systems 3 1.1 Introduction . 3 1.2 Peano’s school on the logical structure of theories . 4 1.3 Hilbert on axiomatization . 8 1.4 Completeness and categoricity in the work of Veblen and Huntington . 10 1.5 Truth in a structure . 12 2 Itinerary II: Bertrand Russell’s Mathematical Logic 15 2.1 From the Paris congress to the Principles of Mathematics 1900–1903 . 15 2.2 Russell and Poincar´e on predicativity . 19 2.3 On Denoting . 21 2.4 Russell’s ramified type theory . 22 2.5 The logic of Principia ......................... 25 2.6 Further developments . 26 3 Itinerary III: Zermelo’s Axiomatization of Set Theory and Re- lated Foundational Issues 29 3.1 The debate on the axiom of choice . 29 3.2 Zermelo’s axiomatization of set theory . 32 3.3 The discussion on the notion of “definit” . 35 3.4 Metatheoretical studies of Zermelo’s axiomatization . 38 4 Itinerary IV: The Theory of Relatives and Lowenheim’s¨ Theorem 41 4.1 Theory of relatives and model theory . 41 4.2 The logic of relatives . -

An Introduction to Ramsey Theory Fast Functions, Infinity, and Metamathematics

STUDENT MATHEMATICAL LIBRARY Volume 87 An Introduction to Ramsey Theory Fast Functions, Infinity, and Metamathematics Matthew Katz Jan Reimann Mathematics Advanced Study Semesters 10.1090/stml/087 An Introduction to Ramsey Theory STUDENT MATHEMATICAL LIBRARY Volume 87 An Introduction to Ramsey Theory Fast Functions, Infinity, and Metamathematics Matthew Katz Jan Reimann Mathematics Advanced Study Semesters Editorial Board Satyan L. Devadoss John Stillwell (Chair) Rosa Orellana Serge Tabachnikov 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 05D10, 03-01, 03E10, 03B10, 03B25, 03D20, 03H15. Jan Reimann was partially supported by NSF Grant DMS-1201263. For additional information and updates on this book, visit www.ams.org/bookpages/stml-87 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Katz, Matthew, 1986– author. | Reimann, Jan, 1971– author. | Pennsylvania State University. Mathematics Advanced Study Semesters. Title: An introduction to Ramsey theory: Fast functions, infinity, and metamathemat- ics / Matthew Katz, Jan Reimann. Description: Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, [2018] | Series: Student mathematical library; 87 | “Mathematics Advanced Study Semesters.” | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018024651 | ISBN 9781470442903 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Ramsey theory. | Combinatorial analysis. | AMS: Combinatorics – Extremal combinatorics – Ramsey theory. msc | Mathematical logic and foundations – Instructional exposition (textbooks, tutorial papers, etc.). msc | Mathematical -

Fundamental Theorems in Mathematics

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS IN MATHEMATICS OLIVER KNILL Abstract. An expository hitchhikers guide to some theorems in mathematics. Criteria for the current list of 243 theorems are whether the result can be formulated elegantly, whether it is beautiful or useful and whether it could serve as a guide [6] without leading to panic. The order is not a ranking but ordered along a time-line when things were writ- ten down. Since [556] stated “a mathematical theorem only becomes beautiful if presented as a crown jewel within a context" we try sometimes to give some context. Of course, any such list of theorems is a matter of personal preferences, taste and limitations. The num- ber of theorems is arbitrary, the initial obvious goal was 42 but that number got eventually surpassed as it is hard to stop, once started. As a compensation, there are 42 “tweetable" theorems with included proofs. More comments on the choice of the theorems is included in an epilogue. For literature on general mathematics, see [193, 189, 29, 235, 254, 619, 412, 138], for history [217, 625, 376, 73, 46, 208, 379, 365, 690, 113, 618, 79, 259, 341], for popular, beautiful or elegant things [12, 529, 201, 182, 17, 672, 673, 44, 204, 190, 245, 446, 616, 303, 201, 2, 127, 146, 128, 502, 261, 172]. For comprehensive overviews in large parts of math- ematics, [74, 165, 166, 51, 593] or predictions on developments [47]. For reflections about mathematics in general [145, 455, 45, 306, 439, 99, 561]. Encyclopedic source examples are [188, 705, 670, 102, 192, 152, 221, 191, 111, 635]. -

Model Completeness and Relative Decidability

Model Completeness and Relative Decidability Jennifer Chubb, Russell Miller,∗ & Reed Solomon March 5, 2019 Abstract We study the implications of model completeness of a theory for the effectiveness of presentations of models of that theory. It is im- mediate that for a computable model A of a computably enumerable, model complete theory, the entire elementary diagram E(A) must be decidable. We prove that indeed a c.e. theory T is model complete if and only if there is a uniform procedure that succeeds in deciding E(A) from the atomic diagram ∆(A) for all countable models A of T . Moreover, if every presentation of a single isomorphism type A has this property of relative decidability, then there must be a procedure with succeeds uniformly for all presentations of an expansion (A,~a) by finitely many new constants. We end with a conjecture about the situation when all models of a theory are relatively decidable. 1 Introduction The broad goal of computable model theory is to investigate the effective arXiv:1903.00734v1 [math.LO] 2 Mar 2019 aspects of model theory. Here we will carry out exactly this process with the model-theoretic concept of model completeness. This notion is well-known and has been widely studied in model theory, but to our knowledge there has never been any thorough examination of its implications for computability in structures with the domain ω. We now rectify this omission, and find natural and satisfactory equivalents for the basic notion of model completeness of a first-order theory. Our two principal results are each readily stated: that a ∗The second author was supported by NSF grant # DMS-1362206, Simons Foundation grant # 581896, and several PSC-CUNY research awards. -

More Model Theory Notes Miscellaneous Information, Loosely Organized

More Model Theory Notes Miscellaneous information, loosely organized. 1. Kinds of Models A countable homogeneous model M is one such that, for any partial elementary map f : A ! M with A ⊆ M finite, and any a 2 M, f extends to a partial elementary map A [ fag ! M. As a consequence, any partial elementary map to M is extendible to an automorphism of M. Atomic models (see below) are homogeneous. A prime model of T is one that elementarily embeds into every other model of T of the same cardinality. Any theory with fewer than continuum-many types has a prime model, and if a theory has a prime model, it is unique up to isomorphism. Prime models are homogeneous. On the other end, a model is universal if every other model of its size elementarily embeds into it. Recall a type is a set of formulas with the same tuple of free variables; generally to be called a type we require consistency. The type of an element or tuple from a model is all the formulas it satisfies. One might think of the type of an element as a sort of identity card for automorphisms: automorphisms of a model preserve types. A complete type is the analogue of a complete theory, one where every formula of the appropriate free variables or its negation appears. Types of elements and tuples are always complete. A type is principal if there is one formula in the type that implies all the rest; principal complete types are often called isolated. A trivial example of an isolated type is that generated by the formula x = c where c is any constant in the language, or x = t(¯c) where t is any composition of appropriate-arity functions andc ¯ is a tuple of constants. -

Set-Theoretic Foundations

Contemporary Mathematics Volume 690, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/conm/690/13872 Set-theoretic foundations Penelope Maddy Contents 1. Foundational uses of set theory 2. Foundational uses of category theory 3. The multiverse 4. Inconclusive conclusion References It’s more or less standard orthodoxy these days that set theory – ZFC, extended by large cardinals – provides a foundation for classical mathematics. Oddly enough, it’s less clear what ‘providing a foundation’ comes to. Still, there are those who argue strenuously that category theory would do this job better than set theory does, or even that set theory can’t do it at all, and that category theory can. There are also those who insist that set theory should be understood, not as the study of a single universe, V, purportedly described by ZFC + LCs, but as the study of a so-called ‘multiverse’ of set-theoretic universes – while retaining its foundational role. I won’t pretend to sort out all these complex and contentious matters, but I do hope to compile a few relevant observations that might help bring illumination somewhat closer to hand. 1. Foundational uses of set theory The most common characterization of set theory’s foundational role, the char- acterization found in textbooks, is illustrated in the opening sentences of Kunen’s classic book on forcing: Set theory is the foundation of mathematics. All mathematical concepts are defined in terms of the primitive notions of set and membership. In axiomatic set theory we formulate . axioms 2010 Mathematics Subject Classification. Primary 03A05; Secondary 00A30, 03Exx, 03B30, 18A15.