Music Theory for Young Students Designed for Use in Creative Music Theory Classes in the Preparatory Division

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harmonizing Notes Outside the Prevailing Harmony

Krumbholz, Theory IV Harmonizing Melody Notes Outside the Prevailing Harmony. 1 More than one solution may work with a particular “nonchord” note. Experiment with different harmonizations. Note: several of the chords below may be enharmonically spelled, for ease of reading (for the performer). Use a seventh chord whose root lies a P5 above/below the prevailing harmony: Use a barbershop seventh chord (BS 7) whose root is a m2 below/above the prevailing harmony. Works especially well when the prevailing harmony is a BS 7. Use a BS 7 chord whose root lies a M3 below the prevailing chord: 1 Based on handouts from Burt Szabo and Dave Stevens. Krumbholz, Harmonizing Nonchord tones, p. 2 Use a BS 7 chord that lies a tritone away (“across the clock”) from the prevailing harmony. Use a chord that has the same root as the prevailing harmony • The added 9 th chord, major triads only (I or IV chord only) • The incomplete (or barbershop) 9 th chord; use when the prevailing harmony is a BS 7 chord. • The barbershop (or “substitute”) 6th chord; use when the prevailing harmony is a triad (I or IV chord only). • The barbershop (or “substitute”) 13 th chord; use when the prevailing harmony is a BS 7 chord. Krumbholz, Harmonizing Nonchord tones, p. 3 Use a diminished chord with the same root as the prevailing chord. Works especially well when the prevailing harmony is a BS 7 chord. When a “nonchord tone” falls between two harmonies (such as, say, the last note of a measure), the note will be easier to harmonize if you use the above approaches as applied to the upcoming chord rather than the current one. -

Hummi-Com: Humming-Based Music Composition System

Hummi-Com: Humming-based Music Composition System Tetsuro Kitahara, Syohei Kimura, Yuu Suzuki, and Tomofumi Suzuki College of Humanities and Science, Nihon University 3-25-40, Sakurajosui, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-8550, Japan [email protected] ABSTRACT designed from music theory to avoid musically inappropriate In this paper, we propose a composition-by-humming sys- melodies. tem, called Hummi-Com, that automatically corrects musi- cally inappropriate notes. Although various systems with a 2. ISSUES AND KEY CONCEPT composition-by-humming function have been developed, it is Because our system targets musically unskilled people difficult in practice for non-musicians to compose musically such as those who do not play an instrument, we assume appropriate melodies with these systems due to the target that the audio signals hummed by users contain notes with user's insufficient skill at controlling pitch. In this paper, incorrect pitches because such users are expected to have a we propose note correction rules for avoiding such musically relatively low pitch control skill when humming. When such inappropriate outputs. This rule set is designed based on users try to hum an original melody, the following phenom- the idea of searching for a reasonable trade-off between re- ena often occur: moving dissonant nonchord tones and retaining musically acceptable nonchord tones. 1. The boundaries between notes tend to be unclear be- cause the pitch is unstable. Categories and Subject Descriptors 2. The pitch cannot be correctly converted to a discrete note scale because the pitch tends to be ambiguous H.5,5 [Information Interfaces and Interaction]: Sound (e.g., between C and C]). -

Stephen Brien

AN INVESTIGATION OF FORWARD MOTION AS AN ANALYTIC TEMPLATE (~., ·~ · · STEPHEN BRIEN A THESIS S B~LITTED I P RTIAL F LFLLLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF M IC PERFORMANCE SYDNEY CONSERV ATORIUM OF MUSIC UN IVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to thank Dick Montz, Craig Scott, Phil Slater and Dale Barlow for their support and encouragement in the writing of this thesis. :.~~,'I 1 lt,·,{l ((.. v <'oo'5 ( ., '. ,. ~.r To Hal Galper ABSTRACT Investigati on of Forward Motion as an analytic templ ate extracts the elements of Forward Motion as expounded in jazz pianist Hal Gal per's book- Forward Motion .from Bach to Bebop; a Corrective Approach to Jazz Phrasing and uses these element s as an analyt ic template wi th which to assess fo ur solos of Australian jazz musician Dale Barlow. This case study includes a statistical analysis of the Forward Motion elements inherent in Barlow' s improvisi ng, whi ch provides an interesting insight into how much of Galp er' s educational theory exists within the playing of a mu sician un fa miliar with Galper ' s methods. TABLES CONT ... 9. Table 2G 2 10. Table 2H 26 II . Table21 27 12. Table 2J 28 13 . Table2K 29 14. Table 2L 30 15. Table 2M 3 1 16. Table 2N 32 17. Table 20 33 18. Table 2P 35 19. Table 2Q 36 Angel Eyes I. Table lA 37 2. Table IB 37 3. Table 2A 38 4. Table 2B 40 5. Table 2C 42 6. -

Glossary of Musical Terms PDF - Ricmedia Guitar

Glossary of musical terms PDF - Ricmedia Guitar Glossary of musical terms PDF Compliments of Ricmedia Guitar guitar.ricmedia.com Copyright © Ricmedia A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A Accent A beat or note that is significantly louder than the others Action The space or distance between the fretboard and strings usually of a guitar Acoustic An instrument that creates it’s own amplification by passive means, not electric Ad Lib (Ad Libitum) Musical directive that gives the musician the ability to improvise or omit a section of music Arpeggio A series of notes derived from a chord, aka: broken chord Augmented Any note that has been raised by a semitone from it’s normal position B Banjo A stringed instrument characterized by a round body and a unique twangy sound Bass Mosty referring to a bass guitar but can be referencing to any instrument in the bass tonal range Bass Clef A musical symbol that indicates the piece should be played in the bass tonal range, or F clef Bass Drum Generally the largest drum in a drummers kit that sits on it’s side and is played via a foot pedal Beat The main pulse of the music, the rhythm of the music Blue Note Generally referring the the sharp fourth/flat fifth in the blues scale, aka: tritone Blues file:///I|/guitar.ricmedia.com/Cat_Miscellaneous/Music-glossary/glossary-of-musical-terms.html[21/07/2013 4:48:07 PM] Glossary of musical terms PDF - Ricmedia Guitar A large genre of music characterized by strong rhythms, improvisation and guitar centric music Brass The name given to a large range -

02-11-Nonchordtones.Pdf

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.11 Nonchord Tones Nonchord tones = notes that aren't part of the chord. Nonchord tones always embellish/decorate chord tones. Keep in mind that many authors use the term "consonance" for a chord tone, and "dissonance" for a nonchord tone. suspension (S) = "delayed step down" passing tone (PT) neighbor tone (NT) 1. Starts as chord tone, then becomes... PTs are approached and NTs are approached and 2. Nonchord tone metrically accented, left by step in the left by step in different 3. ...then resolves down by step same direction. directions. Common types: 7-6, 4-3, 9-8, 2-3 Preparation Suspension Resolution C:IV6 I escape tone (esc.) retardation (R) -"step-leap" 1. Starts as chord tone, then becomes... appoggiatura (app.) -"leap-step" -to escape, you "step to window, 2. Nonchord tone metrically accented leap out" 3. ...then resolves up by step -may be metrically accented or unaccented -may be metrically accented or unaccented "DELAYED STEP UP" -sometimes called "incomplete neighbor tone" -also sometimes called "incomplete Preparation Retardation Resolution neighbor tone" vii°6 I anticipation (ant.) cambiata (c) -- LESS COMMON -approached by leap or step -also called "changing tone" from either direction -connect 2 consonances a 3rd apart -unaccented (i.e. C-A in this example) neighbor group (n gr.) -must be a chord tone in the -only the 2nd note of the pattern is -upper and lower neighbor together next harmony a dissonance -can also be lower neighbor -may or may not be tied into -specific pattern shown below followed by upper neighbor the resolution note -common in 15th and 16th centuries vii°6 I pedal point or pedal tone (bottom C in left hand) from Bach, WTC, Fugue I in C, m. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music

Affordant Chord Transitions in Selected Guitar-Driven Popular Music Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gary Yim, B.Mus. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: David Huron, Advisor Marc Ainger Graeme Boone Copyright by Gary Yim 2011 Abstract It is proposed that two different harmonic systems govern the sequences of chords in popular music: affordant harmony and functional harmony. Affordant chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions that minimize technical difficulty when performed on the guitar, while functional chord transitions favor chords and chord transitions based on a chord's harmonic function within a key. A corpus analysis is used to compare the two harmonic systems in influencing chord transitions, by encoding each song in two different ways. Songs in the corpus are encoded with their absolute chord names (such as “Cm”) to best represent affordant factors in the chord transitions. These same songs are also encoded with their Roman numerals to represent functional factors in the chord transitions. The total entropy within the corpus for both encodings are calculated, and it is argued that the encoding with the lower entropy value corresponds with a harmonic system that more greatly influences the chord transitions. It is predicted that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional harmony, and therefore a lower entropy value for the letter-name encoding is expected. But, contrary to expectations, a lower entropy value for the Roman numeral encoding was found. Thus, the results are not consistent with the hypothesis that affordant chord transitions play a greater role than functional chord transitions. -

Music Theory for Young Students

Longy School of Music Music Theory for young students designed for use in Creative Music Theory classes in the Preparatory Division by John Morrison Emily Romm Jeremy Van Buskirk Vartan Aghababian Teen Theory I and II second revision fall 2011 © 2011 Longy School of Music of Bard College The creation of this text was supported over a four-year period by the generous donation of Mr. John Carey. Introduction Dear student! You are about to start learning music theory. Music theory is a study of music; it helps to understand how music works. It will teach you to read, write, and compose music. What is music? It is something that can change your mood, make you move faster or slower, it can even change your heartbeat! Music can make you imagine things, sometime nice and sometimes scary, and when it gets stuck in your head, it simply won’t leave! It is everywhere – on the radio, in a concert hall, in church or temple, in school – but it only lives while it sounds. You need a composer to make music, a performer to play it, and a listener to enjoy it. To students, parents, and private instructors: This portion of the theory text, where we explain and demonstrate basic concepts of music theory, is the same in Levels 1, 2, and 3 of the text for Creative Music Theory classes at Longy. As such, it will go further than a student in Level 1 will progress during a year. It will allow those starting their study of music theory at Level 2 or 3 to have all the background information they will need for a solid start in theory. -

Identification and Analysis of Wes Montgomery's Solo Phrases Used in 'West Coast Blues'

Identification and analysis of Wes Montgomery's solo phrases used in ‘West Coast Blues ’ Joshua Hindmarsh A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music The University of Sydney 2016 Declaration I, Joshua Hindmarsh hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person except for the co-authored publication submitted and where acknowledged in the text. This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a higher degree. Signed: Date: 4/4/2016 Acknowledgments I wish to extend my sincere gratitude to the following people for their support and guidance: Mr Phillip Slater, Mr Craig Scott, Prof. Anna Reid, Mr Steve Brien, and Dr Helen Mitchell. Special acknowledgement and thanks must go to Dr Lyle Croyle and Dr Clare Mariskind for their guidance and help with editing this research. I am humbled by the knowledge of such great minds and the grand ideas that have been shared with me, without which this thesis would never be possible. Abstract The thesis investigates Wes Montgomery's improvisational style, with the aim of uncovering the inner workings of Montgomery's improvisational process, specifically his sequencing and placement of musical elements on a phrase by phrase basis. The material chosen for this project is Montgomery's composition 'West Coast Blues' , a tune that employs 3/4 meter and a variety of chordal backgrounds and moving key centers, and which is historically regarded as a breakthrough recording for modern jazz guitar. -

Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: a Hierarchical Approach Author(S): Timothy A

Yale University Department of Music Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: A Hierarchical Approach Author(s): Timothy A. Johnson Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 117-156 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843946 Accessed: 06-07-2017 19:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Department of Music, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Thu, 06 Jul 2017 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HARMONIC VOCABULARY IN THE MUSIC OF JOHN ADAMS: A HIERARCHICAL APPROACH Timothy A. Johnson Overview Following the minimalist tradition, much of John Adams's' music consists of long passages employing a single set of pitch classes (pcs) usually encompassed by one diatonic set.2 In many of these passages the pcs form a single diatonic triad or seventh chord with no additional pcs. In other passages textural and registral formations imply a single triad or seventh chord, but additional pcs obscure this chord to some degree. -

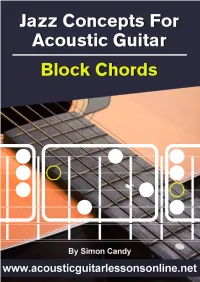

Jazz Concepts for Acoustic Guitar Block Chords

Jazz Concepts For Acoustic Guitar Block Chords © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !2 Table Of Contents A Little Jazz? 4 What Are Block Chords? 4 Chords And Inversions 5 The 3 Main Block Chord Types And How They Fit On The Fretboard 6 Major 7th ...................................................................................6 Dominant 7th ..............................................................................6 Block Chord Application 1 - Blues 8 Background ................................................................................8 Organising Dominant Block Chords On The Fretboard .......................8 Blues Example ...........................................................................10 Block Chord Application 2 - Neighbour Chords 11 Background ...............................................................................11 The Progression .........................................................................11 Neighbour Chord Example ...........................................................12 Block Chord Application 3 - Altered Dominant Block Chords 13 Background ...............................................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Chart .....................................................13 Altered Dominant Chord Example .................................................15 What’s Next? 17 © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Page !3 A Little Jazz? This ebook is not necessarily for jazz guitar players. In fact, it’s more for acoustic guitarists who would like to inject a little -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices.