1.1. ENG Fedorenko Two Movements.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukraine Media Assessment and Program Recommendations

UKRAINE MEDIA ASSESSMENT AND PROGRAM RECOMMENDATIONS VOLUME I FINAL REPORT June 2001 USAID Contract: AEP –I-00-00-00-00018-00 Management Systems International (MSI) Programme in Comparative Media Law & Policy, Oxford University Consultants: Dennis M. Chandler Daniel De Luce Elizabeth Tucker MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL 600 Water Street, S.W. 202/484-7170 Washington, D.C. 20024 Fax: 202/488-0754 USA TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I Acronyms and Glossary.................................................................................................................iii I. Executive Summary............................................................................................................... 1 II. Approach and Methodology .................................................................................................. 6 III. Findings.................................................................................................................................. 7 A. Overall Media Environment............................................................................................7 B. Print Media....................................................................................................................11 C. Broadcast Media............................................................................................................17 D. Internet...........................................................................................................................25 E. Business Practices .........................................................................................................26 -

Kremlin-Linked Forces in Ukraine's 2019 Elections

Études de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Reports 25 KREMLIN-LINKED FORCES IN UKRAINE’S 2019 ELECTIONS On the Brink of Revenge? Vladislav INOZEMTSEV February 2019 Russia/NIS Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36567-981-7 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2019 How to quote this document: Vladislav Inozemtsev, “Kremlin-Linked Forces in Ukraine’s 2019 Elections: On the Brink of Revenge?”, Russie.NEI.Reports, No. 25, Ifri, February 2019. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15—FRANCE Tel. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00—Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Dr Vladislav Inozemtsev (b. 1968) is a Russian economist and political researcher since 1999, with a PhD in Economics. In 1996 he founded the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies and has been its Director ever since. In recent years, he served as Senior or Visiting Fellow with the Institut fur die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna, with the Polski Instytut Studiów Zaawansowanych in Warsaw, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik in Berlin, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Johns Hopkins University in Washington. -

Ukraine Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Ukraine This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Ukraine. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Ukraine 3 Key Indicators Population M 45.0 HDI 0.743 GDP p.c., PPP $ 8272 Pop. growth1 % p.a. -0.3 HDI rank of 188 84 Gini Index 25.5 Life expectancy years 71.2 UN Education Index 0.825 Poverty3 % 0.5 Urban population % 69.9 Gender inequality2 0.284 Aid per capita $ 32.3 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary The period under review can be characterized by three major trends. -

The Struggle for Ukraine

Chatham House Report Timothy Ash, Janet Gunn, John Lough, Orysia Lutsevych, James Nixey, James Sherr and Kataryna Wolczuk The Struggle for Ukraine Chatham House Report Timothy Ash, Janet Gunn, John Lough, Orysia Lutsevych, James Nixey, James Sherr and Kataryna Wolczuk Russia and Eurasia Programme | October 2017 The Struggle for Ukraine The Royal Institute of International Affairs Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 Copyright © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2017 Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author(s). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. ISBN 978 1 78413 243 9 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend. The material selected for the printing of this report is manufactured from 100% genuine de-inked post-consumer waste by an ISO 14001 certified mill and is Process Chlorine Free. Typeset by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Cover image: A banner marking the first anniversary of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea is hung during a plenary session of Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, in Kyiv on 6 March 2015. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2017

INSIDE: l Manafort indictment welcomed in Ukraine – page 3 l Anne Applebaum at The Ukrainian Museum – page 4 l Roman Luchuk’s Carpathian landscapes at UIA – page 11 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXV No. 45 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2017 $2.00 Russian defense, intelligence companies Assassinations, abductions show Kremlin’s war targeted by new U.S. sanctions list on Ukraine extends beyond borders of Donbas by Mike Eckel ducer, VSMPO-AVISMA. U.S aircraft giant by Mark Raczkiewycz RFE/RL Boeing is a partner in that venture. The sanctions target one of Russia’s big- KYIV – A day after an Odesa-born medic WASHINGTON – The U.S. State gest and most successful industries. and sniper of Chechen heritage who fought Department has targeted more than three Reports have shown Russia is second only in the Donbas war was fatally shot, the dozen major Russian defense and intelli- to the United States in selling sophisticated Security Service of Ukraine detained the gence companies under a new U.S. sanc- arms around the world. alleged Kremlin-guided assassin of one of tions law, restricting business transactions A senior State Department official said their own high-ranking officials. with them and further ratcheting up pres- the sanctions could limit “the sale of It was the latest reminder for this war- sure against Moscow. The new list, released advanced Russian weaponry around the weary country of 42.5 million people that on October 27, came after weeks of mount- world.” the conventional battle in the easternmost ing criticism by members of Congress But the official denied that the intent of regions of the Donbas is being waged also accusing the White House of missing an the sanctions was to curb competition from nationwide asymmetrically through alleged October 1 deadline. -

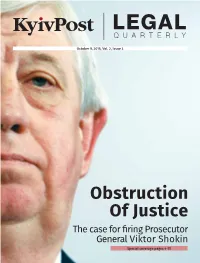

The Case for Firing Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin

October 9, 2015, Vol. 2, Issue 3 Obstruction Of Justice The case for fi ring Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin Special coverage pages 4-15 Editors’ Note Contents This seventh issue of the Legal Quarterly is devoted to three themes – or three Ps: prosecu- 4 Interview: tors, privatization, procurement. These are key areas for Ukraine’s future. Lawmaker Yegor Sobolev explains why he is leading drive In the fi rst one, prosecutors, all is not well. More than 110 lawmakers led by Yegor Sobolev to dump Shokin are calling on President Petro Poroshenko to fi re Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin. Not only has Shokin failed to prosecute high-level crime in Ukraine, but critics call him the chief ob- 7 Selective justice, lack of due structionist to justice and accuse him of tolerating corruption within his ranks. “They want process still alive in Ukraine to spearhead corruption, not fi ght it,” Sobolev said of Shokin’s team. The top prosecutor has Opinion: never agreed to be interviewed by the Kyiv Post. 10 US ambassador says prosecutors As for the second one, privatization, this refers to the 3,000 state-owned enterprises that sabotaging fi ght against continue to bleed money – more than $5 billion alone last year – through mismanagement corruption in Ukraine and corruption. But large-scale privatization is not likely to happen soon, at least until a new law on privatization is passed by parliament. The aim is to have public, transparent, compet- 12 Interview: itive tenders – not just televised ones. The law, reformers say, needs to prevent current state Shabunin says Poroshenko directors from looting companies that are sold and ensure both state and investor rights. -

Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine

Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine September 14 – October 10, 2017 Methodology National Sample • The survey was conducted by GfK Ukraine on behalf of the Center for Insights in Survey Research. • The survey was conducted throughout Ukraine (except for the occupied territories of Crimea and the Donbas) from September 14 to October 10, 2017 through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 2,400 permanent residents of Ukraine aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by gender, age, region, and settlement size. An additional 4,800 respondents were also surveyed in the cities of Dnipro, Khmelnytskyi, Mariupol and Mykolaiv (i.e. 1,200 respondents in each city). A multi-stage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday methods for respondent selection. • Stage One: The territory of Ukraine was split into 25 administrative regions (24 regions of Ukraine and Kyiv). The survey was conducted throughout all regions of Ukraine, with the exception of the occupied territories of Crimea and the Donbas. • Stage Two: The selection of settlements was based on towns and villages. Towns were grouped into subtypes according to their size: • Cities with a population of more than 1 million • Cities with a population of between 500,000-999,000 • Cities with a population of between 100,000-499,000 • Cities with a population of between 50,000-99,000 • Cities with a population up to 50,000 • Villages Cities and villages were selected at random. The number of selected cities/villages in each of the regions is proportional to the share of population living in cities/villages of a certain type in each region. -

Ukraine Local Elections, 25 October 2015

ELECTION OBSERVATION DELEGATION TO THE LOCAL ELECTIONS IN UKRAINE (25 October 2015) Report by Andrej PLENKOVIĆ, ChaIr of the Delegation Annexes: A - List of Participants B - EP Delegation press statement C - IEOM Preliminary Findings and Conclusions on 1st round and on 2nd round 1 IntroductIon On 10 September 2015, the Conference of Presidents authorised the sending of an Election Observation Delegation, composed of 7 members, to observe the local elections in Ukraine scheduled for 25 October 2015. The Election Observation Delegation was composed of Andrej Plenkovič (EPP, Croatia), Anna Maria Corazza Bildt (EPP, Sweden), Tonino Picula (S&D, Croatia), Clare Moody (S&D, United Kingdom), Jussi Halla-aho (ECR, Finland), Kaja Kallas (ALDE, Estonia) and Miloslav Ransdorf (GUE, Czech Republic). It conducted its activities in Ukraine between 23 and 26 October, and was integrated in the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) organised by ODIHR, together with the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. On election-day, members were deployed in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa and Dnipropetrovsk. Programme of the DelegatIon In the framework of the International Election Observation Mission, the EP Delegation cooperated with the Delegation of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities, headed by Ms Gudrun Mosler-Törnström (Austria), while the OSCE/ODIHR long-term Election Observation Mission headed by Tana de Zulueta (Italy). The cooperation with the OSCE/ODIHR and the Congress went as usual and a compromise on the joint statement was reached (see annex B). Due to the fact that only two parliamentary delegations were present to observe the local elections, and had rather different expectations as regards meetings to be organised, it was agreed between all parties to limit the joint programme to a briefing by the core team of the OSCE/ODIHR. -

Ukrainska Parlamentsvalet Eviga Krig S36

NR 2 2019 FÖR FRED PÅ JORDEN OCH FRED MED JORDEN I detta nummer: 1. Dags för samarbete mot Aurora 2020 s2 2. Hibakusha protesterar mot Sveriges svek i kärnvapenfrågan och arbetar för miljö och fred. s3-5 3. Soros och Tema 16 sidor: Kochs nya - initiativ mot Ukrainska parlamentsvalet eviga krig s36 Adjö Porosjenko och s9-24 ukrainsk liberalism? FRED MÄNSKLIGA MÄNSKLIGA MILJÖ&FRED EKONOMI FRED EUROPA RÄTTIGHETER RÄTTIGHETER Sveiges Strategi för Minskad Fredsutspel i Vart är Europa humanitära Solidaritet från TV dokumentär miljö, fred och handel med Ukraina och på väg? röst har tystnat USA till Don- stoppas efter solidaritet. Läs Rysslands Minskavtalet. Ny ebok med säger IKFF bass med offren granatattack om Malmö Eu- sänkte BNP kritik av EU:s och Läkare för attacken på mot ukrainskt ropean Forum 10 procent. militarisering mot kärnvapen fackförenings- mediebolag. och deklara- och utveck- efter nej till huset i Odessa tionen antagen lingsmodell. kärnvapenavtal 2 maj 2014. på mötet s31 s3 s5 s6 s25-30 s18 s34 UB Aurora 2020 ökar otryggheten och Ukraina- krigsrisken i världen bulletin- en ges ut av Sveriges val att aktivt att bli en territorium. Det finns dock lägsna militära kapacitet ska Aktivister för spjutspets i hybridkriget mot stor anledning att anta att flera kunna komma allt snabbare och fred med hjälp Västs fiender i öst och syd har länder inom NATO kommer att närmare Rysslands gränser. skapat självförvållade problem bjudas in och att flera av dom av frivilliga Från att vara en pådrivande och terror mot andra. Flyk- deltar. krafter. kraft bakom kärnvapennedrust- tingströmmarna ökar efter vårt Sverige gör sig alltmer till en ning byter vi nu sida och låter deltagande i bombkriget mot Ukrainabul- spjutspets för militarisering Natoanpassningen styra oss Libyen och vårt deltagande i letinen kan du av vårt samhälle medan vi bort från ett halvsekel av arbete ockupationen av Afghanistan hjälpa till att tar avstånd från tidigare vilja för avskaffandet av detta hot skapar liknande problem. -

The Choice of the Regions

#11 (93) November 2015 The analysis The role of micro-business How Ukrainians are coming of local elections in Ukraine's economy to terms with the Holodomor THE CHOICE OF THE REGIONS WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION CONTENTS | 3 BRIEFING 26 Polish Politics in a New Era: 4 Long Live Stability! What the victory of Elections as a trip to the past conservatives spells domestically and internationally 7 Hanne Severinsen on what local ECONOMICS elections show about legislation, mainstream parties and prospects of 28 Life on the Edge: the regions What is happening with FOCUS microbusiness in Ukraine today? 8 Oligarch Turf Wars. 2.0: 31 “We wouldn’t mind change ourselves” Triumph of tycoon-backed parties How the micro-merchant regionally and debut of new crowd survives independent movements 34 Algirdas Šemeta: 10 Michel Tereshchenko: "Criminal law is used “We have to clean all in business all too often" of Hlukhiv of corruption” Business ombudsman on The newly-elected mayor the government and business, on plans for the the progress of reforms and the adoption town’s economic revival of European practices in Ukraine SOCIETY 12 The More Things Stay the Same: Donbas remains the base 38 Do It Yourself: for yesterday’s Party of the Regions, How activists defend community but democratic parties interests when undemocratic forces make serious inroads control local government POLITICS 40 Karol Modzelewski "The seed of authoritarianism has sprouted 14 Tetiana Kozachenko: in the minds of Eastern -

Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2019 Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis Nicholas Pehlman The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3073 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © Copyright by Nick Pehlman, 2018 All rights reserved ii Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional Crisis by Nicholas Pehlman This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date Mark Ungar Chair of Examining Committee Date Alyson Cole Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Julie George Jillian Schwedler THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Police Reform in Ukraine Since the Euromaidan: Police Reform in Transition and Institutional -

Administrative Reform and Local Elections in Ukraine 2020

Administrative Reform and Local Elections in Ukraine 2020 By ECEAP Senior Research Fellow Aap Neljas ABSTRACT 2020 has been an important year for Ukrainian local politics. Firstly, administrative reform has introduced a new strengthened and decentralised administrative division of the country, with the goal of strengthening local self-government. Also as a result of new administrative division, the country now also has new electoral districts for local elections that will for the first time be mostly conducted according to a proportional party list system. Secondly, it is a year of the local elections on 25 October 2020, elections that follow triumph of the Servant of the People party in presidential and parliamentary elections, which delivered a strong mandate for the president and a majority in parlament. Therefore elections are not only important for local decisionmaking, but will also be an indicator of the real support for President Zelenskyy and his Servant of the People party. Recent public opinion polls show that in general Ukrainians support mainly established national political parties that have representation also in country’s Parliament. The ruling Servant of the People Party has clear lead overall, followed by main pro-Russian opposition party Opposition Platform – For Life and two pro-European opposition parties European Solidarity and Batkivshchyna. At the same time, it is probable, that in many big cities parties led by popular local politicians prevail. It is therefore expected that that the national parties, especially ruling Servant of the People party, are dependent on cooperation and the formation of coalitions with other national and also with local parties.