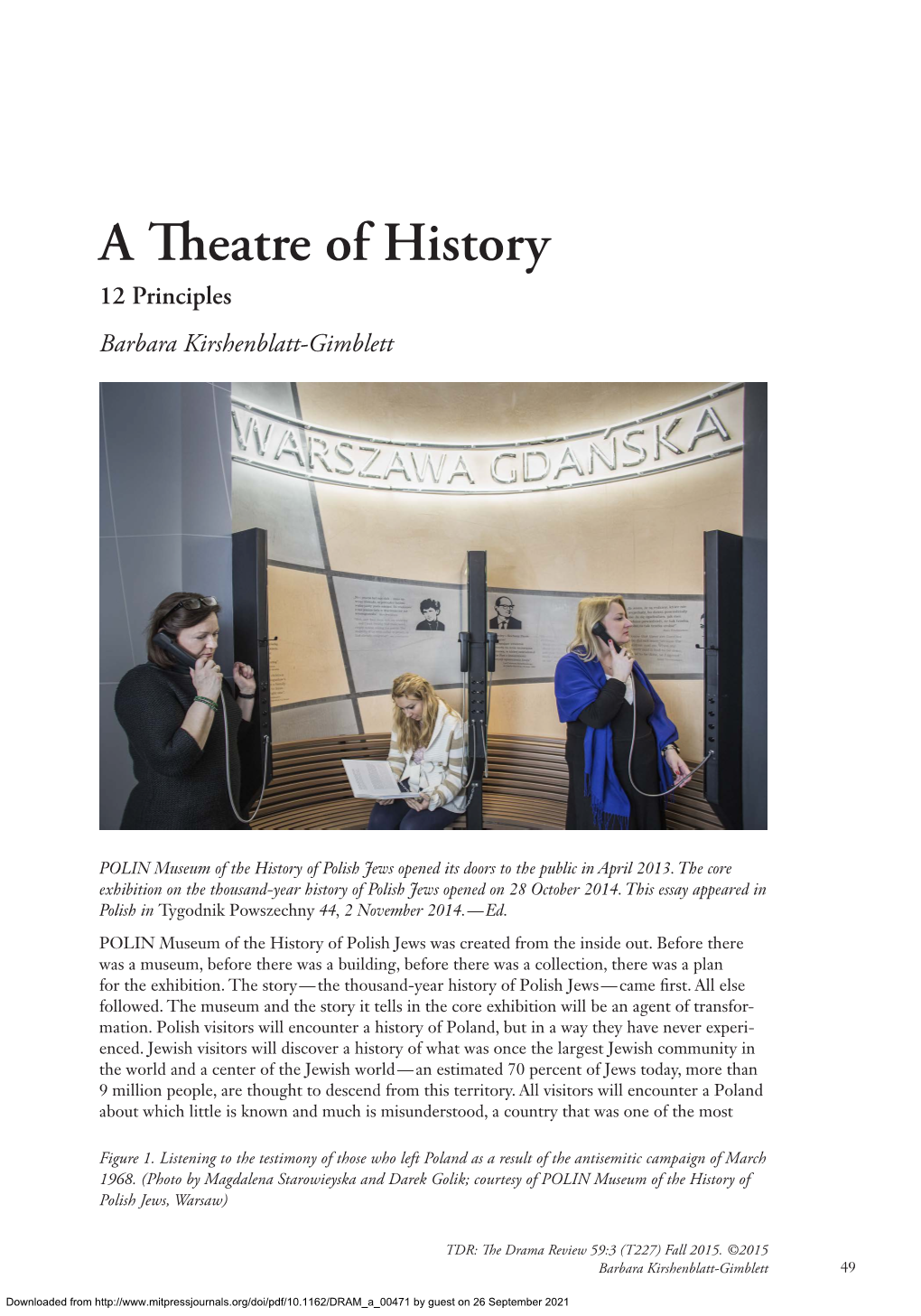

A Theatre of History 12 Principles Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—An Outline

The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland ♦ 1 The Influence of Progressive Judaism in Poland—an Outline Michał Galas Jagiellonian University In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands the influence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his paper fills the gap in historiography by giving some examples of activities of progressive communities and their leaders. It focuses mainly on eminent rabbis and preachers such as Abraham Goldschmidt, Markus Jastrow, and Izaak Cylkow. Supporters of progressive Judaism in Poland did not have as strong a position as representatives of the Reform or Conservative Judaism in Germany or the United States. Religious reforms introduced by them were for a number of reasons moderate or limited. However, one cannot ignore this move- ment in the history of Judaism in Poland, since that trend was significant for the history of Jews in Poland and Polish-Jewish relations. In the historiography of Judaism in the Polish lands, the history of the influ- ence of Reform Judaism is often overlooked. he opinion is frequently cited that the Polish Jews were tied to tradition and did not accept ideas of religious reform coming from the West. his opinion is perhaps correct in terms of the number of “progressive” Jews, often so-called proponents of reform, on Polish soil, in comparison to the total number of Polish Jews. However, the influence of “progressives” went much further and deeper, in both the Jewish and Polish community. -

Readings on the Encounter Between Jewish Thought and Early Modern Science

HISTORY 449 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA W 3:30pm-6:30 pm Fall, 2016 GOD AND NATURE: READINGS ON THE ENCOUNTER BETWEEN JEWISH THOUGHT AND EARLY MODERN SCIENCE INSTRUCTOR: David B. Ruderman OFFICE HRS: M 3:30-4:30 pm;W 1:00-2:00 OFFICE: 306b College Hall Email: [email protected] SOME GENERAL WORKS ON THE SUBJECT: Y. Tzvi Langerman, "Jewish Science", Dictionary of the Middle Ages, 11:89-94 Y. Tzvi Langerman, The Jews and the Sciences in the Middle Ages, 1999 A. Neher, "Copernicus in the Hebraic Literature from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century," Journal History of Ideas 38 (1977): 211-26 A. Neher, Jewish Thought and the Scientific Revolution of the Sixteenth Century: David Gans (1541-1613) and His Times, l986 H. Levine, "Paradise not Surrendered: Jewish Reactions to Copernicus and the Growth of Modern Science" in R.S. Cohen and M.W. Wartofsky, eds. Epistemology, Methodology, and the Social Sciences (Boston, l983), pp. 203-25 H. Levine, "Science," in Contemporary Jewish Religious Thought, eds. A. Cohen and P. Mendes-Flohr, l987, pp. 855-61 M. Panitz, "New Heavens and a New Earth: Seventeenth- to Nineteenth-Century Jewish Responses to the New Astronomy," Conservative Judaism, 40 (l987-88); 28-42 D. Ruderman, Kabbalah, Magic, and Science: The Cultural Universe of a Sixteenth- Century Jewish Physician, l988 D. Ruderman, Science, Medicine, and Jewish Culture in Early Modern Europe, Spiegel Lectures in European Jewish History, 7, l987 D. Ruderman, Jewish Thought and Scientific Discovery in Early Modern Europe, 1995, 2001 D. Ruderman, Jewish Enlightenment in an English Key: Anglo-Jewry’s Construction of Modern Jewish Thought, 2000 D. -

Kultura Muzyczna W Polsce D

Katarzyna Janczewska-Sołomko KULTURA MUZYCZNA W POLSCE DWUDZIESTOLECIA MIĘDZYWOJENNEGO (NA PRZYKŁADZIE NAGRAŃ) Skrót Rok 1919 jest – jak wiadomo – ważny dla historii Europy, w tym także dla historii Polski. Był to początek funkcjonowania krajów w nowych granicach geograficznych, w nowych warunkach politycznych, ze świadomością początków nowej ery i możliwości istnienia w okolicznościach pokojowych. Dwudziestolecie międzywojenne było w Polsce okresem wielkich przemian; oznaczało między innymi odbudowę instytucji niezależnych od obcej ingerencji, a także zmianę potrzeb w sferze kultury. Prężnie działały czołowe instytucje kultury (Filharmonia Warszawska, Opera Warszawska), duże ożywienie związane było z organizacją pierwszych konkursów międzynarodowych: w 1927 r. im. F. Chopina i w 1935 – im. H. Wieniawskiego. W Polsce koncertowali czołowi polscy artyści (m.in. Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Artur Rubinstein, Ignacy Friedman, Bronisław Huberman, Henryk Szeryng, Ewa Bandrowska-Turska, zaczyna swoją wspaniałą karierę Witold Małcużyński) i wielu wybitnych wykonawców z zagranicy. Powstają liczne chóry i zespoły instrumentalne. W repertuarze koncertowym coraz częściej pojawiają się utwory m.in. Karola Szymanowskiego i innych polskich twórców tego okresu. Lata 1919-1939 w Polsce to także okres rozkwitu teatrzyków i kabaretów, spośród najbardziej znane to Morskie Oko oraz Qui pro quo. Na potrzeby polskich odbiorców do piosenek obcej proweniencji autorzy często tworzyli nowe teksty i utwór zaczynał żyć własnym życiem; w niepamięć szedł autor oryginału… Mistrzami polskich wersji tekstów zagranicznych byli Marian Hemar, Andrzej Włast, Emanuel Schlechter, a także Julian Tuwim i inni. Teatrzyki i kabarety lansowały przeboje, ale było to głównie zasługą wykonawców; legendarna Hanka Ordonówna, Tola Mankiewiczówna, Zofia Terné, Mira Zimińska, Eugeniusza Bodo , Mieczysław Fogg – to tylko niektórzy z nich. Ponadto istniały chóry rewelersów, spośród których najbardziej popularny był Chór Dana, kierowany przez Władysława Daniłowskiego, psed. -

Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Women's Studies Faculty Publications Women’s Studies 2010 Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Milligan, Amy, "Shulchan Arukh" (2010). Women's Studies Faculty Publications. 10. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs/10 Original Publication Citation Milligan, A. (2010). Shulchan Arukh. In D. M. Fahey (Ed.), Milestone documents in world religions: Exploring traditions of faith through primary sources (Vol. 2, pp. 958-971). Dallas: Schlager Group:. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains in the fifteenth century (Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains, illustration by Michelet c.1900 (colour litho), Bombled, Louis (1862-1927) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / The Bridgeman Art Library International) 958 Milestone Documents of World Religions Shulchan Arukh 1570 ca. “A person should dress differently than he does on weekdays so he will remember that it is the Sabbath.” Overview Arukh continues to serve as a guide in the fast-paced con- temporary world. The Shulchan Arukh, literally translated as “The Set Table,” is a compilation of Jew- Context ish legal codes. -

The Legal Status of Abuse

HM 424.1995 FAMILY VIOLENCE Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff Part 1: The Legal Status of Abuse This paper was approved by the CJT,S on September 13, 1995, by a vote of' sixteen in favor and one oppossed (16-1-0). V,,ting infiwor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Ben :Lion BerBm<m, Stephanie Dickstein, £/liot JY. Dorff, S/wshana Gelfand, Myron S. Geller, Arnold i'H. Goodman, Susan Crossman, Judah f(ogen, ~bnon H. Kurtz, Aaron L. iHaclder, Hwl 11/othin, 1'H(~yer HabinoLviiz, Joel /t.,'. Rembaum, Gerald Slwlnih, and E/ie Kaplan Spitz. hJting against: H.abbi Ceraicl Ze/izer. 1he Committee 011 .lnuish L(Lw and Standards qf the Rabhinical As:wmbly provides f};ztidance in matters (!f halakhnh for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, hou;evet~ is the authority for the interpretation and application of all maltrrs of halaklwh. 1. Reating: According to Jewish law as interpreted by the Conservative movement, under what circumstance, if any, may: A) husbands beat their wives, or wives their husbands? B) parents beat their children? c) adult children of either gender beat their elderly parents? 2. Sexual abu.se: What constitutes prohibited sexual abuse of a family member? 3· verbal abuse: What constitutes prohibited verbal abuse of a family member? TI1e Importance of the Conservative Legal Method to These Issues 1 In some ways, it would seem absolutely obvious that Judaism would nut allow individu als to beat others, especially a family member. After all, right up front, in its opening l T \VOuld like to express my sincere thanks to the members or the Committee on Jew·isll Law and Standards for their hdpfu I snggc:-;tions for impruving an earlier draft of this rcsponsum. -

Institute of National Remembrance

Institute of National Remembrance https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/8027,The-IPN-paid-tribute-to-the-insurgents-from-the-Warsaw-Ghetto.html 2021-09-30, 23:04 19.04.2021 The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto The IPN paid tribute to the insurgents from the Warsaw Ghetto on the occasion of the 78th anniversary of the Uprising. The Deputy President of the Institute, Mateusz Szpytma Ph.D., and the Director of the IPN Archive, Marzena Kruk laid flowers in front of the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in Warsaw on 19 April 2021. On 19 April 1943, fighters from the Jewish Fighting Organization (ŻOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW) mounted armed resistance against German troops who liquidated the ghetto. It was the last act of the tragedy of Warsaw Jews, mass-deported to Treblinka German death camp. The Uprising lasted less than a month, and its tragic epilogue was the blowing up of the Great Synagogue in Tłomackie Street by the Germans. It was then that SS general Jürgen Stroop, commanding the suppression of the Uprising, who authored the report documenting the course of fighting in the Ghetto (now in the resources of the Institute of National Remembrance) could proclaim that "the Jewish district in Warsaw no longer exists." On the 78th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Institute of National Remembrance would like to encourage everyone to learn more about the history of the uprising through numerous publications, articles and educational materials which are available on the Institute's website and the IPN’s History Point website: https://ipn.gov.pl/en https://przystanekhistoria.pl/pa2/tematy/english-content The IPN has been researching the history of the Holocaust and Polish- Jewish relations for many years. -

The Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street

The Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street “There is no trace of Warsaw’s largest synagogue in The Bank Square. It was a symbol of Reform Judaism in the capital and one of the greatest Polish buildings built in the 19th century”. So says of the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street Hanna Dzielińska (Hanka Warszawianka), journalist and tourist guide. The eighth episode of ‘Remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto’ also tells the story of the adjacent building of the Main Judaic Library, the Oneg Shabbat group operating next to it, and the largest project of its participants – the Ringelblum archive. ‘Remnants of the Warsaw Ghetto’ is a film series of 16 short guided tours presenting the history of places and people associated with them. The following places will be presented: Umschlagplatz; Anielewicz Mound; Szmul Zygielbojm Monument; Monument of the Ghetto Heroes; Grzybowski Square; Mariańska Street and the Nursing School; Nożyk Synagogue; Great Synagogue at Tłomackie Street; Nalewki Street; Femina Cinema Theater; Courts at Leszno Street; Chłodna Street; Waliców Street; The Jewish Cemetery at Okopowa Street, and the Bersohn and Bauman Hospital – the place where the permanent exhibition of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum will be created. The series presentation accompanies the commemoration of 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto borders closing, organized by the Warsaw Ghetto Museum in cooperation with the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage and TSKŻ – the Social and Cultural Society of Jews in Poland. The main events took place on November 16, 2020. Publication date: 2021-08-19 Print date: 2021-09-18 11:46 Source: http://1943.pl/en/artykul/the-great-synagogue-on-tlomackie-street/. -

Maharam of Padua V. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright

Draft: July 2007 44 Houston Law Review (forthcoming 2007) Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright Neil Weinstock Netanel* Copyright scholars are almost universally unaware of Jewish copyright law, a rich body of copyright doctrine and jurisprudence that developed in parallel with Anglo- American and Continental European copyright laws and the printers’ privileges that preceded them. Jewish copyright law traces its origins to a dispute adjudicated some 150 years before modern copyright law is typically said to have emerged with the Statute of Anne of 1709. This essay, the beginning of a book project about Jewish copyright law, examines that dispute, the case of the Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani. In 1550, Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen of Padua (known by the Hebrew acronym, the “Maharam” of Padua) published a new edition of Moses Maimonides’ seminal code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah. Katzenellenbogen invested significant time, effort, and money in producing the edition. He and his son also added their own commentary on Maimonides’ text. Since Jews were forbidden to print books in sixteenth- century Italy, Katzenellenbogen arranged to have his edition printed by a Christian printer, Alvise Bragadini. Bragadini’s chief rival, Marc Antonio Giustiniani, responded by issuing a cheaper edition that both copied the Maharam’s annotations and included an introduction criticizing them. Katzenellenbogen then asked Rabbi Moses Isserles, European Jewry’s leading juridical authority of the day, to forbid distribution of the Giustiniani edition. Isserles had to grapple with first principles. At this early stage of print, an author- editor’s claim to have an exclusive right to publish a given book was a case of first impression. -

Jewish Law Research Guide

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Library Research Guides - Archived Library 2015 Jewish Law Research Guide Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides Part of the Religion Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Library, "Jewish Law Research Guide" (2015). Law Library Research Guides - Archived. 43. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/researchguides/43 This Web Page is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Library Research Guides - Archived by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Home - Jewish Law Resource Guide - LibGuides at C|M|LAW Library http://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/sites/1185/guides/190548/backups/gui... C|M|LAW Library / LibGuides / Jewish Law Resource Guide / Home Enter Search Words Search Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life. Home Primary Sources Secondary Sources Journals & Articles Citations Research Strategies Glossary E-Reserves Home What is Jewish Law? Need Help? Jewish Law is called Halakha in Hebrew. Halakha from the Hebrew word Halakh, Contact a Law Librarian: which means "to walk" or "to go;" thus a literal translation does not yield "law," but rather [email protected] "the way to go". Phone (Voice):216-687-6877 Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and Text messages only: ostensibly non-religious life 216-539-3331 Jewish religious tradition does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

Brief History of the Holocaust, a Reference Tool, Montreal

Brief History of the Holocaust - A Reference Tool Brief History of the HOLOCAUST A Reference Tool 1 Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre 5151, chemin de la Côte-Sainte-Catherine (Maison Cummings) Montréal (Québec) H3W 1M6 Canada Téléphone : 514-345-2605 Télécopie : 514-344-2651 Courriel : [email protected] Site Web : www.mhmc.ca Produced by the Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre, 2012 Graphic design: Fabian Will - [email protected] Picture credits: MHMC,except for p. 27, Pierre St-Jacques and cover page, p. 31 et 33, Randall Bytwerk. The material in this Guide may be copied and distributed for educational purposes only. 2 Brief History of the Holocaust - A Reference Tool Table of Contents Montreal Holocaust Memorial Centre ..............................................................4 Introduction .....................................................................................................5 Historical Context ...........................................................................................6 Pre-Holocaust Jewish Communities ..........................................................6 Rise of Nazism ..........................................................................................7 Adolf Hitler Comes to Power .....................................................................8 Racist and Antisemitic Ideology .................................................................9 World War II .............................................................................................10 Ghettos ................................................................................................... -

Armed Resistance in the Ghettos and Camps

ARMED RESISTANCE IN THE GHETTOS AND CAMPS RESISTANCE IN THE GHETTOS On January 18, 1943, German forces entered the Warsaw the Germans withdrew from the ghetto. The remaining ghetto in order to arrest Jews and deport them. To inhabitants believed that the armed resistance combined their astonishment, young Jews offered them armed with the difficulties in finding Jews in hiding, had resistance and actually drove the German forces out of led to the end of the Aktion. As a result, over the next the ghetto before they were able to finish their ruthless months the armed undergrounds sought to strengthen task. This armed resistance came on the heels of the themselves and the vast majority of ghetto residents and great deportation that had occurred in the summer zealously built more and better bunkers in which to hide. and early autumn of 1942, which had resulted in the dispatch of 300,000 Jews, the vast majority of the ghetto’s inhabitants to Nazi camps, almost all to the Treblinka extermination camp. About 60,000 Jews remained in the ghetto, traumatized by the deportations and believing that the Germans had not deported them and would not deport them since they wanted their labor. Two undergrounds led by youth activists, with several hundred members, coalesced between the end of the first wave of deportations and the events of January. During four days in January, the Germans sought to round up Jews and the armed resistance continued. The ghetto inhabitants went through a swift change, Left: Waffen SS soldiers locating Jews in dugouts. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, 6003996 no longer believing that their value as labor would Right: HeHalutz women captured with weapons during the safeguard them.