Part-Writing Guidelines 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: a Hierarchical Approach Author(S): Timothy A

Yale University Department of Music Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: A Hierarchical Approach Author(s): Timothy A. Johnson Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 117-156 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843946 Accessed: 06-07-2017 19:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Department of Music, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Thu, 06 Jul 2017 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HARMONIC VOCABULARY IN THE MUSIC OF JOHN ADAMS: A HIERARCHICAL APPROACH Timothy A. Johnson Overview Following the minimalist tradition, much of John Adams's' music consists of long passages employing a single set of pitch classes (pcs) usually encompassed by one diatonic set.2 In many of these passages the pcs form a single diatonic triad or seventh chord with no additional pcs. In other passages textural and registral formations imply a single triad or seventh chord, but additional pcs obscure this chord to some degree. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices. -

Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874)

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 3 May 2014 Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874) Piotr Illyich Tchaikovsky Liliya Shamazov (ed. and trans.) Stuyvesant High School, NYC, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Theory Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Tchaikovsky, Piotr Illyich and Shamazov, Liliya (ed. and trans.) (2014) "Concise Manual of Harmony, Intended for the Reading of Spiritual Music in Russia (1874)," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. CONCISE MANUAL OF HARMONY, INTENDED FOR THE READING OF SPIRITUAL MUSIC IN RUSSIA (1874) PIOTR ILLYICH TCHAIKOVSKY he presented study is nothing more than a reduction of my Textbook of Harmony T written for the theoretical course at the Moscow Conservatory. While constructing it, I was led by the desire to facilitate the conscious attitude of choir teachers and Church choir directors towards our Church music, while not interfering by any means into the critical rating of the works of our spiritual music composers. -

The Death and Resurrection of Function

THE DEATH AND RESURRECTION OF FUNCTION A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Gabriel Miller, B.A., M.C.M., M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Gregory Proctor, Advisor Dr. Graeme Boone ________________________ Dr. Lora Gingerich Dobos Advisor Graduate Program in Music Copyright by John Gabriel Miller 2008 ABSTRACT Function is one of those words that everyone understands, yet everyone understands a little differently. Although the impact and pervasiveness of function in tonal theory today is undeniable, a single, unambiguous definition of the term has yet to be agreed upon. So many theorists—Daniel Harrison, Joel Lester, Eytan Agmon, Charles Smith, William Caplin, and Gregory Proctor, to name a few—have so many different nuanced understandings of function that it is nearly impossible for conversations on the subject to be completely understood by all parties. This is because function comprises at least four distinct aspects, which, when all called by the same name, function , create ambiguity, confusion, and contradiction. Part I of the dissertation first illuminates this ambiguity in the term function by giving a historical basis for four different aspects of function, three of which are traced to Riemann, and one of which is traced all the way back to Rameau. A solution to the problem of ambiguity is then proposed: the elimination of the term function . In place of function , four new terms—behavior , kinship , province , and quality —are invoked, each uniquely corresponding to one of the four aspects of function identified. -

Seth Shafer AT2.Shafer.Paper.3 Recurrence and Expectation in the First Movement of Brahms's Third Symphony According to Formal

Seth Shafer AT2.Shafer.paper.3 Recurrence and Expectation in the First Movement of Brahms’s Third Symphony According to formal abstractions describing sonata form since Haydn, the exposition and recapitulation present the listener with several repetitions of similar material, nearly identical in fact, outside of a transposition of the second theme group into the tonic key upon its final statement (see Example 1): Example 1: An abstraction of sonata form showing repetition of musical material. Leonard Meyer addresses the phenomenological experience of listening to repeated material in Emotion and Meaning in Music: The fact that as we listen to music we are constantly revising our opinions of what has happened in the past in the light of present events is important because it means that we are continually altering our expectations. It means, furthermore, that repetition, though it may exist physically, never exists psychologically. Thus, though it may seem a truism, it is of some moment to recognize that the repetition, say, of the exposition section of a sonata-form movement or that of the first-theme group in the recapitulation has quite a different meaning from that communicated by the original statement. (Meyer: 49) Meyer argues that the psychological experience of hearing repeated material generates certain expectations. Those expectations can result in two types of tension for the listener: tension created by large-scale expectations about if or when a sound term will recur after its departure, and tension created by small-scale deviations from a directly reiterated sound term (Meyer: 152). In this paper, I explore the first movement of Brahms’s Third Symphony with not only an eye for repetition, but also an ear for the tension between sonata form expectations and the reality of the Seth Shafer AT2.Shafer.paper.3 piece. -

The Harmonic Cadences

The Harmonicmusic theory Cadences for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush A cadence is generally considered to be the last two chords of a phrase, section or piece. there are four types of cadences, each with their own specific requirements and variations. an authentic cadence consists of a dominant function chord (v or vii) moving to tonic. to be considered a perfect authentic cadence, a cadence must meet all of the following criteria: it must use a v chord if the cadence (not a vii) doesn’t meet *both chords must be all of those in root position criteria, it’s considered to *the soprano must perfect be an imperfect end on the tonic authentic imperfect imperfect authentic authentic *the soprano must authentic move by step cadence! 6 6 * G: V I G: vii° I G: V4 I a plagal cadence consists of a subdominant function chord (iv or ii) moving to tonic. to be considered a perfect plagal cadence, a cadence must meet all of the following criteria: it must use a iv chord if the cadence (not a ii) doesn’t meet *both chords must be all of those in root position criteria, it’s considered to *the soprano must perfect be an end on the tonic plagal imperfectplagal imperfectplagal imperfect *the soprano must plagal keep the common tone cadence! * G: IV I G: IV6 I G: ii I6 a half cadence is any cadence that ends on the dominant chord (v). a specific type of half cadence is the phrygian cadence, which must meet the following criteria: it occurs only in minor half it uses a iv chord moving to v * phrygian phrygian *the soprano and bass move by step in contrary motion G: I V *the soprano and bass both e: iv6 V e: iv V *end on the fifth scale degree a deceptive cadence is a cadence where the dominant chord (V) resolves to something other than tonic.. -

Ii, Or I to Ii6) Greatly Reduces the Danger of Forbidden Parallels and Also Improves the Sound

Music Theory I (MUT 1111) Prof. Nancy Rogers ! ! The Supertonic Chord (ii or ii°) The supertonic is the strongest diatonic pre-dominant. It should therefore progress immediately to V and not move to a weaker pre-dominant such as IV or vi. It is common for the tonic to lead directly to the supertonic, but beware of parallel fifths and octaves! Inverting one of the chords but not the other (i.e., I6 to ii, or I to ii6) greatly reduces the danger of forbidden parallels and also improves the sound. Contrary motion in the outer voices is helpful, although not necessary. Placing an intermediate chord (most notably vi) between the tonic and the supertonic avoids the problems associated with stepwise root motion. Because its root lies a fifth above (or a fourth below) the dominant, the supertonic resolves to the dominant very easily. Root motion by descending fifths, as you will see, produces a very strong sense of progression in most cases — including the exceedingly common ii – V – I (often extended to vi – ii – V – I), a typical way to approach a cadence. Another very common type of root motion is by descending thirds. Because triads whose roots are a third apart share two common tones, such progressions are relatively simple to write. One very common example is I – vi – IV – ii (using all three of the most common pre-dominant chords). The supertonic chord occurs far more often in first inversion (ii6) than in root position. Indeed, in minor keys, ii° cannot be used in root position because, as a general principle, we dislike the sound of root-position diminished 6 ^ ^ triads. -

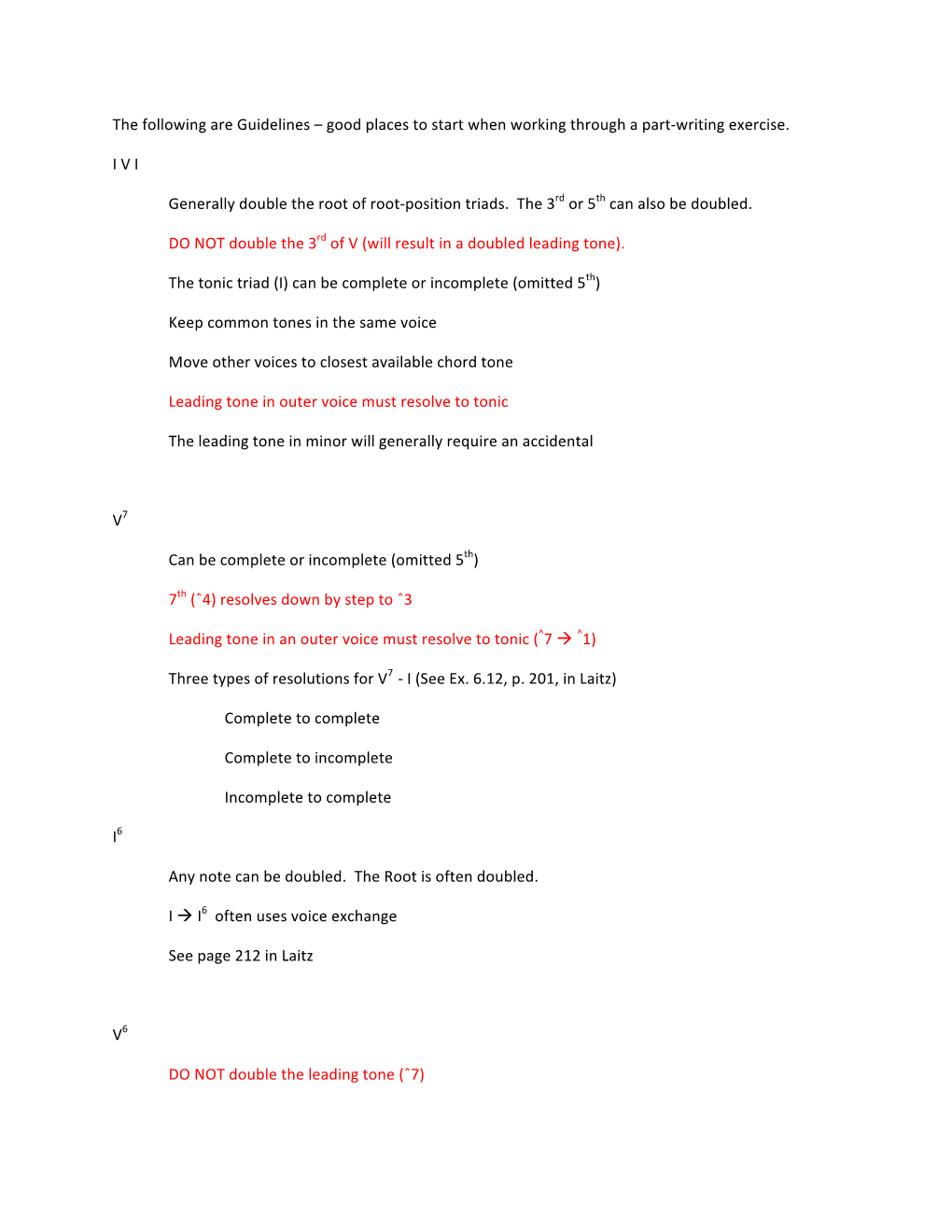

Part-Writing Guidelines

The following are Guidelines – good places to start when working through a part-writing exercise. I V I Generally double the root of root-position triads. The 3rd or 5th can also be doubled. DO NOT double the 3rd of V (will result in a doubled leading tone). The tonic triad (I) can be complete or incomplete (omitted 5th) Keep common tones in the same voice Move other voices to closest available chord tone Leading tone in outer voice must resolve to tonic The leading tone in minor will generally require an accidental V7 Can be complete or incomplete (omitted 5th) 7th (ˆ4) resolves down by step to ˆ3 Leading tone in an outer voice must resolve to tonic (^7 ^1) Three types of resolutions for V7 - I (See Ex. 6.12, p. 134, in Laitz) Complete to complete Complete to incomplete Incomplete to complete I6 Any note can be doubled. The Root is often doubled. I I6 often uses voice exchange See page 145 in Laitz V6 DO NOT double the leading tone (ˆ7) Double the root or the 5th of the chord viio6 Generally double the bass (ˆ2) Never double the leading tone Voice leading ˆ7 always resolves up to ˆ1 ˆ4 often resolves down to ˆ3 See viio6 handout for more details: http://eweb.furman.edu/~dkoppelman/fu/Theory/112/112A/viio6.pdf V7 INVERSIONS Almost always a complete chord 7th (ˆ4) usually resolves down to ˆ3 when moving to I If the leading tone is in the outer voice, then it must resolve to ˆ1 V6/5 I (Resolve the leading tone in the bass up to ^1) V4/2 I6 (Resolve the 7th in the bass down to ^3) V4/3 in the progression I V4/3 I6: upper voice typically -

1 Schubert's Harmonic Language and Fourier Phase Space

Schubert’s Harmonic Language and Fourier Phase Space —Jason Yust The idea of harmonic space is a powerful one, not primarily because it makes visualization of harmonic objects possible, but more fundamentally because it gives us access to a range of metaphors commonly used to explain and interpret harmony: distance, direction, position, paths, boundaries, regions, shape, and so on. From a mathematical perspective, these metaphors are all inherently topological. The most prominent current theoretical approaches involving harmonic spaces are neo- Riemannian theory and voice-leading geometry. Recent neo-Riemannian theory has shown that the Tonnetz is useful for explaining a number of features of the chromatic tonality of the nineteenth century (e.g., Cohn 2012), especially the common-tone principles of Schubert’s most harmonically adventurous progressions and tonal plans (Clark 2011a–b). One of the drawbacks of the Tonnetz, however, is its limited range of objects, which includes only the twenty-four members of one set class. The voice-leading geometries of Callender, Quinn, and Tymoczko 2008 and Tymoczko 2011 also take chords as objects. But because the range of chords is much wider—all chords of a given cardinality, including multisets and not restricted to equal temperament—the mathematical structure of voice-leading geometries is much richer, a continuous geometry as opposed to a discrete network. Yet voice-leading geometries also differ fundamentally from the Tonnetz in what it means for two chords to be close together: in the Tonnetz, nearness is about having a large number of common tones, not the size of the voice leading per se. -

Common-Tone Diminished Seventh Chords

Prof. Nancy Rogers ! COMMON-TONE DIMINISHED SEVENTH CHORDS The common-tone diminished seventh chord is a chromatic non-functional chord that serves to expand another chord. Because it generally appears as a collection of neighbor tones, the common-tone diminished seventh is often described as a “neighbor chord.” The outer voices are especially likely to move by step or common tone; leaps (if necessary) are usually relegated to an inner voice. As its name suggests, the common-tone diminished seventh chord has a fully diminished quality and shares one note with the chord it prolongs. This common tone is the root of the prolonged chord. Since the common-tone diminished seventh chord has no function of its own, it is not given its own Roman numeral but instead is simply abbreviated CT°7. a. preferred b. acceptable c. poor soprano d. poor spelling % & '& & %% & '& & %% & & %% & %(& & $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$" % & ( & & & ( & & & ( & & & ( & & & ' & & & & & & & & & & & % % % % $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$#%& & 7 & % & & 7 & % & & 7 & % & & 7 & B b: I CT° I I CT° I I CT° I I CT° I Notice that the smoothest voice-leading will result in a doubled fifth (a); this is generally considered preferable to leaping, although minimal leaping is acceptable as long as it is hidden in an inner voice (b). Leaping in either of the outer voices is undesirable (c). The common-tone diminished seventh chord’s spelling should be determined by the voice- leading tendencies of the notes involved: examples a-c are spelled appropriately, but d is not. Notice that when the expanded chord is in root position, the CT°7 will appear to be 4 in 2 position. e. f. -

The Neapolitan Triad and the Common-Tone Diminished Seventh

Chapter 21 The Neapolitan Triad and the Common-Tone Diminished Seventh his chapter introduces two frequently encountered chromatic chords. The Neapoli- Ttan is a major triad with a lowered scale degree 2 as its root; it can substitute for a diatonic ii triad in major or minor keys. It most typically appears in first inversion, with scale degree 4 in the bass. The lowered scale degree 2 then sounds in some upper voice and proceeds downward, either directly to the leading tone (if a V chord is what follows) or through scale degree 1 and then to the leading tone (if the dominant harmony is preceded by a cadential six-four or a secondary diminished seventh). The common-tone diminished seventh is frequently used as a colorful harmonic em- bellishment of a major or minor triad or a dominant seventh chord. In such cases the root of the upcoming chord is one of the four notes in the common-tone diminished seventh (the common tone). Try harmonizing just the beginning of “Happy Birthday” with a common-tone diminished seventh chord. In addition to the examples in this chapter, the common-tone diminished seventh is also featured in Examples 22.10 and 24.2. 536 9780199943821_0536_0572_CH21.indd 536 8/8/13 3:18 PM THE NEAPOLITAN TRIAD AND THE COMMON-TONE DIMINISHED SEVENTH 537 THE NEAPOLITAN Example 21.1. Franz Schubert (1797–1828), “Der Müller und der Bach” (opening), from Die schöne Müllerin, op. 25, D. 795 (1824) 9780199943821_0536_0572_CH21.indd 537 8/8/13 3:18 PM 538 THE NEAPOLITAN TRIAD AND THE COMMON-TONE DIMINISHED SEVENTH Translation: Where a true heart perishes from love, There the lilies wilt in every bed; Then the full moon must go into the clouds, So that its tears will not be seen; Then the angels close their eyes And sob and sing his soul to rest.