Border Intimacies: Student Activism, Reproductive Justice, and Queer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Joya I.S.D

What it takes to take AP courses For more information Character Contact your child’s counselor: Curiosity, creativity and commitment are key ingredients for success in AP courses. Academic Preparation You don't need to be top of your class to be an AP student, La Joya High School but you'll want to be prepared for the AP course you 580-5100 choose. Motivation You show your determination when you do the things that Palmview High School matter to you 519-5779 Grading System The process and standards for setting AP Juarez Lincoln High School grades remain the same so that the merit of 519-4150 AP grades is consistent over time. Each exam is scored on the following five-point scale: 5 - EXTREMELY WELL QUALIFIED Jimmy Carter Early College High School 4 - WELL QUALIFIED 584-4842 3 - QUALIFIED 2 - POSSIBLY QUALIFIED 1 - NO RECOMMENDATION Thelma R. Salinas Early College High School La Joya I.S.D. 580-5908 What are AP courses Like Advanced Academic Services AP courses typically demand more of students than regular or honors courses. Advanced Placement Courses Classes tend to be fast-paced and cover more material than typi- cal high school classes. Parent Information More time, inside and outside of the classroom, is required to complete lessons, assignments and homework. AP teachers expect their students to think critically, analyze and The Benefits of AP Courses synthesize facts and data, weigh competing perspectives, and write clearly and persuasively. Results AP courses can be challenging, but it’s are sent to each student’s home, high school and designated col- work that pays off. -

FORALL12-13 Proof Read

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331998586 FOR ALL: The Sustainable Development Goals and LGBTI People Research · February 2019 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.23989.73447 CITATIONS READS 0 139 2 authors: Andrew Park Lucas Ramón Mendos University of California, Los Angeles University of California, Los Angeles 17 PUBLICATIONS 6 CITATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Gender Identity and Expression View project LGBTI and international development View project All content following this page was uploaded by Andrew Park on 26 March 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. FOR ALL The Sustainable Development Goals and LGBTI People “We pledge that no one will be left behind…. [T]he Goals and targets must be met for all nations and peoples and for all segments of society.” United Nations General Assembly. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. PREFACE This report was produced pursuant to a consultation contract (2018-05 RAP/SDGs) issued by RFSL Forbundeẗ (Org nr: 802011-9353). This report was authored by Andrew Park and Lucas Ramon Mendos. The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and may not necessarily reflect those of RFSL. Micah Grzywnowicz, RFSL International Advocacy Advisor, contributed to the shaping, editing, and final review of this report. Winston Luhur, Research Assistant, Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, contributed to research which has been integrated into this publication. Ilan Meyer, Ph.D., Williams Distinguished Senior Scholar for Public Policy, Williams Institute at UCLA’s School of Law, Elizabeth Saewyc, Director and Professor at the University of British Columbia School of Nursing, and Carmen Logie, Assistant Professor at Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto, provided expert guidance to the authors. -

Request for Proposals

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS Date: July 5, 2018 Proposal Category: School Nutrition Program Food Safety and Sanitation Product and Services Proposal Number: 19-AGENCY-000055 The Region One Education Service Center is soliciting request for proposals from firms (“Respondents”) for the selection of School Nutrition Program Food Safety and Sanitation Product and Services in accordance with the terms, conditions, and requirements set forth in the Request for Proposals (“RFP”) Statements for consideration by the Region One ESC and its members. Region One ESC Purchasing Department will receive request for proposals for School Nutrition Program Food Safety and Sanitation Product and Services 19-AGENCY-000055 electronically through the eBuyOne website: https://esc1.buyspeed.com/bso/ no later than 3 PM CST, Thursday, August 2, 2018. Late submittals will not be considered. Questions/clarifications regarding this RFP must be submitted in writing through the “Bid Q&A” tab located within the bid solicitation available through the eBuyOne website: https://esc1.buyspeed.com/bso/ no later than 3 PM, Friday, July 27, 2018. Questions/clarifications regarding this RFP will not be answered by phone. It is the Respondent’s responsibility to view the webpage regularly, or prior to submitting a response, to view any response(s) to question(s) issued for this solicitation. Responses to inquiries which directly affect an interpretation or change to this RFP will be issued in writing by Region One ESC as an addendum. All such addenda/additional information issued/posted to https://esc1.buyspeed.com/bso/ prior to the time that proposals are received shall be considered part of the RFP, and the Respondent shall be required to consider and acknowledge receipt of each addendum in its Response. -

The Films Are Numbered to Make It Easier to Find Projects in the List, It Is Not Indicative of Ranking

PLEASE NOTE: The films are numbered to make it easier to find projects in the list, it is not indicative of ranking. Division 1 includes schools in the 1A-4A conference. Division 2 includes schools in the 5A and 6A conference. Division 1 Digital Animation 1. Noitroba San Augustine High School, San Augustine 2. The Guiding Spirit New Tech HS, Manor 3. Penguins Hallettsville High School, Hallettsville 4. Blimp and Crunch Dublin High School, Dublin 5. Pulse Argyle High School, Argyle 6. Waiting for Love Argyle High School, Argyle 7. Catpucchino Salado High School, Salado 8. Angels & Demons Stephenville High School, Stephenville 9. Hare New Tech HS, Manor 10. Sketchy Celina High School, Celina 11. The Red Yarn Celina High School, Celina 12. Streetlight Sabine Pass High School, Sabine Pass Division 1 Documentary 1. New Mexico Magic, Andrews High School, Andrews 2. Mission to Haiti Glen Rose High School, Glen Rose 3. Angels of Mercy Argyle High School, Argyle 4. "I Can Do It" Blanco High School, Blanco 5. Sunset Jazz Celina High School, Celina 6. South Texas Maize Lytle High School, Lytle 7. Veterans And Their Stories Comal Canyon Lake High School, Fischer 8. Voiceless Salado High School, Salado 9. Lufkin Industires Hudson High School, Lufkin 10. The 100th Game Kenedy High School, Kenedy 11. The Gift of Healing Kenedy High School, Kenedy 12. Camp Kenedy Kenedy High School, Kenedy Division 1 Narrative 1. ; Livingston High School, Livingston 2. Dark Reflection Anna High School, Anna 3. Love At No Sight Pewitt High School, Omaha 4. The Pretender: Carthage High School, Carthage 5. -

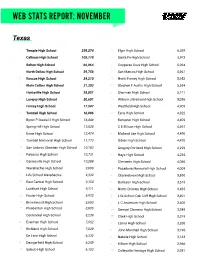

Web Stats Report: November

WEB STATS REPORT: NOVEMBER Texas 1 Temple High School 259,274 31 Elgin High School 6,029 2 Calhoun High School 108,778 32 Santa Fe High School 5,973 3 Belton High School 66,064 33 Copperas Cove High School 5,964 4 North Dallas High School 59,756 34 San Marcos High School 5,961 5 Roscoe High School 34,210 35 North Forney High School 5,952 6 Klein Collins High School 31,303 36 Stephen F Austin High School 5,554 7 Huntsville High School 28,851 37 Sherman High School 5,211 8 Lovejoy High School 20,601 38 William J Brennan High School 5,036 9 Forney High School 17,597 39 Westfield High School 4,909 10 Tomball High School 16,986 40 Early High School 4,822 11 Byron P Steele I I High School 16,448 41 Kempner High School 4,809 12 Spring Hill High School 13,028 42 C E Ellison High School 4,697 13 Ennis High School 12,474 43 Midland Lee High School 4,490 14 Tomball Memorial High School 11,773 44 Odem High School 4,470 15 San Antonio Christian High School 10,783 45 Gregory-Portland High School 4,299 16 Palacios High School 10,731 46 Hays High School 4,235 17 Gainesville High School 10,288 47 Clements High School 4,066 18 Waxahachie High School 9,609 48 Pasadena Memorial High School 4,009 19 Life School Waxahachie 9,332 49 Channelview High School 3,890 20 East Central High School 9,150 50 Burleson High School 3,615 21 Lockhart High School 9,111 51 North Crowley High School 3,485 22 Foster High School 8,972 52 Life School Oak Cliff High School 3,401 23 Brownwood High School 8,803 53 L C Anderson High School 3,400 24 Pleasanton High School 8,605 54 Samuel -

October 23, 2019 Good Morning Chairman Allen and Members Of

October 23, 2019 Good morning Chairman Allen and members of the Committee on the Judiciary and Public Safety. Thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Sasha Buchert and I’m a Senior Attorney at Lambda Legal. I’m testifying in support of the Tony Hunter and Bella Evangelista Panic Defense Prohibition Act of 2019 and in support of the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Panic Defense Prohibition Act of 2019. LGBTQ people, and transgender women of color in particular, move through the world under the constant threat of impending violence. In the words of one transgender woman of color in a recent New York Times article, “it’s always in the forefront of our minds, when we’re leaving home, going to work, going to school.”1 This fear is well-substantiated. At least 21 transgender people, almost all of them transgender women of color have been murdered this year already.2 Almost all of the murders involve the victims being shot multiple times, and commonly involve beatings and burnings. Two of those murders this year took place in the DC area; Zoe Spears a Black transgender woman, was found lying in the street with signs of trauma near Eastern Avenue in Fairmount Heights last June and Ashanti Carmon, also a black transgender woman was fatally shot this year in Prince George's County, Maryland.3 There has also been a troubling increase in violence targeting people based on their sexual orientation. Hate crimes have increased nationally over the last three years,4 and there were a record number of suspected hate crimes in D.C. -

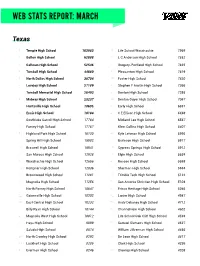

Web Stats Report: March

WEB STATS REPORT: MARCH Texas 1 Temple High School 163983 31 Life School Waxahachie 7969 2 Belton High School 62888 32 L C Anderson High School 7852 3 Calhoun High School 52546 33 Gregory-Portland High School 7835 4 Tomball High School 44880 34 Pleasanton High School 7619 5 North Dallas High School 38704 35 Foster High School 7420 6 Lovejoy High School 27189 36 Stephen F Austin High School 7366 7 Tomball Memorial High School 26493 37 Denton High School 7295 8 Midway High School 23237 38 Denton Guyer High School 7067 9 Huntsville High School 18605 39 Early High School 6881 10 Ennis High School 18184 40 C E Ellison High School 6698 11 Southlake Carroll High School 17784 41 Midland Lee High School 6567 12 Forney High School 17767 42 Klein Collins High School 6407 13 Highland Park High School 16130 43 Kyle Lehman High School 5995 14 Spring Hill High School 15982 44 Burleson High School 5917 15 Braswell High School 15941 45 Cypress Springs High School 5912 16 San Marcos High School 12928 46 Elgin High School 5634 17 Waxahachie High School 12656 47 Roscoe High School 5598 18 Kempner High School 12036 48 Sherman High School 5564 19 Brownwood High School 11281 49 Trimble Tech High School 5122 20 Magnolia High School 11256 50 San Antonio Christian High School 5104 21 North Forney High School 10647 51 Frisco Heritage High School 5046 22 Gainesville High School 10302 52 Lanier High School 4987 23 East Central High School 10232 53 Andy Dekaney High School 4712 24 Billy Ryan High School 10144 54 Channelview High School 4602 25 Magnolia West High School -

SB-2 Submitted On: 2/7/2019 9:40:07 AM Testimony for JDC on 2/12/2019 9:00:00 AM

SB-2 Submitted on: 2/7/2019 9:40:07 AM Testimony for JDC on 2/12/2019 9:00:00 AM Testifier Present at Submitted By Organization Position Hearing Testifying for Public John Tonaki Oppose Yes Defender Comments: Office of the Public Defender State of Hawai‘i Testimony of the Office of the Public Defender, State of Hawai‘i to the Senate Committee on Judiciary February 12, 2019 S.B. No. 2: RELATING TO CRIMINAL DEFENSE Chair Rhoads, Vice Chair Wakai and Members of the Committee: The Office of the Public Defender opposes S.B. No. 2. This measure would prohibit the accused from claiming discovery, knowledge, or disclosure of a victim’s gender, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual orientation resulted in extreme mental or emotional disturbance sufficient to reduce a charge of murder to a charge of manslaughter unless the other circumstances of a defendant’s explanation are already sufficient to reasonably find extreme mental or emotional disturbance. Our current manslaughter statute provides, in pertinent part, “The reasonableness of the explanation shall be determined from the viewpoint of a reasonable person in the circumstances as the defendant believed them to be. The added language is simply not necessary for fair application of the defense. A defendant asserting the affirmative defense of EMED must present a reasonable explanation for the defendant to be under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance. The trier-of-fact has always should determine the reasonableness of the accused’s explanation from the viewpoint of a reasonable person in the circumstances as the accused believed them to be Moreover, this measure would create a “preferred class” of individuals to the exclusion others who might equally be aggrieved as potential victims of manslaughter. -

Off-Campus Instruction Plan SUBMITTED to TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION REGIONAL COUNCIL

2021-2022 SOUTH TEXAS COLLEGE Off-Campus Instruction Plan SUBMITTED TO TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION REGIONAL COUNCIL PO Box 9701 McAllen, Texas 78502-9701 Office of the Vice President for Academic Affairs (956) 872-8339 3201 W. Pecan Blvd. McAllen, Texas 78501 Fax (956) 872-8388 Memorandum DATE: May 28, 2021 TO: Texas Higher Education Regional Council FROM: Dr. Anahid Petrosian, Interim Vice President for Academic Affairs CC: Dr. Andrew Lofters, Manager II, Academic Quality and Workforce Dr. David Plummer, Interim President, South Texas College RE: 2021-2022 Off-Campus Instruction Plan for South Texas College _______________________________________________________________________________ South Texas College submits for review and approval its 2021-2022 Off-Campus Instruction Plan (Plan) to the members of the Texas Higher Education Regional Council and the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. The following information is included in this Plan: • Programs Requiring HERC Approval • Programs Requiring HERC Notification • Courses Requiring HERC Notification In addition, South Texas College is scheduled to offer the following new programs on-campus for the 2021-2022 academic year: • Associate of Applied Science in Culinary Arts: Specialization – Restaurant Management • EMT-Basic Non-Credit Certificate • Production, Logistics & Maintenance Technician Non-Credit Certificate South Texas College looks forward to partnerships and collaborations as we serve the students of South Texas. Thank you. TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION REGIONAL COUNCIL OFF-CAMPUS INSTRUCTIONAL PLAN FOR 2021-2022 Institution Name: South Texas College Regional Council: Region 8 - South Texas Contact Person: Dr. Anahid Petrosian Email Address: [email protected] Phone: (956) 872-8339 Delivery location: Delivery Program Site name and community. Status: Type: Geographically Agreement in Award(s): (AAS, Cert1, Type: Highlighted locations added Program Area: CIP#/Title [C], [F2F], Responsible place/ etc.) [DC], [LD], since last report. -

The Trans Panic Defense: Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and the Murder of Transgender Women, 66 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 66 | Issue 1 Article 2 12-2014 The rT ans Panic Defense: Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and the Murder of Transgender Women Cynthia Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Recommended Citation Cynthia Lee, The Trans Panic Defense: Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and the Murder of Transgender Women, 66 Hastings L.J. 77 (2014). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol66/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Lee&Kwan_21 (TEIXEIRA).DOCX (Do Not Delete) 11/26/2014 2:20 PM The Trans Panic Defense: Masculinity, Heteronormativity, and the Murder of Transgender Women Cynthia Lee* and Peter Kwan** When a heterosexual man is charged with murdering a transgender woman with whom he has been sexually intimate, one defense strategy is to assert what has been called the trans panic defense. The defendant claiming this defense will say that the discovery that the victim was biologically male provoked him into a heat of passion causing him to lose self-control. If the jury finds that the defendant was actually and reasonably provoked, it can acquit him of murder and find him guilty of the lesser offense of voluntary manslaughter. The trans panic defense strategy is troubling because it appeals to stereotypes about transgender individuals as sexually deviant and abnormal. In this article, we examine the cultural structures of masculinity that may lead a man to kill a transgender woman with whom he has been sexually intimate. -

GOP Over Anti-LGBT Platform CLEVELAND – the First Openly Gay Member of the Republican Party’S Platform Committee Said July 19 She Does Not “Plan to Leave” the GOP

Election 2016: Democrats Ratify Most Pro-LGBT Platform Ever 3 pg. 7 Aug. 2 Primary Could Put Three More Out Candiates on Nov. Ballot Dem VEEP Pick has Strong LGBT Advocacy Record BTL Talks with 'Looking' Creator Michael Lannan KHAOS REIGNS AT HOTTER THAN JULY INTERNET SENSATION TO HOST LIVE SHOW AT PALMER PARK PICNIC pg. 20 WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM JULY 28, 2016 | VOL. 2430 | FREE ELECTION 2016 Follow our DNC coverage online CREEP OF THE WEEK COVER 20 Khaos Reigns at HTJ, Internet Sensation to Host Live Show at Palmer Park Picnic. Photo: Jason Michale NEWS In spite of promises from 4 Study Finds LGBT Adults Experience Food Trump to “protect” LGBTQ Insecurity people, his party’s platform 6 Aug. 2 Michigan Primary Could Put Three is most anti-gay in history! Additional Out Gay Candidates On Nov. 8 Ballot Platform comparison is stark! RNC looks to reverse marriage 7 Democrats Ratify Most Pro-LGBT Platform Ever equality, DNC looks to achieve full equality 8 GOP Convention Wrap-Up See page 17 See page 12 9 Dem VEEP Tim Kaine Has Strong LGBT Record 14 Jeffrey Montgomery, LGBTQ Leader Dies at 63 20 Khaos Reigns at HTJ, Internet Sensation to Host FERNDALE COVER STORY: HTJ Live Show at Palmer Park Picnic July 30 21 HTJ Spotlight: Kai Edwards 23 Great Lakes Folk Festival Celebrates Culture, Tradition and Communit, A Conversation with Rhonda Ross Legendary Singer’s Daughter is a Star in Her Own Right OPINION 12 Parting Glances 11 Viewpoint: Dana Rudolph 11 Creep of the Week: Donald Trump LIFE Transgender Pride in the Park 25 Through the ‘Looking’ Glass Coming Up, Commemorates 28 Transgender Pride in the Park Commemorates See page 22 Compton’s Cafeteria Riots 1966 Compton Riots 30 Happenings 32 Classifieds See page 28 See Coverage page 20 – 22 33 Frivolist: 6 Tricks to Throwing the Gayest Pool Party Ever VOL. -

Gay Panic Defense By: Kevin Drahos

Human Rights Committee - Introduced Anu Lamsal Jillian Baker Kevin Drahos Sydney Uhlman Tyler Juffernbruch Will Keck Gay Panic Defense By: Kevin Drahos Contact: Kevin Drahos | Cedar Rapids, IA | [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________________ Position Statement: The State of Iowa Youth Advisory Council supports legislation requiring the elimination of the gay and trans panic defense. Position It is the position of the State of Iowa Youth Advisory Council, the voice of Iowa’s youth, that legislation pertaining to elimination of the gay and trans panic defense be enacted. Rationale The gay panic defense is an attempted legal defense, usually against charges of assault or murder. A defendant using the defense claims they acted in a state of violent temporary insanity because of unwanted same-sex sexual advances [4]. The defendant alleges to find the same-sex sexual advances so offensive and frightening that it brings on a psychotic state characterized by unusual violence. The Trans panic is a similar defense applied in cases of assault, manslaughter, or murder of a transgender individual, with whom the assailant(s) engaged in sexual relations unaware that the victim is transgender until seeing them naked, or further into or post sexual activity [6]. This defense tactic is utilized when unwanted advancements are made towards heterosexuals by members of the LGBTQ+ community; however, any justification for murdering or brutalizing a member of the LGBTQ+ community solely because of their sexuality or gender caused panic perpetuates homophobia and transphobia [5]. The most infamous example of the gay trans panic defense is the story of Matthew Shepard: beaten, tortured, and brutally murdered by two men.