In Re Musical Instruments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FMI Wholesale 2006 Price List

FMI Wholesale 2006 Price List T 800.488.1818 · F 480.596.7908 Welcome to the launch of FMI Wholesale, a division of Fender Musical Instruments Corp. We are excited to offer you our newest additions to our family of great brands and products. Meinl Percussion, Zildjian®, Tribal Planet, Hal Leonard®, Traveler Guitar, Practice Tracks, Pocket Rock-It, are just a few of the many great names that you’ll find in this Winter Namm Special Product Guide. You’ll find page after page of new and exciting profit opportunities to take advantage of as we welcome the new year. In the coming weeks, you will also be receiving our brand new product catalog showcasing all of the great products that FMI Wholesale will be offering to you in 2006. Our goal, along with that of our strategic business partners, is to provide you with a new and easy way to do business. In the enduring Fender tradition, we aim to provide best-in-class products, superior service and our ongoing commitment to excellence that will be second to none. Our programs will be geared towards your profitability, so in the end, doing business with FMI Wholesale will always make good sense. Thank you for the opportunity to earn your business. We look forward to working with you in 2006. Sincerely, The FMI Wholesale Sales and Marketing Team Dealer Dealer Number Contact PO Number Ship To Date Terms: Open Account GE Flooring Notes FREIGHT POLICY: 2006 brings new opportunities for savings in regards to freight. To maximize your profitability‚ our newly revamped freight program continues to offer freight options for both small and large goods. -

2013 Full Line Catalog 2013

Electric Guitars, Electric Basses, Acoustic Guitars, Amplifiers, Effects & Accessories 2013 Accessories Effects & Amplifiers, Guitars, Electric Acoustic Electric Basses, Guitars, www.ibanez.com 1726 Winchester Road, Bensalem, PA 19020 · U.S.A. · ©2012 Printed in Japan NOV12928 (U) For Authorized Dealers Only - All finishes shown are as close as four-color printing allows. CATALOG - All specifications and prices are subject to change without notice. 2013 FULL LINE Table of Contents Solid Body Electric Guitars Signature Models 6-10 Iron Label RG/S 11-13 RG/GRG/GRX/MIKRO 13-26 RGA 26 RGD 27 S 28-31 X 32-33 FR 33 ARZ 34 AR 34-35 ART 35-36 Jumpstart 37 Hollow Body Electric Guitars Signature Models 40-41 Artstar 41 Artcore Expressionist 42-44 Artcore 44-47 Electric Basses Signature Models 50-51 SR 51-61 Grooveline 62-63 BTB 64-65 ATK 66-67 Artcore 67-68 GSR/MIKRO 68-73 Jumpstart 73 Acoustic Guitars Signature Models 76 Artwood 77-81 PF 82-85 SAGE 85 AEG 86 AEL 87 AEF 88-89 EW 90-91 Talman 91-92 AEB 92 SAGE Bass 93 Classical 93-95 Ukulele 95-96 Banjo 96 Resonator 96 Mandolin 97 Jampack 98 Amplifiers/Effects/Accessories Tube Screamer Amplifier 100-101 Wholetone 101 Promethean 102-103 Sound Wave 103 Troubadour 104-105 IBZ 105 Tube Screamer 106 9 Series 107 Echo Shifter 108 Signature Effect Pedal 109 Wah Pedals 109 Tuners 110 Cables & Adapter 110 Stand 111 Tremolo Arm 111 Picks 111 Cases/Straps 112 Bags/Microphone Stand 113 02 for more information visit www.Ibanez.com for more information visit www.Ibanez.com 03 04 for more information visit www.Ibanez.com -

HYPEBEAST UNVEILS FENDER® X HYPEBEAST STRATOCASTER

HYPEBEAST UNVEILS FENDER® x HYPEBEAST STRATOCASTER Download assets HERE Hypebeast today announces the launch of the HYPEBEAST Stratocaster®, presented in collaboration with Fender®, the iconic global guitar brand. Hypebeast shares strong bonds with a global network of content creators, and is dedicated to maintaining close interactions with established musicians across genres, as well as discovering emerging talent and bringing that to Hypebeast’s cultural realm. Constantly inspired by such meaningful connections, Hypebeast is thrilled to be joining hands with Fender to present this vintage-style guitar in Hypebeast’s signature navy. “Fender has always been closely connected to musical culture since its founding in 1946. Similarly, Hypebeast is one of the most influential online media in lifestyle and culture. Through this collaboration, we’re looking forward to bringing music closer to other cultural realms, as we share a passion for music amongst a generation immersed in fashion and lifestyle,” said Edward Cole President of APAC, Fender Music Corporation. www.hypebeast.com [email protected] Page 1 of 2 The model is based on the globally acclaimed Made in Japan Stratocaster featuring a 9.5" radius and 22 Medium Jumbo frets, delivering a sophisticated playability with modern feel optimal for any musical genres and playing style. The guitar painted in Hypebeast’s signature navy color from top to bottom - including the fingerboard and headstock - is sure to catch the attention of any culture-sensitive player. This special edition guitar is available exclusively at Fender.com in Japan, US and UK regions, as well as HBX.com in extremely limited quantities. To read full product specifications, please visit fender.com for more information. -

W Irin G D Iag Ram S

1 s A 2 3 4 5 B 6 500k ON/ON/ON 7 m 8 9 C 10 11 500k a 12 ON ON 47nF r Jetzt mit Schaltplan zu jeder Schaltung! g a i d 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 nicht mehr ganz so g n kleine Sammlung i r i von Schaltplänen w Version 4.03 WITH AN GERM GLISH EN Y ONAR DICTI NOW! Passive Schaltungen für E-Bässe sowie einige aktive Schaltungen • Historische Schaltungen • Umbauten & Eigenbauten • Modifikationen • Grundlagen & Theorie • Pläne selbst entwerfen Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 1 Deckblatt 54 1.1.651 Fender Bass V 1965 - 70 2 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 55 1.1.661 Fender Bass VI 1961 - 75 6 1 Vorwort 56 1.1.666 Fender Bass VI Pawn Shop 2013 x x x 57 1.1.731 Fender P.S. Reverse Jaguar 2012 8 1 Historische Schaltungen 58 1.1.741 Fender La Cabronita Boracho 2012 9 1.1.101 Fender Precision Bass 1951 - 56 59 1.1.771 Fender Roscoe Beck Bass 2004 10 1.1.103 Fender Precision Bass 1952 - 53 60 1.1.811 Fender Coronado I Bass 1966 - 70 11 1.1.106 Fender Precision Bass 1954 61 1.1.821 Fender Coronado II Bass 1966 -72 12 1.1.108 Fender Precision Bass 1955 62 1.1.921 Fender Performer Bass FB-555 1982 13 1.1.121 Fender Precision Bass '51 2003 63 1.2.111 Squier CV 50's P-Bass 04.2008 14 1.1.124 Fender Precision Bass OPB'54 1983 64 1.2.113 Squier CV 50's P-Bass 09.2008 15 1.1.131 Fender Prec. -

Ibanez Market Strategy

Ibanez Market Strategy Billy Heany, Jason Li, Hyun Park, Alena Noson Strategic Marketing Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Firm Analysis.................................................................................................................................................... 4 Key Information about the Firm ........................................................................................................... 4 Current Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................ 5 Current Performance ................................................................................................................................. 6 SWOT ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 Current Life Cycle Stage for the Product .......................................................................................... 8 Current Branding Strategy ...................................................................................................................... 9 Industry Analysis .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Market Review ........................................................................................................................................ -

Maintenance Manual STRING REPLACEMENT Strings Will Deteriorate Over Time, Causing Buzzing Or Inaccurate Pitch

Maintenance Manual STRING REPLACEMENT Strings will deteriorate over time, causing buzzing or inaccurate pitch. Replace the strings whenever your strings begin to rust or become discolored. We recommend that you replace all of the strings as a set at the same time. Bent, twisted, or damaged strings will not produce the appropriate quality sound and therefore should not be used. Wind the string around the tuning machine post two or three times, making sure to wind from top to bottom. Wind about 5–7 cm of string for guitar and 8–10 cm for bass. Do not wind the string on top of itself. The strings should be replaced one by one instead of removing all the strings at once. This is done to avoid stress on the neck and to reduce the risk of affecting tremolo balance. ※ The method for removing and installing strings attached to a tremolo/bridge will differ depending on the type of tremolo/bridge. For details, refer to the section for the tremolo/bridge installed on your guitar. Visit our web site (http://www.ibanez.com) for details. TUNING When shipped from the factory, Ibanez guitars are set up using the following tunings. ■ Guitar 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th 8th 9th 6-strings E B G D A E - - - 7-strings E B G D A E B - - 8-strings D# A# F# C# G# D# A# F - 9-strings E B G D A E B F# C# ■ Bass 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 4-strings G D A E - - 5-strings G D A E B - 6-strings C G D A E B There are exceptions to some models. -

CRANFORD, GARWOOQ and KENIL WORTH

•v :/• ;Page 28 CRANFOHD (N.J.) CHRONICLE Thursday, May 16,1985 Where else but Kings? -..I' - 7 SERVING CRANFORD, GARWOOQ and KENIL WORTH Vol. 92 No. 20 Published Every Thursday Thursday, May 23,1985 USPS 136 800 Second Class Postage Paid Cranford, N.J. 25 CENTS Lawmen CHS chemists win _ pan-fry or deep-fry with no fuss at all. , Crabs you'll ever see. Pop one in a deli'roll andjnake a sandwich of it. Put a few on the charcoal Costanzo in prison as parole datenears grill and make a banquet of it. From the squeeze of a fresh lemon.to the zest ot New Jersey title And to see that you savor the best of them, we make certain that the finest ; By STUA RT bars personally to a senior hearing tuated to as late as April 1987 but was f a gourmet sauce, you can be as plain or, as fancy as you like. -. •.. 1 mation will be presented. Chesapeake Bay shell-fishermen reserve their prize catches for Kings. The murderer of Michelle H officer under a new victim input pro- moved up because of work and other JWiss_D_eMarzo was killed June 20, ... The Cranford High School ad- individuai~a^Srds for outstan- And when it'comes to special recipes for grilling, saucing, pan-trying and zo is eligible ipr ^parole consideration cedure. , _:_-_ ihhd 1|78 shortly before she was scheduled vanced chemistry team finished ding performance. On the Each crab is rushed to us in special seaweed packing to make sure it's ahve- first in the state in the Chemistry deep-frying, they're all yours in our Seafood Corner \, , -, o*,Cu ir .and could be fretJ by Christmas. -

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your Questions Answered…

The Fender Custom Shop and “Blackie” Your questions answered… A few days before the launch of the Fender Eric Clapton “Blackie” Reissue, Mike Eldred – Director of Sales and Marketing for the Fender Custom Shop, was interviewed by Guitar Center for his personal account of the “Blackie” Reissue project. GC: So Mike, what’s your role at Fender, and in the Custom Shop specifically? Mike: I’m Director of Sales and Marketing for the FMIC Custom Division, and that encompasses all brands: Tacoma, Guild, Gretsch, Fender, Charvel, Jackson, and the amplifiers. GC: What is it about “Blackie” that makes it so special, even within that special world? Mike: It’s an iconic Stratocaster. The story about the guitar is really such a great story about how Eric bought the guitar--bought several guitars--and then pieced together basically just one guitar from a bunch of different parts. So he actually built the guitar, which is very unique when it comes to iconic guitars like this. A lot of times they’re just bought at a store or something like that. But here, an artist actually built the guitar, and then used it on so many different recordings, and it was so identified with Eric Clapton and his musical legacy. GC: Then, after 35 years of ownership, he offered it up for sale. What did Fender think when they heard that Guitar Center had bought Blackie at auction for almost a million dollars? Mike: Just that we were glad that it was sold to someone we have a relationship with. The concern that we had was that somebody was going to buy it and then just lock it away and that would be that, or some private collector would buy it or something like that. -

Acoustic Guitar Buying Guide

Acoustic Guitar Buying Guide A Starter’s Guide to Buying an Acoustic Guitar Shopping for an acoustic guitar can be an overwhelming experience. Because guitar makers use a wide range of woods, hardware, and design elements, there are many factors to consider. Specifically, there are four primary areas you will want to consider and/or know about before you start shopping. Table of Contents Purpose and Budget - How are you going to use your guitar, and how much will you spend? Construction and Design - Learn the basics before you shop. Styles and Sound - Understand how different features affect the sound of the guitar. Acoustic Guitar Variants - 12-string acoustics and alternate body shapes Don't Forget Personal Preference Glossary Purpose and Budget Before you think about brand names or body styles, consider what you are going to use the guitar for, and how much money you have to spend on one. Skill Level - Amateur or Advanced If you are a new player who is looking for an instrument to learn on, you may not want to spend too much on a high-end acoustic guitar just yet. Thanks to modern manufacturing techniques, there is a wide selection of good, low- to mid-range acoustic guitars to choose from. But maybe you are an experienced player who is ready to upgrade to a better guitar. In that case, it is important to know the difference between tonewoods, and how the soundboard effects resonance. Purpose - Acoustic-Electrics Expand Your Options Will you be playing with a band, or taking your guitar to public events such as open mic nights? If so, you may want to consider an acoustic-electric guitar. -

The Music Begins Here SBO Level 1 Level 2 JANUARY 25-28, 2018 • ANAHEIM, CALIFORNIA Level 1 LEVEL 2: MEETING ROOMS 200–299 Hilton Hotel Inmusic Brands Inc

ANAHEIM CONVENTION CENTER 326A 326B 369 370 LEVEL 3: Grotrian Piano Company GmbH Yangtze River Mendelssohn Piano Mason & Hamlin MEETING ROOMS & BOOTHS 300–799 THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS LEVELS & HOTELS Piano 323 (Shanghai) Reserved Wilh. Steinberg Fender Fazioli Marketing Co., Ltd. 303D Group Inc. 366 388 Fender 321 Pianoforti Niendorf SPA Dynatone Flügel AT A GLANCE Musical - 319 Corp. und PianoDisc Musical Klavierfabrik 300B2 Samick Instruments 318 340 362GmbH 384 391 Instruments 317 Corporation Music North Corporation 314 335 American A.Geyer Music Corp. Inc. Kawai America Corp 334 356 376 390 393 Schimmel Piano Ravenscroft North Corporation Lowrey ACC North 304BCD Pianos Vienna W. Schimmel 303BC W Katella Ave American International, 374 Gretsch Guitars Music Pianofortefabrik Inc. Inc. Pearl River Piano Jackson 308 330 352 372 389 392 GmbH Guangzhou Pearl River Amason PROFESSIONAL ACC 300E Charvel Digital Musical Instr 305 L88A L88B 300B 300A 304A EVH 303A Arena Outdoor Cafe S West Street 303 • Level 2 • Level 2 • Level 2 • Level 2 DJ String • Lobbies E & D 300a & PTG Museum Display • Lobby B Arena • Mezzanine • Lobby C • Lobby B &Piano Bow Plaza Events DJ/Pro Audio Level 2 Level 3 The Music Begins Here SBO Level 1 Level 2 JANUARY 25-28, 2018 • ANAHEIM, CALIFORNIA Level 1 LEVEL 2: MEETING ROOMS 200–299 Hilton Hotel inMusic Brands Inc. Akai Professional Hotel Way Denon DJ Import Reserved Exhibitor Numark Music Grand Reserved Reserved RANE Reserved Plaza NAMM Meeting Alesis USA, Events D'Angelico Alto Professional Corp. Mackie 209B 206B MARQ Lighting 203B Guitars 210D 210D1 207D 204C Ampeg Hall E Yamaha Zemaitis Guitars Reserved Exhibitor Meinl W Convention Way Taylor Greco Guitars Meeting 212AB 210C 209A 207C 206A Pearl Corporation 203A 201CD Marriott Hotel Guitars Marshall Adams Musical Instruments Pacific Drums & Amplification Percussion Sky Bridge to ACC North Dean Guitars Drum Workshop, Inc. -

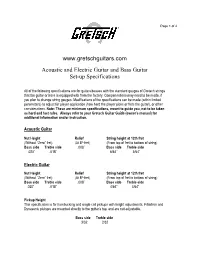

Gretsch Setup Specs

Page 1 of 2 www.gretschguitars.com Acoustic and Electric Guitar and Bass Guitar Set-up Specifications All of the following specifications are for guitars/basses with the standard gauges of Gretsch strings that the guitar or bass is equipped with from the factory. Compensations may need to be made, if you plan to change string gauges. Modifications of the specifications can be made (within limited parameters) to adjust for player application (how hard the player picks or frets the guitar), or other considerations. Note: These are minimum specifications, meant to guide you, not to be taken as hard and fast rules. Always refer to your Gretsch Guitar Guide (owner's manual) for additional information and/or instruction. Acoustic Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .020” .018” 6/64” 5/64” Electric Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .020” .018” 4/64” 4/64” Pickup Height This specification is for humbucking and single coil pickups with height adjustments. Filtertron and Dynasonic pickups are mounted directly to the guitar’s top, and are not adjustable. Bass side Treble side 3/32 2/32 Page 2 of 2 Bass Guitar Nut Height Relief String height at 12th fret (Without “Zero” fret) (At 8th fret) (From top of fret to bottom of string) Bass side Treble side .008” Bass side Treble side .022” .022” 4/64” 4/64” Pickup Height This specification is for humbucking and single coil pickups with height adjustments. -

Guitar Cross Reference Updated 02/22/08 Includes: Acoustic, Bass, Classical, and Electric Guitars

Gator Cases Guitar Cross Reference Updated 02/22/08 Includes: Acoustic, Bass, Classical, and Electric Guitars Use Ctrl-F to search by Manufacturer or Model Number Manufacturer Model Type Fits (1) Fits (2) Fits (3) Fits (4) Fits (5) Alvarez AC60S Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez Artist Series AD60K Dao Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD60S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD70S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez Artist Series AD80SSB Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez CYM95 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez MC90 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez RC10 Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Alvarez RD20S Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez RD8 Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Alvarez RD9 Acoustic Guitar GL-Dread-12 GC-Dread-12 GPE-Dread G-Tour Dread-12 GW-Dread Aria PE-STD Series Electric Guitar GL-LPS GC-LPS GPE-LPS G-Tour LPS GW-LPS Cordoba 32E Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Cordoba 32EF Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic GWE-Class GW-Classic Cordoba 45FM Classical Guitar GL-Classic GC-Classic GPE-Classic