Ii, Or I to Ii6) Greatly Reduces the Danger of Forbidden Parallels and Also Improves the Sound

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

To View a Few Sample Pages of 30 Days to Better Jazz Guitar Comping

You will also find that you sometimes need to make big jumps across the neck to keep bass lines going. Keeping a solid bass line is more important than smooth voice leading. For example it’s more important to keep a bass line constantly going using simple chords rather than trying to find the hippest chords you know Day 24: Comping with Bass Lines After learning how to use a bass line with chords in the bossa nova, today’s lesson is about how to comp with bass lines in a more traditional jazz setting. Background on Comping with Bass Lines An essential comping technique that every guitarist learns at some point is to comp with bass lines. The two most important ingredients to this comping style are the feel and the bass line. As Joe Pass says “A good bass line must be able to stand by itself”, meaning that you add the chords where you can. Like many other subjects in this book, bass lines could fill up an entire book of their own, but this section will teach you the fundamental principles such as how to construct a bass line and apply it over the ii-V-I progression. What Chords Should I Use? As with bossa nova comping, it’s best to use simple voicings that are easy to grab to keep the bass line flowing as smoothly as possible. The chord diagram below shows the chords that are going to be used, notice that these are all simple inversions with no extensions, but they give the ear enough information to recognize the chord type and have roots on the bottom two strings. -

Discover Seventh Chords

Seventh Chords Stack of Thirds - Begin with a major or natural minor scale (use raised leading tone for chords based on ^5 and ^7) - Build a four note stack of thirds on each note within the given key - Identify the characteristic intervals of each of the seventh chords w w w w w w w w % w w w w w w w Mw/M7 mw/m7 m/m7 M/M7 M/m7 m/m7 d/m7 w w w w w w % w w w w #w w #w mw/m7 d/wm7 Mw/M7 m/m7 M/m7 M/M7 d/d7 Seventh Chord Quality - Five common seventh chord types in diatonic music: * Major: Major Triad - Major 7th (M3 - m3 - M3) * Dominant: Major Triad - minor 7th (M3 - m3 - m3) * Minor: minor triad - minor 7th (m3 - M3 - m3) * Half-Diminished: diminished triad - minor 3rd (m3 - m3 - M3) * Diminished: diminished triad - diminished 7th (m3 - m3 - m3) - In the Major Scale (all major scales!) * Major 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 2, 3, 6 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 - In the Minor Scale (all minor scales!) with a raised leading tone for chords on ^5 and ^7 * Major 7th on scale degrees 3 & 6 * Minor 7th on scale degrees 1 & 4 * Dominant 7th on scale degree 5 * Half-Diminished 7th on scale degree 2 * Diminished 7th on scale degree 7 Using Roman Numerals for Triads - Roman Numeral labels allow us to identify any seventh chord within a given key. -

Music in Theory and Practice

CHAPTER 4 Chords Harmony Primary Triads Roman Numerals TOPICS Chord Triad Position Simple Position Triad Root Position Third Inversion Tertian First Inversion Realization Root Second Inversion Macro Analysis Major Triad Seventh Chords Circle Progression Minor Triad Organum Leading-Tone Progression Diminished Triad Figured Bass Lead Sheet or Fake Sheet Augmented Triad IMPORTANT In the previous chapter, pairs of pitches were assigned specifi c names for identifi cation CONCEPTS purposes. The phenomenon of tones sounding simultaneously frequently includes group- ings of three, four, or more pitches. As with intervals, identifi cation names are assigned to larger tone groupings with specifi c symbols. Harmony is the musical result of tones sounding together. Whereas melody implies the Harmony linear or horizontal aspect of music, harmony refers to the vertical dimension of music. A chord is a harmonic unit with at least three different tones sounding simultaneously. Chord The term includes all possible such sonorities. Figure 4.1 #w w w w w bw & w w w bww w ww w w w w w w w‹ Strictly speaking, a triad is any three-tone chord. However, since western European music Triad of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries is tertian (chords containing a super- position of harmonic thirds), the term has come to be limited to a three-note chord built in superposed thirds. The term root refers to the note on which a triad is built. “C major triad” refers to a major Triad Root triad whose root is C. The root is the pitch from which a triad is generated. 73 3711_ben01877_Ch04pp73-94.indd 73 4/10/08 3:58:19 PM Four types of triads are in common use. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

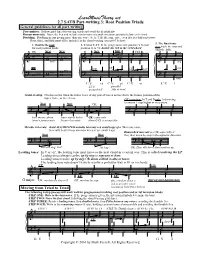

Root Position Triads Part-Writing

LearnMusicTheory.net 2.7 SATB Part-writing 3: Root Position Triads General guidelines for all part-writing Prerequisites. Follow guidelines for voicing triads and avoid the fiendish five. Roman numerals: Name the key and include roman numerals with inversion symbols below each chord. Doubling: Doubling means giving more than one voice (S, A, T, B) the same note, even if it is a different octave. Root, third, and fifth must all be included in the chord voicing (except #3 below). 3. The final tonic 1. Double the root 2. V-vi or V-VI: In the progression root position V to root may triple the root and for root position triads. position vi or VI, double the 3rd in the vi/VI chord. omit the fifth. OK NO! NO! NO! NO! YES 3rd! root root 5th! 3rd! 3rd LT! LT LT 3rd! root 5th! 3rd! root root C:V vi C:V vi C:V vi C:V I LT is parallel unresolved! 5ths & 8ves! Avoid overlap. Overlap occurs when the lower voice of any pair of voices moves above the former position of the upper voice, or vice-versa. OK exception: In T and B only, 3rd moving to unison 1 step higher or vice-versa NO! NO! OK bass moves above tenor moves below OK: same note tenor's former note former bass note (here C-C) is acceptable Melodic intervals: Avoid AUGMENTED melodic intervals and avoid leaps of a 7th in one voice. Generally best to keep common tones or use small leaps. Diminished intervals are OK, especially if NO! NO! they then move by step in the opposite direction. -

Graduate Music Theory Exam Preparation Guidelines

Graduate Theory Entrance Exam Information and Practice Materials 2016 Summer Update Purpose The AU Graduate Theory Entrance Exam assesses student mastery of the undergraduate core curriculum in theory. The purpose of the exam is to ensure that incoming graduate students are well prepared for advanced studies in theory. If students do not take and pass all portions of the exam with a 70% or higher, they must satisfactorily complete remedial coursework before enrolling in any graduate-level theory class. Scheduling The exam is typically held 8:00 a.m.-12:00 p.m. on the Thursday just prior to the start of fall semester classes. Check with the Music Department Office for confirmation of exact dates/times. Exam format The written exam will begin at 8:00 with aural skills (intervals, sonorities, melodic and harmonic dictation) You will have until 10:30 to complete the remainder of the written exam (including four- part realization, harmonization, analysis, etc.) You will sign up for individual sight-singing tests, to begin directly after the written exam Activities and Skills Aural identification of intervals and sonorities Dictation and sight-singing of tonal melodies (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate both pitch and rhythm. Dictation of tonal harmonic progressions (both diatonic and chromatic). Notate soprano, bass, and roman numerals. Multiple choice Short answer Realization of a figured bass (four-part voice leading) Harmonization of a given melody (four-part voice leading) Harmonic analysis using roman numerals 1 Content -

Figured-Bass Notation

MU 182: Theory II R. Vigil FIGURED-BASS NOTATION General In common-practice tonal music, chords are generally understood in two different ways. On the one hand, they can be seen as triadic structures emanating from a generative root . In this system, a root-position triad is understood as the "ideal" or "original" form, and other forms are understood as inversions , where the root has been placed above one of the other chord tones. This approach emphasizes the structural similarity of chords that share a common root (a first- inversion C major triad and a root-position C major triad are both C major triads). This type of thinking is represented analytically in the practice of applying Roman numerals to various chords within a given key - all chords with allegiance to the same Roman numeral are understood to be related, regardless of inversion and voicing, texture, etc. On the other hand, chords can be understood as vertical arrangements of tones above a given bass . This system is not based on a judgment as to the primacy of any particular chordal arrangement over another. Rather, it is simply a descriptive mechanism, for identifying what notes are present in addition to the bass. In this regime, chords are described in terms of the simplest possible arrangement of those notes as intervals above the bass. The intervals are represented as Arabic numerals (figures), and the resulting nomenclatural system is known as figured bass . Terminological Distinctions Between Roman Numeral Versus Figured Bass Approaches When dealing with Roman numerals, everything is understood in relation to the root; therefore, the components of a triad are the root, the third, and the fifth. -

Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: a Hierarchical Approach Author(S): Timothy A

Yale University Department of Music Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: A Hierarchical Approach Author(s): Timothy A. Johnson Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 117-156 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843946 Accessed: 06-07-2017 19:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Department of Music, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Thu, 06 Jul 2017 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HARMONIC VOCABULARY IN THE MUSIC OF JOHN ADAMS: A HIERARCHICAL APPROACH Timothy A. Johnson Overview Following the minimalist tradition, much of John Adams's' music consists of long passages employing a single set of pitch classes (pcs) usually encompassed by one diatonic set.2 In many of these passages the pcs form a single diatonic triad or seventh chord with no additional pcs. In other passages textural and registral formations imply a single triad or seventh chord, but additional pcs obscure this chord to some degree. -

Transfer Theory Placement Exam Guide (Pdf)

2016-17 GRADUATE/ transfer THEORY PLACEMENT EXAM guide! Texas woman’s university ! ! 1 2016-17 GRADUATE/transferTHEORY PLACEMENTEXAMguide This! guide is meant to help graduate and transfer students prepare for the Graduate/ Transfer Theory Placement Exam. This evaluation is meant to ensure that students have competence in basic tonal harmony. There are two parts to the exam: written and aural. Part One: Written Part Two: Aural ‣ Four voice part-writing to a ‣ Melodic dictation of a given figured bass diatonic melody ‣ Harmonic analysis using ‣ Harmonic Dictation of a Roman numerals diatonic progression, ‣ Transpose a notated notating the soprano, bass, passage to a new key and Roman numerals ‣ Harmonization of a simple ‣ Sightsinging of a melody diatonic melody that contains some functional chromaticism ! Students must achieve a 75% on both the aural and written components of the exam. If a passing score is not received on one or both sections of the exam, the student may be !required to take remedial coursework. Recommended review materials include most of the commonly used undergraduate music theory texts such as: Tonal Harmony by Koska, Payne, and Almén, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning and Marvin, and Harmony in Context by Francoli. The exam is given prior to the beginning of both the Fall and Spring Semesters. Please check the TWU MUSIc website (www.twu.edu/music) ! for the exact date and time. ! For further information, contact: Dr. Paul Thomas Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition [email protected] 2 2016-17 ! ! ! ! table of Contents ! ! ! ! ! 04 Part-Writing ! ! ! ! ! 08 melody harmonization ! ! ! ! ! 13 transposition ! ! ! ! ! 17 Analysis ! ! ! ! ! 21 melodic dictation ! ! ! ! ! harmonic dictation ! 24 ! ! ! ! Sightsinging examples ! 28 ! ! ! 31 terms ! ! ! ! ! 32 online resources ! 3 PART-Writing Part-writing !Realize the following figured bass in four voices.