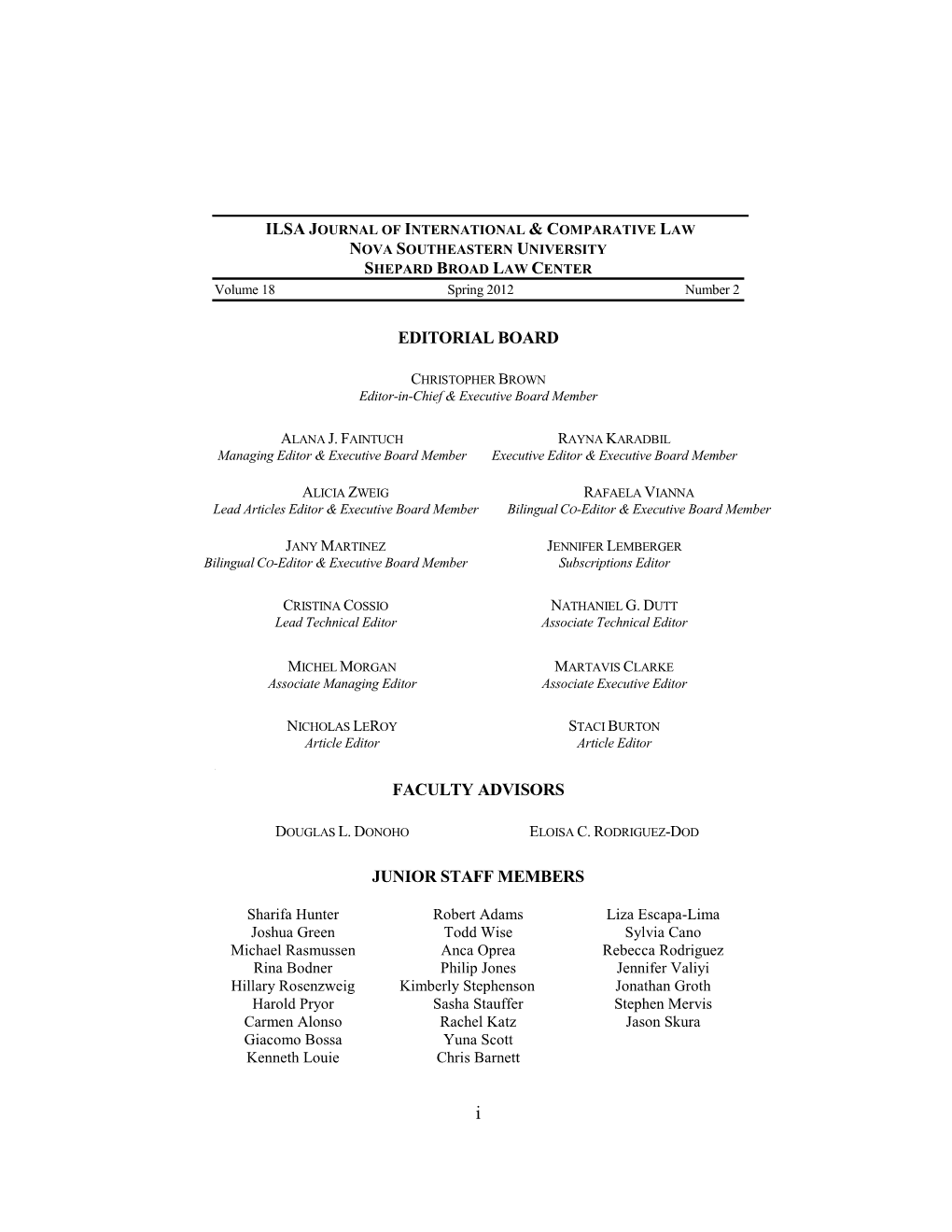

Editorial Board Faculty Advisors Junior Staff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rule of Law in Morocco: a Journey Towards a Better Judiciary Through the Implementation of the 2011 Constitutional Reforms

RULE OF LAW IN MOROCCO: A JOURNEY TOWARDS A BETTER JUDICIARY THROUGH THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE 2011 CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS Norman L. Greene I. OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ........................ 458 A. Rule ofLaw and Judicial Reform ....................... 458 B. What Is a Good JudicialSystem: Basic Principles................459 C. The Key Elements: Independent Structure, Behavior and Education, andAccess ........................... 462 * Copyright C 2012 by Norman L. Greene. The author is a United States lawyer in New York, N.Y. who has written and spoken extensively on judicial reform, including judicial independence; the design of judicial selection systems and codes; and domestic and international concepts of the rule of law. See e.g., Norman L. Greene, The Judicial Independence Through Fair Appointments Act, 34 FORDHAM URB. L.J. 13 (2007) and his other articles referenced below, including Norman L. Greene, How Great Is America's Tolerancefor Judicial Bias? An Inquiry into the Supreme Court's Decisions in Caperton and Citizens United, Their Implicationsfor JudicialElections, and Their Effect on the Rule of Law in the United States, 112 W.VA. L. REV. 873 (2010), and Norman L. Greene, Perspectivesfrom the Rule of Law and InternationalEconomic Development: Are There Lessons for the Reform of Judicial Selection in the United States?, 86 DENV. U. L. REV. 53 (2008). He has previously written a number of articles regarding Morocco, including its judiciary, its history, and Moroccan-American affairs. His earlier article on the Moroccan judiciary was published before the adoption of the 2011 Moroccan constitutional reforms as Norman L. Greene, Morocco: Beyond King's Speech & Constitutional Reform: An Introduction to Implementing a Vision of an Improved Judiciary in Morocco, MOROCCOBOARD NEWS SERVICE (Apr. -

Sailing for Safe Abortion Access: the Emergence of a Conscious Social Nonmovement in Morocco

Sailing for Safe Abortion Access: The Emergence of a Conscious Social Nonmovement in Morocco By Julia Ellis-Kahana In partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Sociology Brown University April 2013 Julia Ellis-Kahana ________________________________ Advisor Carrie Spearin ________________________________ First Reader Michael Kennedy ! ! ! ________________________________! ! ! Disclosures Research for this thesis has been completed with the support of: Royce Fellowship, Swearer Center for Public Service, Brown University, 2012-2013 Barbara Anton Internship Grant, Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women, Brown University, 2012-2013 Alice Rowan Swanson Fellowship, SIT Study Abroad, 2012 Acknowledgements I have so much gratitude for the multiple people who have made this project a reality. Carrie Spearin, my advisor, has been patient and understanding. Her pragmatism has enabled me to keep everything in perspective when I felt overwhelmed. Michael Kennedy is my first reader and his own experience of studying a social movement through engaged ethnography has been integral to the way he has guided my research. He has challenged me by asking the right questions at the right time. I have come to appreciate that both Professor Spearin’s and Professor Kennedy’s concern for my safety during this project was driven by their genuine parental instincts. Kerri Heffernan, the director of the Royce Fellowship Program at the Swearer Center for Public Service, has been an invaluable resource for me. She helped me realize that I needed to assemble a team of people at Brown who would believe in me to complete my research in the Netherlands and Morocco. This group of professors includes Melani Cammett, Rebecca Allen, Ziad Bentahar, Mehrangiz Kar, and John Modell. -

1 Friends of Morocco Quarterly Newsletter July 2018 News From

Friends of Morocco Quarterly Newsletter July 2018 News from Morocco 07/14 Weekly News in Review 07/07 Weekly News in Review 06/23 Weekly News in Review 06/16 Weekly News in Review 06/09 Weekly News in Review 06/02 Weekly News in Review Peace Corps Morocco is celebrating 55 years of service in Morocco (formerly the Staj 100 Celebration) with a media campaign starting this August! The Multimedia Committee is collecting submissions from RPCVs for photos and stories to be shared via Peace Corps Morocco's media channels, including Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. The committee is working with several current PCVs to plan interviews with RPCVs and former staff interested in sharing stories. We are also gathering information for a long-term archival project. Resources of the Friends of Morocco and Peace Corps HQ will also be included. If you interested in sharing photos and stories from your service, fill out our Google Form here. If there is a Moroccan counterpart, staff member, host relative, student, etc., we should feature, submit this form. Please also feel free to contact us at [email protected]. Peace Corps/Morocco to Politics Rick Neal, Morocco 88-93, Candidate for US House of Representatives (OH) joined the Peace Corps after college, working in Morocco for five years as a teacher and a health educator. Rick Neal for U.S. Congress. He writes: I'm running for Congress in Ohio's 15th district against Steve Stivers. It's time we had a Congress that works for all of us - for better-paying jobs, for an end to the opioid epidemic, and for affordable healthcare for everyone. -

Gender Self-Determination Troubles

Gender Self-Determination Troubles by Ido Katri A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Ido Katri 2021 Gender Self-Determination Troubles Ido Katri Doctor of Juridical Science Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2021 Abstract This dissertation explores the growing legal recognition of what has become known as ‘gender self-determination.’ Examining sex reclassification policies on a global scale, I show a shift within sex reclassification policies from the body to the self, from external to internal truth. A right to self-attested gender identity amends the grave breach of autonomy presented by other legal schemes for sex reclassification. To secure autonomy, laws and policies understand gender identity as an inherent and internal feature of the self. Yet, the sovereignty of a right to gender identity is circumscribed by the system of sex classification and its individuating logics, in which one must be stamped with a sex classification to be an autonomous legal subject. To understand this failure, I turn to the legal roots of the concept self-determination by looking to international law, and to the origin moment of legal differentiation, sex assignment at birth. Looking at the limitations of the collective right for state sovereignty allows me to provide a critical account of the inability of a right to gender identity to address systemic harms. Self- attested gender identity inevitably redraws the public/private divide along the contours of the trans body, suggesting a need to examine the apparatus of assigning sex at birth and its pivotal role in both the systemic exclusions of trans people, and in the broader regulation of gender. -

Comptes Consolides Comptes Sociaux Exercice 2019

AFMA COMPTES CONSOLIDES COMPTES SOCIAUX EXERCICE 2019 1 AFMA COMPTES CONSOLIDES 2019 ETAT DE LA SITUATION FINANCIERE CONSOLIDEE ACTIF CONSOLIDE EN DIRHAM 31/12/2019 31/12/2018 Goodwill 50 606 694 50 606 694 Immobilisations incorporelles 2 196 000 249 806 Immobilisations corporelles (*) 56 636 334 15 369 490 Titres mis en équivalence Autres actifs financiers non courants 213 735 213 735 Actifs d’impôts différés 8 912 518 487 044 TOTAL ACTIFS NON COURANTS 118 565 281 66 926 769 Stocks Créances clients nettes 466 605 843 541 422 653 Autres créances courantes nettes 84 929 308 105 710 679 Trésorerie et équivalent de trésorerie 31 042 486 7 748 188 TOTAL ACTIFS COURANTS 582 577 637 654 881 520 TOTAL ACTIF 701 142 918 721 808 289 PASSIF CONSOLIDE EN DIRHAM 31/12/2019 31/12/2018 Capital 10 000 000 10 000 000 Réserves Consolidées -21 487 648 6 139 762 Résultats Consolidés de l’exercice 50 137 351 49 784 426 Capitaux propres part du groupe 38 649 703 65 924 188 Réserves minoritaires -81 935 -91 056 Résultat minoritaire -130 514 27 215 Capitaux propres part des minoritaires -212 449 -63 841 CAPIAUX PROPRES D'ENSEMBLE 38 437 253 65 860 347 Dettes financières non courantes : 70 635 676 7 860 432 -Dont dettes envers les établissements de crédit 4 414 280 7 860 432 -Dont obligations locatives non courantes IFRS 16 66 221 396 Impôt différé passif 164 913 122 500 Total passifs non courants 70 800 589 7 982 932 Provisions courantes 360 976 1 237 517 Dettes financières courantes : 48 625 740 50 315 825 -Dont dettes envers les établissements de crédit 42 -

Morocco: Current Issues

Morocco: Current Issues Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs June 30, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21579 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Morocco: Current Issues Summary The United States government views Morocco as an important ally against terrorism and a free trade partner. Congress appropriates foreign assistance funding for Morocco for counterterrorism and socioeconomic development, including funding in support of a five-year, $697.5 million Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) aid program agreed to in 2007. Congress also reviews and authorizes Moroccan purchases of U.S. defense articles. King Mohammed VI retains supreme political power in Morocco, but has taken some liberalizing steps with uncertain effects. On June 17, the king announced he would submit a new draft constitution to a public referendum on July 1. The proposed constitution, which was drafted by a commission appointed by the king in March, aims to grant greater independence to the prime minister, the legislature, and the judiciary. Nevertheless, under the proposed constitution the king would retain significant executive powers, such as the ability to fire ministers and dissolve the parliament, and he would remain commander-in-chief of the armed forces. U.S. officials have expressed strong support for King Mohammed VI’s reform efforts and for the monarchy. Protests, which have been largely peaceful, have continued, however, with some activists criticizing the king’s control over the reform process and calling for more radical changes to the political system. Authorities have tolerated many of the protests, but in some cases security forces have used violence to disperse demonstrators and have beaten prominent activists. -

GROUPEMENT D'etudes ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LA MEDITERRANEE T GROUPEMENT D'etudes ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LA MEDITERRANÉE

GROUPEMENT D'ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LA MEDITERRANEE t GROUPEMENT D'ETUDES ET DE RECHERCHES SUR LA MEDITERRANÉE L'ANNUAIRE DE LA MEDITERRANÉE 2005 Le Partenariat Euro Méditerranéen: quelle actualité? GERM - Cette Publication est éditée en partenariat avec la Fondation Friedrich EBERT © Groupement d'Etudes et de Recherches; sur la Méditerranée W Dépôt légal : 2006/0591 ISBN: 9981 - 9801 - 9 - 6 IMPRIMERIE EL MAARIF AL JADIDA - RABAT PUBLICATION DU GERM CORRESPONDANCE: B.P. : 8163 -Agence des Nations Unies Agdal-Rabat SITE WEB: www.germ.ma Annuaire GERM L'ANNUAIRE DE LA MEDITERRANÉE LES ORGANES DU GERM COMITÉ EXÉCUTIF DU GERM PRÉSIDENT Habib EL MALKI SECRÉTAIRE GÉNÉRAL Driss KHROUZ SECRÉTAIRES GÉNÉRAUX ADJOINTS Larbi EL HARRA5 Fouad M. AMMOR TRÉSORIER Ahmed BEHA] RELATIONS EXTÉRIEURES karima BENAICH - Mohamed KHACHANI - Ahmed ZEKRl - Mohamed RAMI - Houssine AFKIR RECHERCHES ET ÉTUDES Mohamed BERRIANE RELATIONS AVEC LES UNIVERSITÉS: ]amila HOUFAIDI 5ETTAR - Mohamed KHACHANI CONSEILLERS Aziz CHAKER - Fouad ZAIM - Ali IDRI55I - Mohamed MOHATTANE AliAMAHANE COMITÉ DE RÉDACTION DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION Habib EL MALKI RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF Fouad M. AMMOR Annuaire GERM MEMBRES DU COMITÉ Fouad AMMOR - Aziz HASBI - Mohamed BERRIANE - Jamila HOUDAIFI SETTAR - Fouad ZAIM - Mohamed KHACHANI - Aziz CHAKER, Ahmed ZEKRI - Larabi JAIDI - Mustapha KHAROUFI - Driss KHROUZ Mohamed TOZY - Mohamed MOHATTANE CONSEIL SCIENTIFIQUE Habib El MALKI , Professeur d'Economie, Universté Modamed V Driss KHROUZ, Professeur d'Economie, Universté Modamed V Mohamed BERRIANE, Professeur de Géographie à la faculté des lettres et des Sciences Humaines -Rabat Agda!. ALI IDRISSl, Architecte Aziz HASBI, Professeur, Recteur Université Mohamed V- Rabat Agdal Jamila HOUFAIDI SETTAR, Professeur d'Economie à la Faculté de Droit - Casablanca Mohamed BENNANI, Professeur, Recteur Université Moulay Ismail-Meknès. -

Landscaping Broadcast Media in Morocco: TVM's Viewing Frequency

New Media and Mass Communication www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3267 (Paper) ISSN 2224-3275 (Online) Vol.59, 2017 Landscaping Broadcast Media in Morocco: TVM’s Viewing Frequency, Cultural Normalization Effects, and Reception Patterns among Moroccan Youth: An Integrated Critical Content Analysis Abdelghanie Ennam Assistant Professor, Department of English Studies, Ibn Tofail University, Kenitra, Morocco Abstract This paper approaches the Moroccan broadcast media landscape in the age of globally internetworked digital broadcasting systems through an integrated critical content-analysis of TVM’s viewing frequency, cultural normalization effects, and reception patterns as manifest among Moroccan youth. TVM is short for TV Morocco, a handy English substitute for SNRT (Societé Nationale de Radiodiffusion et de Télévision, National Radio & Television Broadcasting Corporation). The paper, first, presents a succinct historical account of the station’s major stages of institutional and structural evolution since its inception to date. Second, it tries to measure the channel’s degrees of watchability and needs satisfaction partially with a view to clarifying what this study sees as a phenomenon of satellite and digital migration of many Moroccans to foreign broadcast and electronic media outlets. Third, the paper attempts to demonstrate if TVM exerts any consolidating or weakening effects on the cultural identity patterns in Morocco purportedly resulting from an assumed normalization process. These three undertakings are carried out on the basis of a field survey targeting a random sample of 179 Moroccan second and third year students of English Studies at Ibn Tofail University, and an elected set of media approaches like Uses and Gratifications Theory, Social Cognitive Theory, Cultivation Theory, and Cultural Imperialism. -

Marokkos Neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi Startet Mit Einem Deutlich Jüngeren Und Weiblicheren Kabinett

Marokkos neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi startet mit einem deutlich jüngeren und weiblicheren Kabinett Hajo Lanz, Büro Marokko • Die Regierungsbildung in Marokko gestaltete sich schwieriger als zunächst erwartet • Durch das Ausscheiden des Mouvement Populaire aus der früheren Koalition verfügt der Premierminister über keine stabile Mehrheit • Die USFP wird wiederum der Regierung angehören • Das neue Kabinett ist das vermutlich jüngste, in jedem Fall aber weiblichste in der Geschichte des Landes Am 15. Oktober 2007 wurde die neue ma- Was fehlte, war eigentlich nur noch die rokkanische Regierung durch König Mo- Verständigung darauf, wie diese „Re- hamed VI. vereidigt. Zuvor hatten sich die Justierung“ der Regierungszusammenset- Verhandlungen des am 19. September vom zung konkret aussehen sollte. Und genau König ernannten und mit der Regierungs- da gingen die einzelnen Auffassungen doch bildung beauftragten Premierministers Ab- weit auseinander bzw. aneinander vorbei. bas El Fassi als weitaus schwieriger und zä- her gestaltet, als dies zunächst zu erwarten Für den größten Gewinner der Wahlen vom gewesen war. Denn die Grundvorausset- 7. September, Premierminister El Fassi und zungen sind alles andere als schlecht gewe- seiner Istiqlal, stand nie außer Zweifel, die sen: Die Protagonisten und maßgeblichen Zusammenarbeit mit dem größten Wahlver- Träger der letzten Koalitionsregierung (Istiq- lierer, der sozialistischen USFP unter Füh- lal, USFP, PPS, RNI, MP) waren sich einig rung von Mohamed Elyazghi, fortführen zu darüber, die gemeinsame Arbeit, wenn wollen. Nur die USFP selbst war sich da in auch unter neuer Führung und eventuell nicht so einig: Während die Basis den Weg neuer Gewichtung der Portfolios, fortfüh- die Opposition („Diktat der Urne“) präfe- ren zu wollen. -

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking Detainee Policy*

Looking Back to Go Forward: Remaking U.S. Detainee Policy* by James M. Durant, III, Lt Col USAF Deputy Head, Department of Law United States Air Force Academy Frank Anechiarico Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law United States Air Force Academy Maynard-Knox Professor of Government and Law Hamilton College [WEB VERSION] April, 2009 © James Durant, III, Frank Anechiarico * This article does not reflect the views of the Air Force, the United States Department of Defense, or the United States Government. “By mid-1966 the U.S. government had begun to fear for the welfare of American pilots and other prisoners held in Hanoi. Captured in the midst of an undeclared war, these men were labeled war criminals. .Anxious to make certain that they were covered by the Geneva Conventions and not tortured into making ‘confessions’ or brought to trial and executed, U.S. Ambassador-at-Large Averell Harriman asked [ New Yorker correspondent Robert] Shaplen to contact the North Vietnamese.” - Thomas Bass (2009) ++ Introduction This article, first explains why and how detainee policy as applied to those labeled enemy combatants, collapsed and failed by 2008. Second, we argue that the most direct and effective way for the Obama Administration to reassert the rule of law and protect national security in the treatment of detainees is to direct review and prosecution of detainee cases to U.S. Attorneys and adjudication of charges against them to the federal courts. The immediate relevance of this topic is raised by the decision of the Obama Administration to use the federal courts to try Ali Saleh Kahah al-Marri in a (civilian) criminal court. -

Gender Matters: Women As Actors of Change and Sustainable Development in Morocco

ISSUE BRIEF 06.19.20 Gender Matters: Women as Actors of Change and Sustainable Development in Morocco Yamina El Kirat El Allame, Ph.D., Professor, Faculty of Letters & Human Sciences, Mohammed V University In comparison to other countries in Against Women helped encourage the the Middle East and North Africa, the Moroccan feminist movement, leading to Moroccan government has implemented a the launch of feminist journals including considerable number of reforms to improve Lamalif and Thamanya Mars in 1983. In the women’s rights, including a gender quota 1990s, women mobilized around the issue of for parliamentary elections, a revision of reforming the Mudawana. In 1992, a petition the Family Code (the Mudawana), a reform was signed by one million Moroccans, and of the constitution, a law allowing women in 1999, large demonstrations were held in to pass nationality to their children, an Rabat and Casablanca. The reforms to the amendment of the rape law, and a law Mudawana were officially adopted in 2004. criminalizing gender-based violence. The 20 February Movement, associated Despite these reforms, women's rights and with the regional uprisings known as the gender equality have not improved; most “Arab Spring,”1 began with the twenty- of the changes exist on paper, and the legal year-old anonymous journalist student, measures have not been implemented well. Amina Boughalbi. Her message—“I am Moroccan and I will march on the 20th of February because I want freedom and HISTORY OF MOROCCAN WOMEN’S equality for all Moroccans”—mobilized INVOLVEMENT IN SUSTAINABLE several thousand, mainly young, Moroccan Moroccan women have DEVELOPMENT men and women. -

1 Friends of Morocco Quarterly Newsletter January 2019 News

Friends of Morocco Quarterly Newsletter January 2019 News from Morocco (compiled almost weekly by Mhamed El Kadi in Morocco) 01/19 Weekly News in Review 01/12 Weekly News in Review 01/05 Weekly News in Review 12/22 Weekly News in Review 12/15 Weekly News in Review 12/08 Weekly News in Review 12/01 Weekly News in Review Watch here as Peace Corps Morocco's 100th group of trainees swears in as official volunteers! 9K views · November 29, 2018 Video 1:57:41 Staj 100 Volunteers 1 Staj 100 Trainees SWEARING-IN SPEECH, JONAH VANROEKEL 12/20/2018 Peace Corps Morocco page by and for volunteers Peace Corps Morocco YouTube page Peace Corps Morocco Facebook page Peace Corps “Official” government page The Peace Corps Morocco Gender and Development (GAD) Committee reorganized the Google Drive resources to match the new Peace Corps Morocco Project Framework. There’s a resource guide to help you find anything you are looking for specifically, but the folders are now organized to help you browse by type of activity (club, camp, splash activity, etc.) Cooperating to success: a photostory of Oued Ifrane’s weaving women 11/20/2018 by Rachael Diniega An Interdisciplinary Conference on Gender, Identity and Youth Empowerment in Morocco - Dates: March 15 - 16, 2019 as part of the Kennesaw state University Year of Morocco program in Kennesaw, GA (outside Atlanta), As part of KSU’s award-winning Annual Country Study Program, the goal of this international conference is to examine ever-changing Moroccan identities with a special focus on the cultural, economic, political and social agency of young women and men.