Agorapicbk-22.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Athenian Agora : Museum Guide / by Laura Gawlinski ; with Photographs by Craig A

The Athenian Agora Agora Athenian The Museum Guide Above: Inside the main gallery of the Athenian Agora Museum. Front cover: Poppies in the Athenian Agora front the reconstructed Stoa of Attalos which houses the Agora Museum. Photos: C. A. Mauzy Written for the general visitor, the Athenian Agora Museum Guide is a companion to the 2010 edition of the Athenian Agora Site Guide and leads the reader through the display spaces within the Agora’s Stoa of Attalos—the terrace, the ground-floor colonnade, and the newly opened upper story. The guide discusses each case in the museum gallery chronologically, beginning with the prehistoric Gawlinski and continuing with the Geometric, Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine periods. Hundreds of artifacts, ranging from ©2014 American School of Classical Studies at Athens Museum Guide common pottery to elite jewelry, are described and illustrated in color for the first time. Through brief fifth EDItION essays, readers can learn about marble- working, early burial practices, pottery Laura Gawlinski production, ostracism, home life, and the wells that dotted the ancient site. A time- ASCSA with photographs by line and maps accompany the text. Craig A. Mauzy Museum Guide ©2014 American School of Classical Studies at Athens ©2014 American School of Classical Studies at Athens The american school of classical studies at athens PRINCETON, New Jersey Museum Guide fifth EDItION Laura Gawlinski with photographs by Craig A. Mauzy ©2014 American School of Classical Studies at Athens The american school of classical studies at athens PRINCETON, New Jersey Copyright 2014. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens. -

Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC

Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 81, 2015, pp. 361–392 © The Prehistoric Society doi:10.1017/ppr.2015.17 Connected Histories: the Dynamics of Bronze Age Interaction and Trade 1500–1100 BC By KRISTIAN KRISTIANSEN1 and PAULINA SUCHOWSKA-DUCKE2 The Bronze Age was the first epoch in which societies became irreversibly linked in their co-dependence on ores and metallurgical skills that were unevenly distributed in geographical space. Access to these critical resources was secured not only via long-distance physical trade routes, making use of landscape features such as river networks, as well as built roads, but also by creating immaterial social networks, consisting of interpersonal relations and diplomatic alliances, established and maintained through the exchange of extraordinary objects (gifts). In this article, we reason about Bronze Age communication networks and apply the results of use-wear analysis to create robust indicators of the rise and fall of political and commercial networks. In conclusion, we discuss some of the historical forces behind the phenomena and processes observable in the archaeological record of the Bronze Age in Europe and beyond. Keywords: Bronze Age communication networks, agents, temperate Europe, Mediterranean Basin THE EUROPEAN BRONZE AGE AS A COMMUNICATION by small variations in ornaments and weapons NETWORK: HISTORICAL & THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK (Kristiansen 2014). Among the characteristics that might compel archaeo- Initially driven by the necessity to gain access to logists to label the Bronze Age a ‘formative epoch’ in remote resources and technological skills, Bronze Age European history, the density and extent of the era’s societies established communication links that ranged exchange and communication networks should per- from the Baltic to the Mediterranean and from haps be regarded as the most significant. -

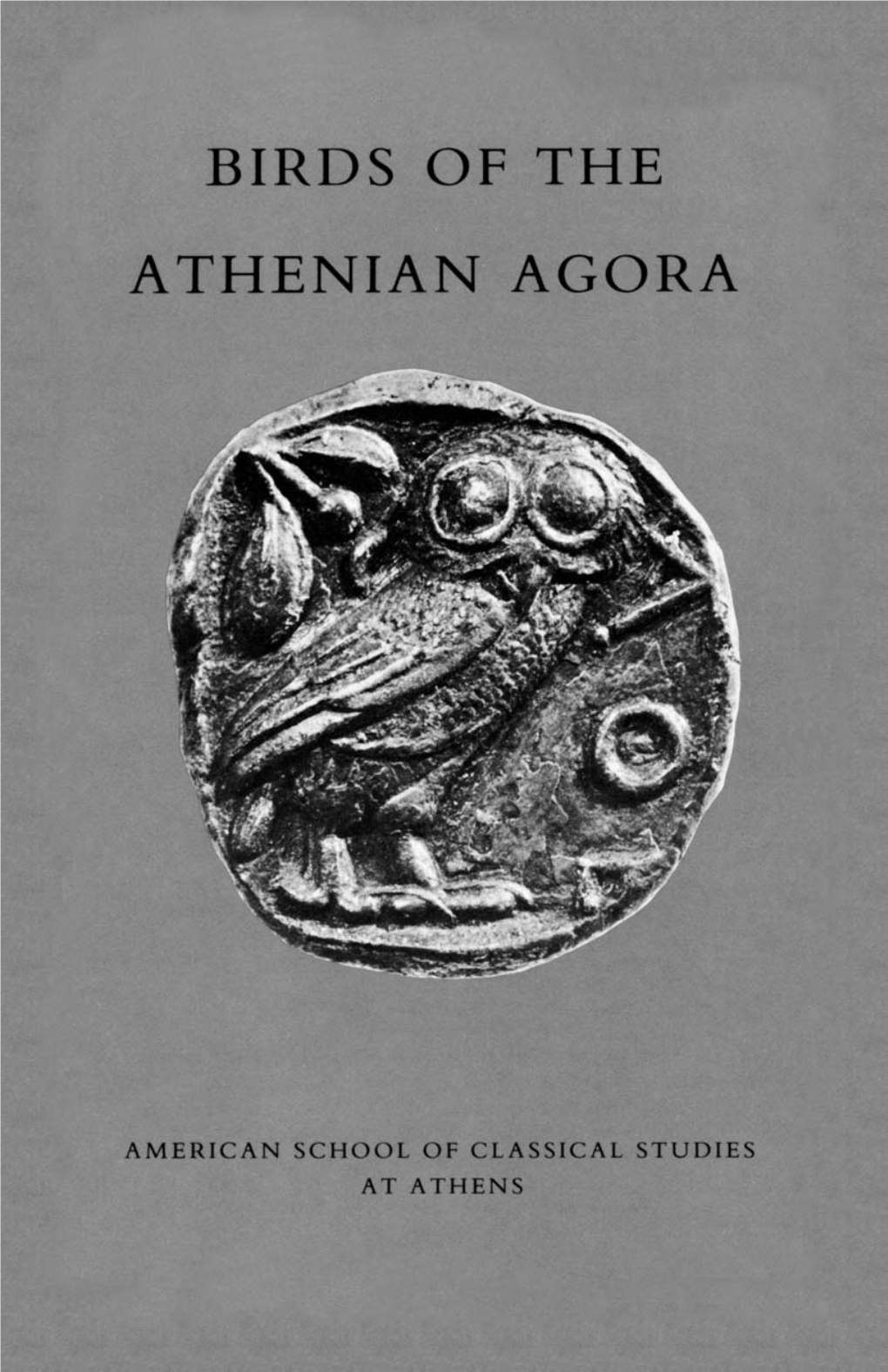

The Athenian Agora

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 12 Prepared by Dorothy Burr Thompson Produced by The Stinehour Press, Lunenburg, Vermont American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1993 ISBN 87661-635-x EXCAVATIONS OF THE ATHENIAN AGORA PICTURE BOOKS I. Pots and Pans of Classical Athens (1959) 2. The Stoa ofAttalos II in Athens (revised 1992) 3. Miniature Sculpturefrom the Athenian Agora (1959) 4. The Athenian Citizen (revised 1987) 5. Ancient Portraitsfrom the Athenian Agora (1963) 6. Amphoras and the Ancient Wine Trade (revised 1979) 7. The Middle Ages in the Athenian Agora (1961) 8. Garden Lore of Ancient Athens (1963) 9. Lampsfrom the Athenian Agora (1964) 10. Inscriptionsfrom the Athenian Agora (1966) I I. Waterworks in the Athenian Agora (1968) 12. An Ancient Shopping Center: The Athenian Agora (revised 1993) I 3. Early Burialsfrom the Agora Cemeteries (I 973) 14. Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (revised 1988) I 5. Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora (1975) 16. The Athenian Agora: A Short Guide (revised 1986) French, German, and Greek editions 17. Socrates in the Agora (1978) 18. Mediaeval and Modern Coins in the Athenian Agora (1978) 19. Gods and Heroes in the Athenian Agora (1980) 20. Bronzeworkers in the Athenian Agora (1982) 21. Ancient Athenian Building Methods (1984) 22. Birds ofthe Athenian Agora (1985) These booklets are obtainable from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens c/o Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J. 08540, U.S.A They are also available in the Agora Museum, Stoa of Attalos, Athens Cover: Slaves carrying a Spitted Cake from Market. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Stoa Poikile) Built About 475-450 BC

Arrangement Classical Greek cities – either result of continuous growth, or created at a single moment. Former – had streets –lines of communication, curving, bending- ease gradients. Later- had grid plans – straight streets crossing at right angles- ignoring obstacles became stairways where gradients were too steep. Despite these differences, certain features and principles of arrangement are common to both. Greek towns Towns had fixed boundaries. In 6th century BC some were surrounded by fortifications, later became more frequent., but even where there were no walls - demarcation of interior and exterior was clear. In most Greek towns availability of area- devoted to public use rather than private use. Agora- important gathering place – conveniently placed for communication and easily accessible from all directions. The Agora Of Athens • Agora originally meant "gathering place" but came to mean the market place and public square in an ancient Greek city. It was the political, civic, and commercial center of the city, near which were stoas, temples, administrative & public buildings, market places, monuments, shrines etc. • The agora in Athens had private housing, until it was reorganized by Peisistratus in the 6th century BC. • Although he may have lived on the agora himself, he removed the other houses, closed wells, and made it the centre of Athenian government. • He also built a drainage system, fountains and a temple to the Olympian gods. • Cimon later improved the agora by constructing new buildings and planting trees. • In the 5th century BC there were temples constructed to Hephaestus, Zeus and Apollo. • The Areopagus and the assembly of all citizens met elsewhere in Athens, but some public meetings, such as those to discuss ostracism, were held in the agora. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

PLATE I . Jug of the 15Th Century B.C. from Kourion UNIVERSITY MUSEUM BULLETIN VOL

• PLATE I . Jug of the 15th Century B.C. from Kourion UNIVERSITY MUSEUM BULLETIN VOL . 8 JANUARY. 1940 N o. l THE ACHAEANS AT KOURION T HE University Museum has played a distinguished part in the redis- covery of the pre-Hellenic civilization of Greece. The Heroic Age de- scribed by Homer was first shown to have a basis in fact by Schliemann's excavations at Troy in 1871, and somewhat later at Mycenae and Tiryns, and by Evans' discovery of the palace of King Minos at Knossos in Crete. When the first wild enthusiasm blew itself out it became apparent that many problems raised by this newly discovered civilization were not solved by the first spectacular finds. In the period of careful excavation and sober consideration of evidence which followed, the University Mu- seum had an important part. Its expeditions to various East Cretan sites did much lo put Cretan archaeology on the firm foundation it now enjoys. Alter the excavations at Vrokastro in East Crete in 1912 the efforts of the Museum were directed to other lands. It was only in 1931, when an e xpedition under the direction of Dr. B. H. Hill excavated at Lapithos in Cyprus, that the University Museum re-entered the early Greek field. The Cyprus expedition was recompcsed in 1934, still under the direc- tion of Dr. Hill, with the assistance of Mr. George H. McFadden and the writer, and began work at its present site, ancient Kourion. Kourion was 3 in classical times lhe capital of cne of the independent kingdoms of Cyprus, and was traditionally Greek. -

Ciarán Lavelle 2010

THE ZIBBY GARNETT TRAVELLING FELLOWSHIP Report by Ciarán Lavelle Archaeological Conservation Agora Excavations, Athens, Greece 12 June - August 2010 Page | 1 Contents Page No…... 1. Introduction……………………………......................................................................3 2. The American School of Classical Studies at Athens………………………………4 3. The Athenian Agora………………………………………………………………….4 4. The Athenian Agora Excavations……....…………………………………………...6 5. The Agora Conservation Team & Conservation Laboratory………………...…...8 6. My work on the Conservation Team.……………………………………………...12 7. On-site Conservation…………………………………………………………….…18 8. Conservation Teaching & Workshops………………………………………….…19 9. Sightseeing in Greece…………………………………………………………….…20 10. Life in Greece…………………………………………………………………...…22 11. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….23 Page | 2 1. Introduction My name is Ciaran Lavelle; I am a 28 year old from Northern Ireland. I am a recent graduate of the ‘Conservation of Objects for Museums and Archaeology’ Bachelor of Science degree program at Cardiff University in Wales. My goal for my career is find employment in the field of object conservation in a museum or in the private sector and become an accredited conservator. I completed the three year conservation degree in Cardiff University in two years as a direct entry student, which allowed me to combine first and second year. During my first year at Cardiff I learned about the American School of Classical Studies at Athens conservation internship program through a fellow Greek student. So during my final year I decided I should apply for the internship so as to gain post graduate experience in a world renowned archaeological excavation and was successful with my application for the nine week program. I heard about the Zibby Garnett Travelling Fellowship through a past recipient of the fund whom I worked with and became friends with while working in the Transport Museum in Glasgow. -

"A Collaborative Study of Early Glassmaking in Egypt C. 1500 BC." Annales Du 13E Congrès De L’Association Internationale Pour L’Histoire Du Verre

Lilyquist, C.; Brill, R. H. "A Collaborative Study of Early Glassmaking in Egypt c. 1500 BC." Annales du 13e Congrès de l’Association Internationale pour l’Histoire du Verre. Lochem, the Netherlands: AIHV, 1996, pp. 1-9. © 1996, Lochem AIHV. Used with permission. A collaborative study of early glassmaking in Egypt c. 1500 BC C. Lilyquist and R. H. Brill Our study of early glass was begun when we discovered that Metropolitan Museum objects from the tomb of three foreign wives of Tuthmosis I11 in the Wadi Qirud at Luxor had many more vitreous items than had been thought during the last 60 years. Not only was there a glass lotiform vessel (fig. 34)', but two glassy vessels (fig. lo), and many beads and a great amount of inlay of glass (figs. 36-40). As it became apparent that half of the inlays had been colored by cobalt (that rare metal whose provenance in the 2nd millennium BC is still a mystery), and when the primary author realized that most of the Egyptian glass studies published up to then had used 14th113th century BC or poorly dated samples, rather than 15th cen- tury BC or earlier glass, a collaborative project was begun at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Corning Museum of Glass. The first goal was to build a corpus of early dated glasses, compositionally analyzed. As we proceeded, we therefore-decided to explore glassy materials contempo- rary with, or earlier than, our "pre-Malkata Palace" glasses as we called them (i.e., pre-1400 BC; figs. 1, 3-5,7-9). -

The "Agora" of Pausanias I, 17, 1-2

THE "AGORA" OF PAUSANIAS I, 17, 1-2 P AUSANIAS has given us a long description of the main square of ancient Athens, a place which we are accustomed to call the Agora following Classical Greek usage but which he calls the Kerameikos according to the usage of his own time. This name Kerameikos he uses no less than five times, and in each case it is clear that he is referringto the main square, the ClassicalAgora, of Athens. " There are stoas from the gates to the Kerameikos" he says on entering the city (I, 2, 4), and then, as he begins his description of the square, " the place called Kerameikoshas its name from the hero Keramos-first on the right is the Stoa Basileios as it is called " (I, 3, 1). Farther on he says " above the Kerameikosand the stoa called Basileios is the temple of Hephaistos " (I, 14, 6). Describing Sulla's captureof Athens in 86 B.C. he says that the Roman general shut all the Athenians who had opposed him into the Kerameikos and had one out of each ten of them killed (I, 20, 6). It is generally agreed that this refers to the Classical Agora. Finally, when visiting Mantineia in far-off Arcadia (VII, 9, 8) Pausanias reports seeing ".a copy of the painting in the Kerameikos showing the deeds of the Athenians at Mantineia." The original painting in Athens was in the Stoa of Zeus on the main square, and Pausanias had already described it in his account of Athens (I, 3, 4). -

Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens Grizelda Mcclelland Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Summer 8-26-2013 Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens Grizelda McClelland Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation McClelland, Grizelda, "Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1150. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Classics Department of Art History and Archaeology Dissertation Examination Committee: Susan I. Rotroff, Chair Wendy Love Anderson William Bubelis Robert D. Lamberton George Pepe Sarantis Symeonoglou Constructions of Childhood on the Funerary Monuments of Roman Athens by Grizelda D. McClelland A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © 2013, Grizelda Dunn McClelland Table of Contents Figures ............................................................................................................................... -

Pre-Publication Proof

Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface xi List of Contributors xiii proof Introduction: Long-Distance Communication and the Cohesion of Early Empires 1 K a r e n R a d n e r 1 Egyptian State Correspondence of the New Kingdom: T e Letters of the Levantine Client Kings in the Amarna Correspondence and Contemporary Evidence 10 Jana Myná r ̌ová Pre-publication 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World 3 2 Mark Weeden 3 An Imperial Communication Network: T e State Correspondence of the Neo-Assyrian Empire 64 K a r e n R a d n e r 4 T e Lost State Correspondence of the Babylonian Empire as Ref ected in Contemporary Administrative Letters 94 Michael Jursa 5 State Communications in the Persian Empire 112 Amé lie Kuhrt Book 1.indb v 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM vi Contents 6 T e King’s Words: Hellenistic Royal Letters in Inscriptions 141 Alice Bencivenni 7 State Correspondence in the Roman Empire: Imperial Communication from Augustus to Justinian 172 Simon Corcoran Notes 211 Bibliography 257 Index 299 proof Pre-publication Book 1.indb vi 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM Chapter 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World M a r k W e e d e n T HIS chapter describes and discusses the evidence 1 for the internal correspondence of the Hittite state during its so-called imperial period (c. 1450– 1200 BC). Af er a brief sketch of the geographical and historical background, we will survey the available corpus and the generally well-documented archaeologi- cal contexts—a rarity among the corpora discussed in this volume.