An Gleann's Robh Mi Og

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultation of Proposals for Overprovision Statement 2013-16

The Highland Licensing Board Agenda 4 Item Meeting – 27 August 2013 Report HLB/107/13 No Consultation on Proposals for Overprovision Statement 2013-16 Report by the Clerk to the Board Summary Following receipt of the evidence and recommendations submitted by NHS Highland attached at Appendix 1 and a further assessment of crime statistics submitted by Police Scotland attached at Appendix 2, the Board is invited to agree options in relation to proposals for an Overprovision Statement on which to consult statutory consultees and the public and to agree an appropriate consultation period. 1. Background 1.1 On 7 August 2013, the Board agreed proposals for the process of developing a statement under section 7 of the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005 (the “Act) as to the extent to which the Board considers there to be overprovision of licensed premises, or licensed premises of a particular description, in any locality within the Board’s area. This process involved first ingathering evidence, where available, in relation to all of the five licensing objectives, with the assistance, in particular, of NHS Highland and Northern Constabulary – now part of Police Scotland. 1.2 The ingathering and analysis of evidence has taken longer than was initially anticipated and has not been an easy task. This is particularly because of the differences in the way in which data on alcohol-related harm is and has been collected by the various agencies in Highland, some being collected at intermediate geography/data zone level but some being collected at multimember ward level or, in the case of crime statistics, at police area level or police beat level. -

The Book of the Feill

wIM miì&^ c mj^ '^J. THE BOOK OF THE FEILL MARLBOROUGH HOUSE P.UJL MAJLL, I am glad to accede to the request made to me by the Edinburgh Highland Feill Committee to send a message of good wishes for reproduction in the "Book of the Feill". I wish the undertaking all possible success, and trust that through its means all necessary comforts for our gallant Highlanders serving at the Front will be provided for them. THE BOOK OF THE FEILL A MEMENTO OF THE FEILL HELD IN THE MUSIC HALL, EDINBURGH, FOR THE PURPOSE OF PROVIDING COMFORTS FOR THE SOLDIERS OF OUR HIGHLAND REGIMENTS 29TH-31ST MARCH 1917 ISSUED BV THE ASSOCIATION OF HIGHLAND SOCIETIES OF EDINBURGH EDITORS FRED. T. MACLEOD DAVID MACRITCHIE W. G. BURN MURDOCH Coiitents •AGE Letter from Hek Majesty Queen Alexandka . • • 5 Intkoduction ..... Fred. T. MacLeod ii DosT Thou Rememukk? . Norman MacLeod, D.D. i6 Born 1S12: Dicd 1872 OuK HiGHLAND Regiments . John Bartholoìnew i8 A HiGHLAND Marching Song . Akxaiider Nicolsofi 26 Trade and Trade Conditions in the Town and County ok Inverness IN THE Olden Times . WilHam Mackay, LL.D. 30 Lettek fkom the Right Honoukahle Roiìekt Munko, K.C, Secretaky for scotland . -39 HoME ...... Mary Adavison 40 MOLADH NA PÌOBA ..... Eoiii Mac Aileiiì {transliterated by E. C. C. Watson) 42 PiPiNG OvERSEAS . W. G. Burn Murdoch 44 The Old Home Hearth .... Mary Adamson 58 In Memoriam : The Rev. J. Campbell MacGregor, V.D., F.R.G.S. A Friend 61 The White Swan of Erin . Kenneth Macleod 65 GuALAiNN Ri GuALAiNN . , . Malcolm MacLennan, D.D. -

HLUEDG 1995 Ardnamurchan and Morvern Programme

HILL LAND USE AND ECOLOGY DISCUSSION GROUP MEETING TUESDAY 16 MAY TO THURSDAY 18 MAY 1995 ARDNAMURCHAN AND MORVERN Outline details were sent out in early January and I thank all those who responded with a firm booking. The programme is now complete and details are shown below. Group transport will be provided by a local coach operator who knows the narrow roads in the area well. Timings are shown for guidance but r every effort will be made to keep clo :e to them if everything is to be achieved on the programme. The Strontian Hotel will be the base for evening meals and talks. PROGRAMME TUESDAY 16TH - details of each individual's accommodation are shown on the separate note with Strontian village plan overleaf. Meet at the Strontian Hotel from 1800 after checking into your accommodation. Dinner 1930 followed by : Evening talk on Sunart to Ardnamurchan Dr Ian Strachan - currently seconded to EC Habitats Directive project in Lochaber previously Area Officer, South Lochaber. Ian will be with the group during the field trip to Ardnamurchan on the following day. WEDNESDAY 17TH - 08.45 Coach departs from Strontian Hotel. Travel to Salen to look at new road junction and widening scheme where sensitive management of important woodlands was necessary during the construction phase. (Approx 0915 to 0945). Continue on narrow road" to Gl eribort odaia ViSIlOh CaN'iKa. en ; OULC rSH will describe some of the other road widening proposals currently in hand. GLENBORRODALE VISITOR Centre operated by Michael and Karen MacGregor. An opportunity to see the new and innovative extension, probably the first group to do so following completion (almost!). -

Western Scotland

Soil Survey of Scotland WESTERN SCOTLAND 1:250 000 SHEET 4 The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research Aberdeen 1982 SOIL SURVEY OF SCOTLAND Soil and Land Capability for Agriculture WESTERN SCOTLAND By J. S. Bibby, BSc, G. Hudson, BSc and D. J. Henderson, BSc with contributions from C. G. B. Campbell, BSc, W. Towers, BSc and G. G. Wright, BSc The Macaulay Institute for Soil Rescarch Aberdeen 1982 @ The Macaulay Institute for Soil Research, Aberdeen, 1982 The couer zllustralion is of Ardmucknish Bay, Benderloch and the hzlk of Lorn, Argyll ISBN 0 7084 0222 4 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS ABERDEEN Contents Chapter Page PREFACE vii ACKNOWLEDGE~MENTS ix 1 DESCRIPTIONOF THEAREA 1 Geology, landforms and parent materials 2 Climate 12 Soils 18 Principal soil trends 20 Soil classification 23 Vegetation 28 2 THESOIL MAP UNITS 34 The associations and map units 34 The Alluvial Soils 34 The Organic Soils 34 The Aberlour Association 38 The Arkaig Association 40 The Balrownie Association 47 The Berriedale Association 48 The BraemorelKinsteary Associations 49 The Corby/Boyndie/Dinnet Associations 49 The Corriebreck Association 52 The Countesswells/Dalbeattie/PriestlawAssociations 54 The Darleith/Kirktonmoor Associations 58 The Deecastle Association 62 The Durnhill Association 63 The Foudland Association 66 The Fraserburgh Association 69 The Gourdie/Callander/Strathfinella Associations 70 The Gruline Association 71 The Hatton/Tomintoul/Kessock Associations 72 The Inchkenneth Association 73 The Inchnadamph Association 75 ... 111 CONTENTS -

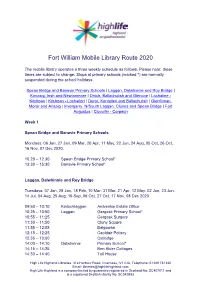

Fort William Mobile Library Route 2020

Fort William Mobile Library Route 2020 The mobile library operates a three weekly schedule as follows. Please note: these times are subject to change. Stops at primary schools (marked *) are normally suspended during the school holidays. Spean Bridge and Banavie Primary Schools | Laggan, Dalwhinnie and Roy Bridge | Kincraig, Insh and Newtonmore | Onich, Ballachulish and Glencoe | Lochaline - Kilchoan | Kilchoan - Lochailort | Duror, Kentallen and Ballachulish | Glenfinnan, Morar and Arisaig | Invergarry, N/South Laggan, Clunes and Spean Bridge | Fort Augustus | Clovullin - Corpach Week 1 Spean Bridge and Banavie Primary Schools Mondays: 06 Jan, 27 Jan, 09 Mar, 20 Apr, 11 May, 22 Jun, 24 Aug, 05 Oct, 26 Oct, 16 Nov, 07 Dec 2020. 10.20 – 12.30 Spean Bridge Primary School* 13:30 – 15:30 Banavie Primary School* Laggan, Dalwhinnie and Roy Bridge Tuesdays: 07 Jan, 28 Jan, 18 Feb, 10 Mar, 31 Mar, 21 Apr, 12 May, 02 Jun, 23 Jun, 14 Jul, 04 Aug, 25 Aug, 15 Sep, 06 Oct, 27 Oct, 17 Nov, 08 Dec 2020. 09:50 – 10:10 Kinlochlaggan Ardverikie Estate Office 10:25 – 10:50 Laggan Gergask Primary School* 10:55 – 11:25 Gergask Surgery 11:30 – 11:50 Cluny Square 11:55 – 12:05 Balgowan 12:15 – 12:25 Caoldair Pottery 12:35 – 13:00 Catlodge 14:00 – 14:10 Dalwhinnie Primary School* 14:15 – 14:25 Ben Alder Cottages 14:30 – 14:40 Toll House High Life Highland Libraries, 31a Harbour Road, Inverness, IV1 IUA, Telephone: 01349 781340 Email: [email protected] High Life Highland is a company limited by guarantee registered in Scotland No. -

125217081.23.Pdf

u, uiy. (Formerly AN DEO GREINE) 'dSfie Montdly Magazine of Jin (Somunn tfaiddealaefy Volume XLI. October, 1945, to September, 1946, inclusive. AN COMUNN GAIDHEAIvACH, 131 West Regent Street, Glasgow. -e-S CONTENTS. -8^ GAELIC DEPARTMENT. PAGE Am Fear Deasachaidh— D.D. airson ar Fear deasachaidh 84 Am B.B.C. agus a’ Ghaidhlig 47 Eadar sinn fhein, 45, 55, 05, 75, 84, An Riaii Orpine ...... 37 94, 115. An t-Urr, Calum MacLeoid 87 Facal san cjealachadh 66 Ar Duthaich agus ar Daoine 98 Facal san dol seachad, 2, 10, 18, 28, Biadh is Beoshlaint 37 38, 48, 58, 68, 78, 98, 109. Canain Bheo 27 Failte air an t-Saighdear 84 Comhfhurtachd agus cainnt 07 Leabhraichean 43 Cor na G&idhlig an diugh 107 Litir Comunn na h-Oigridh, 6, 13, 21 Gh&idhlig Bhretonach, A’ 17 31, 40, 50, 00, 70, 79^89, 99, 109. Latha Ghlinn Fhionghuin 1 Maoin Litreachas G&idhlig, 7, 10. 20, Rathaidean agus Uidheaman-giulain 9 36, 46, 56, 66, 95. Slighean nan Eilean 77 Oisinn na h-Oigridh 100, 110 Air a’ Chnoc 25, 34, 44, 54, 04 Seanchas 11 - Air an Duthaich 36 54 Sgeulachd bheag ... H2 An t-Ard Mharaiche Dearg 25 Sgeulachdan o’n Lochlannais 15 Bas Chairdean 7, 33, 30, 115 Sgiobaireachd 1' l Coinneach Odhar Fiosaiche ...... 114 Suiaire, An 112 Cothrom is Anacothrom 84 Bardachd. PAGE A’ Bbeinn 36 Gleann Comhann 15 Aile na Mara 0 lonndrainn Cuain 113 Alltan Beinn 74 lorriacheist 84 An Eala Aonranach 83 Leannan 43 An Gradh 90 Leig dhiot t’ lomagain 84 An Guth 04 MJiag mo Reusan - =.•- An t-Ailleagan 24 Miami an Fhogarraich do’n Eilean An t-Urr. -

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS and FIGURES 1996-97

Scottish Natural Heritage FACTS AND FIGURES 1996-97 Working with Scotland’s people to care for our natural heritage PREFACE SNH Facts and Figures 1996/97, contains a range of useful facts and statistics about SNH’s work and is a companion publication to our Annual Report. SNH came into being on 1 April 1992, and in our first Annual Report we published an inventory of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs). After an interval of five years it is appropriate to now update this inventory. We have also provided a complete Scottish listing of National Nature Reserves, National Scenic Areas, European sites and certain other types of designation. As well as the information on sites, we have also published information on our successes during 1996/97 including partnership funding of projects, details of grants awarded, licences issued and our performance in meeting our standards for customer care. We have also published a full list of management agreements concluded in 1996/97. We hope that those consulting this document will find it a useful and valuable record. We are committed to being open in the way we work and if there is additional information you require, contact us, either at any local offices (detailed in the telephone directory) or through our Public Affairs Branch, Scottish Natural Heritage, 12 Hope Terrace, Edinburgh EH9 2AS. Telephone: 0131 447 4784 Fax: 0131 446 2277. Table of Contents LICENCES 1 Licences protecting wildlife issued from 1 April 1996 to 31 March 1997 under various Acts of Parliament 1 CONSULTATIONS 2 Natural -

Dale Cottage Glenborrodale, Archaracle, Argyll

Dale Cottage Glenborrodale, Archaracle, Argyll Dale Cottage Glenborrodale, Archaracle, Argyll, PH36 4JP An attractive cottage on the stunning Ardnamurchan Peninsula overlooking Glenborrodale Bay. Salen 7 miles, Fort William 40 miles, Inverness 118 Miles, Glasgow 132 miles (All distances are approximate) Entrance hall | Sitting room (with wood burning stove)| Kitchen | Family bathroom | Boot room Three bedrooms | Shower room Front and rear garden with attractive burn Shed with 30kW biomass boiler Wonderful views overlooking Glenborrodale Bay About 0.28 Acres Oban Edinburgh Gibraltar Street, Oban, Argyll 80 Queen Street, Edinburgh PA34 4AY EH2 4NF Tel: 01631 705 480 Tel: 0131 222 9600 [email protected] [email protected] theestatesofficeargyll.com knightfrank.co.uk Situation Dale Cottage is situated on the southern shores of the stunning Ardnamurchan Peninsula with wonderful views overlooking Glenborrodale Bay on Loch Sunart and the Movern Hills beyond. The nearby villages of Salen (7 miles) and Acharacle (9½ miles) have a range of local services including several shops, medical practice, dentist surgery, hotels, restaurants, pubs and a primary school. There is a secondary school in Strontian (16 miles). More extensive services can be found in Fort William (40 miles). The countryside around Dale Cottage is some of the most spectacular in Scotland, a fantastic base for exploring the peninsula with a great variety of outdoor activities available. Fishing, sailing, mountain biking, kayaking, and whale watching are all available nearby. As well as an outstanding coastline, there is an abundance of wildlife in the area including otters, seals, porpoises, deer, golden and white- tailed eagles. Description Dale Cottage is a traditional stone constructed cottage situated on the southern shores of the Ardnamurchan Peninsula. -

HMS Dorlin Timeline

rd HMS Dorlin and the 3 British Infantry Division. HMS Dorlin was a wartime naval shore establishment based on six estate houses; Dorlin, Roshven, Shielbridge, Salen, Glencripesdale and Glenborrodale. They are located in the extreme south of an isolated area between Loch Hourn and Loch Shiel called The Rough Bounds, comprising Knoydart, Morar, Arisaig and Moidart. In the 18th Century it was largely Catholic and Jacobin, with ownership disputed between the Macdonalds of Clanranald, whose traditional seat was Castle Tioram that dates from the 13th Century, and the Macdonells of Glengarry. Both claimants were descendants of the 12th Century King Somerled (Summer Traveller which is a kenning for Viking), whose dynasty became The Lord of the Isles, who was subservient only to the Kings of England and Scotland. The present titular holder is Charles, Prince of Wales. After the 1745 rebellion the government recruited highland regiments who, by accepting the Hanoverian King's shilling, were 'suborned' and lost the temptation to revolt. Like the rest of the Highlands, the Rough Bounds were largely denuded of people during the 19th Century Highland Clearances to the benefit of PEI and Nova Scotia in Canada, becoming as a result a vast sheep ranch and preserve of the rich for hunting, shooting & fishing. The land on which Dorlin House was built belonged in 1811 to Ranald George Macdonald, 19th Chief of the Clan Macdonald of Clanranald and MP. He had become an associate of the extravagant and dissolute Prince Regent, and to fund his lifestyle sold for £213,211 all of the traditional lands he had inherited except the ruinous Castle Tioram. -

Ardnamurchan Peninsula, Highland

Ardnamurchan Peninsula, Argyll and Bute The Ardnamurchan Peninsula is one of the best areas for watching mammals in Britain. With a bit of luck Wildcat, Pine Marten, Otter and a diverse selection of other species may be seen. Ardnamurchan Peninsula is best reached via the Corran-Ardgour ferry, off the A82, 13 miles south of Fort William. Otters are occasionally seen from the ferry. From Ardgour, drive south-west along Loch Linne (both Grey Seal and Common Seal can be seen on the rocks along this stretch of road) and then west through Glen Tarbert along the B861. Shortly before you reach Strontian you reach the start of Loch Sunart. Otters occur in this area. From Strontian continue west along Loch Sunart (B861) through Ardnastang and Resipole to Salen. It is worth stopping several times to scan for seals, Otters, and Harbour Porpoise, which has been seen as far east as Salen. Water Shrews also occur on the shore of Loch Sunart to the east of Salen. American Mink occur commonly along Loch Sunart. In Salen turn left on the B8007 towards Glenborrodale and Point of Ardnamurchan. The road continues to skirt Loch Sunart and it is worth stopping regularly to look for seals, Otters etc. After seven miles or so the road goes through Glenborrodale where Pine Marten have reared young in the roof of the hotel. Two miles further west you pass the Glenmore Natural History Centre on the left (NM.586.624). It is worth stopping here (open from early May to late September) to ask about recent sightings. -

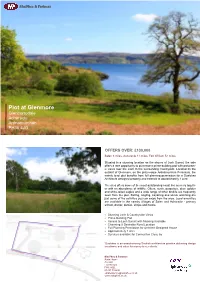

Plot at Glenmore, Glenborrodale

MacPhee & Partners Plot at Glenmore Glenborrodale Acharacle Ardnamurchan PH36 4JG OFFERS OVER: £130,000 Salen 9 miles. Acharacle 11 miles. Fort William 52 miles. Situated in a stunning location on the shores of Loch Sunart, the sale offers a rare opportunity to purchase a prime building plot with panoram- ic views over the Loch to the surrounding countryside. Located on the outskirt of Glenmore, on the picturesque Ardnamurchan Peninsula, the mainly level plot benefits from full planning permission for a Dualchas Architects designed property and extends to approximately 1 acre. The area offers some of the most outstanding coast line scenery togeth- er with an abundance of wildlife. Otters, seals, porpoises, deer, golden and white -tailed eagles and a wide range of other birdlife are frequently seen from the plot. Sailing, angling, kayaking and whale watching are just some of the activities you can enjoy from the area. Local amenities are available in the nearby villages of Salen and Acharacle - primary school, doctor, dentist, shops and hotels. • Stunning Loch & Countryside Views • Prime Building Plot • Access to Loch Sunart with Mooring Available • Charming & Desirable Rural Location • Full Planning Permission for Architect Designed House • Approximately 1 Acre • Services available for Connection Close by ‘Dualchas is an award -winning Scottish architecture practice delivering design excellence and value for money to our clients.’ MacPhee & Partners Airds House An Aird Fort William PH33 6BL 01397 702200 [email protected] www.macphee.co.uk Planning Permission Full Planning Permission was granted on 13 th May 2015 Side Elevation (Ref:15/00736/FUL) for the erection of an architect de- signed dwellinghouse. -

Fort William & Lochaber

EXPLORE 2020-2021 Outdoor Capital of the UK fort william & lochaber An Gearasdan & Loch Abar visitscotland.com Contents 2 Fort William & Lochaber at a glance 4 Great outdoors 6 Amazing adventures 8 Dramatic history 10 Wonderfully wild 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 37 Leisure activities Welcome to… 44 Shopping 45 Food & drink fort william 49 Tours 54 Transport & lochaber 54 Events & festivals Fàilte chun 55 Accommodation An Ghearasdan 66 Regional map & Loch Abar Fort William is known as the ‘Outdoor Capital of the UK’ for several very exciting reasons. The area has Britain’s highest mountain, two ski resorts, a World Cup mountain bike course, the world’s biggest indoor ice climbing wall and is the end of the West Highland Way and the start of the Great Glen Way. Of course, you don’t have to be an adrenaline junkie to enjoy yourself here. We also have rare wildlife, exquisite seafood and spectacular views round every corner. We certainly have a Cover: The Sgurr of Eigg past that’s packed with intrigue, achievement Above: Stob Dearg and exploration for you to marvel at. Credits: © VisitScotland. It’s a particularly exciting time to visit with Kenny Lam, SnowScotland/ Scotland’s Highlands and Islands having been Steven McKenna, Ian Rutherford, named a top region in Lonely Planet’s Best in Paul Tomkins, Grant Paterson, Travel in 2019. David N Anderson, Cutmedia, Alexander Insch, Airborne Lens 20HFW Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM).