What Are S-Parameters, Anyway? Scattering Parameters Offer an Alternative to Impedance Parameters for Characterizing High-Frequency Devices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

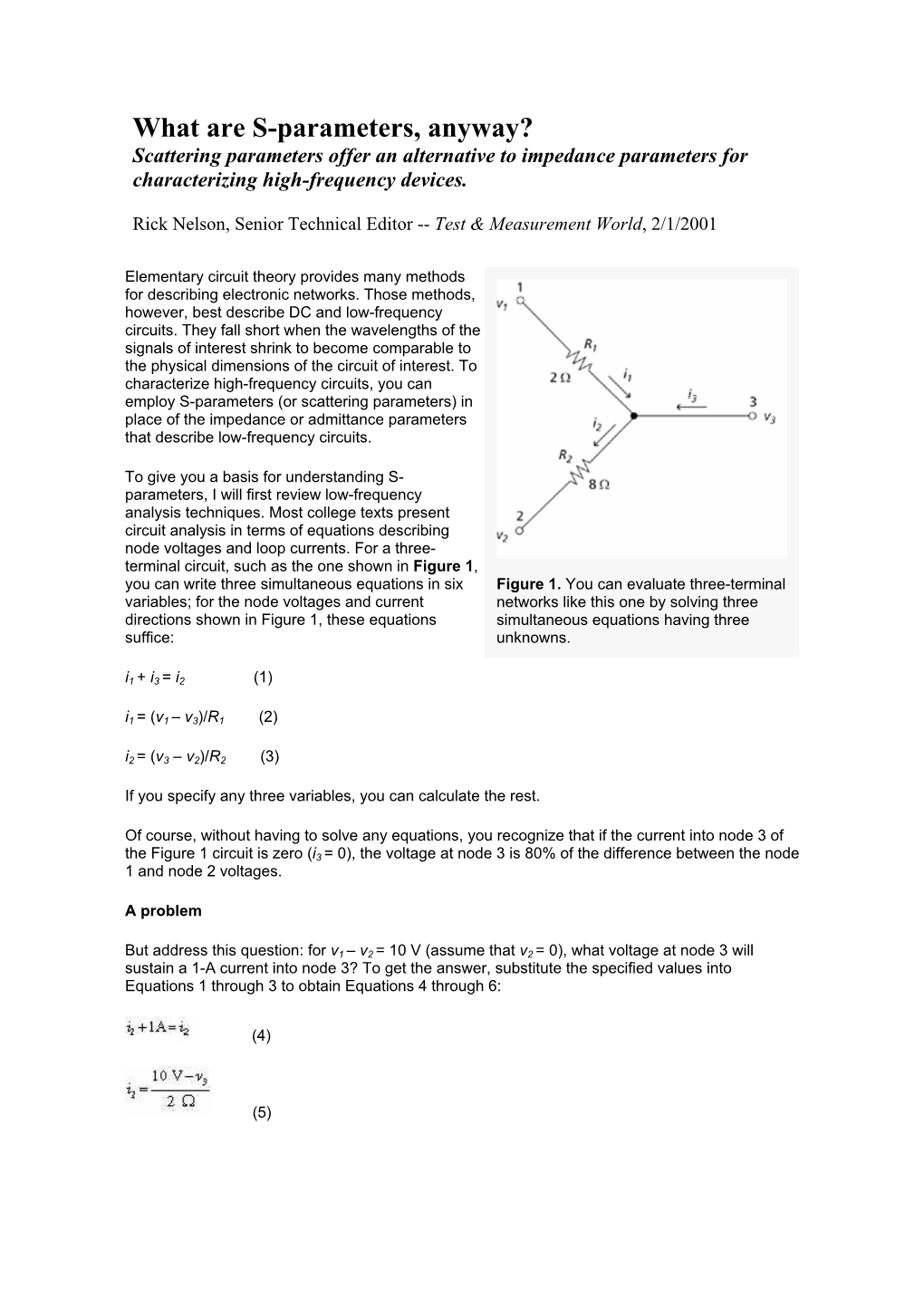

Recommended publications

-

Scattering Parameters

Scattering Parameters Motivation § Difficult to implement open and short circuit conditions in high frequencies measurements due to parasitic L’s and C’s § Potential stability problems for active devices when measured in non-operating conditions § Difficult to measure V and I at microwave frequencies § Direct measurement of amplitudes/ power and phases of incident and reflected traveling waves 1 Prof. Andreas Weisshaar ― ECE580 Network Theory - Guest Lecture ― Fall Term 2011 Scattering Parameters Motivation § Difficult to implement open and short circuit conditions in high frequencies measurements due to parasitic L’s and C’s § Potential stability problems for active devices when measured in non-operating conditions § Difficult to measure V and I at microwave frequencies § Direct measurement of amplitudes/ power and phases of incident and reflected traveling waves 2 Prof. Andreas Weisshaar ― ECE580 Network Theory - Guest Lecture ― Fall Term 2011 1 General Network Formulation V + I + 1 1 Z Port Voltages and Currents 0,1 I − − + − + − 1 V I V = V +V I = I + I 1 1 k k k k k k V1 port 1 + + V2 I2 I2 V2 Z + N-port 0,2 – port 2 Network − − V2 I2 + VN – I Characteristic (Port) Impedances port N N + − + + VN I N Vk Vk Z0,k = = − + − Z0,N Ik Ik − − VN I N Note: all current components are defined positive with direction into the positive terminal at each port 3 Prof. Andreas Weisshaar ― ECE580 Network Theory - Guest Lecture ― Fall Term 2011 Impedance Matrix I1 ⎡V1 ⎤ ⎡ Z11 Z12 Z1N ⎤ ⎡ I1 ⎤ + V1 Port 1 ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ - V2 Z21 Z22 Z2N I2 ⎢ ⎥ = ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ I2 + ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ V2 Port 2 ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ ⎢ ⎥ - V Z Z Z I N-port ⎣ N ⎦ ⎣ N1 N 2 NN ⎦ ⎣ N ⎦ Network I N [V]= [Z][I] V + Port N N + - V Port i i,oc- Open-Circuit Impedance Parameters Port j Ij N-port Vi,oc Zij = Network I j Port N Ik =0 for k≠ j 4 Prof. -

Brief Study of Two Port Network and Its Parameters

© 2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 6 | ISSN : 2349-6002 Brief study of two port network and its parameters Rishabh Verma, Satya Prakash, Sneha Nivedita Abstract- this paper proposes the study of the various ports (of a two port network. in this case) types of parameters of two port network and different respectively. type of interconnections of two port networks. This The Z-parameter matrix for the two-port network is paper explains the parameters that are Z-, Y-, T-, T’-, probably the most common. In this case the h- and g-parameters and different types of relationship between the port currents, port voltages interconnections of two port networks. We will also discuss about their applications. and the Z-parameter matrix is given by: Index Terms- two port network, parameters, interconnections. where I. INTRODUCTION A two-port network (a kind of four-terminal network or quadripole) is an electrical network (circuit) or device with two pairs of terminals to connect to external circuits. Two For the general case of an N-port network, terminals constitute a port if the currents applied to them satisfy the essential requirement known as the port condition: the electric current entering one terminal must equal the current emerging from the The input impedance of a two-port network is given other terminal on the same port. The ports constitute by: interfaces where the network connects to other networks, the points where signals are applied or outputs are taken. In a two-port network, often port 1 where ZL is the impedance of the load connected to is considered the input port and port 2 is considered port two. -

Solutions to Problems

Solutions to Problems Chapter l 2.6 1.1 (a)M-IC3T3/2;(b)M-IL-3y4J2; (c)ML2 r 2r 1 1.3 (a) 102.5 W; (b) 11.8 V; (c) 5900 W; (d) 6000 w 1.4 Two in series connected in parallel with two others. The combination connected in series with the fifth 1.5 6 V; 16 W 1.6 2 A; 32 W; 8 V 1.7 ~ D.;!b n 1.8 in;~ n 1.9 67.5 A, 82.5 A; No.1, 237.3 V; No.2, 236.15 V; No. 3, 235.4 V; No. 4, 235.65 V; No.5, 236.7 V Chapter 2 2.1 3il + 2i2 = 0; Constraint equation, 15vl - 6v2- 5v3- 4v4 = 0 i 1 - i2 = 5; i 1 = 2 A; i2 = - 3 A -6v1 + l6v2- v3- 2v4 = 0 2.2 va\+va!=-5;va=2i2;va=-3il; -5vl- v2 + 17v3- 3v4 = 0 -4vl - 2vz- 3v3 + l8v4 = 0 i1 = 2 A;i2 = -3 A 2.7 (a) 1 V ±and 2.4 .!?.; (b) 10 V +and 2.3 v13 + v2 2 = 0 (from supernode 1 + 2); 10 n; (c) 12 V ±and 4 n constraint equation v1- v2 = 5; v1 = 2 V; v2=-3V 2.8 3470 w 2.5 2.9 384 000 w 2.10 (a) 1 .!?., lSi W; (b) Ra = 0 (negative values of Ra not considered), 162 W 2.11 (a) 8 .!?.; (b),~ W; (c) 4 .!1. 2.12 ! n. By the principle of superposition if 1 A is fed into any junction and taken out at infinity then the currents in the four branches adjacent to the junction must, by symmetry, be i A. -

2-PORT CIRCUITS Objectives

Notes for course EE1.1 Circuit Analysis 2004-05 TOPIC 10 – 2-PORT CIRCUITS Objectives: . Introduction . Re-examination of 1-port sub-circuits . Admittance parameters for 2-port circuits . Gain and port impedance from 2-port admittance parameters . Impedance parameters for 2-port circuits . Hybrid parameters for 2-port circuits 1 INTRODUCTION Amplifier circuits are found in a large number of appliances, including radios, TV, video, audio, telephony (mobile and fixed), communications and instrumentation. The applications of amplifiers are practically unlimited. It is clear that an amplifier circuit has an input signal and an output signal. This configuration is represented by a device called a 2-port circuit, which has an input port for the input signal and an output port for the output signal. In this topic, we look at circuits from this point of view. To develop the idea of 2-port circuits, consider a general 1-port sub-circuit of the type we are very familiar with: The basic passive elements, resistor, inductor and capacitor, and the independent sources, are the simplest 1-port sub-circuits. A more general 1-port sub-circuit contains any number of interconnected resistors, capacitors, inductors, and sources and could have many nodes. Sometimes, perhaps when we have finished designing a circuit, we become less interested in the detail of the elements interconnected in the circuit and are happy to represent the 1-port circuit by how it behaves at its terminals. This is achieved by use of circuit analysis to determine the relationship between the voltage V1 across the terminals and the current I1 flowing through the terminals which leads to a Thevenin or Norton equivalent circuit, which can be used as a simpler replacement for the original complex circuit. -

Two-Port Circuits

Berkeley Two-Port Circuits Prof. Ali M. Niknejad U.C. Berkeley Copyright c 2016 by Ali M. Niknejad February 12, 2016 1 / 32 A Generic Amplifier YS + y y v 11 12 s y y YL 21 22 − Consider the generic two-port (e.g. amplifier or filter) shown above. A port is defined as a terminal pair where the current entering one terminal is equal and opposite to the current exiting the second termianl. Any circuit with four terminals can be analyzed as a two-port if it is free of independent sources and the current condition is met at each terminal pair. All the complexity of the two-port is captured by four complex numbers (which are in general frequency dependent). 2 / 32 Two-Port Parameters There are many two-port parameter set, which are all equivalent in their description of the two-port, including the admittance parameters (Y ), impedance parameters (Z), hybrid or inverse-hybrid parameters (H or G), ABCD, scattering S, or transmission (T ). Y and Z paramters relate the port currents (voltages) to the port voltages (currents) through a 2x2 matrix. For example v z z i i y y v 1 = 11 12 1 1 = 11 12 1 v2 z21 z22 i2 i2 y21 y22 v2 Hybrid parameters choose a combination of v and i. For example hybrid H and inverse hybrid G (dual) v1 h11 h12 i1 = i1 g11 g12 v1 i2 h21 h22 v2 = v2 g21 g22 i2 3 / 32 Scattering Parameters Even if we didn't know anything about incident and reflected waves, we could define scattering parameters in the following way. -

S-Parameters

664 14. S-Parameters b1 S11 S12 a1 S11 S12 14 = ,S= (scattering matrix) (14.1.3) b2 S21 S22 a2 S21 S22 S-Parameters The matrix elements S11,S12,S21,S22 are referred to as the scattering parameters or the S-parameters. The parameters S11, S22 have the meaning of reflection coefficients, and S21, S12, the meaning of transmission coefficients. The many properties and uses of the S-parameters in applications are discussed in [1135–1174]. One particularly nice overview is the HP application note AN-95-1 by Anderson [1150] and is available on the web [1847]. We have already seen several examples of transfer, impedance, and scattering ma- trices. Eq. (11.7.6) or (11.7.7) is an example of a transfer matrix and (11.8.1) is the corresponding impedance matrix. The transfer and scattering matrices of multilayer structures, Eqs. (6.6.23) and (6.6.37), are more complicated examples. 14.1 Scattering Parameters The traveling wave variables a1,b1 at port 1 and a2,b2 at port 2 are defined in terms of V1,I1 and V2,I2 and a real-valued positive reference impedance Z0 as follows: Linear two-port (and multi-port) networks are characterized by a number of equivalent + − circuit parameters, such as their transfer matrix, impedance matrix, admittance matrix, V1 Z0I1 V2 Z0I2 a1 = a2 = and scattering matrix. Fig. 14.1.1 shows a typical two-port network. 2 Z0 2 Z0 (traveling waves) (14.1.4) − + V1 Z0I1 V2 Z0I2 b1 = b2 = 2 Z0 2 Z0 The definitions at port 2 appear different from those at port 1, but they are really the same if expressed in terms of the incoming current −I2: − + − V2 Z0I2 V2 Z0( I2) a2 = = Fig. -

Chapter 7 Two-Port Network

Chapter 7 Two-port network 7.1 Impedance parameters definition, examples 7.2 Admittance parameters definition, examples 7.3 Hybrid parameters definition, examples 7.4 Transmission parameters definition, examples 7.5 Conversion of the impedance, admittance, chain, and hybrid parameters 7.6 Scattering parameters definition, characteristics, examples 7.7 Conversion from impedance, admittance, chain, and hybrid parameters to scattering parameters or vice versa 7.8 Chain scattering parameters 7-1 微波工程講義 7.1 Impedance parameters I1 I2 Basics linear 1. V1 port 1 port 2 V2 network [V ]= [Z ][][]I , I : source, [V ]: response V Z Z I V = Z I + Z I reference reference 1 = 11 12 1 , 1 11 1 12 2 = + plane 1 plane 2 V2 Z 21 Z 22 I 2 V2 Z 21I1 Z 22 I 2 V = 1 Z11 : open - circuit input impedance at port 1 I1 = I2 0 V = 1 Z12 : open - circuit reverse transimpedance I 2 = I1 0 V = 2 Z 21 : open - circuit forward transimpedance I1 = I2 0 V = 2 Z 22 : open - circuit input impedance at port 2 I 2 = I1 0 7-2 微波工程講義 Lecture 4 How to Determine Z Parameters? =⋅+⋅ I = 0 VZIZI11111222 ==VV12 ZZ11 21 =⋅+⋅ II11== VZIZI2211222 II2200 = I1 0 ==VV21 ZZ22 12 II22== II1100 I1=0 I2 Z22 Two Port Reciprocity: O.C. V1 V Network 2 = Z12Z 21 1/9/2003 2 Lecture 4. ELG4105: Microwave Circuits © S. Loyka, Winter 2003 Discussion I1 I2 V 6I = = Ω = 1 = 2 = 1. Ex.7.1 Z11 Z 22 6 , Z12 6 I 2 = I 2 I1 0 6Ω V 6I 6 6 V1 V2 Z = 2 = 1 = 6,[]Z = 21 1 6 6 I1 I =0 I1 2. -

Coupling Coefficient Measurement Method with Simple Procedures

energies Article Coupling Coefficient Measurement Method with Simple Procedures Using a Two-Port Network Analyzer for a Multi-Coil WPT System Seon-Jae Jeon and Dong-Wook Seo * Department of Radio Communication Engineering, Korea Maritime and Ocean University (KMOU), 727 Taejong-ro, Yeongdo-gu, Busan 49112, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-51-410-4427 Received: 10 September 2019; Accepted: 16 October 2019; Published: 17 October 2019 Abstract: In this paper, we propose a measurement method with a simple procedure based on the definition of the impedance parameter using a two-port network analyzer. The main advantage of the proposed measurement method is that there is no limit on the number of measuring coils, and the method has a simple measurement procedure. To verify the proposed method, we measured the coupling coefficient among three coils with respect to the distance between the two farthest coils at 6.78 and 13.56 MHz, which are frequencies most common for a wireless power transfer (WPT) system in high-frequency band. As a result, the proposed method showed good agreement with results of the conventional S-parameter measurement methods. Keywords: coupling coefficient; impedance matrix; multiple coils; mutual inductance; scattering matrix; transfer impedance; wireless power transfer 1. Introduction The conventional wireless power transfer (WPT) system with two coils has obvious limits; the system is very sensitive to the transmission distance and alignment between the coils [1,2]. To resolve these problems, adaptive or tunable matching networks have been adopted [3,4], and a transmitting module not with a single coil, but with multiple coils has been also introduced into the WPT system [5,6]. -

S-Parameter Simulation

Advanced Design System 2011.01 - S-Parameter Simulation Advanced Design System 2011.01 Feburary 2011 S-Parameter Simulation 1 Advanced Design System 2011.01 - S-Parameter Simulation © Agilent Technologies, Inc. 2000-2011 5301 Stevens Creek Blvd., Santa Clara, CA 95052 USA No part of this documentation may be reproduced in any form or by any means (including electronic storage and retrieval or translation into a foreign language) without prior agreement and written consent from Agilent Technologies, Inc. as governed by United States and international copyright laws. Acknowledgments Mentor Graphics is a trademark of Mentor Graphics Corporation in the U.S. and other countries. Mentor products and processes are registered trademarks of Mentor Graphics Corporation. * Calibre is a trademark of Mentor Graphics Corporation in the US and other countries. "Microsoft®, Windows®, MS Windows®, Windows NT®, Windows 2000® and Windows Internet Explorer® are U.S. registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Pentium® is a U.S. registered trademark of Intel Corporation. PostScript® and Acrobat® are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. UNIX® is a registered trademark of the Open Group. Oracle and Java and registered trademarks of Oracle and/or its affiliates. Other names may be trademarks of their respective owners. SystemC® is a registered trademark of Open SystemC Initiative, Inc. in the United States and other countries and is used with permission. MATLAB® is a U.S. registered trademark of The Math Works, Inc.. HiSIM2 source code, and all copyrights, trade secrets or other intellectual property rights in and to the source code in its entirety, is owned by Hiroshima University and STARC. -

Two-Port Networks (I&N Chap 16.1-6)

Two-Port Networks (I&N Chap 16.1-6) • Introduction • Impedance/Admittance Parameters • Hybrid Parameters • Transmission Parameters • Interconnecting Two-Port Networks Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.1 Single-Port Circuit A “port” refers to a pair of terminals through which a single current flows and across which there is a single voltage. Externally, either voltage or current could be independently specified while the other quantity would be computed. The Thevenin equivalent permits a simple model of the linear network, regardless of the number of components in the network. Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.2 Two-Port A two-port network requires two terminal pairs (total 4 terminals). Amongst the two voltages and two currents shown, generally two can be independently specified (externally). How many distinct pairs of independent quantities are possible? By convention, regard Port 1 as the input and Port 2 as the input (and use the polarity labels shown). We consider circuits with no internal independent sources. Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.3 Motivating Examples We’ve seen two-ports before. Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.4 Admittance Parameters = Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.5 Impedance Parameters = Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.6 Example Find the two-port admittance and impedance parameters. Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.7 Hybrid Parameters = E.g. Consider the ideal Xformer. Do the admittance or impedance parameters exist? Based on slides by J. Yan Slide 4.8 Transistor Hybrid Parameters The “small signal” analysis (DC analysis of quiescent point is separate) of BJTs often utilises hybrid parameters. -

Network Scatter^G Parameters

MiLUJ,u4.iJ.in>ifCTi;mkffl.iJ.!,.i.iiM»i ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■iMaiiHMBBKiiiMiH ■■■■■ NETWORK SCATTER^G PARAMETERS R Mav^ddatj World Scientific NETWORK SCATTERING PARAMETERS R Mavaddat University of Western Australia ADVANCED SERIES IN CIRCUITS AND SYSTEMS Editor-in-Charge: Wai-Kai Chen (Univ. Illinois, Chicago, USA) Associate Editor: Dieter A. MIynski (Univ. Karlsruhe, Germany) Published Vol. 1: Interval Methods for Circuit Analysis by L. V. Kolev Advanced Series in Circuits and Systems - Vol. 2 NETWORK SCATTERING PARAMETERS R Mavaddat University of Western Australia World Scientific Singapore • New Jersey * London • Hong Kong Published by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. P O Box 128, Farrer Road, Singapore 912805 USA office: Suite IB, 1060 Main Street, River Edge, NJ 07661 UK office: 57 Shelton Street, Covent Garden, London WC2H 9HE NETWORK SCATTERING PARAMETERS Copyright © 1996 by World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd. All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without written permission from the Publisher. For photocopying of material in this volume, please pay a copying fee through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, Massachusetts 01923, USA. ISBN 981-02-2305-6 Printed in Singapore. Contents Preface vii 1. Introduction and The Scattering Parameters of a 1-port Network 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Scattering Parameters of a 1 -port Network 6 1.3 The Wave Amplitudes of a General 1 -port Network - Signal Flow graphs 10 1.4 1-Port Network Input Impedance and Network Stability 14 1.5 Power Considerations 18 1.6 The Generalized Scattering Parameters 21 2. -

Two-Port Networks

Two-Port Networks 16.1 TWO-PORT NETWORK Generally any network may be represented schematically by a rectangular box. A network may be used for representing either source or load, or for a variety of purposes. A pair of terminals at which a signal may enter or leave a network is called a port. A port is defined as any pair of terminals into which energy is supplied, or from which energy is withdrawn, or where the network variables may be measured. One such network having only one pair of terminals (1-19) is shown in Fig. 16.1 (a). A two-port network is simply a network inside a black box, and the network has only CHAPTER 16 two pairs of accessible terminals; usually one pair represents the input and the other Fig. 16.1 represents the output. Such a building block is very common in electronic systems, communication systems, transmission and distribution systems. Figure 16.1(b) shows a two-port network, or two terminal pair network, in which the four terminals have been paired into ports 1-19 and 2-29. The terminals 1-19 together constitute a port. Similarly, the terminals 2-29 constitute another port. Two ports containing no sources in their branches are called passive ports; among them are power transmission lines and transformers. Two ports containing sources in their branches are called active ports. A voltage and current assigned to each of the two ports. The voltage and current at the input terminals are V1 and I1; whereas V2 and I2 are specified at the output port.