PDF for Tablets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and The

Awkward Objects: Relics, the Making of Religious Meaning, and the Limits of Control in the Information Age Jan W Geisbusch University College London Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Anthropology. 15 September 2008 UMI Number: U591518 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591518 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration of authorship: I, Jan W Geisbusch, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature: London, 15.09.2008 Acknowledgments A thesis involving several years of research will always be indebted to the input and advise of numerous people, not all of whom the author will be able to recall. However, my thanks must go, firstly, to my supervisor, Prof Michael Rowlands, who patiently and smoothly steered the thesis round a fair few cliffs, and, secondly, to my informants in Rome and on the Internet. Research was made possible by a grant from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). -

Vol.5-1:Layout 1.Qxd

Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Volume 1 Sowing the Seed, 1822-1840 Volume 2 Nurturing the Seedling, 1841-1848 Volume 3 Jolted and Joggled, 1849-1852 Volume 4 Vigorous Growth, 1853-1858 Volume 5 Living Branches, 1859-1867 Volume 6 Mission to North America, 1847-1859 Volume 7 Mission to North America, 1860-1879 Volume 8 Mission to Prussia: Brede Volume 9 Mission to Prussia: Breslau Volume 10 Mission to Upper Austria Volume 11 Mission to Baden Mission to Gorizia Volume 12 Mission to Hungary Volume 13 Mission to Austria Mission to England Volume 14 Mission to Tyrol Volume 15 Abundant Fruit, 1868-1879 Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger Foundress of the School Sisters of Notre Dame Volume 5 Living Branches 1859—1867 Translated, Edited, and Annotated by Mary Ann Kuttner, SSND School Sisters of Notre Dame Printing Department Elm Grove, Wisconsin 2009 Copyright © 2009 by School Sisters of Notre Dame Via della Stazione Aurelia 95 00165 Rome, Italy All rights reserved. Cover Design by Mary Caroline Jakubowski, SSND “All the works of God proceed slowly and in pain; but then, their roots are the sturdier and their flowering the lovelier.” Mary Theresa of Jesus Gerhardinger No. 2277 Contents Preface to Volume 5 ix Introduction xi Chapter 1 1859 1 Chapter 2 1860 39 Chapter 3 1861 69 Chapter 4 1862 93 Chapter 5 1863 121 Chapter 6 1864 129 Chapter 7 1865 147 Chapter 8 1866 175 Chapter 9 1867 201 List of Documents 223 Index 227 ix Preface to Volume 5 Volume 5 of Letters of Mary Theresa of Jesus Ger- hardinger includes documents from the years 1859 through 1867, a time of growth for the congregation in both Europe and North America. -

SC Masters Redesign.Qxd

May 25 to May 31, 2011 www.scross.co.za R5,50 (incl VaT RSa) Reg no. 1920/002058/06 no 4727 Record number Let’s ♥ our Vatican issues for Jo’burg’s priests and new norms Fatima procession missionaries for old Mass Page 3 Page 7 Page 4 Vatican’s new rules to handle abuse By Cindy wooden The special provisions issued in the past ten years expanded or extended several VERY bishops’ conference in the world points of Church law: they defined a minor must have guidelines for handling as a person under age 18 rather than 16; set Eaccusations of clerical sex abuse in a statute of limitations of 20 years, instead place within a year, the Congregation for of ten years, after the victim’s 18th birthday the Doctrine of the Faith said in new guide - for bringing a Church case against an lines. alleged perpetrator; established an abbrevi - The Church in the Southern African ated administrative procedure for removing region already has such protocols in place. guilty clerics from the priesthood; and A letter to all bishops’ conferences signed included child pornography among crimes by the congregation’s prefect, Cardinal which could bring expulsion from the William Levada, said that in every nation priesthood. and region, bishops should have “clear and Barbara Dorris, a spokeswoman for the coordinated procedures” for protecting chil - Survivors Network of those Abused by dren, assisting victims of abuse, dealing Priests, known as SNAP, said in a statement with accused priests, training clergy and that “the Vatican abuse guidelines will cooperating with civil authorities. -

School Held Ih Home Boasting 16 Children Denvercatholic

r u Total Press Run, Att Editions, High Above SOOfiOO; Denver Catholie Register, SCHOOL HELD IH HOME BOASTING 16 CHILDREN Race Bias Charged in Camp Carson, Contenta Copyrighted by the Catholic Preu Society, Inc., 1942— Permission to Reproduce, Ezeeptlnf on >^icles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Arsenal Project Is Investigated Paul Kawchak Family U. S. Senator Johnson Raps DENVERCATHOLIC Furnishes Most of Discrimination in War Work Students for Classes / U.S. Senator Ed C. Johnson of Hale, near Pando, have been jsonnel director for the project Colorado has entered the battle ironed out, new accusations o f dis prime contractors; George Bray- field, president o f the Colorado to end discrimination aj^inst crimination involving the dis Neighbor Children Also Attend Unique Vacation Spanish-speaking: Americans in State Federation of Labor, and REGISTER war work that was launched by charge of two Spanish-speaking George Maurer, president of the The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. Wo Have the Denver Catholic Register two men in Camp Carson, south of Denver Building and Construction Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services. Term 18 Miles From Craig; Father Paul weeks ago when it revealed Colorado Springs, have flared and Trades council. Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. charges made by the Very Rev. charges involving the Rocky Pando Situation Outra(ooni 0. Slattery Is Pastor John Ordinas, C.R., of St. Caje- Mountain arsenal project, east of “ Such a situation as was re VOL. XXXVU. -

Conclave 1492: the Election of a Renaissance Pope

Conclave 1492: The Election of a Renaissance Pope A Reacting to the Past Microgame Instructor’s Manual Version 1 – August 2017 William Keene Thompson Ph.D. Candidate, History University of California, Santa Barbara [email protected] Table of Contents Game Summary 1 Procedure 3 Biographical Sketches and Monetary Values 4 Role Distribution and Vote Tally Sheet 6 Anticipated Vote Distributions 7 Conclave Ballot Template 8 Role Sheets (23 Cardinals) 9 Additional Roles 33 Extended Gameplay and Supplementary Readings 34 William Keene Thompson, UC Santa Barbara [email protected] Conclave 1492: The Election of a Renaissance Pope The Situation It is August 1492. Pope Innocent VIII has died. Now the Sacred College of Cardinals must meet to choose his successor. The office of Pope is a holy calling, born of the legacy of Saint Peter the first Bishop of Rome, who was one of Christ’s most trusted apostles. The Pope is therefore God’s vicar on Earth, the temporal representation of divine authority and the pinnacle of the church hierarchy. However, the position has also become a political role, with the Holy Father a temporal ruler of the Papal States in the center of the Italian peninsula and charged with protecting the interests of the Church across Christendom. As such, the position requires not only spiritual vision but political acumen too, and, at times ruthlessness and deception, to maintain the church’s position as a secular and spiritual power in Europe. The Cardinals must therefore consider both a candidate’s spiritual and political qualifications to lead the Church. -

The Congregation of the Mission and the Colégio Da Purificação in Evora

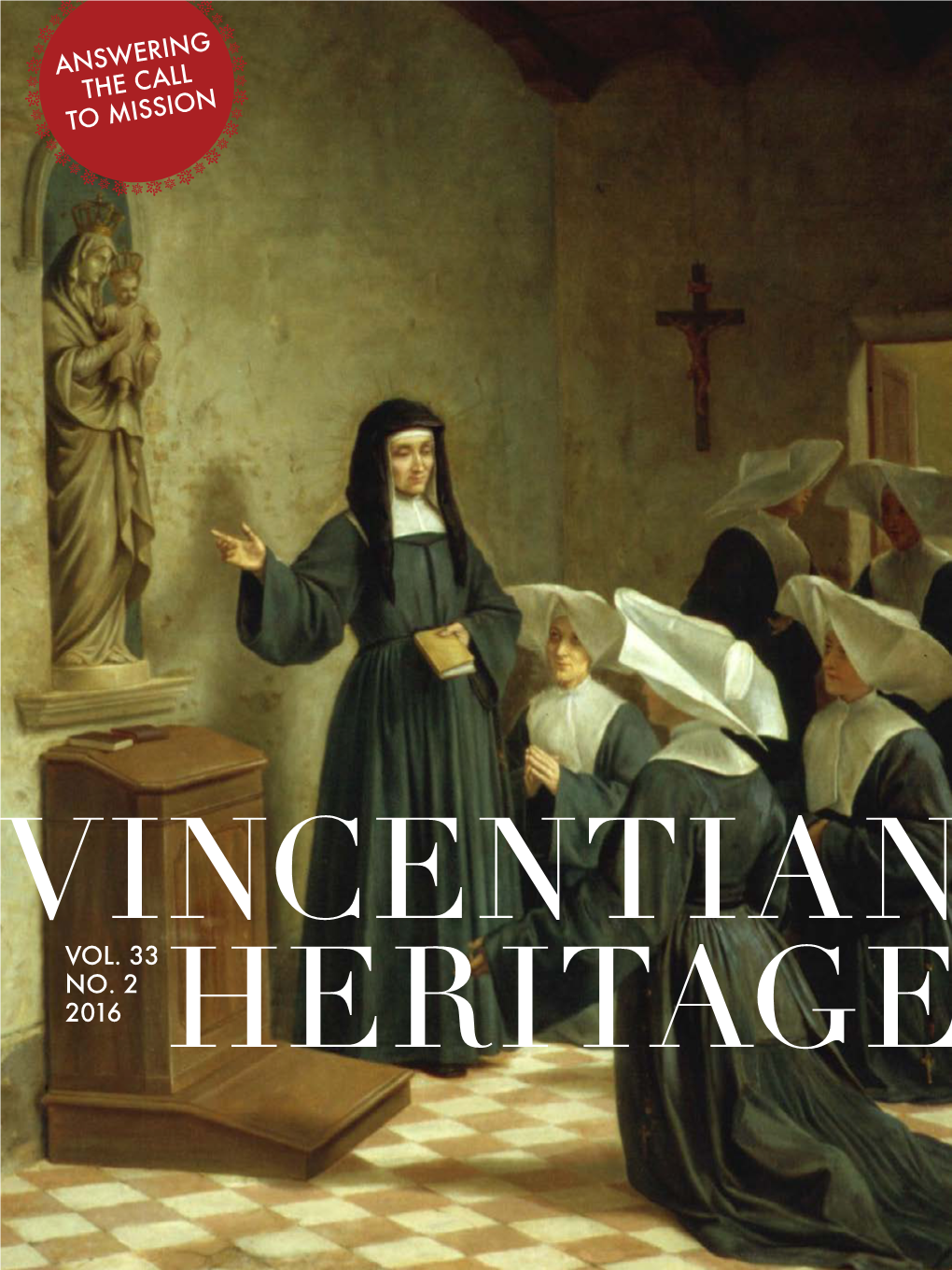

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 33 Issue 2 Article 1 Fall 9-20-2016 Succeeding the Jesuits: The Congregation of the Mission and the Colégio da Purificação in vE ora Sean A. Smith Ph.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation Smith, Sean A. Ph.D. (2016) "Succeeding the Jesuits: The Congregation of the Mission and the Colégio da Purificação in vE ora," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol33/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Succeeding the Jesuits: The Congregation of the Mission and the Colégio da Purificação in Evora SEAN ALEXANDER SMITH, PH.D. Q Q QQ Q QQ QQ Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q next BACK TO CONTENTS Q Q Q Q Q Q article Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q he eighteenth-century is generally regarded as a time of wilting prestige for Catholic religious institutes, above all the Society of Jesus. In 1773, the universal dissolution Tof the Society, once one of the most visible and powerful religious bodies in the Catholic church, came at the end of European-wide repressive attacks starting in the 1750s. In 1758, the Jesuits were accused of widespread abuses and scandalous conduct in Portugal and its colonies. -

A HEART for OTHERS, Is the History of Our Sisters' Labour of Love, Spanning One Hundred and Sixteen Years

A EART for Rosemary Clerkin SHJM A HfS~T OTHERS FATHER PETER VICTOR BRAUN 1825-1882 A OTHERS ROSEMARY CLERKIN, SHJM © Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, Chigwell 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 A Priest Forever . 1 2 Small Beginnings . 6 3 Jesus Christ and the Poor . 13 4 Only What God Wills . 19 5 Exile in England . 23 6 Servants of the Sacred Heart . 30 7 Love One Another . • . 34 8 Difficult Developments . 44 9 Two Roads Diverge . 55 10 Spreading Our Wings . 62 11 Works of Mercy . 71 12 Beneath the Southern Cross . 76 13 Llke to a Grain of Mustard Seed . 85 14 The Long Night of War . • . 92 15 Step Out in Faith . 104 16 The Dawn ofa New Day . 117 Bibliography . 125 (i) (ii) FOREWORD This year we celebrate the centenary of the death of our founder, Reverend Father Victor Braun. Many celebrations of a spiritual nature will commemorate this year which is of special significance to our congregation. When the year is over, and so that we do not forget the many valuable insights we have received about our founder, it was thought appropriate to update the history of our congregation. To see its growth and development since Chigwell and LIKE TO A GRAIN OF MUSTARD SEED were written, Sister Rosemary Clerkin did a monu mental task of research to find the necessary data. She travelled far and. wide, both to interview people and to peruse the many manuscripts which yielded a wealth of relevant information. A HEART FOR OTHERS, is the history of our Sisters' labour of love, spanning one hundred and sixteen years. -

SC Masters Redesign.Qxd

July 27 to August 2, 2011 www.scross.co.za r5,50 (incl VAT rSA) reg No. 1920/002058/06 No 4736 Who cares WYD: Madrid’s Meet Muhammad, for the trouble with prophet of prisoners? rosaries, bananas Muslims Page 9 Page 4 Page 10 Volunteer, priest tells SA youth BY CLAIrE MATHIESON the building up,” said Fr Mabusela. The young international volunteers have HE spirit of volunteering needs to be already gained life lessons through the instilled in South African youth, experience, Fr Mabusela said. Taccording to Fr Sammy Mabusela CSS, “They’ve learnt about the challenges the national youth chaplain. that other people around the world experi - The priest is currently working with a ence. They’ve also learnt there are lots of group of Italian volunteers across the arch - things we all have in common.” diocese of Pretoria. He said the Italian youth have had their The group of 17- and 18-year-olds trav - “eyes opened” to the world. elled to South Africa from the city of Fr Mabusela wants to promote volun - Verona with their priest Fr Simone Pianti - teering by South African youth. ni. The two Stigmatine priests met during “I keep in touch with what’s important Fr Mabusela’s tenure in Tanzania where he to the youth and I try to inspire them,” ran a school. Part of the congregation’s said Fr Mabusela, who uses Facebook and charism is youth ministry and Fr Piantini Twitter to communicate with the nation’s said he would encourage youth from his youth. diocese to volunteer in Africa. -

Paul in Rome: a Case Study on the Formation and Transmission of Traditions

PAUL IN ROME: A CASE STUDY ON THE FORMATION AND TRANSMISSION OF TRADITIONS Pablo Alberto Molina A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: James Rives Bart Ehrman Robert Babcock Zlatko Plese Todd Ochoa © 2016 Pablo Alberto Molina ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Pablo Molina: Paul in Rome: A Case Study On the Formation and Transmission of Traditions (Under the direction of James Rives) Paul is arguably the second most important figure in the history of Christianity. Although much has been written about his stay and martyrdom in Rome, the actual circumstances of these events — unless new evidence is uncovered — must remain obscure. In this dissertation I analyze the matter from a fresh perspective by focusing on the formation and transmission of traditions about Paul’s final days. I begin by studying the Neronian persecution of the year 64 CE, i.e. the immediate historical context in which the earliest traditions were formed. In our records, a documentary gap of over thirty years follows the persecution. Yet we may deduce from chance remarks in texts written ca. 95-120 CE that oral traditions of Paul’s death were in circulation during that period. In chapter 2, I develop a quantitative framework for their contextualization. Research has shown that oral traditions, if not committed to writing, fade away after about eighty years. Only two documents written within that crucial time frame have survived: the book of Acts and the Martyrdom of Paul (MPl). -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer Reputation, patronage and opportunism Citation for published version: Richardson, C 2018, 'Reputation, patronage and opportunism: Andrea Sansovino arrives in Rome', Sculpture Journal, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 177-192. https://doi.org/10.3828/sj.2018.27.2.3 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3828/sj.2018.27.2.3 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Sculpture Journal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Reputation, Patronage and Opportunism: Andrea Sansovino Arrives in Rome In the first decade of the sixteenth century, artists and architects travelled to work in Rome to help fulfil the ambitions of Julius II (reg. 1503–13), who envisioned the city as the triumphant embodiment of papal power.1 Michelangelo in 1499 and Raphael in 1508, for example, moved to the papal city relatively early in their careers, lured by the promise of wealthy patrons.2 Others, including Donato Bramante who arrived in Rome from Milan for the 1500 jubilee, had established their workshops and could rely on extensive cultural and political networks.3 Andrea Sansovino (1467–1529) was documented in Rome from 1505, responding to Julius II’s commission for the tomb monument of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza in Santa Maria del Popolo (fig. -

SC Masters Redesign.Qxd

April 20 to April 26 , 2011 www.scross.co.za R5,50 (incl VAT RSA) Reg No. 1920/002058/06 No 4722 Why university students Reflection: Brother: I know are converting to Saved by one what it’s like to the Catholic faith man’s sacrifice be dead Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Hope&Joy programme to launch May 8 STAff REpoRTER CATHOLIC network, Hope&Joy, focus - ing on popular education for adults, Awill officially launch on May 8 with a website, free SMS service, media articles and homilies at Mass. Hope&Joy has brought together dozens of Catholic bodies to help Southern African Catholics to understand and live out the promise of Vatican II, “to be Church in the Modern World”, according to Raymond Perri - er, who has spearheaded the programme. Hope&Joy, which is unique to the South - ern African region, “functions as a network; there is no central head office”, said Mr Perri - er, who is also director of the Jesuit Institute South Africa. “Through the Hope&Joy net - work, organisations will be able to work together, share resources and share a com - mon logo.” Individual elements will include booklets, newspaper columns, one-off lectures, videos, training courses, parish events, radio pro - grammes and so on that will be linked under the name Hope&Joy. “Because the network is open, there will be space to take initiatives at different levels: diocesan departments, national and diocesan Catholic organisations, parish groups, schools, religious congregations, sodalities and other grassroots organisations, or even individuals,” he said. A website ( www.hopeandjoy.org.za ) and Facebook group “will help the different ele - ments come together and cross-fertilise”. -

Alms for the King

chapter 4 Alms for the King Half way up the labyrinth of streets that lead to the Castelo São Jorge, stands the Cathedral of Lisbon. Dedicated to Santa Maria Maior, the construction of the original church was said to have begun in 1147, just after the conquest of the city by Portugal’s first king, D. Afonso Henriques. The Romanesque features of its western façade look more like a fortress than a place of worship: a defiant bastion of the Reconquista built on the site of the Almoravid mosque. For cen- turies Lisbon had been the principal city of the region, owing to its strategic position on the estuary of the Tagus. According to the Manueline chronicler Duarte Galvão, it was the Cathedral of Lisbon that D. Afonso Henriques selected, in 1173, as the final resting place for the holy relics of St. Vincent of Saragossa.1 These relics, and the pilgrims who flocked to see them, would, over the years generate the wealth that was necessary to bring the Reconquista and the building itself to completion, thereby cementing Portugal’s position as a sovereign kingdom. During the reign of Manuel i, the centralization of the religious administra- tion had also become an acute priority. In the reign of João ii, the influence of the absentee Archbishop of Lisbon, the Cardinal of Alpedrinha, had interfered with Portugal’s diplomatic initiatives in Rome. Resident in the Holy City from 1478 until his death thirty years later, the Cardinal of Alpedrinha had controlled episcopal appointments, using them to further the interests of his large family, rather than furthering the interests of his king.