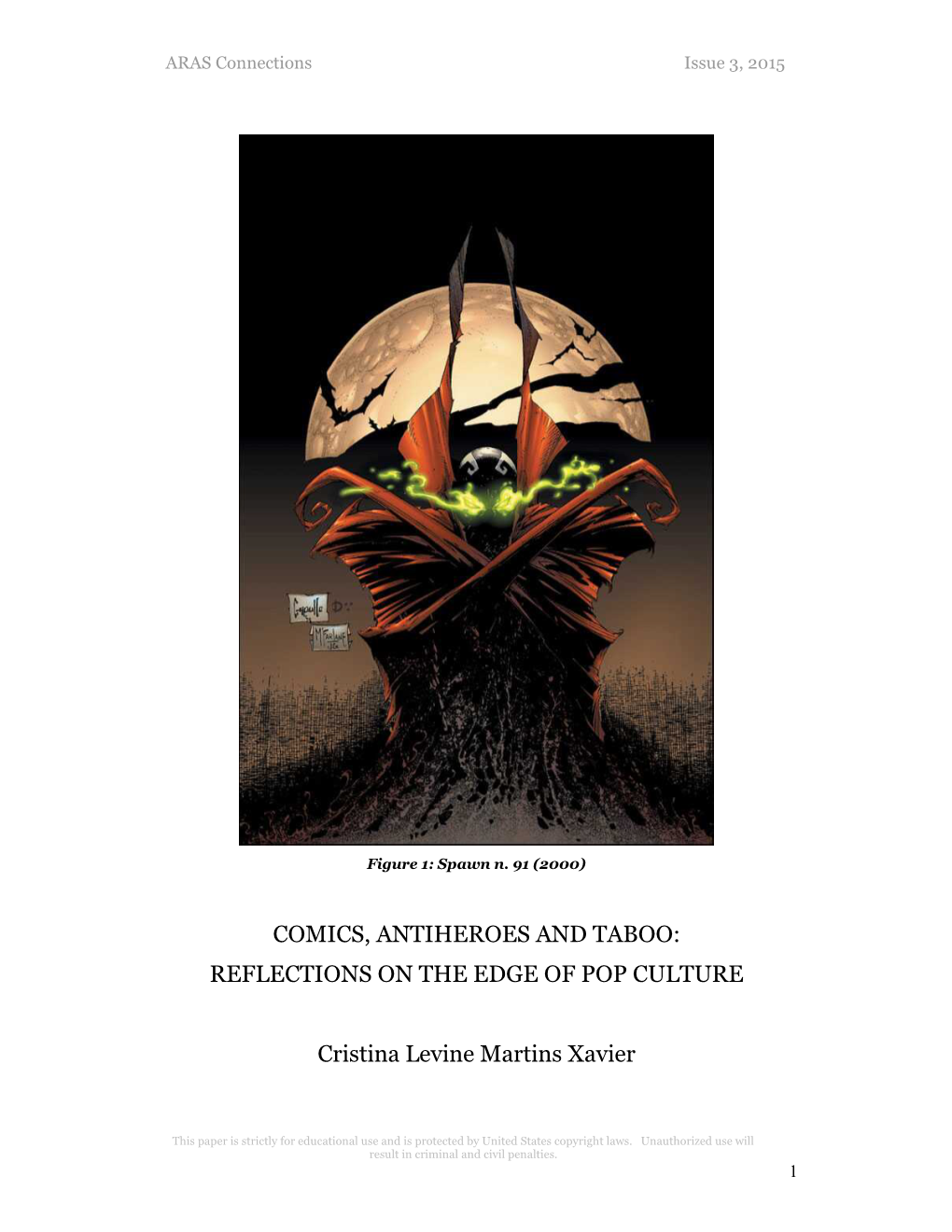

Comics, Antiheroes and Taboo: Reflections on the Edge of Pop Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Exploring the Procedural Rhetoric of a Black Lives Matter-Themed Newsgame

Special Issue: Gamifying News Convergence: The International Journal of Research into Endless mode: New Media Technologies 1–13 ª The Author(s) 2020 Exploring the procedural Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions rhetoric of a Black Lives DOI: 10.1177/1354856520918072 Matter-themed newsgame journals.sagepub.com/home/con Allissa V Richardson University of Southern California, USA Abstract A week after the back-to-back police shootings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling in early July 2016, a game developer, who goes by the screen name Yvvy, sat in front of her console mulling over the headlines. She designed a newsgame that featured civilian–police interactions that were plucked from that reportage. She entitled it Easy Level Life. The newsgame is fashioned in what developers call ‘endless mode’, where players are challenged to last as long as possible against a continuing threat, with limited resources or player-character lives. This case study explores the procedural rhetoric of Easy Level Life to investigate how it condemns police brutality through play. Using Teun van Dijk’s concept of ‘news as discourse’ as the framework, I found that this newsgame followed the narrative structure of a traditional newspaper editorial very closely. I explain how the situation–evaluation–conclusion discursive model best describes how Easy Level Life conveys its political ideologies. I conclude by suggesting that this discursive model should perhaps become a benchmarking tool for future newsgame developers who aim to strengthen their arguments for social justice. Keywords Black Lives Matter, discourse analysis, journalism, newsgames, procedural rhetoric, race, social justice Introduction It was a simple request. -

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan

Queer Here: Poetry to Comic Emma Lennen Katie Jan Pull Quote: “For the new audience of queer teenagers, the difference between the public and the superhero resonates with them because they feel different from the rest of society.” Consider this: a superhero webcomic. Now consider this: a queer superhero webcomic. If you are anything like me, you were infinitely more elated at the second choice, despite how much you enjoy the first. I love reading queer webcomics because by being online, they bypass publishers who may shoot them down for their queerness. As a result, they manage to elude the systematic repression of the LGBTQA+ community. In the 1950s, when repression of the community was even more prevalent, Frank O’Hara wrote the poem “Homosexuality” to express his journey of acceptance as well as to give advice to future gay people. The changes I made in my translation of the poem “Homosexuality” into a modern webcomic demonstrate the different time periods’ expectations of queer content, while still telling the same story with the same purpose, just in a different genre. Despite the difference between the genres, the first two lines and the copious amount of imagery present in the poem allowed for some near-direct translation. The poem begins with “So we are taking off our masks, are we, and keeping / our mouths shut? As if we’d been pierced by a glance!” (O’Hara 1-2). While usually masks symbolize hiding your true self and therefore have a negative connotation, the poem instead considers it one’s pride. Similarly, for many superheroes, the mask does not represent shame, it represents power and responsibility. -

Spawn: the Eternal Prelude Darkness

Spawn: The Eternal Prelude Darkness. Pain. What . oh. Oh god. I'm alive! CHOOSE. What? Oh great God almighty in Heaven . NOT QUITE. CHOOSE. Choose . choose what? What are you? Where am I? Am I in Hell? NOT YET. DO YOU WISH TO RETURN? Yes! Yes, of course I want to go back! But . what's the catch? What is all this? IT IS NONE OF YOUR CONCERN. WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE FOR A RETURN? TO SEE YOUR LOVED ONES, TO ONCE MORE TASTE LIFE? WHAT WOULD YOU GIVE? I . I'm dead, aren't I? YES. But . what can I give? I am dead, so I have nothing! NOT TRUE. YOU HAVE YOURSELF. Myself? I don't understand . is it my soul you want? NO. I ALREADY HOLD YOUR SOUL . I WISH TO KNOW IF YOU WOULD SERVE ME WILLINGLY IN RETURN FOR COMING BACK. Serve . to see my wife again . yes . to hold my children once more . yes. I will serve you. VERY WELL. THE DEAL IS DONE . In a rainy graveyard, something fell smoking to the ground. It sat up, shaking its head, looking around itself. Strange. Why was he lying here? He tried to stand up, surprising himself by leaping at least twenty feet into the air, landing as smoothly as a cat. How . then something caught his attention. He stared into the puddle of rainwater, trying to discern the vague shape that must be his own face. And then he screamed. Because what stared back was the burn-scarred skullface of a corpse, its eyes glowing a deep green. -

Immortals' Realm

EpicMail presents Immortals’ Realm Version 2.2 Legends II Module First published 1990 in the USA. EpicMail is an Official Licensee, all Legends copyrighted material by Midnight Games, provided with permission. Initial concept and design by Bill Combs, Reagan Schaupp and Scott Bargelt. Reworked in August 2002 Reworked and expanded (Version 2.0) by Jens-Uwe Rüsse, Harald Gehringer, Herwig Dobernigg, Markus Freystätter, Klaus Bachler and Johannes Klapf. Graphics by Danny Willis. Game map by Herwig Bachler. Downloadable map can be found at: www.harlequingames.com Legends II Game System TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 OVERVIEW.......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 SETUP RULES ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 HISTORY OF VERANA ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 FACTIONS......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Invincible Jumpchain- Compliant CYOA

Invincible Jumpchain- Compliant CYOA By Lord Statera Introduction Welcome to Invincible. Set in the Image comic book multiverse, this setting is home to older heroes and villains like Spawn, The Darkness, and The Witchblade. This story, however, focuses on the new superhero Invincible (Mark Grayson), the half-breed Viltrumite-Human hybrid and son of the world famous hero Omni-Man (Nolan Grayson). Invincible spends the beginning of his career working alongside the Teen Team, and with his father, to defend not only Baltimore but the Earth from many and varied threats. Little does he know that his father, rather than being an alien from a peace loving species, is actually a harbinger of war to the planet Earth. Viltrumites are actually a race bent on conquering the universe, one planet at a time. And with their level of power, not much can stop them. Fortunately, there is one secret the Viltrumite Empire has been hiding. Over 99% of the Viltrumite population had been wiped out using a plague genetically engineered by scientists of the Coalition of Planets, they are forced to wage a proxy war using their servant races against the Coalition, all the while sending individual Viltrumites out to take one world at a time, in their attempt to conquer the stars. As humans are the closest genetic match for the Viltrumite race outside of another Viltrumite, the remnants of this mighty alien race turn their sights on Earth in the hopes of using it as a breeding farm to repopulate their race. To help you survive in this universe, here are 1000 Choice Points. -

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

Book of Immortals: Disciple: Volume 1 (An Antagonist's Story, Alternative Reality, Antihero Fantasy) Online

YoFxL [Pdf free] Book of Immortals: Disciple: Volume 1 (An antagonist's story, alternative reality, antihero fantasy) Online [YoFxL.ebook] Book of Immortals: Disciple: Volume 1 (An antagonist's story, alternative reality, antihero fantasy) Pdf Free Kassandra Lynn ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #88104 in eBooks 2014-08-23 2014-08-23File Name: B00MZYS8ZS | File size: 44.Mb Kassandra Lynn : Book of Immortals: Disciple: Volume 1 (An antagonist's story, alternative reality, antihero fantasy) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Book of Immortals: Disciple: Volume 1 (An antagonist's story, alternative reality, antihero fantasy): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. WowBy Jasmine RobersonI absolutely loved this story! It threw me through quite a few loops at first and it really brought me home and touched my heart and soul. I love this book! And I love how it's not about the main protagonist, the protagonist of this story is actually a side character which made it even more interesting cause then you get someone else's story and root for them instead of the actual lucky protagonist who seemed to be more of a spy than anything. Told my friends about this book too. I'm going to buy the next one and start it asap!0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Love the storyline and the character developmentBy NicLawUnlike many of the other reviewers here, I did not receive a free copy of this book in exchange for writing an honest review. -

A Genealogy of Antihero∗

A GENEALOGY OF ANTIHERO∗ Murat KADİROĞLU∗∗ Abstract “Antihero”, as a literary term, entered literature in the nineteenth century with Dostoevsky, and its usage flourished in the second half of the twentieth century. However, the antihero protagonists or characters have been on stage since the early Greek drama and their stories are often told in the works of the twentieth century literature. The notion of “hero” sets the base for “antihero”. In every century, there are heroes peculiar to their time; meanwhile, antiheroes continue to live as well, though not as abundant as heroes in number. The gap between them in terms of their personality, moral code and value judgements is very obvious in their early presentation; however, the closer we come to our age, the vaguer this difference becomes. In contemporary literature, antiheroes have begun to outnumber heroes as a result of historical, political and sociological facts such as wars, and literary pieces have tended to present themes of failure, inaction, uncertainty and despair rather than heroism and valour. This study argues that Second World War has the crucial impact on the development of the notion of modern antihero. As a consequence of the war, “hero” as the symbol of valour, adventure, change and action in the legends and epic poems has been transformed into “antihero” of failure and despair, especially in realist, absurdist and existentialist works written during/after the Second World War. Keywords: Antihero, Hero, Heroism, Protagonist, Romantic Hero, Second World War, Post-war Öz Anti-kahramanın Soykütüğü Edebi bir terim olarak “anti-kahraman” ya da “karşı-kahraman”, on dokuzuncu yüzyılda Dostoyevski ile edebiyata girmiştir ve kullanımı yirminci yüzyılın ikinci yarısında doruğa ulaşmıştır. -

Graphic Evangelism 1

Running head: GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 1 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Mark Cupp A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Edward Edman, MFA Thesis Chair ______________________________ Chris Gaumer, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Ronald Sumner, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 3 Abstract This thesis explores the use of mainstream graphic novels as a means of Christian evangelism. Though not exclusively Christian, the graphic novel, The Beast Within, will educate its target audience by using attractive illustrations, relatable issues, and understandable morals in a fictional, biblically inspired story. This thesis will include character designs, artwork, chapter summaries, and a single chapter of a self-written, self- illustrated graphic novel along with a short summary of Christian references and symbols. The novel will follow six half-human, half-animal warriors on their adventure to restore the balance of their world, which has been disrupted by a powerful enemy. GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 4 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Introduction As recorded in Matthew 28:16-20, all Christians are commanded by Christ to spread the Gospel to all corners of the earth. Many believers almost immediately equate evangelism to Sunday morning services, church mission trips, or distribution of witty, ever-popular salvation tracts; however, Jesus utilized other methods to teach His people, such as telling simple stories and using familiar images and illustrations. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Egyptian Literature

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Egyptian Literature This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Egyptian Literature Release Date: March 8, 2009 [Ebook 28282] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EGYPTIAN LITERATURE*** Egyptian Literature Comprising Egyptian Tales, Hymns, Litanies, Invocations, The Book Of The Dead, And Cuneiform Writings Edited And With A Special Introduction By Epiphanius Wilson, A.M. New York And London The Co-Operative Publication Society Copyright, 1901 The Colonial Press Contents Special Introduction. 2 The Book Of The Dead . 7 A Hymn To The Setting Sun . 7 Hymn And Litany To Osiris . 8 Litany . 9 Hymn To R ....................... 11 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 15 Hymn To The Setting Sun . 19 The Chapter Of The Chaplet Of Victory . 20 The Chapter Of The Victory Over Enemies. 22 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To The Overseer . 24 The Chapter Of Giving A Mouth To Osiris Ani . 24 Opening The Mouth Of Osiris . 25 The Chapter Of Bringing Charms To Osiris . 26 The Chapter Of Memory . 26 The Chapter Of Giving A Heart To Osiris . 27 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 28 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 29 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Chapter Of Preserving The Heart . 30 The Heart Of Carnelian . 31 Preserving The Heart . 31 Preserving The Heart .