View/Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maranoa Mail

David Littleproud MP View this email in your browser A New Year I hope you had a wonderful Christmas with family and friends and you were able to relax with some New Year cheer! A new year means new beginnings and the parliamentary sittings are set to resume in a few weeks’ time. I’ll continue to work hard and be your voice in Federal Parliament and this Coalition Government has real plans to make our nation stronger and to better support you, your family, business and community. What it means to be Australian In the lead-up to Australia Day this week, I’ve found myself contemplating what it means to be Australian. Australian citizenship should be cherished and entering, or remaining, in Australia is a privilege. 1 We need to strengthen citizenship laws so they better align with Australian values. That’s why I strongly support a tougher citizenship test that would strengthen character requirements for any new potential Australian following concerns that Australia’s short-term visa pathways could be exploited by terrorists seeking access to our country. Immigration Minister Peter Dutton has also flagged other reforms for consideration, including dropping the age at which good character provisions apply for citizenship from 18 to 16 years. If young people are breaking the law, I don’t think they deserve to part of our society. At the end of the day, we have secure borders that are envied by most European countries because of this government’s strong stance on border protection. These reforms are really about making sure Australia remains safe and I strongly support any move by this government to make our citizenship rules more robust a priority when we head back to Canberra next month. -

Traffic Management Scheme

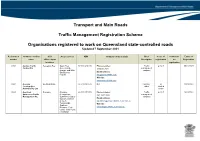

Transport and Main Roads Traffic Management Registration Scheme Organisations registered to work on Queensland state-controlled roads Updated 7 September 2021 Registration Company / trading QLD Areas services ABN Company contact details Brief Scope of Conditions Expiry of number name office / depot Description registration on Registration locations registration 0202 Aaction Traffic Deception Bay South East 37 128 649 445 Phone number: Traffic O, S, D 30/11/2023 Control P/L Queensland, 1300 055 619 management Gympie and Wide company Bay Burnett Email address: regions [email protected] Website: www.aactiontraffic.com 0341 Acciona South Brisbane 66 618 030 872 N/A Industry - D 31/01/2023 Construction other Limited Australia Pty Ltd scope 0043 Acquired Brendale Brisbane 45 831 570 559 Phone number: Traffic O, S, D 15/12/2022 Awareness Traffic Metropolitan, (07) 3881 3008 management Management P/L Sunshine Coast to company Gympie, western Email address: areas to [email protected] Toowoomba, Website: Southern Brisbane, Gold www.acquiredawareness.com.au Coast, Gold Coast Hinterland Registration Company / trading QLD Areas services ABN Company contact details Brief Scope of Conditions Expiry of number name office / depot Description registration on Registration locations registration 0278 Action Control Labrador South East 92 098 736 899 Phone Number: Traffic O, S 31/10/2021 (Aust) P/L Queensland 0403 320 558 management Limited company scope Email address: [email protected] Website: www.actioncontrol.com.au 0271 -

Council Meeting Notice & Agenda 15

COUNCIL MEETING NOTICE & AGENDA 15 December 2020 49 Stockyard Street Cunnamulla Qld 4490 www.paroo.qld.gov.au Agenda General Meeting of Council Notice is hereby given that the Ordinary Meeting of Council is to be held on Tuesday, 15th December 2020 at the Cunnamulla Shire Hall, Jane Street Cunnamulla, commencing at 9.00am 1 OPENING OF MEETING 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF TRADITIONAL OWNERS 3 ATTENDANCES AND APOLOGIES 4 MOTION OF SYMPATHY • Mr Peter Doyle • Ms Grace Brown • Pat Cooney 5 CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Recommendation: That Council adopt the minutes of the General Meeting of Council held Tuesday, 17th November 2020 as a true and correct record of that meeting. 6 DECLARATION OF INTEREST BEING 6.1 Material Personal Interest 6.2 Conflict Of Interest 7 MAYOR 1 7.1 Mayor’s Report 8 OFFICER REPORTS 8.1 DIRECTOR INFRASTRUCTURE 8.1.1 Operations Report 3 8.1.2 Rubbish Truck Replacement Report 12 8.2 DIRECTOR COMMUNITY SUPPORT AND ENGAGEMENT 8.2.1 Community Services Report 15 8.2.2 Library Services Report 20 8.2.3 Tourism Report 23 8.2.4 Local Laws Report 29 8.2.5 Rural Lands and Compliance Report 32 8.2.6 Community Support – Strides Blue Tree 34 10.30 First 5 Forever Video Competition Winners announced – Winners to attend to receive awards Morning Tea 8.3 CHIEF FINANCE OFFICER 8.3.1 Finance Report 36 8.4 CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 8.4.1 Action Item Register 52 8.4.2 Office of the Chief Executive Officer’s Report 57 8.4.3 Grants Report 63 8.4.4 Project Management Report 66 8.4.5 Policy Report 69 9 LATE REPORTS 10 CLOSED SESSION - CONFIDENTIAL 11 CORRESPONDENCE 11.1 Special Gazetted Public Holiday 132 11.2 2021 QOGM Paroo 141 11.3 MDA Change of Name Consultation 143 12 CLOSURE OF MEETING 155 Ms Cassie White Chief Executive Officer 09th December 2020 General Council Meeting Notice & Agenda 15 December 2020 7.1 Mayor’s Report Council Meeting: 15 December 2020 Department: Office of the Mayor Author: Suzette Beresford, Mayor Purpose The purpose of this report is to provide an update on the meetings and teleconferences that Mayor Beresford has attended. -

Longreach Info

Nice to know!!! Some interesting information about Longreach and what you can do here. The Longreach Region, Capital of the Outback, incorporates the vibrant towns of Ilfracombe, Isisford, Yaraka and Longreach, each offering unique attractions: The traditional owners of the land are the Iningai people, accord- ing to records there are no known Iningai people in existence to- day. The Iningai people lived along the Thomson River from near Stonehenge to Muttaburra prior to European occupation. Innin- gai Park is a nature reserve that is part of the Longreach Town Common and includes sections of floodplain and waterholes along Gin Creek. Unfortunately, there are no recognized Iningai tradi- tional owners remaining. Several Indigenous families from the Barcaldine and Longreach areas are now the historical custodians of what is left of the Iningai culture; these people are the custodi- ans of the Iningai Keeping Place. Visit world class attractions in Longreach, Qantas Founders Mu- seum, Powerhouse Museum and the Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame. Take a Cobb ‘n’ Co ride thru the scrub or a cruise on the Thomson River. Discover Ilfracombe, renowned throughout Australia for its pre- served history, the ‘Great Machinery Mile”, Langenbaker House, and the Historic Wellshot Hotel and Centre. Yaraka, offers an historical railway museum, with Mount Slowcombe a short distance away providing breathtaking views. Emmet has an interesting historical display and revamped railway Experience Isisford, home to “Isisfordia duncani” a pre-historic crocodile fossil housed in the Outer Barcoo Interpretive Centre, camp or fish along the Barcoo or stroll along St Mary’s Street and discover the many examples of pioneering heritage architecture. -

SPER Hardship Partner Application Form

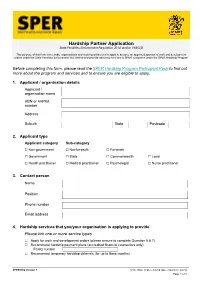

Hardship Partner Application State Penalties Enforcement Regulation 2014 section 19AG(2) This purpose of this form is to enable organisations and health practitioners to apply to become an approved sponsor of work and development orders under the State Penalties Enforcement Act 1999 and/or provide advocacy services to SPER customers under the SPER Hardship Program Before completing this form, please read the SPER Hardship Program Participant Pack to find out more about the program and services and to ensure you are eligible to apply. 1. Applicant / organisation details Applicant / organisation name ABN or AHPRA number Address Suburb State Postcode 2. Applicant type Applicant category Sub-category ☐ Non-government ☐ Not-for-profit ☐ For-profit ☐ Government ☐ State ☐ Commonwealth ☐ Local ☐ Health practitioner ☐ Medical practitioner ☐ Psychologist ☐ Nurse practitioner 3. Contact person Name Position Phone number Email address 4. Hardship services that you/your organisation is applying to provide Please tick one or more service types ☐ Apply for work and development orders (please ensure to complete Question 6 & 7) ☐ Recommend hardship payment plans (accredited financial counsellors only) FCAQ number ☐ Recommend temporary hardship deferrals (for up to three months) SPER6002 Version 1 ©The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) Page 1 of 8 5. Locations where you/your organisation will provide these services ☐ All of Queensland or Select Local Government Area(s) below: ☐ Aurukun Shire ☐ Fraser Coast Region ☐ North Burnett Region ☐ Balonne -

Outback Regional Tourism Workforce Plan 2018-2020

June 2018 Outback Regional Tourism Workforce Plan 2018–2020 Front cover photo: Tree of Knowledge, Barcaldine. Photographer: Paul Ewart. Photo courtesy of Tourism & Events Queensland. Copyright This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. Licence This work is licensed by Jobs Queensland under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 3.o Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit: http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ You are free to copy, communicate and adapt this publication, as long as you attribute it as follows: © State of Queensland, Jobs Queensland, June 2018. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Services (TIS National) on telephone 131 450 and ask them to contact Jobs Queensland on (07) 3436 6190. Disclaimer While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a results of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Introduction Tourism is a $25.4 billion industry in Queensland, providing direct and indirect employment for approximately 217,000 people or 9.1 per cent of the State’s workforce.1 Tourism encompasses multiple sectors because visitors consume goods and services sourced across the economy.2 The industry includes: transport (air, rail, road and water); accommodation; attractions; events; food services (takeaway, cafés and restaurants); clubs and casinos; retail; arts and recreation; travel agencies and tour operators; education and training; and tourism (marketing, information and planning). -

Tourism Development Plan

Flinders Shire Council Explore Create Engage March 2018 Content produced by Tourism Tribe contents 1.0 Executive Summary 4 2.0 Introduction 6 3.0 Situation Analysis 7 4.0 Competitor Analysis 16 5.0 Stakeholder Feedback 22 6.0 SWOT Analysis 24 7.0 Strategic Opportunities and Action Plan 26 8.0 Appendix 32 1.0 Executive Summary 1.1 Overview 1.2 Major Attractions for Visitors The Flinders Shire is situated 383kms southwest The Flinders Shire is fortunate to have the stand- of Townsville, and is made up of the townships out iconic natural attraction that is Porcupine of Hughenden, Prairie, Torrens Creek and Gorge National Park, only 64kms (40 minutes Stamford. Hughenden is the major town centre drive) from the major town centre, Hughenden, in the Shire and is featured on a number of with sealed road access. This pristine national Outback drives and on Australia’s Dinosaur park attraction sets the Flinders Shire apart from Trail. The majority of visitors arrive on their way surrounding Council areas in the North West east towards Charters Towers and Townsville, precinct of the Queensland Outback. and some stay for the day or one night on their travels west. Whilst enhanced marketing strategies could generate increased visitation to the Gorge, it is There are four national parks within the Flinders highly unlikely that the surrounding experiences Shire, with Porcupine Gorge being the unique and products would adequately service the natural asset that is often cited as the main consumer to keep them in the area beyond reason for visiting the shire. -

PLC Exchange Cycle 3 2021

Public Library Collections 2021 Exchange Calendar – Cycle 3 (Selection Week) Week Dates Council/Region Library Branch Exchange Total number 1 16-20 Aug Cloncurry Shire Cloncurry Bob McDonald Library 419 Weipa Town Hibberd Library 496 Charters Towers Region Charters Towers 596 1,511 2 23-27 Aug Etheridge Shire Georgetown Library 232 Torres Shire Torres Shire Library 458 Southern IKC Cherbourg IKC 267 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Kubin IKC 270 (2 Exchanges per year) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Warraber IKC 270 (2 Exchanges per year) 1,497 3 30 Aug-3 Sep Burke Shire Burketown Library 167 Richmond Shire Richmond Library 237 Eastern Cape IKC Yarrabah IKC 334 Eastern Cape IKC Hope Vale IKC 334 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Boigu IKC 270 (2 Exchanges per year) 1,342 4 6-10 Sep Barcoo Shire Jundah Public Library 94 Barcoo Shire Stonehenge Library 79 Barcoo Shire Windorah Library 78 Carpentaria Shire Karumba Library 184 Carpentaria Shire Normanton Library 182 * Torres Strait Island Regional Council Mabuiag IKC 270 (2 Exchanges per year) (to be despatched 20-24 Sep) * Torres Strait Island Regional Council Iama IKC 270 (2 Exchanges per year) (to be despatched 20-24 Sep) Western Cape IKC Napranum IKC 267 1,424 5 13-17 Sep Maranoa Region Injune Library 102 Maranoa Region Jackson Library 91 Maranoa Region Mitchell Library 128 Maranoa Region Mungallala Library 85 Maranoa Region Roma Library 707 Maranoa Region Surat Library 71 Maranoa Region Wallumbilla Library 73 Maranoa Region Yuleba Library 54 Eastern Cape IKC Wujal Wujal -

General Council Meeting

General Council Meeting Notice is hereby given pursuant to the provisions of the Local Government Regulation 2012, that the next Meeting of the Central Highlands Regional Council will be held in the Council Chambers, 65 Egerton Street, Emerald on Tuesday, 14 May 2019 At 2.30 pm For the purpose of considering the items included on the Agenda. Scott Mason Chief Executive Officer OUR VISION A progressive region creating opportunities for all OUR MISSION We are a council committed to continuous improvement, a sustainable future and efficient investment in our communities OUR VALUES Respect and Integrity Accountability and Transparency Providing Value Commitment and Teamwork OUR PRIORITIES COUNCIL AGENDA Strong, vibrant communities Building and maintaining quality infrastructure Supporting our local economy Protecting our people and our environment Leadership and governance Our organisation Agenda - General Council Meeting - 14 May 2019 AGENDA CONTENTS 1 PRESENT ..................................................................................................................................................4 2 APOLOGIES..............................................................................................................................................4 3 LEAVE OF ABSENCE...............................................................................................................................4 4 OPENING PRAYER...................................................................................................................................4 -

Central West Queensland National Parks Journey Guide

Queensland National Parks Central West Queensland National Parks Contents Welcome to Central West Queensland national parks Parks at a glance (facilities and activities) ..................................2 Welcome .....................................................................................3 Be adventurous! Map of Central West Queensland ................................................4 Journey Choose your escape ....................................................................5 off the beaten track over dusty Savour roads or desert dunes into Experience the Outback ..............................................................6 sunlit plains extended, wildflowers Queensland’s dry, but far from lifeless, heart. Discover a land of boom and bust ...............................................8 blossoming after rain and the freedom of sleeping out under a blanket of A Idalia National Park ...................................................................10 never-ending stars. Welford National Park ...............................................................12 Follow Lochern National Park ...............................................................14 the footsteps of superbly adapted arid-zone creatures and long-departed Forest Den National Park ...........................................................15 dinosaurs. Traverse ancient Aboriginal Bladensburg National Park ........................................................16 trading routes and the tracks of hardy explorers and resilient stockmen. Combo Waterhole Conservation -

Pest Management Plan for the Longreach Region

Longreach Regional Council PEST MANAGEMENT PLAN 2010 to 2014 Photos used are from QPIF and NRW Pest Management Plan for Longreach Regional Council Longreach Regional Council Pest Management Plan Table of contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3 1.1 Purpose 3 1.2 Background 3 1.3 Scope of a Pest Management Plan 1.4 Working Group 3 1.5 Goals of Pest Management Plan 3 1.6 Mission Statement 4 1.7 Key Objectives 4 1.8 Reviewing the Plan 5 2.0 Stakeholders Responsibilities 6 Table 1: Classes of declared pests under the Act 6 3.0 Declared and other locally significant weeds and pest animals 7 3.1 Pest Animals 8 Weeds 8 3.2 Longreach Regional Council Policies 8 3.3 Standard Operating Procedures 8 Wild dogs (Canis familiaris) 11 Feral pigs (Sus scrofa) 13 Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) 14 Feral cats (Felis catus) 15 Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) 16 Locusts 17 Prickly acacia (Acacia nilotica) 18 Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) 18 Parkinsonia (Parkinsonia aculeate) 18 Parthenium (Parthenium hysterophorous) 20 Rubber vine (Cryptostegia grandiflora) 22 Bellyache Bush (Jatropha gossypifolia) 23 Mother of Millions (Bryophyllum delagoense) 25 Cactus (Cylindropuntia species) 25 Florestina (Florestina tripteris) 26 Leucaena (Leucaena leucocephala) 27 4.0 Strategies used in the Pest Management Plan 28 Pest Management Plan for Longreach Regional Council Page 3 of 43 Executive Summary The Longreach Regional Council Pest Management Plan (PMP) was developed for the benefit of the whole community and is prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Land Protection (Pest and Stock Route Management) Act 2002 Queensland. With the implementation of the Land Protection (Pest and Stock Route Management) Act 2002 very clear responsibilities are identified for local government and land owners. -

Public Library Collections 2021 Exchange Calendar – Cycle 2 (Selection Week)

Public Library Collections 2021 Exchange Calendar – Cycle 2 (Selection Week) Week Dates Council/Region Library Branch Exchange number Total 1 26 Apr-30 May Cloncurry Shire Cloncurry Bob McDonald Library 419 Weipa Town Hibberd Library 496 Charters Towers Region Charters Towers 596 1,511 2 3-7 May Etheridge Shire Georgetown Library 232 Torres Shire Torres Shire Library 458 Southern IKC Cherbourg IKC 267 957 3 10-14 May Burke Shire Burketown Library 167 Richmond Shire Richmond Library 237 Eastern Cape IKC Yarrabah IKC 334 Eastern Cape IKC Hope Vale IKC 334 1,072 4 17-21 May Barcoo Shire Jundah Public Library 94 Barcoo Shire Stonehenge Library 79 Barcoo Shire Windorah Library 78 Carpentaria Shire Karumba Library 184 Carpentaria Shire Normanton Library 182 Western Cape IKC Napranum IKC 267 884 5 24-28 May Maranoa Region Injune Library 102 Maranoa Region Jackson Library 91 Maranoa Region Mitchell Library 128 Maranoa Region Mungallala Library 85 Maranoa Region Roma Library 707 Maranoa Region Surat Library 71 Maranoa Region Wallumbilla Library 73 Maranoa Region Yuleba Library 54 Eastern Cape IKC Wujal Wujal IKC 267 1,578 6 31 May-4 Jun Cook Shire Bloomfield Library 128 Cook Shire Cooktown Library 504 Blackall-Tambo Region Blackall Library 261 Blackall-Tambo Region Tambo Library 102 995 7 7-11 Jun North Burnett Region Biggenden Library 101 North Burnett Region Eidsvold Library 117 North Burnett Region Gayndah Library 168 North Burnett Region Monto Library 167 North Burnett Region Mundubbera Library 196 North Burnett Region Perry Library 102 Southern