Ukraine Country Report BTI 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2017

INSIDE: l Manafort indictment welcomed in Ukraine – page 3 l Anne Applebaum at The Ukrainian Museum – page 4 l Roman Luchuk’s Carpathian landscapes at UIA – page 11 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXV No. 45 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2017 $2.00 Russian defense, intelligence companies Assassinations, abductions show Kremlin’s war targeted by new U.S. sanctions list on Ukraine extends beyond borders of Donbas by Mike Eckel ducer, VSMPO-AVISMA. U.S aircraft giant by Mark Raczkiewycz RFE/RL Boeing is a partner in that venture. The sanctions target one of Russia’s big- KYIV – A day after an Odesa-born medic WASHINGTON – The U.S. State gest and most successful industries. and sniper of Chechen heritage who fought Department has targeted more than three Reports have shown Russia is second only in the Donbas war was fatally shot, the dozen major Russian defense and intelli- to the United States in selling sophisticated Security Service of Ukraine detained the gence companies under a new U.S. sanc- arms around the world. alleged Kremlin-guided assassin of one of tions law, restricting business transactions A senior State Department official said their own high-ranking officials. with them and further ratcheting up pres- the sanctions could limit “the sale of It was the latest reminder for this war- sure against Moscow. The new list, released advanced Russian weaponry around the weary country of 42.5 million people that on October 27, came after weeks of mount- world.” the conventional battle in the easternmost ing criticism by members of Congress But the official denied that the intent of regions of the Donbas is being waged also accusing the White House of missing an the sanctions was to curb competition from nationwide asymmetrically through alleged October 1 deadline. -

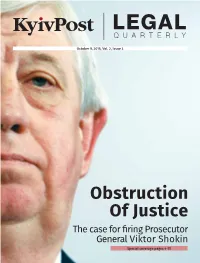

The Case for Firing Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin

October 9, 2015, Vol. 2, Issue 3 Obstruction Of Justice The case for fi ring Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin Special coverage pages 4-15 Editors’ Note Contents This seventh issue of the Legal Quarterly is devoted to three themes – or three Ps: prosecu- 4 Interview: tors, privatization, procurement. These are key areas for Ukraine’s future. Lawmaker Yegor Sobolev explains why he is leading drive In the fi rst one, prosecutors, all is not well. More than 110 lawmakers led by Yegor Sobolev to dump Shokin are calling on President Petro Poroshenko to fi re Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin. Not only has Shokin failed to prosecute high-level crime in Ukraine, but critics call him the chief ob- 7 Selective justice, lack of due structionist to justice and accuse him of tolerating corruption within his ranks. “They want process still alive in Ukraine to spearhead corruption, not fi ght it,” Sobolev said of Shokin’s team. The top prosecutor has Opinion: never agreed to be interviewed by the Kyiv Post. 10 US ambassador says prosecutors As for the second one, privatization, this refers to the 3,000 state-owned enterprises that sabotaging fi ght against continue to bleed money – more than $5 billion alone last year – through mismanagement corruption in Ukraine and corruption. But large-scale privatization is not likely to happen soon, at least until a new law on privatization is passed by parliament. The aim is to have public, transparent, compet- 12 Interview: itive tenders – not just televised ones. The law, reformers say, needs to prevent current state Shabunin says Poroshenko directors from looting companies that are sold and ensure both state and investor rights. -

Country Fact Sheet, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Country Fact Sheet DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO April 2007 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 2. POLITICAL BACKGROUND 3. POLITICAL PARTIES 4. ARMED GROUPS AND OTHER NON-STATE ACTORS 5. FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS ENDNOTES REFERENCES 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) Geography The Democratic Republic of the Congo is located in Central Africa. It borders the Central African Republic and Sudan to the north; Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Tanzania to the east; Zambia and Angola to the south; and the Republic of the Congo to the northwest. The country has access to the 1 of 26 9/16/2013 4:16 PM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/Country Fact... Atlantic Ocean through the mouth of the Congo River in the west. The total area of the DRC is 2,345,410 km². -

Ukrainska Parlamentsvalet Eviga Krig S36

NR 2 2019 FÖR FRED PÅ JORDEN OCH FRED MED JORDEN I detta nummer: 1. Dags för samarbete mot Aurora 2020 s2 2. Hibakusha protesterar mot Sveriges svek i kärnvapenfrågan och arbetar för miljö och fred. s3-5 3. Soros och Tema 16 sidor: Kochs nya - initiativ mot Ukrainska parlamentsvalet eviga krig s36 Adjö Porosjenko och s9-24 ukrainsk liberalism? FRED MÄNSKLIGA MÄNSKLIGA MILJÖ&FRED EKONOMI FRED EUROPA RÄTTIGHETER RÄTTIGHETER Sveiges Strategi för Minskad Fredsutspel i Vart är Europa humanitära Solidaritet från TV dokumentär miljö, fred och handel med Ukraina och på väg? röst har tystnat USA till Don- stoppas efter solidaritet. Läs Rysslands Minskavtalet. Ny ebok med säger IKFF bass med offren granatattack om Malmö Eu- sänkte BNP kritik av EU:s och Läkare för attacken på mot ukrainskt ropean Forum 10 procent. militarisering mot kärnvapen fackförenings- mediebolag. och deklara- och utveck- efter nej till huset i Odessa tionen antagen lingsmodell. kärnvapenavtal 2 maj 2014. på mötet s31 s3 s5 s6 s25-30 s18 s34 UB Aurora 2020 ökar otryggheten och Ukraina- krigsrisken i världen bulletin- en ges ut av Sveriges val att aktivt att bli en territorium. Det finns dock lägsna militära kapacitet ska Aktivister för spjutspets i hybridkriget mot stor anledning att anta att flera kunna komma allt snabbare och fred med hjälp Västs fiender i öst och syd har länder inom NATO kommer att närmare Rysslands gränser. skapat självförvållade problem bjudas in och att flera av dom av frivilliga Från att vara en pådrivande och terror mot andra. Flyk- deltar. krafter. kraft bakom kärnvapennedrust- tingströmmarna ökar efter vårt Sverige gör sig alltmer till en ning byter vi nu sida och låter deltagande i bombkriget mot Ukrainabul- spjutspets för militarisering Natoanpassningen styra oss Libyen och vårt deltagande i letinen kan du av vårt samhälle medan vi bort från ett halvsekel av arbete ockupationen av Afghanistan hjälpa till att tar avstånd från tidigare vilja för avskaffandet av detta hot skapar liknande problem. -

The Choice of the Regions

#11 (93) November 2015 The analysis The role of micro-business How Ukrainians are coming of local elections in Ukraine's economy to terms with the Holodomor THE CHOICE OF THE REGIONS WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION CONTENTS | 3 BRIEFING 26 Polish Politics in a New Era: 4 Long Live Stability! What the victory of Elections as a trip to the past conservatives spells domestically and internationally 7 Hanne Severinsen on what local ECONOMICS elections show about legislation, mainstream parties and prospects of 28 Life on the Edge: the regions What is happening with FOCUS microbusiness in Ukraine today? 8 Oligarch Turf Wars. 2.0: 31 “We wouldn’t mind change ourselves” Triumph of tycoon-backed parties How the micro-merchant regionally and debut of new crowd survives independent movements 34 Algirdas Šemeta: 10 Michel Tereshchenko: "Criminal law is used “We have to clean all in business all too often" of Hlukhiv of corruption” Business ombudsman on The newly-elected mayor the government and business, on plans for the the progress of reforms and the adoption town’s economic revival of European practices in Ukraine SOCIETY 12 The More Things Stay the Same: Donbas remains the base 38 Do It Yourself: for yesterday’s Party of the Regions, How activists defend community but democratic parties interests when undemocratic forces make serious inroads control local government POLITICS 40 Karol Modzelewski "The seed of authoritarianism has sprouted 14 Tetiana Kozachenko: in the minds of Eastern -

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2019 Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann. 2021. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2019. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich. These (former) assistants have made major contributions to the dataset, without which CPDS would not exist. In chronological and descending order: Angela Odermatt, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, Sarah Engler, David Weisstanner, Panajotis Potolidis, Marlène Gerber, Philipp Leimgruber, Michelle Beyeler, and Sarah Menegal. -

How Do Ukrainians Want to End the Donbas War?

How Do Ukrainians Want to End the Donbas War? PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 555 December 2018 Mikhail Alexseev1 San Diego State University Whereas it is hard to imagine the Donbas retuning fully to Ukraine’s control without Russia ending its multi-year military and economic backing of the separatist entities there, the question of the region’s reintegration is highly prevalent in Ukraine’s political and social life. The Donbas war has been the number one concern over the last three years among Ukrainians who now also see their government’s ability to end this war as a primary issue in the run-up to the 2019 presidential elections. Opinion surveys, focus groups, and interviews across Ukraine indicate that public support across regional divides is more likely for candidates and prospective leaders who can properly articulate, and have the integrity to pursue, a balanced, multi-pronged Donbas settlement strategy that combines military buildup, selective sanctioning of separatist entities, and political negotiations. Such candidates or leaders would be more likely to attract undecided voters than those who prioritize only one resolution path. Those who articulate credible, national, socioeconomic development policies that are clearly non-contingent on, yet not prohibitive of, Donbas reintegration, have good chances of gaining public support, which in turn would advance sensible progress ending the often-deadly discord. It’s a Big Issue The Donbas war has a death toll of over 10,500, mostly due to Russia’s lethal military assistance to its client entities the Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR). -

1.1. ENG Fedorenko Two Movements.Docx

ІДЕОЛОГІЯ І ПОЛІТИКА ИДЕОЛОГИЯ И ПОЛИТИКА IDEOLOGY AND POLITICS THE TWO MOVEMENTS: LIBERALS AND NATIONALISTS DURING EUROMAIDAN Kostiantyn Fedorenko Abstract. This article offers a hypothesis that two separate yet cooperating movements, liberal and nationalist, participated in the Ukrainian protests of late 2013 – early 2014. To test this hypothesis, we define that a protest movement has its own leaders, purpose and ideology, perception of the current situation and the opponents of the movement, and tactics of action. It is found out that these factors were different for liberals and nationalists participating in the protests. The offered “two-movement approach” allows avoiding false generalizations about the protesters participating in these events, while increasing our explanatory capability. Keywords: Ukraine, Euromaidan, social movements, protest, Ukrainian nationalism, two-movement approach Introduction The winter events in Ukraine had attracted worldwide attention and international compassion towards the protesters. However, the later events in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine overshadowed the popular protests in Kyiv, as scholars directed their attention to the most recent and worrisome developments. Yet we maintain that a better understanding of the winter events, labeled “Revolution of Dignity” by the Ukrainian media (Kyiv Post 2014), is necessary in order to explain the forthcoming events – including annexation of Crimea and civil conflicts in Eastern Ukraine – as well as to be capable of making knowledgeable prognoses for the events that are yet to come in the region. As will be shown in the next sections, some speakers attempted to extend either liberal or nationalist logic of thinking to the protesters in general, either stating that they championed for their individual rights or describing them as “nationalist” and “Banderite”. -

Turkey's Evolving Dynamics

Turkey’s Evolving Dynamics CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & Strategic Choices for U.S.-Turkey Relations CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1800 K Street | Washington, DC 20006 director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Stephen J. Flanagan E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org deputy director Samuel J. Brannen principal authors Bulent Aliriza Edward C. Chow Andrew C. Kuchins Haim Malka Julianne Smith contributing authors Ian Lesser Eric Palomaa Alexandros Petersen research coordinator Kaley Levitt March 2009 ISBN 978-0-89206-576-9 Final Report of the CSIS U.S.-Turkey Strategic Initiative CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & Ë|xHSKITCy065769zv*:+:!:+:! Türk-Amerikan Stratejik Girisimi¸ CSIS INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Turkey’s Evolving Dynamics Strategic Choices for U.S.-Turkey Relations DIRECTOR Stephen J. Flanagan DEPUTY DIRECTOR Samuel J. Brannen PRINCIPAL AUTHORS Bulent Aliriza Edward C. Chow Andrew C. Kuchins Haim Malka Julianne Smith CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS Ian Lesser Eric Palomaa Alexandros Petersen RESEARCH COORDINATOR Kaley Levitt March 2009 Final Report of the CSIS U.S.-Turkey Strategic Initiative Türk-Amerikan Stratejik Girisimi¸ About CSIS In an era of ever-changing global opportunities and challenges, the Center for Strategic and Inter- national Studies (CSIS) provides strategic insights and practical policy solutions to decisionmak- ers. CSIS conducts research and analysis and develops policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke at the height of the Cold War, CSIS was dedicated to the simple but urgent goal of finding ways for America to survive as a nation and prosper as a people. Since 1962, CSIS has grown to become one of the world’s preeminent public policy institutions. -

The Kremlin's Economic Checkmate Maneuver

fmso.leavenworth.army.mil/oewatch Vol. 5 Issue #01 January 2015 Foreign Military Studies Office OEWATCH FOREIGN NEWS & PERSPECTIVES OF THE OPERATIONAL ENVIRONMENT RUSSIA Special Feature: The Kremlin’s Economic Checkmate Maneuver SPECIAL ESSAY LATIN AMERICA CENTRAL ASIA 75 The Kremlin’s Economic Checkmate Maneuver 22 Can Guerrillas be Defeated? 45 The State of Uzbekistan’s Armed Forces 23 How to End the Drug War 46 Incidents of Violence on Kyrgyzstan’s Borders: TURKEY 25 How the Neighbors See Venezuela A Year in Review 3 Realpolitik Drives Turkish-Russian Relations 26 Drones in Venezuela 47 What the Islamic State means for Central Asia 5 The Turkish Navy’s Operational Environment 27 The Proliferation of Narco Taxis 49 Islamic State Features Kazakh Kids in Syria and Vision in Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Guerrero 7 Turkish Army 2020 28 Social Media: The Impetus of Change behind RUSSIA Narco Communications in Mexico 50 Combat Robot Companies Enter the Table of MIDDLE EAST 29 11 Year-Old-Girl May be the Youngest Drug Mule Organization and Equipment 9 Supreme Leader Says America behind Ever Arrested by Authorities in Colombia 52 New Ground Forces Field Manuals Islamic Sectarianism, Radicalism May Better Align Tactics to Doctrine 10 Iran Expands Its Strategic Borders INDO-PACIFIC ASIA 54 Russia Touts Roles, Capabilities, and Possible 11 Supreme Leader Speaks to Graduating Army 30 Vanuatu: A Tiny Island Nation Can Create Ripples Targets for the Iskander Cadets 32 Maoist Insurgence in Modi’s India 56 The Future of Russian Force Projection: 12 The