A Sublime Invasion: Meyerbeer, Balzac, and the Opera Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

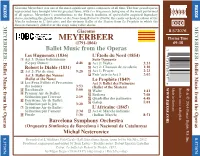

Meyerbeer Was One of the Most Significant Opera Composers of All Time

NAXOS NAXOS Giacomo Meyerbeer was one of the most significant opera composers of all time. The four grand operas represented here brought him his greatest fame, with Les Huguenots being one of the most performed of all operas. Meyerbeer’s contributions to the French tradition of opéra-ballet acquired legendary status, including the ghostly Ballet of the Nuns from Robert le Diable; the exotic orchestral colour of the Marche indienne in L’Africaine; and the virtuoso Ballet of the Skaters from Le Prophète in which the dancers famously glided over the stage using roller skates. DDD MEYERBEER: MEYERBEER: Giacomo 8.573076 MEYERBEER Playing Time (1791-1864) 69:38 Ballet Music from the Operas 7 Les Huguenots (1836) L’Étoile du Nord (1854) 47313 30767 1 Act 3: Danse bohémienne Suite Dansante Ballet Music from the Operas Ballet Music from (Gypsy Dance) 4:46 9 Act 2: Waltz 3:32 the Operas Ballet Music from Robert le Diable (1831) 0 Act 2: Chanson de cavalerie 1:18 2 Act 2: Pas de cinq 9:28 ! Act 1: Prayer 2:23 Act 3: Ballet des Nonnes @ Entr’acte to Act 3 2:02 (Ballet of the Nuns) Le Prophète (1849) 3 Les Feux Follets et Procession Act 3: Ballet des Patineurs 8 des nonnes 3:53 (Ballet of the Skaters) www.naxos.com Made in Germany Booklet notes in English ൿ 4 Bacchanale 5:00 # Waltz 1:41 & 5 Premier Air de Ballet: $ Redowa 7:08 Ꭿ Séduction par l’ivresse 2:19 % Quadrilles des patineurs 4:48 6 Deuxième Air de Ballet: 2014 Naxos Rights US, Inc. -

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

IN SUMMER Lucerne Is a Wagner City

Der Ring des Nibelungen IN SUMMER Lucerne is a Wagner city. For six years – from 1866 to 1872 – the com- poser resided at the Villa Tribschen. This was a decisive period for him artistically as well as personally. It was here that he completed Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and resumed work on The Ring of the Nibelung, composing both the third act of Siegfried and Götterdäm- merung. Wagner’s Lucerne years also represented a turning point in his personal life. He moved into his new home on Lake Lucerne with Cosima von Bülow, whom he then married on 25 August 1870 in the Protestant parish church. And it was in Tribschen that two of the couple’s three children – their daughter Eva and son Siegfried – were born. To mark the composer’s 200th birthday, LUCERNE FESTIVAL is presenting the first complete performance of theRing cycle in the Wagner city of Lucerne, with the English conductor Jonathan Nott, the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, and internationally acclaimed Wagner singers, including Albert Dohmen as Wotan, the ruler of the gods, Petra Lang making her role debut as Brünnhilde, Torsten Kerl as Siegfried, Klaus Florian Vogt in the role of Siegmund, and the Russian bass Mikhail Petrenko in a threefold assignment as Fafner, Hunding, and Hagen. This concert presentation of the epoch-making work will enable us to focus on Wagner the musical revolutionary. The highly acclaimed acoustics of the KKL Lucerne’s Salle blanche concert hall will bring out the sonic details and nuances of Wagner’s astounding orchestration with a transparency that has not been heard before. -

Assenet Inlays Cycle Ring Wagner OE

OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 1 An Introduction to... OPERAEXPLAINED WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson 2 CDs 8.558184–85 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 2 An Introduction to... WAGNER The Ring of the Nibelung Written and read by Stephen Johnson CD 1 1 Introduction 1:11 2 The Stuff of Legends 6:29 3 Dark Power? 4:38 4 Revolution in Music 2:57 5 A New Kind of Song 6:45 6 The Role of the Orchestra 7:11 7 The Leitmotif 5:12 Das Rheingold 8 Prelude 4:29 9 Scene 1 4:43 10 Scene 2 6:20 11 Scene 3 4:09 12 Scene 4 8:42 2 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 3 Die Walküre 13 Background 0:58 14 Act I 10:54 15 Act II 4:48 TT 79:34 CD 2 1 Act II cont. 3:37 2 Act III 3:53 3 The Final Scene: Wotan and Brünnhilde 6:51 Siegfried 4 Act I 9:05 5 Act II 7:25 6 Act III 12:16 Götterdämmerung 7 Background 2:05 8 Prologue 8:04 9 Act I 5:39 10 Act II 4:58 11 Act III 4:27 12 The Final Scene: The End of Everything? 11:09 TT 79:35 3 OE Wagner Ring Cycle Booklet 10-8-7:Layout 2 13/8/07 11:07 Page 4 Music taken from: Das Rheingold – 8.660170–71 Wotan ...............................................................Wolfgang Probst Froh...............................................................Bernhard Schneider Donner ....................................................................Motti Kastón Loge........................................................................Robert Künzli Fricka...............................................................Michaela -

The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: the Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring Des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 6 The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Matthew Timmermans University of Ottawa Recommended Citation Timmermans, Matthew (2015) "The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen," Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 6. The Bayreuth Festspielhaus: The Metaphysical Manifestation of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen Abstract This essay explores how the architectural design of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus effects the performance of Wagner’s later operas, specifically Der Ring des Nibelungen. Contrary to Wagner’s theoretical writings, which advocate equality among the various facets of operatic production (Gesamtkuntswerk), I argue that Wagner’s architectural design elevates music above these other art forms. The evidence lies within the unique architecture of the house, which Wagner constructed to realize his operatic vision. An old conception of Wagnerian performance advocated by Cosima Wagner—in interviews and letters—was consciously left by Richard Wagner. However, I juxtapose this with Daniel Barenboim’s modern interpretation, which suggests that Wagner unconsciously, or by a Will beyond himself, created Bayreuth as more than the legacy he passed on. The juxtaposition parallels the revolutionary nature of Wagner’s ideas embedded in Bayreuth’s architecture. To underscore this revolution, I briefly outline Wagner’s philosophical development, specifically the ideas he extracted from the works of Ludwig Feuerbach and Arthur Schopenhauer, further defining the focus of Wagner’s composition and performance of the music. The analysis thereby challenges the prevailing belief that Wagner intended Bayreuth and Der Ring des Nibelungen, the opera which inspired the house’s inception, to embody Gesamtkunstwerk; instead, these creations internalize the drama, allowing the music to reign supreme. -

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France the Politics of Halevy’S´ La Juive

Opera, Liberalism, and Antisemitism in Nineteenth-Century France The Politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive Diana R. Hallman published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Diana R. Hallman 2002 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2002 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Dante MT 10.75/14 pt System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Hallman, Diana R. Opera, liberalism, and antisemitism in nineteenth-century France: the politics of Halevy’s´ La Juive / by Diana R. Hallman. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in opera) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 65086 0 1. Halevy,´ F., 1799–1862. Juive. 2. Opera – France – 19th century. 3. Antisemitism – France – History – 19th century. 4. Liberalism – France – History – 19th century. i. Title. ii. Series. ml410.h17 h35 2002 782.1 –dc21 2001052446 isbn 0 521 65086 0 -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert Le Diable Online

cXKt6 [Get free] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Online [cXKt6.ebook] The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable Pdf Free Richard Arsenty ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4398313 in Books 2009-03-01Format: UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .50 x 5.70l, .52 #File Name: 1847189644180 pages | File size: 19.Mb Richard Arsenty : The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Meyerbeer Libretti: Grand Opéra 1 Robert le Diable: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Liobretto for Meyerbeer's "Robert le Diable"By radamesAn excellent publication which contained many stage directions not always reproduced in the nineteenth-century vocal scores and a fine translation. Useful at a time of renewed interest in this opera at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most important and influential opera composers of the nineteenth century, enjoyed a fame during his lifetime hardly rivaled by any of his contemporaries. This eleven volume set provides in one collection all the operatic texts set by Meyerbeer in his career. The texts offer the most complete versions available. Each libretto is translated into modern English by Richard Arsenty; and each work is introduced by Robert Letellier. In this comprehensive edition of Meyerbeer's libretti, the original text and its translation are placed on facing pages for ease of use. About the AuthorRichard Arsenty, a native of the U.S. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

View of Secondary Sources, Evidence Was Inconclusive As to the Extent to Which Subject-Specific Studies Like This in Online Catalogs Had Previously Been Done

CORE SOURCES ON HARMONY AS REPRESENTED IN OHIO INSTITUTIONS: A SURVEY OF REPRESENTATIVE SOURCES FOUND IN OHIOLINK LIBRARIES ASSOCIATED WITH NASM-ACCREDITED MUSIC PROGRAMS A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Peter H. Lisius May, 2011 Thesis written by Peter H. Lisius B.A, Luther College, 1998 M.L.S., Indiana University, 2000 M.A., Kent State University, 2011 Approved by , Advisor Richard O. Devore , Director, School of Music Denise A. Seachrist , Dean, College of the Arts John R. Crawford TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………... v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………............................................................................... 1 Background of Topic Need for the Study Methodology II. SOURCES ON HARMONY…………………………………………………. 6 Classification of Sources MT50 Library of Congress Classification Other Classifications Appropriate to Harmony Historical Sources Modern Sources Historical Textbooks Modern Textbooks Sources Important to Theorists and Students of Theory III. NASM-ACCREDITED SCHOOLS IN OHIO AND THEIR MUSIC PROGRAMS……………………………………….. 18 Divisions of Schools By: Highest Degree Conferred Specific Types of Degrees Conferred Existence of a Separate Music or Performing Arts Library Association with an ARL Institution IV. ANALYSIS OF RESULTS………………………………………………… 23 Search Results Examination of Sources Searched Against OhioLINK Holding Patterns in Comparison with Categories of NASM-Accredited Schools V. RECOMMENDATIONS/CONCLUSION………………………………….. 41 Trends of Holdings in Libraries Associated with NASM-Accredited Institutions Appropriateness of OhioLINK Library Holdings Relating to Sources on Harmony Recommendations as to How Libraries in Ohio Can Better Serve Their Patrons Conclusion iii APPENDICES A. OhioLINK Libraries: Sources on Harmony in NASM-Accredited Institutions (Ashland University through the University of Mount Union)………… 48 B.