The Nine-Step Scale of Alexander Tcherepnin: Its Conception, Its Properties, and Its Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Non-Heptatonic Modes

Tagg: Everyday Tonality II — 4. Non‐heptatonic modes 151 4. Non‐heptatonic modes If modes containing seven different scale degrees are heptatonic, eight‐note modes are octatonic, six‐note modes hexatonic, those with five pentatonic, while four‐ and three‐note modes are tetratonic and tritonic. Now, even though the most popular pentatonic modes are sometimes called ‘gapped’ because they contain two scale steps larger than those of the ‘church’ modes of Chapter 3 —doh ré mi sol la and la doh ré mi sol, for example— they are no more incomplete FFBk04Modes2.fm. 2014-09-14,13:57 or empty than the octatonic start to example 70 can be considered cluttered or crowded.1 Ex. 70. Vigneault/Rochon (1973): Je chante pour (octatonic opening phrase) The point is that the most widespread convention for numbering scale degrees (in Europe, the Arab world, India, Java, China, etc.) is, as we’ve seen, heptatonic. So, when expressions like ‘thirdless hexatonic’ occur in this chapter it does not imply that the mode is in any sense deficient: it’s just a matter of using a quasi‐global con‐ vention to designate a particular trait of the mode. Tritonic and tetratonic Tritonic and tetratonic tunes are common in many parts of the world, not least in traditional music from Micronesia and Poly‐ nesia, as well as among the Māori, the Inuit, the Saami and Native Americans of the great plains.2 Tetratonic modes are also found in Christian psalm and response chanting (ex. 71), while the sound of children chanting tritonic taunts can still be heard in playgrounds in many parts of the world (ex. -

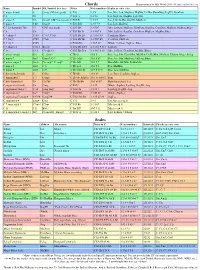

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

Chord Progressions

Chord Progressions Part I 2 Chord Progressions The Best Free Chord Progression Lessons on the Web "The recipe for music is part melody, lyric, rhythm, and harmony (chord progressions). The term chord progression refers to a succession of tones or chords played in a particular order for a specified duration that harmonizes with the melody. Except for styles such as rap and free jazz, chord progressions are an essential building block of contemporary western music establishing the basic framework of a song. If you take a look at a large number of popular songs, you will find that certain combinations of chords are used repeatedly because the individual chords just simply sound good together. I call these popular chord progressions the money chords. These money chord patterns vary in length from one- or two-chord progressions to sequences lasting for the whole song such as the twelve-bar blues and thirty-two bar rhythm changes." (Excerpt from Chord Progressions For Songwriters © 2003 by Richard J. Scott) Every guitarist should have a working knowledge of how these chord progressions are created and used in popular music. Click below for the best in free chord progressions lessons available on the web. Ascending Augmented (I-I+-I6-I7) - - 4 Ascending Bass Lines - - 5 Basic Progressions (I-IV) - - 10 Basie Blues Changes - - 8 Blues Progressions (I-IV-I-V-I) - - 15 Blues With A Bridge - - 36 Bridge Progressions - - 37 Cadences - - 50 Canons - - 44 Circle Progressions -- 53 Classic Rock Progressions (I-bVII-IV) -- 74 Coltrane Changes -- 67 Combination -

Surviving Set Theory: a Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory

Surviving Set Theory: A Pedagogical Game and Cooperative Learning Approach to Undergraduate Post-Tonal Music Theory DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Angela N. Ripley, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: David Clampitt, Advisor Anna Gawboy Johanna Devaney Copyright by Angela N. Ripley 2015 Abstract Undergraduate music students often experience a high learning curve when they first encounter pitch-class set theory, an analytical system very different from those they have studied previously. Students sometimes find the abstractions of integer notation and the mathematical orientation of set theory foreign or even frightening (Kleppinger 2010), and the dissonance of the atonal repertoire studied often engenders their resistance (Root 2010). Pedagogical games can help mitigate student resistance and trepidation. Table games like Bingo (Gillespie 2000) and Poker (Gingerich 1991) have been adapted to suit college-level classes in music theory. Familiar television shows provide another source of pedagogical games; for example, Berry (2008; 2015) adapts the show Survivor to frame a unit on theory fundamentals. However, none of these pedagogical games engage pitch- class set theory during a multi-week unit of study. In my dissertation, I adapt the show Survivor to frame a four-week unit on pitch- class set theory (introducing topics ranging from pitch-class sets to twelve-tone rows) during a sophomore-level theory course. As on the show, students of different achievement levels work together in small groups, or “tribes,” to complete worksheets called “challenges”; however, in an important modification to the structure of the show, no students are voted out of their tribes. -

ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN and HIS STUDENTS STEPHEN GOSLING, Pianist

ALEXANDER TCHEREPNIN Born in St. Petersburg in 1899, Alexander Tcherepnin became a true musical citizen of the world. With the cen- ter of his career shifting from Tbilisi and the Caucasus to Paris and central Europe, from Shanghai and Tokyo to Brussels and back to Paris, and ultimately from Chicago and New York to London and Zurich, he left an indeli- ble influence, transcending barriers of nationality and generation. Tcherepnin’s gifts were hereditary. His father Nicholas Tcherepnin had composed impressionistic ballets that won the Diaghilev troupe its first Western successes. When the nineteen-year-old Alexander belatedly be- gan formal conservatory studies of musical theory, he had already written some two hundred piano pieces, many with modernistic traits inspired by his father’s star pupil Sergei Prokofiev. Young Tcherepnin brought these to Tbilisi, where the family relocated during the revolutionary turmoil of 1918, often performing them in recital (several dozen of these early efforts became best-sellers when published in Paris after he settled there in 1921). In Georgia, Alexander began composing on synthetic scales derived from the “major-minor triad” (C-Eb-E-G). Nikolai had explored the eight-step “octotonic” scale, which regularly alternates half-steps and whole-steps; Alexander went his father one better: by 1922 he was developing a vocabulary of ear-catching sounds from his own symmetrical nine-step scale (C-Db-Eb-E-F-G-Ab-A-B-C—the interval pattern is half-whole-half; half-whole-half; half-whole-half). Further experiments during final studies at the Paris Conser- vatoire yielded an approach called “Interpoint,” meant to convey complex rhythmic information with maximum clarity, and to keep the various musical registers separate in the ear. -

Teaching Guide: Area of Study 7

Teaching guide: Area of study 7 – Art music since 1910 This resource is a teaching guide for Area of Study 7 (Art music since 1910) for our A-level Music specification (7272). Teachers and students will find explanations and examples of all the musical elements required for the Listening section of the examination, as well as examples for listening and composing activities and suggestions for further listening to aid responses to the essay questions. Glossary The list below includes terms found in the specification, arranged into musical elements, together with some examples. Melody Modes of limited transposition Messiaen’s melodic and harmonic language is based upon the seven modes of limited transposition. These scales divide the octave into different arrangements of semitones, tones and minor or major thirds which are unlike tonal scales, medieval modes (such as Dorian or Phrygian) or serial tone rows all of which can be transposed twelve times. They are distinctive in that they: • have varying numbers of pitches (Mode 1 contains six, Mode 2 has eight and Mode 7 has ten) • divide the octave in half (the augmented 4th being the point of symmetry - except in Mode 3) • can be transposed a limited number of times (Mode 1 has two, Mode 2 has three) Example: Quartet for the End of Time (movement 2) letter G to H (violin and ‘cello) Mode 3 Whole tone scale A scale where the notes are all one tone apart. Only two such scales exist: Shostakovich uses part of this scale in String Quartet No.8 (fig. 4 in the 1st mvt.) and Messiaen in the 6th movement of Quartet for the End of Time. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications

Generalized Interval System and Its Applications Minseon Song May 17, 2014 Abstract Transformational theory is a modern branch of music theory developed by David Lewin. This theory focuses on the transformation of musical objects rather than the objects them- selves to find meaningful patterns in both tonal and atonal music. A generalized interval system is an integral part of transformational theory. It takes the concept of an interval, most commonly used with pitches, and through the application of group theory, generalizes beyond pitches. In this paper we examine generalized interval systems, beginning with the definition, then exploring the ways they can be transformed, and finally explaining com- monly used musical transformation techniques with ideas from group theory. We then apply the the tools given to both tonal and atonal music. A basic understanding of group theory and post tonal music theory will be useful in fully understanding this paper. Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 A Crash Course in Music Theory 2 3 Introduction to the Generalized Interval System 8 4 Transforming GISs 11 5 Developmental Techniques in GIS 13 5.1 Transpositions . 14 5.2 Interval Preserving Functions . 16 5.3 Inversion Functions . 18 5.4 Interval Reversing Functions . 23 6 Rhythmic GIS 24 7 Application of GIS 28 7.1 Analysis of Atonal Music . 28 7.1.1 Luigi Dallapiccola: Quaderno Musicale di Annalibera, No. 3 . 29 7.1.2 Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kreuzspiel, Part 1 . 34 7.2 Analysis of Tonal Music: Der Spiegel Duet . 38 8 Conclusion 41 A Just Intonation 44 1 1 Introduction David Lewin(1933 - 2003) is an American music theorist.