Navigating Housing Development in the New Era Thursday, May 9, 2019 General Session; 9:00 – 10:30 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOME ECONOMICS Five New Models for Domestic Life Days Decades

HOME ECONOMICS Five new models for domestic life Months Years Hours Days Decades British Pavilion, Venice Architecture Biennale 2016 en it HOME ECONOMICS proposes new models for the frontline of British architecture: the home. HOME ECONOMICS is the science of household management. It intervenes directly in the architecture of the home, responding to changes in life and social norms through the design of the everyday. HOME ECONOMICS asks urgent questions about the role of housing and domestic space in the material reality of familiar life. HOME ECONOMICS is a truly collaborative proposal challenging financial models, categories of ownership, forms of life, social and gender power relations. HOME ECONOMICS understands that in housing there can be no metaphors. Each model in Home Economics is a proposition driven by the conditions imposed on domestic life by varying periods of occupancy. They each address different facets of how we live today – from whether we can prevent property speculation, to whether sharing can be a form of luxury rather than a compromise. Home Economics presents five These models have been developed new models for domestic life curated in an intensely pragmatic way, through five periods of time. These working with architects, artists, timescales – Hours, Days, Months, developers, filmmakers, financial Years and Decades – correspond institutions and fashion designers. to how long each model is to be It is the first exhibition on called “home”. The projects appear architecture to be curated through as full-scale 1:1 interiors in the time spent in the home, and is British Pavilion, displaying dedicated to exploring alternatives architectural proposals as a direct to conventional domestic architecture. -

House Rules for Public Housing

House Rules for Public Housing The House Rules (“Rules”) of the City of Chandler Housing and Redevelopment Division (the “City’s Housing Office”) are incorporated into the Lease by reference. Tenants agree to comply with the Rules, Admissions and Continued Occupancy Policy (ACOP) and Lease. These Rules are reasonably related to the safety, care and cleanliness of the building, and the safety, comfort and convenience of the tenants. Failure to comply may lead to lease termination. I) CITY OF CHANDLER’S HOUSING RESPONSIBILITIES: A) These Rules will be applied fairly and uniformly to all tenants. B) City’s Housing staff and representatives/designees of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) will inspect each unit at least annually to determine compliance with Uniform Physical Conditions Standards (“UPCS”). Upon completion of an inspection, Housing staff will inform the tenant the specific correction(s) required for unit compliance. If the first inspection finds areas of non-compliance, Housing staff will inform the tenant that training is available if needed for compliance. Housing staff will schedule a second inspection within a reasonable period of time. Failure of a second inspection constitutes a serious violation of the Lease. Housing staff has the right to inspect as many times as it deems necessary, with appropriate notice to the tenant. II) TENANT’S RESPONSIBILITIES: A) The tenant is required to abide by these Rules. Failure to abide by the Rules may result in termination of the Lease. B) OUTSIDE THE UNIT, the tenant must: 1) Keep the yard free of debris and trash. -

Housing, Home, and Health NARRATIVES and HEALTH EQUITY: EXPANDING the CONVERSATION

Housing, home, and health NARRATIVES AND HEALTH EQUITY: EXPANDING THE CONVERSATION A home creates a place where a person can thrive, in the context of a loving family and a welcoming community. For example, housing stability is essential for the well-being of children, the physical condition of homes and the condition of neighborhoods have a direct impact on health, and stable housing helps create social cohesion. The emerging narrative on housing, home, and health helps convey important information about the many ways a place to call home connects to health. Who deserves a place to call home? 1. “Home” is a basic need of every person and every family. 2. Everyone deserves a place to call home, a place to be safe and welcomed, to grow, and to thrive. Everyone deserves a safe, stable home in which to care for one another and provide a place for healing and health. 3. “Place” includes not just “a roof over our heads” but our entire community—to belong includes belonging in a community. a. Healthy communities are places that are welcoming, safe, appealing, and have places to call home for every family. b. When communities thrive, the individual and families in the community are healthier. c. For health equity to be possible, all people and populations need to have access to safe and stable homes in welcoming and thriving communities. Why are homes important for the health of people? 4. A home creates a sense of place. Without a sense of place and belonging, it is impossible to be healthy and to thrive as a human person. -

Euthenics, There Has Not Been As Comprehensive an Analysis of the Direct Connections Between Domestic Science and Eugenics

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics Caleb J. true University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons true, Caleb J., "Eugenothenics: The Literary Connection Between Domesticity and Eugenics" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 730. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/730 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented by CALEB J. TRUE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 2011 History © Copyright by Caleb J. True 2011 All Rights Reserved EUGENOTHENICS: THE LITERARY CONNECTION BETWEEN DOMESTICITY AND EUGENICS A Thesis Presented By Caleb J. True Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________ Laura L. Lovett, Chair _______________________________ Larry Owens, Member _______________________________ Kathy J. Cooke, Member ________________________________ Joye Bowman, Chair, History Department DEDICATION To Kristina. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Laura L. Lovett, for being a staunch supporter of my project, a wonderful mentor and a source of inspiration and encouragement throughout my time in the M.A. -

Chapter 3: Eligibility for Assistance and Occupancy 4350.3 REV-1

4350.3 REV-1 CHAPTER 3. ELIGIBILITY FOR ASSISTANCE AND OCCUPANCY 3-1 Introduction A. This chapter discusses the requirements and procedures for determining whether applicant families may participate in HUD-subsidized multifamily housing programs. Described in this chapter are steps an owner must follow to determine whether a family is eligible to receive assistance in a HUD-subsidized multifamily property and eligible to live in a specific property and unit. These activities are described in a sequential order; however, owners may deviate from this sequence based on project circumstances as long as they determine an applicant’s eligibility before admitting the family to the property. 1. While this chapter provides the rules for eligibility, the processes for developing and maintaining a waiting list and correctly selecting an applicant for the next available unit are addressed in Chapter 4, Sections 3 and 4. Determining and verifying annual income, which is an eligibility requirement, is addressed in Chapter 5. 2. Subsequent chapters in the handbook address activities that occur once an owner determines that a family is eligible for tenancy, such as leasing, recertification, terminations, billing, and reporting. B. This chapter is divided into three sections, each of which identifies the variations in eligibility requirements based upon type of subsidy. The three sections are as follows: • Section 1: Program Eligibility, which describes the criteria by which the owner must determine whether a family is eligible to receive assistance; • Section 2: Project Eligibility, which describes the criteria by which the owner must determine whether a family is eligible to reside in a specific property (e.g., project eligibility limited to a specific population, unit size, and occupancy standards); and • Section 3: Verification of Eligibility Factors, which describes how the owner should collect information to document family composition, disability status, social security numbers, and other factors affecting eligibility for assistance. -

Is Homelessness a Housing Problem?

Housing Policy Debate • Volume 2, Issue 3 937 Is Homelessness a Housing Problem? James D. Wright and Beth A. Rubin Tulane University Abstract Homeless people have been found to exhibit high levels of personal disability (men- tal illness, substance abuse), extreme degrees of social estrangement, and deep poverty. Each of these conditions poses unique housing problems, which are dis- cussed here. In the 1980s, the number of poor people has increased and the supply of low-income housing has dwindled; these trends provide the background against which the homelessness problem has unfolded. Homelessness is indeed a housing problem, first and foremost, but the characteristics of the homeless are such as to make their housing problems atypical. Introduction The question of whether homelessness is a housing problem is per- haps best approached by asking, If homelessness is not a housing problem, then what kind of problem might it be? Most agree that the number of homeless people in the cities increased significantly in the 1980s. Was there any corresponding decline in the availabil- ity of low-cost housing? What besides a dwindling low-income hous- ing supply would account for the trend? Even if one concludes that homelessness is not just a housing problem, there seems to be little doubt that inadequate low-cost housing must have something to do with the problem, and it is useful to ask just what that “something” is. Superficially, the answer to our question is both clearly yes and obviously no. Homeless people, by definition, lack acceptable, cus- tomary housing and must sleep in the streets, double up with friends and family, or avail themselves of temporary overnight shel- ter. -

Recent Developments in State Housing Law

Recent Developments in State Housing Law Wednesday, November 1, 2017 Presenters Betsy Strauss Special Counsel, League of California Cities Barbara Kautz Partner, Goldfarb Lipman Moderator: Jason Rhine Legislative Representative, League of California Cities Goals of the Legislature Strengthen housing element requirement to identify “adequate sites” for RHNA. Connect housing element requirement to identify “adequate sites” to approval of housing development on those sites. Monitor housing element implementation. Maximize Housing Accountability Act effectiveness. Authorize inclusionary rental housing ordinance. Provide state funding for planning and housing production. Housing Accountability Act “The Legislature’s intent in enacting this section in 1982 and in expanding its provisions since then was to significantly increase the approval & construction of new housing for all economic segments of California’s communities by meaningfully and effectively curbing the capability of local governments to deny, reduce the density of, or render infeasible housing development projects. This intent has not been fulfilled.” Applicability Applies to ALL “housing development projects” and emergency shelters: Residences only; Transitional & supportive housing; Mixed use projects with at least 2/3 the square footage designated for residential use. Affordable AND market-rate. All Housing Development Projects If complies with “objective” general plan, zoning, and subdivision standards, can only reduce density or deny if “specific adverse impact” to public health & safety that can’t be mitigated in any other way. (Section 65589.5(j); see Honchariw v. County of Stanislaus (2011).) Any relation to definition of “objective” in SB 35? (Section 65913.4(a)(5).) “Lower density” includes conditions “that have the same effect or impact on the ability of the project to provide housing.” All Housing Development Projects If desire to deny or reduce density: Identify objective standards project does not comply with. -

Housing First in Permanent Supportive Housing

HOUSING FIRST IN PERMANENT SUPPORTIVE HOUSING What is Housing First? Housing First is an approach to quickly and successfully connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness to permanent housing without preconditions and barriers to entry, such as sobriety, treatment or service participation requirements. Supportive services are offered to maximize housing stability and prevent returns to homelessness as opposed to addressing predetermined treatment goals prior to permanent housing entry. Housing First emerged as an alternative to the linear approach in which people experiencing homelessness were required to first participate in and graduate from short-term residential and treatment programs before obtaining permanent housing. In the linear approach, permanent housing was offered only after a person experiencing homelessness could demonstrate that they were “ready” for housing. By contrast, Housing First is premised on the following principles: Homelessness is first and foremost a housing crisis and can be addressed through the provision of safe and affordable housing. All people experiencing homelessness, regardless of their housing history and duration of homelessness, can achieve housing stability in permanent housing. Some may need very little support for a brief period of time, while others may need more intensive and long-term supports. Everyone is “housing ready.” Sobriety, compliance in treatment, or even criminal histories are not necessary to succeed in housing. Rather, homelessness programs and housing providers must be “consumer ready.” Many people experience improvements in quality of life, in the areas of health, mental health, substance use, and employment, as a result of achieving housing. People experiencing homelessness have the right to self-determination and should be treated with dignity and respect. -

Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008

PUBLIC LAW 110–289—JULY 30, 2008 HOUSING AND ECONOMIC RECOVERY ACT OF 2008 VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:57 Sep 03, 2008 Jkt 069139 PO 00289 Frm 00001 Fmt 6579 Sfmt 6579 E:\PUBLAW\PUBL289.110 PUBL289 kgrant on POHRRP4G1 with PUBLAW 122 STAT. 2654 PUBLIC LAW 110–289—JULY 30, 2008 Public Law 110–289 110th Congress An Act July 30, 2008 To provide needed housing reform and for other purposes. [H.R. 3221] Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of Housing and the United States of America in Congress assembled, Economic Recovery Act SECTION. 1. SHORT TITLE; TABLE OF CONTENTS. of 2008. 42 USC 4501 (a) SHORT TITLE.—This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Housing and note. Economic Recovery Act of 2008’’. (b) TABLE OF CONTENT.—The table of contents for this Act is as follows: Sec. 1. Short title; table of contents. DIVISION A—HOUSING FINANCE REFORM Sec. 1001. Short title. Sec. 1002. Definitions. TITLE I—REFORM OF REGULATION OF ENTERPRISES Subtitle A—Improvement of Safety and Soundness Supervision Sec. 1101. Establishment of the Federal Housing Finance Agency. Sec. 1102. Duties and authorities of the Director. Sec. 1103. Federal Housing Finance Oversight Board. Sec. 1104. Authority to require reports by regulated entities. Sec. 1105. Examiners and accountants; authority to contract for reviews of regu- lated entities; ombudsman. Sec. 1106. Assessments. Sec. 1107. Regulations and orders. Sec. 1108. Prudential management and operations standards. Sec. 1109. Review of and authority over enterprise assets and liabilities. Sec. 1110. Risk-based capital requirements. Sec. 1111. -

Cutts, Brenda; and Others House and Home Furnishings Curriculum

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 090 40i CE 001 268 AUTHOR Cutts, Brenda; And Others TITLE House and Home Furnishings Curriculum Guide. Basic Unit, Advanced Unit, and Semester Course. Draft. INSTITUTION CleMson Univ., S.C. Vocational Education Media Center.; South Carolina Si-ate Dept. of Education, Columbia. Office of Vocational Education. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 72p.; For other guides in the unit, see CE 001 266 and 267 and CE 001 269-277 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Consumer Education; Curriculum Development; *Curriculum Guides; Educational Resources; Evaluation Methods; *High School Curriculum; *Home Furnishings; Homemaking Education; *Housing; Learning Experience; *Secondary Grades; Teacher Developed Materials IDENTIFIERS South Carolina ABSTRACT The housing and home furnishings guide, part of a consumer and homemaking education unit, was developed in ,a 3-week curriculum workshop at Winthrop College in June 1972. The identified objectives and learning experiences have been developed with basic reference to developrental tasks, needs, interests, capacities, and prior learning experiences of students. The purpose of the mate ial is to develop an awareness in which the home and its furnishings contribute to a satisfying life through fulfillment of indftAfidual and family goals. The grade 9 basic unit and grade 10 advanced unit consider various aspects of housing and home furnishings. The semester unit4 grades 10-12, examines integration of housing selection factOiS, financial and legal aspects, house plan -

BHA's Section 8 to Homeownership Program Fact Sheet

Boston Housing Authority 52 Chauncy Street 617-988-4000 Boston, Massachusetts 02111-02375 TDD 1-800-545-1833 Ext. 420 BHA’s Section 8 to Homeownership Program Fact Sheet What is the BHA’s Homeownership Program? BHA’s Homeownership Voucher Program is an option for families who are current participants of BHA’s Section 8 Voucher (Housing Choice Voucher, HCV) to use their subsidy towards mortgages, instead of rent. How do I become eligible? • You must meet a number of criteria to be eligible for this program including the following: 1. You must have completed a first time homebuyers program. 2. You must be pre-approved from a lender for a mortgage. 3. You must have 3% of the purchase price of the home available for a down payment, of which 1% must be from your own funds. 4. You, and everyone in your household must be a first time homebuyer, defined as no one in your household may have owned or had ownership interest in any residential property for the past three years. 5. You must have good credit: Lenders typically look for a credit score of at least 650 in reviewing a mortgage application. 6. BHA’s effective payment standard schedule is applied in determining the amount of subsidy your family is eligible for in this program. • Minimum income requirements: o Except in the case of disabled families, the qualified annual income of the adult family members who will own the home must not be less than the Federal minimum hourly wage multiplied by 2,000 hours. o For disabled families, the qualified annual income of the adult family members who will own the home must not be less than the monthly Federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefit for an individual living alone multiplied by 12. -

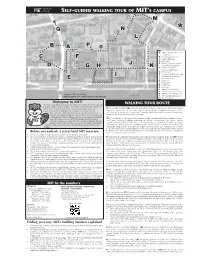

A B C D E F G H I J K L M 0 P

SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF M.....IT’S CAMPUS ... M j .... Q N ....... * L ........ ........... B .....A P.. 0 ... .... Lobby 7 & Visitor Info Center ....... A ..... (77 Mass Ave) C F B Stratton Student Center C Kresge Auditorium .... MIT Chapel D E Building 1 (nearby entrance J to Hart Nautical Gallery) D........ ......... G ..... H K F Building 3/Design & ..... .... Manufacturing display ......... .............................. G Killian Court H Ellen Swallow Richards Lobby I I Hayden Memorial Library E J McDermott Court K Media Lab L North Court ......... M Koch Institute N Stata Center O Edgerton’s Strobe Alley P Memorial Lobby / Barker Library Q 1 smoot = 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) Q MIT Museum (265 Mass Ave) Bridge length = 364.4 smoots, plus or minus one ear MIT Coop/Kendall Square Q* Smoot markings Welcome to MIT! forma- We hope you enjoy your visit! The tour route outlined on this map will WALKING TOUR ROUTEn help you explore MIT’s campus. The Office of Admissions conducts information sessions followed by student-led campus tours for u Leave Lobby 7 (Bldg. 7 [A]) and cross Massachusetts Avenue (Mass Ave). Central and Harvard prospective students and families, Mon–Fri, excluding federal, Squares are up the street to your right, and the Harvard Bridge (leading into Boston) is to your Massachusetts, and Institute holidays and the winter break left. Mass Ave is a main street connecting Cambridge and Boston, and bus stops servicing major period. Info sessions begin at 10 am and 2 pm; campus tours routes can be found on either side of the street.