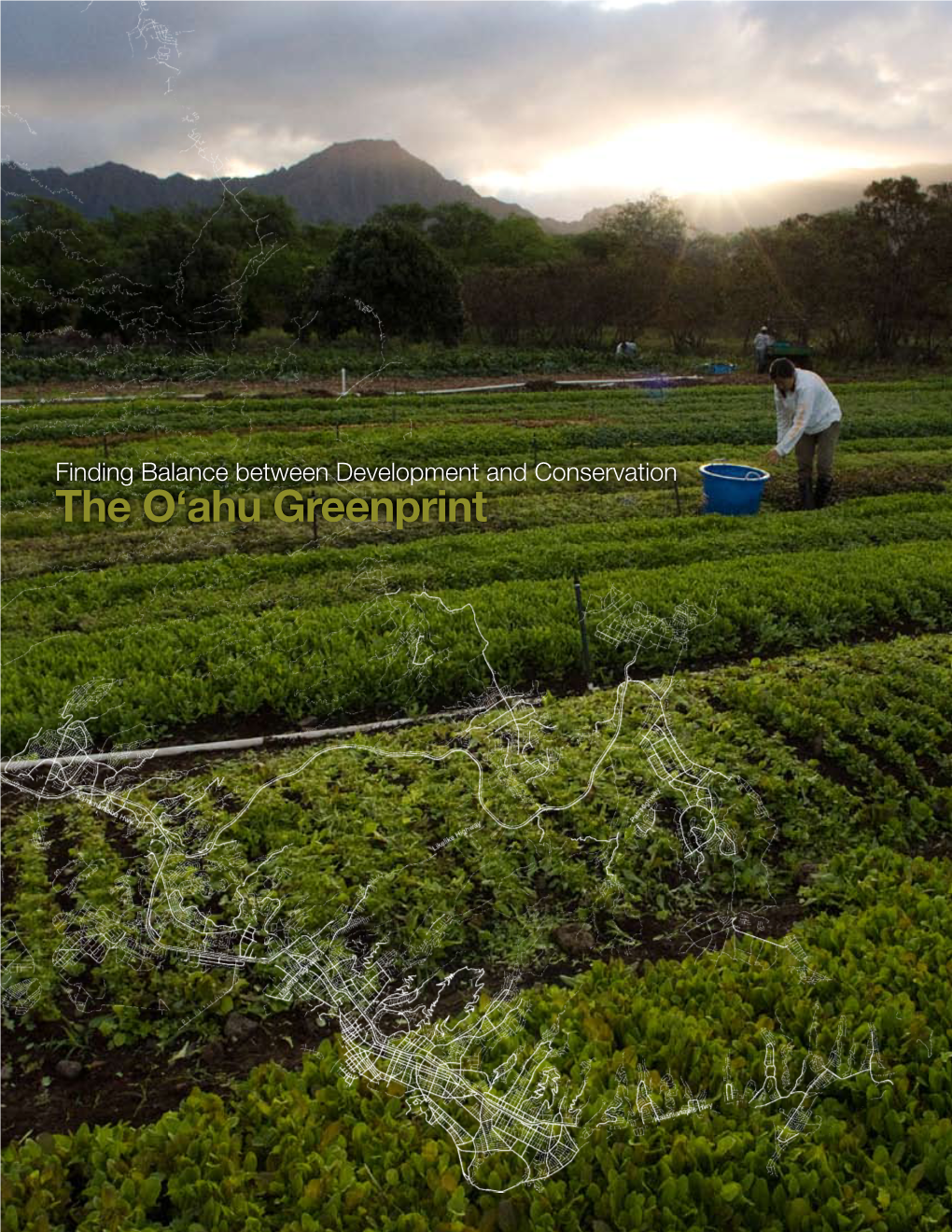

The O'ahu Greenprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHORT-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna Tenuirostris Non-Breeding Visitor, Occasional Migrant Monotypic

SHORT-TAILED SHEARWATER Ardenna tenuirostris non-breeding visitor, occasional migrant monotypic The Short-tailed Shearwater breeds on islands off S and SE Australia in Nov- May, disperses northward through the W Pacific to the Bering Sea in May-Aug, and migrates rapidly southwestward in large flights across the central Pacific, back the breeding grounds, in Sep-Nov (King 1967, Harrison 1983, AOU 1998, Howell 2012). In the Hawaiian Islands, large numbers have been recorded during well-defined pulses in fall migration, and several sight observations of one to a few birds suggest a smaller passage in spring. The Short-tailed Shearwater is extremely difficult to separate from the similar Sooty Shearwater in the field (see Sooty Shearwater), especially when viewing isolated individuals (King 1970); thus, confirmation of the spring passage with specimen or photographic evidence is desirable. Short-tailed Shearwater was placed in genus Puffinus until moved to Ardenna by the AOU (2016). At sea, Short-tailed Shearwaters were recorded in large numbers during 2002 HICEAS, with 37,874 individuals observed on 52 of 163 observing days from W of Kure to S of Oahu (Rowlett 2002; HICEAS data); they were observed from 1 Sep to 14 Nov. Over 1,000 birds were recorded on each of seven dates, with a large peak of >28,000 recorded 13-22 Sep 2002 between Midway and Lisianski and a smaller peak of >4,000 recorded 30 Oct-14 Nov between Laysan and Kaua'i. All birds were flying SSW in concentrated groups. In contrast to Sooty Shearwater, Short-taileds were clearly more abundant in Northwestern than Southeastern Hawaiian Island waters during fall passage; only 66 birds were recorded on 3 of 35 dates during this period off the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands. -

Geology of Hawaii Reefs

11 Geology of Hawaii Reefs Charles H. Fletcher, Chris Bochicchio, Chris L. Conger, Mary S. Engels, Eden J. Feirstein, Neil Frazer, Craig R. Glenn, Richard W. Grigg, Eric E. Grossman, Jodi N. Harney, Ebitari Isoun, Colin V. Murray-Wallace, John J. Rooney, Ken H. Rubin, Clark E. Sherman, and Sean Vitousek 11.1 Geologic Framework The eight main islands in the state: Hawaii, Maui, Kahoolawe , Lanai , Molokai , Oahu , Kauai , of the Hawaii Islands and Niihau , make up 99% of the land area of the Hawaii Archipelago. The remainder comprises 11.1.1 Introduction 124 small volcanic and carbonate islets offshore The Hawaii hot spot lies in the mantle under, or of the main islands, and to the northwest. Each just to the south of, the Big Island of Hawaii. Two main island is the top of one or more massive active subaerial volcanoes and one active submarine shield volcanoes (named after their long low pro- volcano reveal its productivity. Centrally located on file like a warriors shield) extending thousands of the Pacific Plate, the hot spot is the source of the meters to the seafloor below. Mauna Kea , on the Hawaii Island Archipelago and its northern arm, the island of Hawaii, stands 4,200 m above sea level Emperor Seamount Chain (Fig. 11.1). and 9,450 m from seafloor to summit, taller than This system of high volcanic islands and asso- any other mountain on Earth from base to peak. ciated reefs, banks, atolls, sandy shoals, and Mauna Loa , the “long” mountain, is the most seamounts spans over 30° of latitude across the massive single topographic feature on the planet. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

General Index

General Index Italicized page numbers indicate figures and tables. Color plates are in- cussed; full listings of authors’ works as cited in this volume may be dicated as “pl.” Color plates 1– 40 are in part 1 and plates 41–80 are found in the bibliographical index. in part 2. Authors are listed only when their ideas or works are dis- Aa, Pieter van der (1659–1733), 1338 of military cartography, 971 934 –39; Genoa, 864 –65; Low Coun- Aa River, pl.61, 1523 of nautical charts, 1069, 1424 tries, 1257 Aachen, 1241 printing’s impact on, 607–8 of Dutch hamlets, 1264 Abate, Agostino, 857–58, 864 –65 role of sources in, 66 –67 ecclesiastical subdivisions in, 1090, 1091 Abbeys. See also Cartularies; Monasteries of Russian maps, 1873 of forests, 50 maps: property, 50–51; water system, 43 standards of, 7 German maps in context of, 1224, 1225 plans: juridical uses of, pl.61, 1523–24, studies of, 505–8, 1258 n.53 map consciousness in, 636, 661–62 1525; Wildmore Fen (in psalter), 43– 44 of surveys, 505–8, 708, 1435–36 maps in: cadastral (See Cadastral maps); Abbreviations, 1897, 1899 of town models, 489 central Italy, 909–15; characteristics of, Abreu, Lisuarte de, 1019 Acequia Imperial de Aragón, 507 874 –75, 880 –82; coloring of, 1499, Abruzzi River, 547, 570 Acerra, 951 1588; East-Central Europe, 1806, 1808; Absolutism, 831, 833, 835–36 Ackerman, James S., 427 n.2 England, 50 –51, 1595, 1599, 1603, See also Sovereigns and monarchs Aconcio, Jacopo (d. 1566), 1611 1615, 1629, 1720; France, 1497–1500, Abstraction Acosta, José de (1539–1600), 1235 1501; humanism linked to, 909–10; in- in bird’s-eye views, 688 Acquaviva, Andrea Matteo (d. -

Photographing the Islands of Hawaii

Molokai Sea Cliffs - Molokai, Hawaii Photographing the Islands of Hawaii by E.J. Peiker Introduction to the Hawaiian Islands The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight primary islands and many atolls that extend for 1600 miles in the central Pacific Ocean. The larger and inhabited islands are what we commonly refer to as Hawaii, the 50 th State of the United States of America. The main islands, from east to west, are comprised of the Island of Hawaii (also known as the Big Island), Maui, Kahoolawe, Molokai, Lanai, Oahu, Kauai, and Niihau. Beyond Niihau to the west lie the atolls beginning with Kaula and extending to Kure Atoll in the west. Kure Atoll is the last place on Earth to change days and the last place on Earth to ring in the new year. The islands of Oahu, Maui, Kauai and Hawaii (Big Island) are the most visited and developed with infrastructure equivalent to much of the civilized world. Molokai and Lanai have very limited accommodation options and infrastructure and have far fewer people. All six of these islands offer an abundance of photographic possibilities. Kahoolawe and Niihau are essentially off-limits. Kahoolawe was a Navy bombing range until recent years and has lots of unexploded ordinance. It is possible to go there as part of a restoration mission but one cannot go there as a photo destination. Niihau is reserved for the very few people of 100% Hawaiian origin and cannot be visited for photography if at all. Neither have any infrastructure. Kahoolawe is photographable from a distance from the southern shores of Maui and Niihau can be seen from the southwestern part of Kauai. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

PDF (V.54:15 February 5, 1953)

C:Al,11 FlORMIIIA Cali/fJln/a Institute fJ/ Tec!1nfJlfJgy Volume LlV Pasadena, California, Thursday, February 5, 1953__.,...- No. 15 ·Honor keys distributed Heart Fund, WSSF, Red from merits of applications Tech men to submit itemized lists of deserved Honor Points in hopes of Keys and Certificates Feather Drive Rolls Monday If you have earned 100 honor. .' _ points since the beginning of I -d I e House that digs deepest wins prize th.ird term last year, you are eli- Frl ay ec·tures Ca Itech t Oj~Hd ISCUSS., The e I ed h' e f ' glble for an honor key. If you edt e I bl ' IS IS on y outsI e canty 0 year have earned 50 points, you are h- hi- ht ~ -, In us na. pro ems eligible for an honor certificate.' 19· 19 s air, The 1953 Consolidated Charities Drive starts on Monday, The deadline for all applications, The 1953 series of the Work- February 16. This year the charities represented are WSSF which will be considered by the Four Friday Evening Demon- shops on Communication, spon- (World Student Service Fund), Pasadena Community Chest, and Honor Point Committee, is Fri- stration Lectures, which should sored by the Caltech Industrial the American Heart Association. Each of the students will re day, February 20, 1953, at 7:00 be of more than passing interest Relations Section will be held ceive literature on these charities and information concerning am. All persons with 50 or to Tech students are planned for the second Tuesday of each these charities will appear in next week's Tech. -

Geothermal Power Development in Hawaii

GEOTHEBMAL POWER DEVELOPMENT IN HAWAII. '/' ¥olume I."" ..;:'~ DOE/ET/27l33--T2 Vol. 1 DE82 020077 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Under Contract DE-FC03-79ET27133 ,... DISCLAIMER ...., This report was prepared 85 an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof. nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, Of assumes any legal liability or responsibilitY for the accuracy. completeness. or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product. or process disclosed. or repretentJ that its use 'Mluld not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product. process, or !Jervice by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwtse, does not necessarily constitute or imply Its endorsement. recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. 'The views end opinions of authors expressed herein do not /- "----------------'-necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. .-/ Department of Planning and Economic Development State of Hawaii June 1982· -tV DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCmlfnn 'IS UNLIMITEO FOREWORD By Hideto Kono State Director of Planning and Economic Development and State Energy Resources Coordinator Hawaii imports about $1.5 billion in petroleum each year to provide the energy it needs. Meanwhile, there, are all around us prodigious alternate energy resources awaiting development. These include the sun itself; the wind; the heat of the earth, especially in our volcanic region on the Island of Hawaii; biomass--the things which grow from our fertile soil--and ocean thermal energy conversion. This new volume reviews and analyzes geothermal power development in Hawaii. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Laser Spectroscopy and Photodynamics of Alternative Nucleobases and Organic Dyes A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry by Jacob Alan Berenbeim Committee in charge: Professor Mattanjah de Vries, Chair Professor Steve Buratto Professor Michael Gordon Professor Martin Moskovits December 2017 The dissertation of Jacob Alan Berenbeim is approved. ____________________________________________ Steve Buratto ____________________________________________ Michael Gordon ____________________________________________ Martin Moskovits ____________________________________________ Mattanjah de Vries, Committee Chair October 2017 Laser Spectroscopy and Photodynamics of Alternative Nucleobases and Organic Dyes Copyright © 2017 by Jacob Alan Berenbeim iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To my wife Amy thank you for your endless support and for inspiring me to match your own relentless drive towards reaching our goals. To my parents and my brothers Eli and Gabe thank you for your love and visits to Santa Barbara, CA. To my advisor Mattanjah and my lab mates thank you for the incredible opportunity to share ideas and play puppets with the fabric of space. And to my cat Lola, you’re a good cat. iv VITA OF JACOB ALAN BERENBEIM October 2017 EDUCATION University of California, Santa Barbara CA Fall 2017 PhD, Physical Chemistry Advisor: Prof. Mattanjah S. de Vries University of Puget Sound, Tacoma WA 2009 BS, Chemistry Advisor: Prof. Daniel Burgard LABORATORY TECHNIQUES Photophysics by UV/VIS and IR pulsed laser spectroscopy, optical alignment, oa-TOF mass spectrometry (multiphoton ionization, MALDI, ESI+), molecular beam high vacuum apparatus, high voltage electronics, molecular computational modeling with Gaussian, data acquisition with LabView, and data manipulation with Mathematica and Origin RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Graduate Student Researcher 2012-2017 • Time dependent (transient) photo relaxation of organic molecules, including PAHs and aromatic biological molecules. -

O'ahu Bike Plan

o‘ahu bike plan a bicycle master plan August 2012 Department of Transportation Services City & County of Honolulu o‘ahu bike plan a bicycle master plan August 2012 Department of Transportation Services City & County of Honolulu Helber Hastert & Fee, Planners The Authors would like to acknowledge the leadership and contributions provided by the Director of the Department of T ransportation Services, Mr. Wayne Yoshioka, and the City’s Bicycle Coordinator, Mr. Chris Sayers. Other contributors included: Alta Planning + Design, San Rafael, California Engineering Concepts, Inc., Honolulu, Hawaii TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary . ES-1 1 Introduction . 1-1 1.1 Overview . 1-1 1.2 Plan Development . 1-3 1.3 Plan Organization ................................................1-7 2 Vision, Goals, Objectives . .2-1 2.1 Vision..........................................................2-1 2.2 Goals and Objectives .............................................2-2 3 The 5 E’s: Encouragement, Engineering, Education, Enforcement, Evaluation . .3-1 3.1 Encouragement .................................................3-2 3.2 Engineering.....................................................3-3 3.2.1 Maintenance....................................................3-3 3.2.2 Design Guidance . 3-4 3.3 Education . 3-6 3.4 Enforcement ....................................................3-7 3.5 Evaluation ......................................................3-8 3.6 Other Policy Initiatives . 3-9 3.6.1 Safe Routes to School . 3-9 3.6.2 Complete Streets . 3-9 4 Support Facilities . 4-1 4.1 Parking . 4-1 4.2 Showers/Changing Rooms . 4-3 4.3 Transit Integration . 4-4 5 Bikeway Network . 5-1 5.1 Existing Network.................................................5-3 5.2 Planned Facilities ................................................5-4 5.2.1 Project Prioritization and Methodology...............................5-4 5.2.2 Projected Costs and Funding......................................5-29 5.3 Short-Range Implementation Plan . -

User Guide to 1:250,000 Scale Lunar Maps

CORE https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19750010068Metadata, citation 2020-03-22T22:26:24+00:00Z and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by NASA Technical Reports Server USER GUIDE TO 1:250,000 SCALE LUNAR MAPS (NASA-CF-136753) USE? GJIDE TO l:i>,, :LC h75- lu1+3 SCALE LUNAR YAPS (Lumoalcs Feseclrch Ltu., Ottewa (Ontario) .) 24 p KC 53.25 CSCL ,33 'JIACA~S G3/31 11111 DANNY C, KINSLER Lunar Science Instltute 3303 NASA Road $1 Houston, TX 77058 Telephone: 7131488-5200 Cable Address: LUtiSI USER GUIDE TO 1: 250,000 SCALE LUNAR MAPS GENERAL In 1972 the NASA Lunar Programs Office initiated the Apollo Photographic Data Analysis Program. The principal point of this program was a detailed scientific analysis of the orbital and surface experiments data derived from Apollo missions 15, 16, and 17. One of the requirements of this program was the production of detailed photo base maps at a useable scale. NASA in conjunction with the Defense Mapping Agency (DMA) commenced a mapping program in early 1973 that would lead to the production of the necessary maps based on the need for certain areas. This paper is designed to present in outline form the neces- sary background informatiox or users to become familiar with the program. MAP FORMAT * The scale chosen for the project was 1:250,000 . The re- search being done required a scale that Principal Investigators (PI'S) using orbital photography could use, but would also serve PI'S doing surface photographic investigations. Each map sheet covers an area four degrees north/south by five degrees east/west.