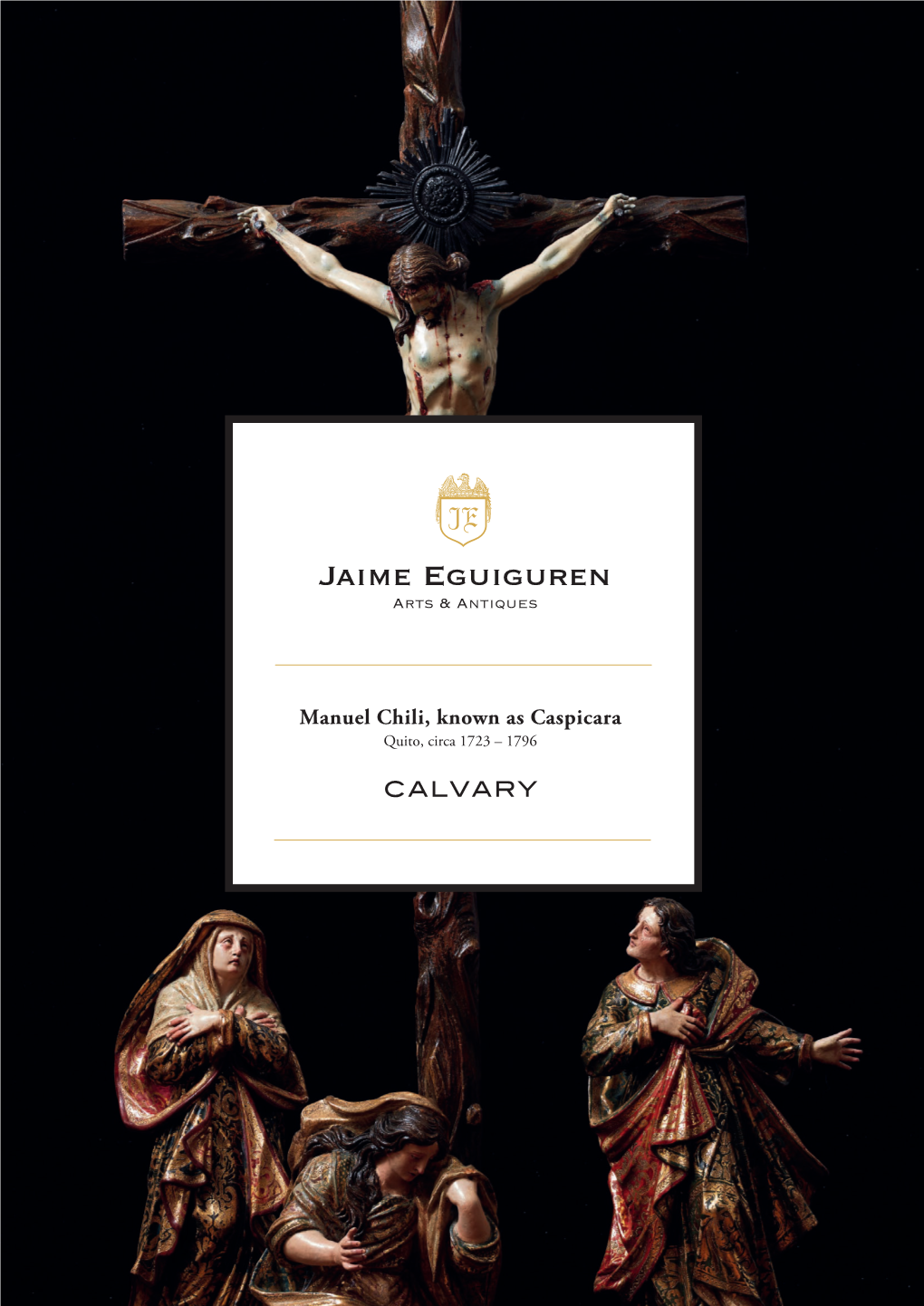

Manuel Chili, Known As Caspicara CALVARY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization and Analysis of the Mortars in the Church of the Company of Jesus—Quito (Ecuador)

minerals Article Characterization and Analysis of the Mortars in the Church of the Company of Jesus—Quito (Ecuador) M. Lenin Lara 1,2,* , David Sanz-Arauz 1, Sol López-Andrés 3 and Inés del Pino 4 1 Department of Construction and Architectural Technology, Polytechnic University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 2 School for the City, Landscape and Architecture, UIDE International University of Ecuador, Simón Bolívar Av. Jorge Fernández Av., Quito 170411, Ecuador 3 Mineralogy and Petrology Department, Complutense University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Arts, Design and Architecture, Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador, Quito 170411, Ecuador; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-593-994384851 Abstract: The Church of the Company of Jesus in Quito (1605–1765) is one of the most remarkable examples of colonial religious architecture on the World Heritage List. This church has multiple constructive phases and several interventions with no clear record of the entire architectural site, including the historical mortars. A total of 14 samples of coating mortars inside the central nave were taken, with the protocols suggested by the research team and a comparative sample of the architectural group that does not have intervention. The analysis presented in this paper focuses on mineralogical characterization, semi-quantitative analysis by X-ray diffraction and scanning electron microscopy with microanalysis of the samples. The results showed the presence of volcanic aggregate lime and gypsum, used in lining mortars and joint mortars. Mineralogical and textural composition Citation: Lara, M.L.; Sanz-Arauz, D.; data have allowed the mortar samples to be relatively dated. -

Bishop Peter Schumacher, CM

Vincentiana Volume 48 Number 6 Vol. 48, No. 6 Article 10 11-2004 From Exile to Glory: Bishop Peter Schumacher, C.M. (1839-1902) Adolfo Leon Galindo Pinilla C.M. Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Galindo Pinilla, Adolfo Leon C.M. (2004) "From Exile to Glory: Bishop Peter Schumacher, C.M. (1839-1902)," Vincentiana: Vol. 48 : No. 6 , Article 10. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vincentiana/vol48/iss6/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentiana by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VINCENTIANA 6-2004 - INGLESE February 14, 2005 − 2ª BOZZA Vincentiana, November-December 2004 From Exile to Glory: Bishop Peter Schumacher, C.M. (1839-1902) by Adolfo Leo´n Galindo Pinilla, C.M. Province of Colombia Introduction This article is not presented as a biography of Bishop Peter Schumacher, C.M., the second bishop of Portoviejo (Ecuador). Rather this essay is written as a pious remembrance of a venerable confrere and missionary. In his impenetrable ways, God led Fr. Schumacher on a courageous and self-sacrificing journey, making use of his meritorious life and enviable vocation. God led him from the arid desert, lacking in ideals (a place where we all find ourselves at different times if we become content with mediocrity) to the joy and fulfillment of imperishable glory, a glory to which he had always aspired. -

“Investigación De La Tecnología De La

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA EQUINOCCIAL FACULTAD DE ARQUITECTURA, ARTES Y DISEÑO CARRERA DE RESTAURACIÓN Y MUSEOLOGÍA TESIS PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN RESTAURACIÓN Y MUSEOLOGÍA “INVESTIGACIÓN DE LA TECNOLOGÍA DE LA PRODUCCIÓN DE LA OBRA ESCULTÓRICA DE CASPICARA, POR MEDIO DEL ESTUDIO TÉCNICO DEL CONJUNTO ESCULTÓRICO: “LA SABANA SANTA” UBICADA EN LA CATEDRAL DE QUITO.” GABRIELA STEPHANIA LARRIVA ORDÓÑEZ DIRECTOR: LICENCIADO JULIO MORALES QUITO, JUNIO, 2014 Universidad Tecnológica Equinoccial Gabriela Stephanía Larriva Ordóñez AUTORÍA Yo, Gabriela Stephania Larriva Ordóñez, declaro bajo juramento que el proyecto de grado titulado: “Investigación de la tecnología de la producción de la obra escultórica de Caspicara, por medio del estudio técnico del conjunto escultórico: “La Sabana santa” ubicada en la Catedral de Quito”. Es de mi propia autoría y no es copia parcial o total de algún otro documento u obra del mismo tema. Asumo la responsabilidad de toda la información que contiene la presente investigación. Atentamente, __________________________ Gabriela Stephanía Larriva Ordóñez II Universidad Tecnológica Equinoccial Gabriela Stephanía Larriva Ordóñez CERTIFICADO Por medio de la presente certifico que la Sra. Gabriela Stephanía Larriva Ordóñez, ha realizado y concluido su trabajo de grado, titulado: “Investigación de la tecnología de la producción de la obra escultórica de Caspicara, por medio del estudio técnico del conjunto escultórico: “La Sabana Santa” ubicada en la Catedral de Quito” para la obtención del título de, Licenciada en Restauración y Museología de acuerdo con el plan aprobado previamente por el Consejo de Investigación de la Facultad de Arquitectura, Artes y Diseño. De igual manera asumo la responsabilidad por los resultados alcanzados en el presente trabajo de titulación. -

The Indigenous Capilla De Cantuña: the Catholic Temple of The

Tulane Undergraduate Research Journal | Volume III (2021) The Indigenous Capilla de Cantuña: The Catholic Temple of The Sun Kevin Torres-Spicer Cal Poly Pomona, Pomona, California, USA ⚜ Abstract The Cantuña chapel within the St. Francis complex in Quito, Ecuador, was one of the first Catholic structures built in this region after the Spanish conquest in the sixteenth century. The chapel holds the name of its presumed native builder, Cantuña. However, a strong connection to the Incan sun deity, Inti, persists on this site. According to common belief and Spanish accounts, the Franciscan monks decided to build their religious complex on top of the palace temple of the Incan ruler, whom the natives believed to be Inti's incarnation. In this research, I examined vital components of the Capilla de Cantuña, such as the gilded altarpiece. I argue that the chapel acts as an Indigenous monument through the Cara, Inca, and Spanish conquests by preserving an aspect of native culture in a material format that transcends time. Most importantly, because the Cantuña chapel remains the least altered viceregal church in the region, it is a valuable testament to the various conquests and religious conversions of the Kingdom of Quito. Introduction wealth and discoveries back to Europe. 1 According to the Spanish Franciscans, a The Spanish conquest brought mendicant Catholic order which carried out Catholicism to the New World and took the evangelization of the Indigenous 1 Mark A. Burkholder and Lyman L. Johnson, Colonial Latin America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 37-43. Newcomb-Tulane College | 36 Tulane Undergraduate Research Journal | Volume III (2021) populations of the continent, the disastrous Scholarship often overlooks the previous results of the conquest were necessary for the ethnic communities since the Inca were the salvation of Indigenous souls.2 The Capilla group in charge during the Spanish arrival. -

Favors Attributed to Garcia Moreno

1 Favors Attributed to Gabriel Garcia Moreno1 One should not expect to consider all the following favors to be first class miracles, but as all being, indeed, the testimony of so many Catholic faithful who think that Garcia Moreno was a true saint and martyr. In the year 1938 a renewal of faith and confidence in the intercession of the President-martyr took place. Until now only three [of the following] cases could be evaluated as having the character of first class miracles, following the examination and approval of Holy Church. All that is contained in these pages in this respect is a reproduction of what is already edited in my books, Christian Hercules, Standard-bearer of the Heart of Jesus, Garcia Moreno. Is Garcia Moreno a Martyr? Knight of the Virgin, Fourteen Machete Blows and Six Bullet Wounds, Champion and Martyr of Progress, The Consecration, etc., which have all been published with ecclesiastical approval. Since these editions have sold out, it is fitting that these favors be recorded in the following pages. Patron of Travel Many travelers entrust their journeys to Garcia Moreno’s soul, remembering how that great man traveled along roads at the edges of cliffs, or infested with robbers. He forded torrential rivers, or went on marches while in bad health. The travelers, above all those from the province of Bolivar and the canton of Guano, offered stipends for Masses to be offered for this intention, and they declared that they were helped in an extraordinary way. The news of such favors reached the ears of Fr. -

Our Lady of Good Success

Volume 58 1 Reflections International Catholic Family Newsletter June 2020Sept What Is My Purpose‘ in Life? Our Lady Sent Us A Message From Ecuador 400 Years Ago The Miracle of the Statue of Our Lady of Good Success Passover 1451 BC - Deliverance Passover 2020 AD -Virus Deliverance Blessings to All: By: Richard Pickard Peace be with you. What is my Purpose in Life? To some extent, that depends on what you believe how life was created. Did life come about by accident or do you believe that God created us? Some people believe life was created by the accidental combination of atoms that always existed... into life as we know it. No need then, for God in creation. That does not mean they are not good people. Most are good, even 2 though God is not a part of their lives. Atheism also, doesn’t guarantee good behavior anymore than religion does. I think the words of Katharine Hepburn, a great American actress sums up atheism for most people…”I’m an atheist and that’s it. I believe there’s nothing we can know except that we should be kind to each other and do what we can for other people.” For believes in a Creator, the words in John’s gospel ring true. John 1:3-4 “All things came to be through him, and without him nothing came to be. What came to be through him was life, and this life was the light of the human race.” For Christians we believe that God created us for a purpose. -

PACKAGE 2: Quito, the Andes & the Galapagos DAY 1: Saturday

DAY 1: Saturday Arrival to Quito: Quito’s “Mariscal Sucre“ International Airport (UIO) is one of the busiest airports in South America, and the best one in the region at the 2018 at the World Travel Awards. It’s located about 11 miles east of the city. Welcome to Quito: Quito is the capital and the largest city in Ecuador (population: 2.7M). At 9,350 ft. above sea level it’s the highest (constitutional) capital city in the world. Transfer from airport to our Airbnb or hotel: Our luxurious property is located in a safe, private, sought-after residential area of the capital, with some of the most incredible views of the city. A first-class hotel is the alternative. PACKAGE 2: DAY 2: Sunday Quito, The Andes Pululahua Crater (weather permitting): is & The Galapagos one of only two volcanic craters inhabited in the world, and the only one that is farmed. -Itinerary highlights- The land here is extremely fertile because it is volcanic soil. The caldera of this extinct volcano is approximately 3 miles wide, one of the largest volcanic craters in the planet. Temple of the Sun: Its structure resembles a castle, and is the home of a temple that reveres the Sun like Ecuadorian pre- Columbian indigenous did, and at the same time it’s a museum and art repository for the famous Ecuadorian artist that constructed and owns this complex. Intiñan Museum: This onsite museum located right on top or the Equator Line features interactive exhibits on how the Incas determined the middle of the Earth, plus interesting science experiments such as balancing an egg on a nail and the affects of the Coriolis force on earth. -

Ordo in Choro Servandus: Rules for the Choir In

ORDO IN CHORO SERVANDUS: RULES FOR THE CHOIR IN COLONIAL MÉXICO by Jorge Adan Torres, B.M.M.E. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music with a Major in Music August 2016 Committee Members: John C. Schmidt, Chair Kevin Mooney Ludim Pedroza COPYRIGHT by Jorge Adan Torres 2016 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Jorge Adan Torres, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a multitude of individuals who in one way or another are responsible for the completion of this work. First and foremost, I wish to thank the members of the Thesis Committee. Dr. Kevin Mooney, your persistent questioning of the importance of minuscule findings and how they affect this work—and the world at large—will always echo in the back of my mind. Dr. Ludim Pedroza, your suggestions in the early stages of this work led to a tremendous shift in how I approached and utilized sources. To my advisor and friend, Dr. John Schmidt, your incredible patience and interest in this work have been more than I could have ever asked. -

New Granada Circa 1750

z New Granada Circa 1750 [email protected] www.jaimeeguiguren.com 1 The Archangel Michael Defeating the Devil New Granada Circa 1750 Anonymous, Quito School 93 x 64 x 48 cm Provenance: Private collection, Spain [email protected] www.jaimeeguiguren.com 2 Materials: Pinewood, glass eyes, gold, silver, gilt copper, imitation emerald gemstones, fabric, glue and iron. Techniques used: Carved polychrome wood, gilded using “coquilla” brushed gold leaf technique, carnation, silver applied using silver gilding or “corladura” technique, glued fabric, silver filigree and thin sheets of gilt copper. [email protected] www.jaimeeguiguren.com 3 “Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought back. But he was not strong enough, and they lost their place in heaven. The great dragon was hurled down—that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray” (Revelation 12: 7) Full-length, free-standing sculpture depicting the Archangel Michael defeating the devil. Winged, standing and in a victorious pose, with his left leg bent at the knee, his right arm raised and brandishing a sword. His wings and plated doublet display varying tones of blue with gold leaf, and the sleeve of his left arm reaches the elbow, decorated with foliage motifs, also blue and gold leaf, on a base of gilt silver to attain a metallic sheen. The cuff of the sleeve is made up of a very thin plate of finely worked gilt copper, imitating lace or gold brocade. He wears a green sash across his chest over his armor and tight to his body, richly decorated with brushed gold leaf, in the form of foliage motifs. -

Methodology for the Conservation of Polychromed Wooden Altarpieces

METHODOLOGY FOR THE CONSERVATION OF POLYCHROMED WOODEN ALTARPIECES Consejería de Cultura Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico The Getty Conservation Institute Camino de los Descubrimientos s/n 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700 Isla de la Cartuja, 41092 Sevilla, España Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684, U.S.A. Tel (34) 955 037 000 Tel (1) 310 440 7325 Fax (34) 955 037 001 Fax (1) 310 440 7702 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/iaph http://www.getty.edu/conservation/ Román Fernández-Baca Casares Timothy P. Whalen Director Director Lorenzo Pérez del Campo Jeanne Marie Teutonico Jefe Centro de Intervención Associate Director, Programs en el Patrimonio Histórico Editor Françoise Descamps Assistant editor Jennifer Carballo Copy editor Kate Macdonald Translations Cris Bain-Borrego Alessandra Bonatti Graphic design Marcelo Martín Guglielmino Printer Escandon SA - Sevilla Cover Center Drawing of Ornamental Top, Alonso Cano. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photographs by Elke Walford, Hamburg (Copyright © Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY) Top left Main Altarpiece of Santos Juanes, Capilla Real de Granada, Spain. Photograph by José Manuel Santos, Madrid (Copyright © IAPH, Spain) Center left Main Altarpiece of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca, México. Photograph by Guillermo Aldana (Copyright © INAH, México) Bottom left Main Altarpiece of the Minor Basílica of San Francisco, La Paz, Bolivia. Photograph by Fernando Cuellar Otero Published by: Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Cultura The J. Paul Getty Trust © Junta de Andalucía. Consejería de Cultura The J. Paul Getty Trust ISBN Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material published in this book and to obtain Legal permission to publish. -

The Cathedral “Passionate, Erudite, Living Legend Lecturers

“Pure intellectual stimulation that can be popped into Topic Subtopic the [audio or video player] anytime.” History Medieval History —Harvard Magazine The Cathedral “Passionate, erudite, living legend lecturers. Academia’s best lecturers are being captured on tape.” —The Los Angeles Times The Cathedral “A serious force in American education.” Course Guidebook —The Wall Street Journal Professor William R. Cook State University of New York at Geneseo Professor William R. Cook has taught thousands of students over the course of more than 35 years at the State University of New York at Geneseo, where he is Distinguished Teaching Professor of History. Professor Cook is an expert in medieval history, the Renaissance and Reformation periods, and the Bible and Christian thought. The Medieval Academy of America awarded Professor Cook the CARA Award for Excellence in the Teaching of Medieval Studies for his achievements. THE GREAT COURSES® Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, VA 20151-2299 Guidebook USA Phone: 1-800-832-2412 www.thegreatcourses.com Cover Image: © Sites and Photos Photographer: Samuel Magal. Course No. 7868 © 2010 The Teaching Company. PB7868A PUBLISHED BY: THE GREAT COURSES Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfi elds Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 Phone: 1-800-832-2412 Fax: 703-378-3819 www.thegreatcourses.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2010 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. -

Download Download

A Major Confraternity Commission in Quito, Ecuador: the Church of El Sagrario^ SUSAN V. WEBSTER On 4 November 1694, members of the Confraternity of the Most Holy Sacrament gathered excitedly in the chapel of San Ildefonso in the Cathedral of Quito where they were to draw up and sign a contract with the architect who would build their new church. The signing of the contract marked a moment of great triumph for the confraternity, for it represented the culmination of decades of effort and planning, both financial and logistical. According to its terms, the confraternity engaged the architect to undertake "the design and construction of the Church of El Sagrario starting from its first foundations until it is finished and complete with the required offices of sacristies, crypts, and all other necessities for the service of the said Church." The signature of the architect, Jose Jaime Ortiz, along with those of the governing members of the confraternity and two representatives from the Cathedral Chapter, appears at the end of the document. The imposing colonial church of El Sagrario is one of the most well known historical monuments in Quito (fig. 1). Constructed along the south wall of the Cathedral, to which it is connected by an interior portal. El Sagrario serves as parish church for the lively Cathedral sector in the heart of colonial Quito. Despite its popular and historic status, until now almost nothing has been known of its origins, authorship, patronage, or process of construction. Even the dating of the church has been the subject