Which Way to the Brain? a Parasite's Favorite Entry Portals Into Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes

diversity Article A Global Assessment of Parasite Diversity in Galaxiid Fishes Rachel A. Paterson 1,*, Gustavo P. Viozzi 2, Carlos A. Rauque 2, Verónica R. Flores 2 and Robert Poulin 3 1 The Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, P.O. Box 5685, Torgarden, 7485 Trondheim, Norway 2 Laboratorio de Parasitología, INIBIOMA, CONICET—Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Quintral 1250, San Carlos de Bariloche 8400, Argentina; [email protected] (G.P.V.); [email protected] (C.A.R.); veronicaroxanafl[email protected] (V.R.F.) 3 Department of Zoology, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +47-481-37-867 Abstract: Free-living species often receive greater conservation attention than the parasites they support, with parasite conservation often being hindered by a lack of parasite biodiversity knowl- edge. This study aimed to determine the current state of knowledge regarding parasites of the Southern Hemisphere freshwater fish family Galaxiidae, in order to identify knowledge gaps to focus future research attention. Specifically, we assessed how galaxiid–parasite knowledge differs among geographic regions in relation to research effort (i.e., number of studies or fish individuals examined, extent of tissue examination, taxonomic resolution), in addition to ecological traits known to influ- ence parasite richness. To date, ~50% of galaxiid species have been examined for parasites, though the majority of studies have focused on single parasite taxa rather than assessing the full diversity of macro- and microparasites. The highest number of parasites were observed from Argentinean galaxiids, and studies in all geographic regions were biased towards the highly abundant and most widely distributed galaxiid species, Galaxias maculatus. -

RUNNING HEAD: Farrow-Aspects of the Life Cycle of Apharyngostrigea Pipientis

RUNNING HEAD: Farrow-Aspects of the life cycle of Apharyngostrigea pipientis Aspects of the life cycle of Apharyngostrigea pipientis in Central Florida wetlands Abigail Farrow Florida Southern College RUNNING HEAD: Farrow-Aspects of the life cycle of Apharyngostrigea pipientis Abstract Apharyngostrigea pipientis (Trematoda: Strigeidae) is known to form metacercariae around the pericardium of anuran tadpoles in Michigan and other northern locations. Definitive hosts are thought to be wading birds, while the intermediate host is a freshwater snail. Apharyngostrigea pipientis is not commonly reported from Florida, yet we have found several populations of snails (Biopholaria havaensis) and tadpoles, primarily the Cuban treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis), to host this trematode. We used experimental infections to elucidate the transmission dynamics and development of A. pipientis inside the tadpole host. Surprisingly, we found two types (species?) of cercariae being shed from B. havaensis that enter Cuban treefrog tadpoles to form seemingly identical metacercariae. Further, both of these develop into metaceracariae inside the tadpoles over 5-7 days after wondering inside the host's body cavity as mesocercariae, and metacercariae are commonly concentrated around the pericardium cavity. However, they differ in entry mode, with one being ingested, whereas the other penetrates the skin. This project is ongoing. 1. Introduction The study of parasitology plays a vital role in understanding the foundation of communities in different ecosystems. Parasites have the ability to exploit their hosts, directly affecting the health of the organism and the environment. By having these abilities, it could mean a change in the way the organism contributes to and balances the overall ecosystem (Poulin, 1999). -

(Trematoda; Cestoda; Nematoda) Geographic Records from Three Species of Owls (Strigiformes) in Southeastern Oklahoma Chris T

92 New Ectoparasite (Diptera; Phthiraptera) and Helminth (Trematoda; Cestoda; Nematoda) Geographic Records from Three Species of Owls (Strigiformes) in Southeastern Oklahoma Chris T. McAllister Science and Mathematics Division, Eastern Oklahoma State College, Idabel, OK 74745 John M. Kinsella HelmWest Laboratory, 2108 Hilda Avenue, Missoula, MT 59801 Lance A. Durden Department of Biology, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA 30458 Will K. Reeves Colorado State University, C. P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Fort Collins, CO 80521 Abstract: We are just now beginning to learn about the ectoparasites and helminth parasites of some owls of Oklahoma. Some recent contributions from our lab have attempted to help fill a previous void in that information. Here, we report, four taxa of ectoparasites and five helminth parasites from three species of owls in Oklahoma. They include two species of chewing lice (Strigiphilus syrnii and Kurodeia magna), two species of hippoboscid flies (Icosta americana and Ornithoica vicina), a trematode (Strigea elegans) and a cestode (Paruterina candelabraria) from barred owls (Strix varia), and three nematodes, Porrocaecum depressum from an eastern screech owl (Megascops asio), Capillaria sp. eggs from S. varia, and Capillaria tenuissima from a great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). With the exception of Capillaria sp. eggs and I. americana, all represent new state records for Oklahoma and extend our knowledge of the parasitic biota of owls of the state. to opportunistically examine raptors from the Introduction state and document new geographic records for their parasites in Oklahoma. Over 455 species of birds have been reported Methods from Oklahoma and several are species of raptors or birds of prey that make up an important Between January 2018 and September 2019, portion of the avian fauna of the state (Sutton three owls were found dead on the road in 1967; Baumgartner and Baumgartner 1992). -

Parasitology Volume 60 60

Advances in Parasitology Volume 60 60 Cover illustration: Echinobothrium elegans from the blue-spotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma) in Australia, a 'classical' hypothesis of tapeworm evolution proposed 2005 by Prof. Emeritus L. Euzet in 1959, and the molecular sequence data that now represent the basis of contemporary phylogenetic investigation. The emergence of molecular systematics at the end of the twentieth century provided a new class of data with which to revisit hypotheses based on interpretations of morphology and life ADVANCES IN history. The result has been a mixture of corroboration, upheaval and considerable insight into the correspondence between genetic divergence and taxonomic circumscription. PARASITOLOGY ADVANCES IN ADVANCES Complete list of Contents: Sulfur-Containing Amino Acid Metabolism in Parasitic Protozoa T. Nozaki, V. Ali and M. Tokoro The Use and Implications of Ribosomal DNA Sequencing for the Discrimination of Digenean Species M. J. Nolan and T. H. Cribb Advances and Trends in the Molecular Systematics of the Parasitic Platyhelminthes P P. D. Olson and V. V. Tkach ARASITOLOGY Wolbachia Bacterial Endosymbionts of Filarial Nematodes M. J. Taylor, C. Bandi and A. Hoerauf The Biology of Avian Eimeria with an Emphasis on Their Control by Vaccination M. W. Shirley, A. L. Smith and F. M. Tomley 60 Edited by elsevier.com J.R. BAKER R. MULLER D. ROLLINSON Advances and Trends in the Molecular Systematics of the Parasitic Platyhelminthes Peter D. Olson1 and Vasyl V. Tkach2 1Division of Parasitology, Department of Zoology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK 2Department of Biology, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, 58202-9019, USA Abstract ...................................166 1. -

Phylogenetic Studies of Larval Digenean Trematodes from Freshwater Snails and Fish Species in the Proximity of Tshwane Metropolitan, South Africa

Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research ISSN: (Online) 2219-0635, (Print) 0030-2465 Page 1 of 7 Original Research Phylogenetic studies of larval digenean trematodes from freshwater snails and fish species in the proximity of Tshwane metropolitan, South Africa Authors: The classification and description of digenean trematodes are commonly accomplished by 1 Esmey B. Moema using morphological features, especially in adult stages. The aim of this study was to provide Pieter H. King1 Johnny N. Rakgole2 an analysis of the genetic composition of larval digenean trematodes using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and sequence analysis. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was extracted Affiliations: from clinostomatid metacercaria, 27-spined echinostomatid redia, avian schistosome cercaria 1 Department of Biology, and strigeid metacercaria from various dams in the proximity of Tshwane metropolitan, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa. Polymerase chain reaction was performed using the extracted DNA with South Africa primers targeting various regions within the larval digenean trematodes’ genomes. Agarose gel electrophoresis technique was used to visualise the PCR products. The PCR products 2Department of Virology, were sequenced on an Applied Bioinformatics (ABI) genetic analyser platform. Genetic Sefako Makgatho Health information obtained from this study had a higher degree of discrimination than the Sciences University, Pretoria, South Africa morphological characteristics of seemingly similar organisms. Corresponding author: Keywords: digenean trematodes; classification; description; polymerase chain reaction; PCR; Esmey Moema, genetic composition; sequence analysis; nucleotide variations; molecular analysis. [email protected] Dates: Received: 09 Jan. 2019 Introduction Accepted: 18 Apr. 2019 The classification of digenean parasites, especially using only the larval stages, to determine the Published: 17 Sept. -

Climate Change and Freshwater Fisheries

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282814011 Climate change and freshwater fisheries Chapter · September 2015 DOI: 10.1002/9781118394380.ch50 CITATIONS READS 15 1,011 1 author: Chris Harrod University of Antofagasta 203 PUBLICATIONS 2,695 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: "Characterizing the Ecological Niche of Native Cockroaches in a Chilean biodiversity hotspot: diet and plant-insect associations" National Geographic Research and Exploration GRANT #WW-061R-17 View project Effects of seasonal and monthly hypoxic oscillations on seabed biota: evaluating relationships between taxonomical and functional diversity and changes on trophic structure of macrobenthic assemblages View project All content following this page was uploaded by Chris Harrod on 28 February 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Chapter 7.3 Climate change and freshwater fisheries Chris Harrod Instituto de Ciencias Naturales Alexander Von Humboldt, Universidad de Antofagasta, Antofagasta, Chile Abstract: Climate change is among the most serious environmental challenge facing humanity and the ecosystems that provide the goods and services on which it relies. Climate change has had a major historical influence on global biodiversity and will continue to impact the structure and function of natural ecosystems, including the provision of natural services such as fisheries. Freshwater fishery professionals (e.g. fishery managers, fish biologists, fishery scientists and fishers) need to be informed regarding the likely impacts of climate change. Written for such an audience, this chapter reviews the drivers of climatic change and the means by which its impacts are predicted. -

Leeches As the Intermediate Host for Strigeid Trematodes: Genetic

Pyrka et al. Parasites Vectors (2021) 14:44 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04538-9 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access Leeches as the intermediate host for strigeid trematodes: genetic diversity and taxonomy of the genera Australapatemon Sudarikov, 1959 and Cotylurus Szidat, 1928 Ewa Pyrka1, Gerard Kanarek2* , Grzegorz Zaleśny3 and Joanna Hildebrand1 Abstract Background: Leeches (Hirudinida) play a signifcant role as intermediate hosts in the circulation of trematodes in the aquatic environment. However, species richness and the molecular diversity and phylogeny of larval stages of strigeid trematodes (tetracotyle) occurring in this group of aquatic invertebrates remain poorly understood. Here, we report our use of recently obtained sequences of several molecular markers to analyse some aspects of the ecology, taxon- omy and phylogeny of the genera Australapatemon and Cotylurus, which utilise leeches as intermediate hosts. Methods: From April 2017 to September 2018, 153 leeches were collected from several sampling stations in small rivers with slow-fowing waters and related drainage canals located in three regions of Poland. The distinctive forms of tetracotyle metacercariae collected from leeches supplemented with adult Strigeidae specimens sampled from a wide range of water birds were analysed using the 28S rDNA partial gene, the second internal transcribed spacer region (ITS2) region and the cytochrome c oxidase (COI) fragment. Results: Among investigated leeches, metacercariae of the tetracotyle type were detected in the parenchyma and musculature of 62 specimens (prevalence 40.5%) with a mean intensity reaching 19.9 individuals. The taxonomic generic afliation of metacercariae derived from the leeches revealed the occurrence of two strigeid genera: Aus- tralapatemon Sudarikov, 1959 and Cotylurus Szidat, 1928. -

New Primers for DNA Barcoding of Digeneans and Cestodes (Platyhelminthes)

Molecular Ecology Resources (2015) 15, 945–952 doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12358 New primers for DNA barcoding of digeneans and cestodes (Platyhelminthes) NIELS VAN STEENKISTE,* SEAN A. LOCKE,†1 MAGALIE CASTELIN,* DAVID J. MARCOGLIESE† and CATHRYN L. ABBOTT* *Aquatic Animal Health Section, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Pacific Biological Station, 3190 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo, BC, Canada V9T 6N7, †Aquatic Biodiversity Section, Watershed Hydrology and Ecology Research Division, Water Science and Technology Directorate, Science and Technology Branch, Environment Canada, St. Lawrence Centre, 105 McGill, 7th Floor, Montreal, QC, Canada H2Y 2E7 Abstract Digeneans and cestodes are species-rich taxa and can seriously impact human health, fisheries, aqua- and agriculture, and wildlife conservation and management. DNA barcoding using the COI Folmer region could be applied for spe- cies detection and identification, but both ‘universal’ and taxon-specific COI primers fail to amplify in many flat- worm taxa. We found that high levels of nucleotide variation at priming sites made it unrealistic to design primers targeting all flatworms. We developed new degenerate primers that enabled acquisition of the COI barcode region from 100% of specimens tested (n = 46), representing 23 families of digeneans and 6 orders of cestodes. This high success rate represents an improvement over existing methods. Primers and methods provided here are critical pieces towards redressing the current paucity of COI barcodes for these taxa in public databases. Keywords: Cestoda, COI, Digenea, DNA barcoding, Platyhelminthes, Primers Received 18 February 2014; revision received 18 November 2014; accepted 21 November 2014 digeneans and eight cestodes; Hebert et al. 2003), it was Introduction soon recognized that primer modification would be Digenea (flukes) and Cestoda (tapeworms) are among needed for reliable amplification of the COI barcode in the most species-rich groups of parasitic metazoans. -

Fish Blood Flukes"

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2009 Historical Account of the Two Family-group Names in Use for the Single Accepted Family Comprising the "Fish Blood Flukes" Stephen A. Bullard Auburn University, [email protected] Kirsten Jensen University of Kansas Robin M. Overstreet Gulf Coast Research Laboratory, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Bullard, Stephen A.; Jensen, Kirsten; and Overstreet, Robin M., "Historical Account of the Two Family- group Names in Use for the Single Accepted Family Comprising the "Fish Blood Flukes"" (2009). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 433. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/433 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DOI: 10.2478/s11686-009-0012-8 © 2009 W. Stefañski Institute of Parasitology, PAS Acta Parasitologica, 2009, 54(1), 78–84; ISSN 1230-2821 Historical account of the two family-group names in use for the single accepted family comprising the “fish blood -

Falconiformes, Accipitriformes, Strigiformes) in the Slovak Republic

©2017 Institute of Parasitology, SAS, Košice DOI 10.1515/helm-2017-0038 HELMINTHOLOGIA, 54, 4: 314 – 321, 2017 New data on helminth fauna of birds of prey (Falconiformes, Accipitriformes, Strigiformes) in the Slovak Republic P. KOMOROVÁ1*, J. SITKO2, M. ŠPAKULOVÁ3, Z. HURNÍKOVÁ3,1, R. SAŁAMATIN4, 5, G. CHOVANCOVÁ6 1Department of Epizootology and Parasitology, Institute of Parasitology, The University of Veterinary Medicine and Pharmacy in Košice, Komenského 73, 041 81 Košice, Slovak Republic, *E-mail: [email protected]; 2Ornitological Station of Commenius Museum in Přerov, Bezručova 10, 750 02 Přerov, Czech Republic; 3Institute of Parasitology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Hlinkova 3, 040 01 Košice, Slovak Republic; 4Department of General Biology and Parasitology, Medical University of Warsaw, Chałubińskiego 5, 02-004 Warsaw, Poland; 5Department of Parasitology, National Institute of Public Health – National Institute of Hygiene, Chocimska 24, 00-719 Warsaw, Poland; 6Research Station and Museum of the Tatra National Park, 059 60 Tatranská Lomnica, Slovak Republic Article info Summary Received December 1, 2016 In the years 2012-2014, carcasses of 286 birds of prey from the territory of Slovakia were examined Accepted July 4, 2017 for the presence of helminth parasites. The number of bird species in the study was 23; fi ve belonging to the Falconiformes order, eleven to Accipitriformes, and seven to Strigiformes. A fi nding of Cestoda class comprehended 4 families: Paruterinidae (4), Dilepididae (2), Mesocestoididae (2) and Anoplo- cephalidae (1). Birds of prey were infected with 6 families Nematoda species of the Secernentea class: Syngamidae (1), Habronematidae (2), Tetrameridae (3), Physalopteridae (1), Acuariidae (1), and Anisakidae (2). -

Cardiocephaloides Longicollis (Rudolphi, 1819) Dubois, 1982 (Strigeidae) Into the Gilthead Seabream Sparus Aurata L

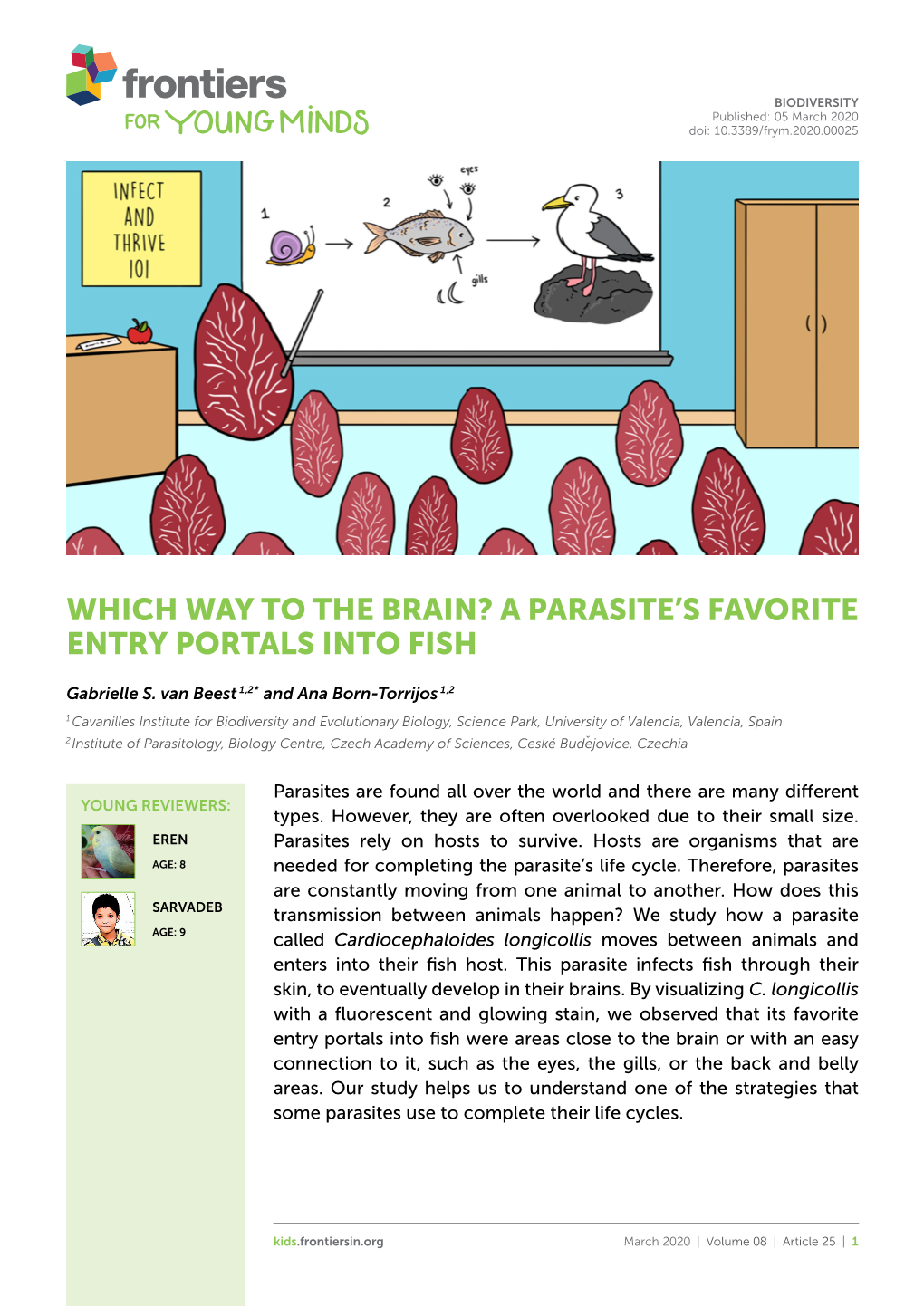

van Beest et al. Parasites Vectors (2019) 12:92 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3351-9 Parasites & Vectors RESEARCH Open Access In vivo fuorescent cercariae reveal the entry portals of Cardiocephaloides longicollis (Rudolphi, 1819) Dubois, 1982 (Strigeidae) into the gilthead seabream Sparus aurata L. Gabrielle S. van Beest1,2*, Mar Villar‑Torres1, Juan Antonio Raga1, Francisco Esteban Montero1 and Ana Born‑Torrijos1,2 Abstract Background: Despite their complex life‑cycles involving various types of hosts and free‑living stages, digenean trematodes are becoming recurrent model systems. The infection and penetration strategy of the larval stages, i.e. cer‑ cariae, into the fsh host is poorly understood and information regarding their entry portals is not well‑known for most species. Cardiocephaloides longicollis (Rudolphi, 1819) Dubois, 1982 (Digenea, Strigeidae) uses the gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata L.), an important marine fsh in Mediterranean aquaculture, as a second intermediate host, where they encyst in the brain as metacercariae. Labelling the cercariae with in vivo fuorescent dyes helped us to track their entry into the fsh, revealing the penetration pattern that C. longicollis uses to infect S. aurata. Methods: Two diferent fuorescent dyes were used: carboxyfuorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and Hoe‑ chst 33342 (NB). Three ascending concentrations of each dye were tested to detect any efect on labelled cercarial performance, by recording their survival for the frst 5 h post‑labelling (hpl) and 24 hpl, as well as their activity for 5 hpl. Labelled cercariae were used to track the penetration points into fsh, and cercarial infectivity and later encyst‑ ment were analysed by recording brain‑encysted metacercariae in fsh infected with labelled and control cercariae after 20 days of infection. -

Irish Biodiversity: a Taxonomic Inventory of Fauna

Irish Biodiversity: a taxonomic inventory of fauna Irish Wildlife Manual No. 38 Irish Biodiversity: a taxonomic inventory of fauna S. E. Ferriss, K. G. Smith, and T. P. Inskipp (editors) Citations: Ferriss, S. E., Smith K. G., & Inskipp T. P. (eds.) Irish Biodiversity: a taxonomic inventory of fauna. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 38. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Section author (2009) Section title . In: Ferriss, S. E., Smith K. G., & Inskipp T. P. (eds.) Irish Biodiversity: a taxonomic inventory of fauna. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 38. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photos: © Kevin G. Smith and Sarah E. Ferriss Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: N. Kingston and F. Marnell © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2009 ISSN 1393 - 6670 Inventory of Irish fauna ____________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary.............................................................................................................................................1 Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................3 Methodology........................................................................................................................................................................3