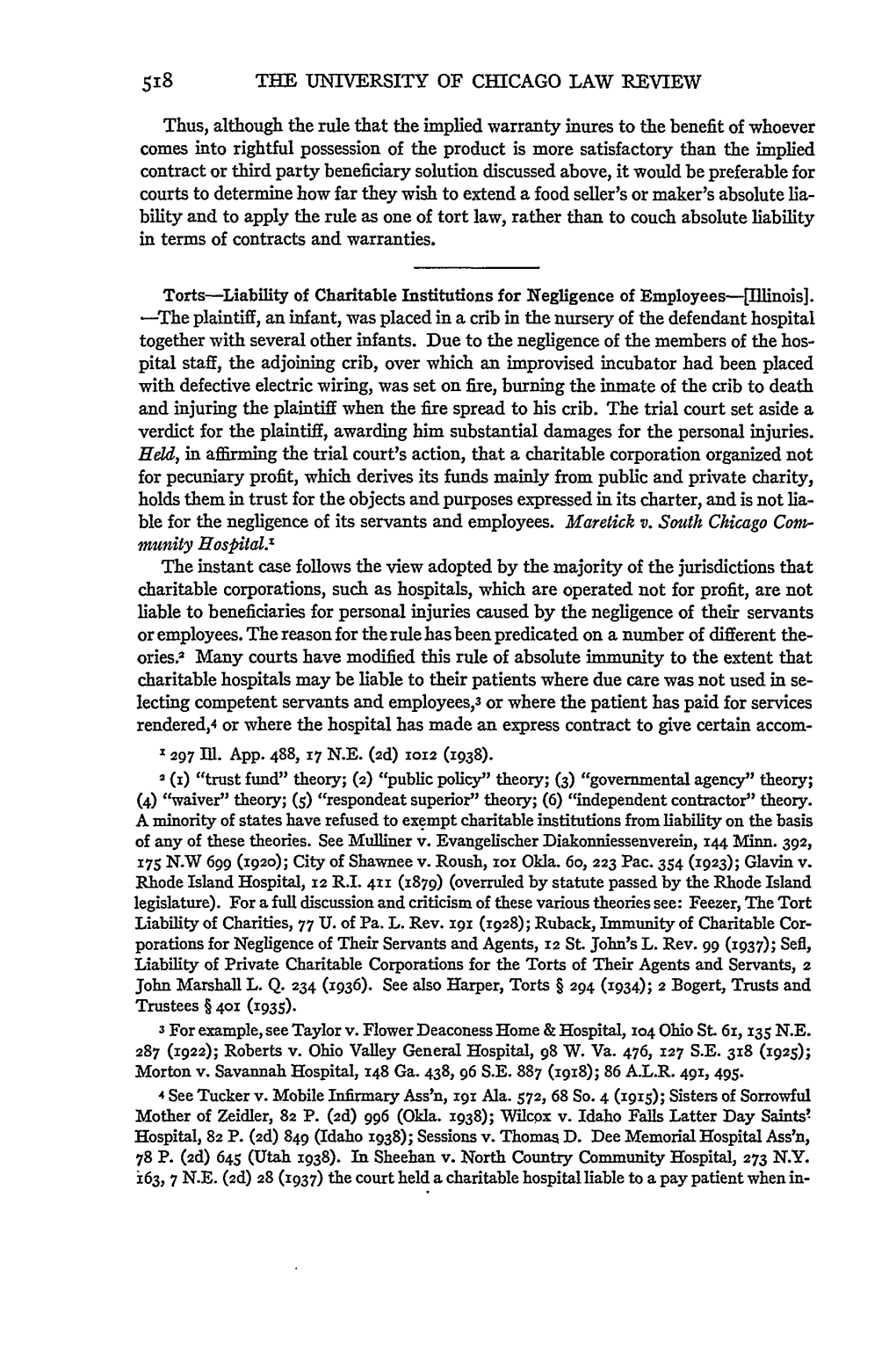

Torts. Liability of Charitable Institutions for Negligence of Employees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Health Network, Inc

PRELIMINARY OFFERING MEMORANDUM DATED FEBRUARY 1, 2018 NEW ISSUE Standard & Poor’s: “A” BOOK-ENTRY ONLY Moody’s: “A2” See “RATINGS” $202,000,000* COMMUNITY HEALTH NETWORK, INC. Taxable Bonds, Series 2018A Dated: date of delivery Due: as shown below Community Health Network, Inc., an Indiana nonprofit corporation (“CHNw”), will issue its Taxable Bonds, Series 2018A (the “Series 2018A Bonds”), pursuant to a Trust Indenture by and between CHNw and The Bank of New York Mellon Trust Company, N.A., as trustee (the “Bond Trustee”), dated as of February 1, 2018. Interest on the Series 2018A Bonds will accrue from their date of delivery and will be payable on May 1 and November 1 of each year, commencing May 1, 2018. See “SERIES 2018A BONDS−General.” The Series 2018A Bonds will be issued as fully registered bonds without coupons, in denominations of $1,000 or any integral multiple thereof, and, when issued, will be registered in the name of Cede & Co., as nominee for The Depository Trust Company (“DTC”), New York, New York. DTC will act as the initial securities depository for the Series 2018A Bonds. So long as Cede & Co. is the registered owner of the Series 2018A Bonds, as nominee of DTC, references herein to the owners or holders of the Series 2018A Bonds mean Cede & Co., as nominee for DTC, and not the Beneficial Owners (as hereinafter defined) of the Series 2018A Bonds. See “SERIES 2018A BONDS–Book-Entry Only System.” The Series 2018A Bonds are general obligations of CHNw. Payment of the principal of and premium, if any, and interest on the Series 2018A Bonds is secured by certain payments to be made by the Obligated Group Members (as hereinafter defined) under a Master Note Obligation, Series 2018A (the “Series 2018A Note”), to be issued by CHNw under an Amended and Restated Master Trust Indenture by and between the Obligated Group Members and The Bank of New York Mellon Trust Company, N.A., as successor master trustee, dated as of November 27, 2012, as supplemented and amended to date. -

MEDICAL RELIEF 2020-21 • Anjuman Islamia Medical and Social Service

MEDICAL RELIEF 2020-21 Anjuman Islamia Medical and Social Service Society, Ranchi – East Central Zone – Jamshedpur DO Anjuman Islamia Medical and Social Service Society hospital caters to all sections of people at affordable cost. Hospital has facility of general medicine, general surgery, orthopedic, pediatric, gynecology, skin, ENT, physiotherapy and dental health. Hospital has 40 doctors including 5 duty doctors and 66 other staff for taking care of the patients. On an average 250 to 350 patients per day are being treated at the hospital. 15 to 35 patients are treated free of cost per month. For poor patients the governing body helps with “Jakat”maximum Rs 10,000/- per patient. The project sought financial assistance for Cardio- Ambulance to bring patients and to refer critical patients to higher centre. Cardio – Ambulance will act as an extra ICU movable bed for the hospital. Financial assistance of ` 25,00,000/- has been provided for purchase of Ambulance. SDA Diamond Hospital & Medical Research Centre -Western Zone –Surat DO SDA – Diamond Hospital & Medical Research Centre, Surat founded in February 2014, is a multispecialty charitable trust hospital with 150 beds, 4 operation theatres including 2 modular OTs and 15 beds ICU and 16 beds NICU. Hospital’s high quality services attract patients from Surat and its periphery. On an average there is more than 70% occupancy in the hospital as inpatients, about 350-400 people come through the O.P.D daily for medical relief.They are offering free normal delivery if baby girl is born and for second baby girl they handover a Bond of Rs. -

LIST of LICENSED BLOOD BANKS in INDIA * (February, 2015)

LIST OF LICENSED BLOOD BANKS IN INDIA * (February, 2015) Sr. State Total No. of Blood Banks No. 1. Andaman and Nicobar Islands 03 2. Andhra Pradesh 140 3. Arunachal Pradesh 13 4. Assam 76 5. Bihar 84 6. Chandigarh 04 7. Chhattisgarh 49 8. Dadra and Nagar Haveli 01 9. Daman and Diu 02 10. Delhi (NCT) 72 11. Goa 05 12. Gujarat 136 13. Haryana 79 14. Himachal Pradesh 22 15. Jammu and Kashmir 31 16. Jharkhand 54 17. Karnataka 185 18. Kerala 172 19. Lakshadweep 01 20. Madhya Pradesh 144 21. Maharashtra 297 22. Manipur 05 23. Meghalaya 07 24. Mizoram 10 25. Nagaland 06 26. Odisha(Orissa) 91 27. Puducherry 18 28. Punjab 103 29. Rajasthan 102 30. Sikkim 03 31. Tamil Nadu 304 32. Telangana 151 33. Tripura 08 34. Uttar Pradesh 240 35. Uttarakhand 24 36. West Bengal 118 Total 2760 * List as received from the Zonal / Sub-Zonal Offices of CDSCO. Sr. No Sr.No Name and address of the Blood bank Central-wise State-wise (1). ANDAMAN & NICOBAR 1. 1) M/s G.B Pant Hospital, Atlanta Point, Port Blair-744104 2. 2) M/s I.N.H.S. Dhanvantri, Minni Bay, Port Blair-744103 3. 3) M/s Pillar Health Centre, Lamba Line, P.B. No.526, P.O.- Junglighat, Port Blair-744103 (2). ANDHRA PRADESH 4. 1) A.P.Vidya Vidhana Parishad Community Hospital Blood Bank, Hospital Road, Gudur-524101, Nellore Dist. 5. 2) A.S.N. Raju Charitable Trust Blood Bank, Door No. 24-1-1, R.K. Plaza (Sarovar Complex), J.P. -

The Community Benefit Standard for Non-Profit Hospitals: Which Community, and for Whose Benefit?

Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 5 2007 The Community Benefit Standard for Non-Profit Hospitals: Which Community, and for Whose Benefit? Cecilia M. Jardon McGregor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp Recommended Citation Cecilia M. McGregor, The Community Benefit Standard for Non-Profit Hospitals: Which Community, and for Whose Benefit?, 23 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol'y 302 (2007). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/jchlp/vol23/iss2/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Contemporary Health Law & Policy (1985-2015) by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE COMMUNITY BENEFIT STANDARD FOR NON-PROFIT HOSPITALS: WHICH COMMUNITY, AND FOR WHOSE BENEFIT? Cecilia M. Jardon McGregor INTRODUCTION Patients often distinguish hospitals based on whether the care provided will be covered under their health insurance policy, if a particular doctor has privileges, or if the hospital is close and easily accessible to them.' Many patients need not worry about the financial impact of their choice of hospital beyond ensuring that their care will be covered by insurance. However, for patients without insurance or with inadequate insurance, choosing a hospital based only on doctors' privileges or location can have far-reaching and severe financial and legal consequences. For these patients, the hospital's corporate form and whether it qualifies as a charity for tax purposes can be most important. Non-profit hospitals and other health care facilities (non- profit health care organizations) that qualify as charities receive beneficial tax treatment from federal, state and local governments. -

Liability of Charitable Associations in Ohio

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 8 Issue 2 Article 8 1957 Liability of Charitable Associations in Ohio David Freed Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David Freed, Liability of Charitable Associations in Ohio, 8 W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 194 (1957) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol8/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. WESTERN RESERVE LAW REVIEW [March Liability of Charitable Associations in Ohio INTRODUCTION The question of whether a charitable association should be immune from tort liability has created a great difference of opinion among Ameri- can courts. Unlike most problems in the field of torts, each side of -the question supports its arguments in what may be termed "social justice." Which view will better serve the needs of a complex modern community is the heart of the problem. Those who would grant immunity from tort liability point to the great community benefit flowing from these associations. They urge that by their very nature charities are entitled to every legal benefit which the courts can properly give them. It is their position that the charitable association will be better able to serve the general community if it is not hampered financially and administratively by tort claims. -

COMMONSENSE Volume 20, Issue 1 January/February 2013

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE COMMONSENSE VOLUME 20, ISSUE 1 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013 19th Annual Scientific Assembly www.AAEM.org Las Vegas, Nevada February 9-13, 2013 INSIDE President’s Message From the Editor’s On-site Desk Registration Washington Watch Available! Foundation Donations AAEM News Upcoming Conferences YPS News AAEM/RSA News Job Bank Celebrating Permit No. 1310 No. Permit WI ilwaukee, M ID PA S Postage S U 53202-3823 WI ilwaukee, M ail M Standard ells Street / Suite 1100 Suite / Street ells W ast E 555 Pre-Sorted E S SEN 1993-2013 COMMON JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2013 COMMONSENSE 1 COMMONSENSE Table of Contents President’s Message .........................................................................................................................3 From the Assistant Editor’s Desk .......................................................................................................4 Letters to the Editor – New! ...............................................................................................................5 Washington Watch ............................................................................................................................6 Foundation Donations .......................................................................................................................6 Officers AAEM News President William T. Durkin, Jr., MD MBA The Business of Emergency Medicine .....................................................................................9 Vice President Law -

Financial Impact of Nosocomial Infections in the Intensive Care Units

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Glaucio de Oliveira Nangino1, Cláudio Dornas de Oliveira1, Paulo César Correia1, Noelle de Melo Financial impact of nosocomial infections in the Machado1, Ana Thereza Barbosa Dias1 intensive care units of a charitable hospital in Minas Gerais, Brazil Impacto financeiro das infecções nosocomiais em unidades de terapia intensiva em hospital filantrópico de Minas Gerais 1. Santa Casa de Belo Horizonte - Belo Horizonte ABSTRACT who had nosocomial infections (MG), Brazil. associated with the intensive care unit. Objective: Infections in intensive The median cost per admission and the care units are often associated with a high length of stay for all the patients sampled morbidity and mortality in addition to were R$1.257,53 and 3 days, respectively. high costs. An analysis of these aspects Compared to the patients without an can assist in optimizing the allocation of infection, the patients with an infection relevant financial resources. had longer hospital stays (15 [11-25] Methods: This retrospective study versus 3 [2-6] days, p<0.01), increased analyzed the hospital administration costs per patient in the intensive care and quality in intensive care medical unit (median R$9.763,78 [5445.64 - databases [Sistema de Gestão Hospitalar 18,007.90] versus R$1.093,94 [416.14 - (SGH)] and RM Janus®. A cost analysis 2755.90], p<0.01) and increased was performed by evaluating the medical costs per day of hospitalization in the products and materials used in direct intensive care unit (R$618,00 [407.81 - medical care. The costs are reported in 838.69] versus R$359,00 [174.59 - the Brazilian national currency (Real). -

Strengthening Healthy Communities Minnesota’S Hospitals: Strengthening Healthy Communities Minnesota Hospitals’ Community Contributions Total $4.2 Billion

2014 Community Benefit Report Minnesota’s hospitals: Strengthening healthy communities Minnesota’s hospitals: Strengthening healthy communities Minnesota hospitals’ community contributions total $4.2 billion Minnesota’s hospitals and health systems are under-insured or government-insured residents; years ahead. Through these Community Health driven by a mission to provide high quality health community health services and initiatives; Needs Assessments, hospitals are able to develop care that extends beyond the hospital’s walls. health education and wellness programs; and tailored approaches that are as unique and diverse As nonprofits, Minnesota hospitals are dedicated more. In 2013, Minnesota hospitals provided as the communities themselves. to promoting and improving the health of local more than $4.2 billion in contributions to their communities and their residents by providing communities, while providing care for 549,605 We know that much of what influences our health a range of vital services to meet the unique inpatient admissions, more than 11.3 million happens outside of the doctor’s office — in needs of the communities they serve. These outpatient registrations and more than 1.8 million our schools, workplaces and neighborhoods. include free or discounted care for the uninsured, emergency room visits. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than half of all Americans As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable live with a preventable chronic disease, many of What are community benefits? Care Act (ACA), each charitable hospital partners which are related to obesity, poor nutrition and Community benefits are health care- with their community to assess the health needs lack of physical exercise. -

AMA Journal of Ethics® March 2019, Volume 21, Number 3: E207-214

AMA Journal of Ethics® March 2019, Volume 21, Number 3: E207-214 CASE AND COMMENTARY Should Hospital Emergency Departments Be Used as Revenue Streams Despite Needs to Curb Overutilization? Alex Myers, Aaron Cain, Berkeley Franz, PhD, and Daniel Skinner, PhD Abstract This case asks how a hospital should balance patients’ health needs with its financial bottom line regarding emergency department utilization. Should hospitals engage in proactive population health initiatives if they result in decreased revenue from their emergency departments? Which values should guide their thinking about this question? Drawing upon emerging legal and moral consensus about hospitals’ obligations to their surrounding communities, this commentary argues that treating emergency departments purely as revenue streams violates both legal and moral standards. Case General Hospital, located in a downtown urban center, serves a wide variety of patients from its immediate neighborhood and surrounding suburbs and counties. A significant percentage of the patient population is drawn from General’s adjacent blocks, where the community has high rates of poverty and crime and many residents tend to have poor health status. Traditionally, General’s programs offer charity care to local, underserved patients. Dr Z, a health professional and senior executive, meets quarterly with each department to discuss successes, challenges, and plans moving forward. One particular area of concern has been emergency department overutilization. During this meeting, Dr X, director of emergency medicine, and Dr Y, a third-year emergency medicine resident, propose a plan to address overutilization. Dr Y presents data on asthma-related emergency department visits, which illustrates that most patients with asthma-related complaints have lower-than-average household incomes and come from demographically similar neighborhoods within 3 miles of General’s campus. -

2013 Community Health Needs Assessment

_____________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................2 Overview of Providers, Services, and Facilities ..................................................................................3 Assessment Methodology ..................................................................................................................4 Demographic Information .................................................................................................................9 Health Indicators and Outcomes .......................................................................................................10 Survey Results ....................................................................................................................................16 Findings of Key Informant Interviews and Focus Group....................................................................40 Priority of Health Needs.....................................................................................................................46 Summary ............................................................................................................................................46 Appendix A – Survey Instruments ......................................................................................................49 Appendix B – Key Informants Participating in Interviews -

Nonprofit Hospital Billing of Uninsured Patients: Consumer-Based Class Actions Move to State Courts

NONPROFIT HOSPITAL BILLING OF UNINSURED PATIENTS: CONSUMER-BASED CLASS ACTIONS MOVE TO STATE COURTS David L. Nie• TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .•..••••••.••••.....•..•••••.•.•..••....••.....•••...•..•..•..••.......•••..•.. 173 II. A REVIEW OF NONPROFIT HOSPITALS AS TAX- EXEMPT 0RGANIZATIONS ............................................................... 178 A. Tax-Exempt Hospitals and the Provision ofCharity Care ....... l79 B. State and Local Interpretations ofCompeting Federal Standards for Tax-Exemption ..................................... l82 C. State Recognition ofthe Community Benefit Standard ................................................................................... 183 ill. RECENT SCRUTINY FROM THE EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE BRANCHES AND GRASSROOTS ORGANIZATIONS ............................ 186 A. Congressional Hearings Regarding the Tax-Exempt Health Sector ............................................................................ 186 B. State Legislatures Address the Charity Care Practices ofHospitals within Their Borders ........................................... 188 C. State Attorneys General Act on Their Role of Supervising Charitable Organizations ..................................... 189 D. Advocacy Groups Acting on behalfof Uninsured Patients ...... 190 IV. THE CONSUMER PROTECTION CLAIMS OF THE SUTTER HEALTH NONPROFIT HOSPITAL PRICING CLASS ACTION ............... 193 A. California's Consumers Legal Remedies Act ........................... 194 B. California's Unfair Competition Law ..................................... -

The Internal Revenue Service's "Contribution" to the Health Problems of the Poor

Catholic University Law Review Volume 21 Issue 1 Fall 1971 Article 3 1971 The Internal Revenue Service's "Contribution" to the Health Problems of the Poor Marilyn G. Rose Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Marilyn G. Rose, The Internal Revenue Service's "Contribution" to the Health Problems of the Poor, 21 Cath. U. L. Rev. 35 (1972). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol21/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Internal Revenue Service's "Contribution" to the Health Problems of the Poor Marilyn G. Rose* The existence of a health crisis in this, country is universally acknowledged. While the costs of medical and hospital care have far out-distanced the inflationary spiral in the consumer price index over the past decade, I the health status of the American population vis-a-vis the rest of the industrialized world has seriously deteriorated. 2 At the same time the public hospitals have become progressively more overcrowded, underfinanced and understaffed. In the past two years these hospitals have also faced threatened loss of accreditations, have been forced to shut down facilities and services, and have been sued by both * A.B., Brandeis University, LL.B., Harvard University, Chief Special Litigation, National Legal Program on Health Problems of the Poor. The author wishes to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Lawrence Hait, J.D., 1970, U.C.L.A., and George Schraer, J.D., 1970, U.C.L.A.