World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Sectorización Y Determinación De Oferta Hídrica Del Acuífero Del Río Bueno”

GOBIERNO DE CHILE MINISTERIO DE OBRAS PÚBLICAS DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE AGUAS DIVISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS Y PLANIFICACIÓN INFORME TÉCNICO “SECTORIZACIÓN Y DETERMINACIÓN DE OFERTA HÍDRICA DEL ACUÍFERO DEL RÍO BUENO” REALIZADO POR: División de Estudios y Planificación SDT Nº 417 Santiago, Diciembre 2018 ÍNDICE 1 INTRODUCCIÓN ................................................................................. 4 2 OBJETIVOS........................................................................................ 5 2.1 Objetivo general ........................................................................... 5 2.2 Objetivos específicos ..................................................................... 5 3 ANTECEDENTES DISPONIBLES ............................................................. 6 4 SECTORIZACIÓN DEL ACUÍFERO DEL VALLE DEL RÍO BUENO .................. 7 4.1 Identificación de la zona de estudio ................................................ 7 4.2 Metodología ................................................................................. 7 4.3 Resultados Obtenidos .................................................................... 9 4.4 Pluviometría y Fluviometría .......................................................... 10 4.5 Infiltración ................................................................................. 12 4.5.1 Umbral de Escorrentía (P0) .................................................... 12 4.5.2 Escorrentía e Infiltración ........................................................ 15 4.6 Caracterización hidrogeológica -

List of Acronyms

LIST OF ACRONYMS A______________________________ 20. ANARCICH: NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COMMUNITY RADIOS 1. AP: PACIFIC ALLIANCE. AND CITIZENS OF CHILE. 2. ATN: SOCIETY OF AUDIOVISUAL 21. ARCHITECTURE OF CHILE: DIRECTORS, SCRIPTWRITERS AND SECTORAL BRAND OF THE DRAMATURGS. ARCHITECTURE SECTOR IN CHILE. 3. ACHS: CHILEAN SECURITY B______________________________ ASSOCIATION. 22. BAFONA: NATIONAL FOLK BALLET. 4. APCT: ASSOCIATION OF PRODUCERS AND FILM AND 23. BID: INTER-AMERICAN TELEVISION. DEVELOPMENT BANK. 5. AOA: ASSOCIATION OF OFFICES OF 24. BAJ: BALMACEDA ARTE JOVEN. ARCHITECTS OF CHILE. 25. BIPS: INTEGRATED BANK OF 6. APEC: ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIC SOCIAL PROJECTS. COOPERATION FORUM. C______________________________ 7. AIC: ASSOCIATION OF ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS OF CHILE 26. CNTV: NATIONAL TELEVISION A.G. COUNCIL. 8. ACHAP: CHILEAN PUBLICITY 27. CHEC: CHILE CREATIVE ECONOMY. ASSOCIATION. 28. CPTPP: COMPREHENSIVE AND 9. ACTI: CHILEAN ASSOCIATION OF PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP. COMPANIES A.G. 29. CHILEACTORS: CORPORATION OF 10. ADOC: DOCUMENTARY ACTORS AND ACTRESSES OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 30. CORTECH: THEATER 11. ANIMACHI: CHILEAN ANIMATION CORPORATION OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION. 31. CRIN: CENTER FOR INTEGRATED 12. API CHILE: ASSOCIATION OF NATIONAL RECORDS. INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS OF CHILE. 32. UNESCO CONVENTION, 2005: 13. ADG: ASSOCIATION OF CONVENTION ON THE PROTECTION DIRECTORS AND SCRIPTWRITERS OF AND PROMOTION OF THE DIVERSITY CHILE. OF CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS. 14. ADTRES: GROUP OF DESIGNERS, 33. CNCA: NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TECHNICIANS AND SCENIC CULTURE AND ARTS. PRODUCERS. 34. CCHC: CHILEAN CHAMBER OF 15. APECH: ASSOCIATION OF CONSTRUCTION, A.G. PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS OF CHILE. 35. CCS: SANTIAGO CHAMBER OF 16. ANATEL: NATIONAL TELEVISION COMMERCE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 36. CORFO: PRODUCTION 17. ACA: ASSOCIATED DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION. -

Centro Latinoamericano De Demografia (Celade)

CENTRO LATINOAMERICANO DE DEMOGRAFIA (CELADE) DIVISIÓN POLÍTICO-ADMINISTRATIVA DEL PAÍS CHILE 1970 01 PROVINCIA DE TARAPACÁ 01 1 DEPARTAMENTO DE ARICA 01 1 01 Comuna Arica 01 1 01 01 Distrito Morro 01 1 01 02 Distrito Chinchorro 01 1 01 03 Distrito Chacalluta 01 1 01 04 Distrito Poconchile 01 1 01 05 Distrito Molinos 01 1 01 06 Distrito Livilcar 01 1 01 07 Distrito Azapa 01 1 01 08 Distrito Mercado 01 1 02 Comuna General Lagos 01 1 02 01 Distrito General Lagos 01 1 02 02 Distrito Cosapilla 01 1 03 Comuna Putre 01 1 03 01 Distrito Putre 01 1 03 02 Distrito Socoroma 01 1 03 03 Distrito Parinacota 01 1 04 Comuna Belén 01 1 04 01 Distrito Belén 01 1 04 02 Distrito Tignamar 01 1 04 03 Distrito Lauca 01 1 05 Comuna Codpa 01 1 05 01 Distrito Codpa 01 1 05 02 Distrito Esquiña 01 1 05 03 Distrito Caritaya 01 1 05 04 Distrito Camarones 01 1 05 05 Distrito Chaca 01 2 DEPARTAMENTO DE PISAGUA 01 2 01 Comuna Pisagua 01 2 01 01 Distrito Pisagua 01 2 01 02 Distrito Junin 01 2 01 03 Distrito Zapiga 01 2 01 04 Distrito Camiña 01 2 01 05 Distrito Tana 01 2 02 Comuna Negreiros 01 2 02 01 Distrito Negreiros 01 2 02 02 Distrito Santa Catalina 01 2 02 03 Distrito Isluga 01 2 02 04 Distrito Chiapa 01 2 02 05 Distrito Aroma 01 3 DEPARTAMENTO DE IQUIQUE 01 3 01 Comuna Iquique 01 3 01 01 Distrito Puerto 01 3 01 02 Distrito Condell 01 3 01 03 Distrito Guantajaya 01 3 01 04 Distrito Punta de Lobos 01 3 01 05 Distrito Cavancha 01 3 01 06 Distrito 21 de Mayo 01 3 01 07 Distrito Manuel Montt 01 3 01 08 Distrito Arturo Pratt 01 3 02 Comuna Huara 01 3 02 01 Distrito Huara -

Chapter 11 RAIL TRANSPORT in CHILE

Chapter 11 RAIL TRANSPORT IN CHILE Raimundo Soto 1 Extensive reform was completed in the rail sector in Chile and different models were used, including full privatisation and concessions. Both types of reforms achieved significant efficiency and welfare gains and reforms have improved the industry operations, particularly in freight. Motivation for the reforms was to reduce subsidies: that issue remains, particularly in the passenger sector. 11.1 INTRODUCTION Railways played a significant role in social life in Chile for almost a century. Between 1860 and 1950 railroads were an exemplar of modernisation, integration and economic development. By 1950, however, the industry had started to decline, unable to compete with more efficient means of transportation (buses and trucks). By the mid 1970s railroads were bankrupt, surviving through government subsidies. Two decades later, passenger services had almost disappeared (accounting for less than 1% of total traffic). Freight operations, on the contrary, had been privatised and revitalised, and concentrated on small profitable market niches usually in remote areas of the economy (Thompson & Angerstein 1997). This paper reviews the Chilean case and analyzes the current standing and operations of the industry, focusing on the reforms, public sector involvement, regulation, market entry, vertical integration, externalities and political factors. The Chilean economy underwent a massive restructuring in the mid 1970s. This included opening to foreign trade, complete market deregulation, inflation control, macroeconomic stabilisation and, most importantly for our study, a complete reallocation of government subsidies. In this economic turnaround, despite the waste and inefficiency associated with the publicly-owned railroad monopoly, no specific reforms were devised for railroads. -

Libro Camino Real ABRIL.Pdf

IndiceDE CONTENIDOS Prólogo 7 Introducción 8 Descripción geográfica de la zona 10 Primer Camino Real y despoblamiento 12 Reconstrucción del Camino Real 14 Época Contemporánea del Camino Real 20 El Camino Real en la actual comiuna de Los Muermos 21 Comuna de Fresia 30 Comuna de Frutillar 40 Comuna de Purranque 42 Comuna de Río Negro 57 Comuna de Osorno 70 Comuna de San Pablo 70 Epílogo 74 Perspectivas 76 Fuentes Utilizadas 77 ANEXO Catastro Patrimonial, Cultural y Natual 79 ANEXO Extensión Camino Real 124 Página 4 Página 5 Prólogo El Servicio Nacional de Turismo (SERNATUR) es un organismo público encargado de promover y difundir el desarrollo de la actividad turística de Chile. Su Misión Institucional es ejecutar una Política Nacional de Turismo mediante la implementación de planes y programas que incentiven la competitividad y participación del sector privado, el fomento de la oferta turística, la promoción y difusión de los destinos turísticos resguardando el desarrollo sustentable de la actividad, que beneficien a los visitantes, nacionales y extranjeros, prestadores de servicios turísticos, comunidades y al país en su conjunto. Como uno de nuestros objetivos es ‘fomentar y velar por el desarrollo integral de los territorios’ creemos que el libro “Memoria Viva del Camino Real región de Los Lagos” es una maravillosa oportunidad de acercarnos a personas extraordinarias, que a través de su testimonio, nos permiten soñar una ruta turística, donde su mayor valor, esta dado por el talento y trabajo de sus habitantes. A través de este libro se entregan los testimonios de decenas de familias que viven en torno al antiguo Camino Real construido por los conquistadores españoles y que a través de su trazado, entre los fuertes de Ancud y de Valdivia, muestran orgullosos la identidad cultural huilliche, española y chilota. -

Essal 06012017.Pdf

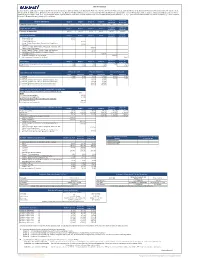

TARIFAS VIGENTES De acuerdo a lo establecido en los Decretos Nº 116 del 31 de agosto de 2011 del Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo; Nº 186 del 30 de junio de 2009 del Ministerior de Economía Fomento y Reconstrucción y Nº 120, del 15 de abril del 2014, del Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo; que fijan las fórmulas tarifarias de los servicios de producción y distribución de agua potable y recolección y disposición de aguas servidas para la Empresa de Servicios Sanitarios de Los Lagos ESSAL S.A., se informa las tarifas vigentes para los consumos a contar del 06/01/2017 a los clientes de los grupos tarifarios: 1, 2, 3 y 4; y los sectores denominados “A1 Sector Chinquihue” y “Loteo Lomas de Reloncaví” (Ex Sanitaria Sur), ambos de Puerto Montt. A1 Sector Lomas de CARGOS TARIFARIOS Grupo 1 Grupo 2 Grupo 3 Grupo 4 Chinquihue Reloncaví Cargo fijo clientela ($/mes) 716 716 716 716 707 726 A1 Sector Lomas de Cargos Variables ($/m3) Grupo 1 Grupo 2 Grupo 3 Alerce Chinquihue Reloncaví Consumo de agua potable 445,63 587,36 707,18 447,81 451,31 590,03 A1 Sector Lomas de Servicio de alcantarillado: Grupo 1 Grupo 2 Grupo 3 Alerce Chinquihue Reloncaví Osorno y Futrono 948,71 Castro y Dalcahue 812,68 La Unión y Río Bueno 967,31 Ancud, Frutillar, Puerto Montt, Puerto Varas-Llanquihue y 831,28 Futaleufú Lanco, Los Lagos, Máfil, Paillaco, Panguipulli, San José, San 1090,55 Pablo, Corral y Lago Ranco Achao, Calbuco, Chaitén, Chonchi, Fresia, Los Muermos, 954,52 Purranque-Corte Alto, Quellón, Río Negro y Maullín Localidad de Alerce 690,14 A1 Sector -

Plan Regulador Comunal De Purranque Región De Los Lagos

ILUSTRE MUNICIPALIDAD DE PURRANQUE PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE PURRANQUE REGIÓN DE LOS LAGOS EVALUACIÓN AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA INFORME AMBIENTAL ABRIL 2019 PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE PURRANQUE PROFESIONAL RESPONSABLE ……………………………………………………… Maximiliano Salazar Palomo, Ingeniero Civil Geógrafo Abril 2019 PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL DE PURRANQUE ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS 1. RESUMEN EJECUTIVO ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 2. ACERCA DEL PLAN REGULADOR COMUNAL .................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 OBJETIVOS DEL PLAN ........................................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1.1. Objetivo General ....................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.2. Objetivos de planificación .......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 JUSTIFICACIÓN DE LA FORMULACIÓN DEL PLAN .......................................................................... 2-2 2.3 OBJETO DE EVALUACIÓN .................................................................................................................. 2-2 2.4 ÁMBITO TEMPORAL Y TERRITORIAL DE APLICACIÓN ................................................................... 2-3 3. POLÍTICAS DE DESARROLLO SUSTENTABLE Y MEDIO AMBIENTE ............................................... -

RAIMUNDO SOTO Associate Professor Instituto De Economía Pontificia Universidad Católica De Chile

RAIMUNDO SOTO Associate Professor Instituto de Economía Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile EDUCATION 1996 Ph.D. in Economics, Georgetown University. 1986 Bachelor of Arts in Economics, Universidad de Chile. ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES TEACHING Universidad Católica de Chile: Econometric Theory (graduate), Time Series Analysis (graduate), Econometrics (undergraduate), and Macroeconomics (undergraduate). ILADES-Georgetown University: Econometrics (graduate), Advanced Econometrics (graduate), Industrial Organization (graduate), Advanced Macroeconomics (graduate), and Macroeconomic Theory (graduate). Universidad de Chile: Econometrics, Graduate School in Business and Economics. PUBLICATIONS AND RESEARCH PAPERS Edited Books The Economy of Dubai. Editor with A. Alfaris, Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN: 9780198758389. Economic Growth. Sources, Trends, and Cycles. Edited with N. Loayza, Banco Central de Chile: Santiago de Chile, 2002. Inflation Targeting: Design, Performance, Challenges. Edited with N. Loayza, Banco Central de Chile: Santiago de Chile, 2002 Desafíos para Chile en el Siglo XXI: Reformas Pendientes y Desarrollo Económico. Edited with C. Aedo, R. Bergoeing, H. Mena, and E. Saavedra. ILADES: Santiago de Chile, 1999. Exchange Rates and Economic Development in Africa. Edited with I. Elbadawi, Proceedings of the Bi-Annual AERC Research Workshop, special issue of the Journal of African Economics, (vol. 6, #3), Oxford University Press, 1997. La Industria Eléctrica en Chile, Aspectos Económicos. Edited with F. Morandé, R. Charún, and R. Raineri, ILADES: Santiago de Chile, 1996 Articles Published in Refereed Journals (* = ISI Journals) 1. Why Do Countries Have Fiscal Rules? (with I. Elbadawi and K.Schmidt-Hebbel), Economia Chilena, 18(3): 28-61, 2015. 2. Resource Rents, Institutions and Civil Wars (with I. Elbadawi), Defense and Peace Economics.*, 26(1): 89-113, 2014. -

The Role of the World Bank Group in The

Public Disclosure Authorized a. LU~~~~~~~~ I- .CT . h D LLJ c:12 cI~~~~~~~~~~~~~~L-~~~~~~~ r-in4 IT. - ~~ '4.3~~~~~~~igv) . .cl LU Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized I D E V E L O P M E N T I N P R A C T I C E Sustainable Transport Other Recent Development in Practice Books Improving Women's Health in India Sustainable Transport: Priorities for Policy Reform Priorities and Strategies in Education: A World Bank Review (also available in French and Spanish) Better Urban Services: Finding the Right Incentives (also available in French and Spanish) Strengthening the Effectiveness of Aid: Lessons for Donors Enriching Lives: Overcoming Vitamin and Mineral Malnutrition in Developing Countries (also available in French and Spanish) A New Agenda for Women's Health and Nutrition (also available in French) Population and Development: Implications for the World Bank East Asia's Trade and Investment: Regional and Global Gains from Liberalization Goverance: The World Bank's Experience Higher Education: The Lessons of Experience (also available in French and Spanish) Better Health in Africa: Experience and Lessons Learned (also available in French) Argentina's Privatization Program: Experience, Issues, and Lessons Sustaining Rapid Development in East Asia and the Pacific Sustainable Transport Priorities for Policy Reform T H E W O R L D B A N K W A S H I N G T O N, D. C. (C 1996 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America First printing May 1996 The Development in Practice series publishes reviews of the World Bank's activities in different regions and sectors. -

Ciudades, Pueblos, Aldeas Y Caseríos 2019

CIUDADES, PUEBLOS, ALDEAS Y CASERÍOS 2019 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICAS Marzo / 2019 PRESENTACIÓN El Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (INE) da a conocer en esta publicación la edición actualizada de “Ciudades, pueblos, aldeas y caseríos”, tomando como base la información del Censo de Población y de Vivienda, realizado el 19 de abril de 2017. Consciente de la importancia de la planificación regional, provincial y comunal, el INE aporta en este documento datos pertinentes sobre las ciudades, pueblos, aldeas, caseríos, seleccionando las variables esenciales que caracterizan su población y vivienda. Así, este texto entrega cifras actualizadas, datos de población desagregados por sexo, recuentos sobre viviendas particulares, superficie de ciudades y pueblos del país y recientes modificaciones. Esta publicación marca, además, un hito en las definiciones geográficas del INE, ya que en ella se presenta la nueva conceptualización de ciudad, en la que se consideran las características político- administrativas de la categorización. Los antecedentes aquí desplegados quedan a disposición de instituciones públicas y privadas, consultoras, estudiantes, profesionales y usuarios en general. 2 CONSIDERACIONES CONCEPTUALES División geográfica censal: El territorio comunal se divide en distritos, los que pueden ser urbanos, rurales o mixtos. A su vez, en el área urbana se reconocen zonas censales y en el área rural, localidades. Las zonas censales se componen de manzanas y las localidades, de entidades, las que también tienen sus propias categorías. Los límites censales los define el INE y se encuentran sostenidos y enmarcados en los límites de la división político-administrativa (DPA). Sin embargo, su trazado no reviste un carácter legal. División geográfica censal Fuente: elaboración propia. -

The Operator's Story Appendix: Santiago's Story

Railway and Transport Strategy Centre The Operator’s Story Appendix: Santiago’s Story © World Bank / Imperial College London Property of the World Bank and the RTSC at Imperial College London 1 The Operator’s Story: Notes from Santiago Case Study Interviews – February 2017 Purpose The purpose of this document is to provide a permanent record for the researchers of what was said by people interviewed for ‘The Operator’s Story’ in Santiago. These notes are based upon 11 meetings between 16th and 20th May 2016. This document will form an appendix to the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Although the findings have been arranged and structured by Imperial College London, they remain a collation of thoughts and statements from interviewees, and continue to be the opinions of those interviewed, rather than of Imperial College London or the World Bank. Prefacing the notes is a summary of Imperial College’s key findings based on comments made, which will be drawn out further in the final report for ‘The Operator’s Story’. Method This content is a collation in note form of views expressed in the interviews that were conducted for this study. Comments are not attributed to specific individuals, as agreed with the interviewees and Metro de Santiago. However, in some cases it is noted that a comment was made by an individual external not employed by Metro de Santiago (‘external commentator’), where it is appropriate to draw a distinction between views expressed by Metro de Santiago themselves and those expressed about their organisation. List -

Región De Los Lagos Queilén Quellón Futaleufú Chaitén

SAN PABLO SAN JUAN DE LA COSTA OSORNO PUYEHUE RÍO NEGRO PURRANQUE PUERTO OCTAY FRUTILLAR FRESIA LLANQUIHUE PUERTO VARAS LOS MUERMOS PUERTO MONTT CALBUCO MAULLÍN COCHAMÓ ANCUD Operación servicios de transporte gratuito QUEMCHI DALCAHUE PRIMARIAS PRESIDENCIALES CURACO DE HUALAIHUÉ CASTRO VÉLEZ QUINCHAO PUQUELDÓN CHONCHI REGIÓN DE LOS LAGOS QUEILÉN QUELLÓN FUTALEUFÚ CHAITÉN PALENA SERVICIOS GRATUITOS QUE OPERARÁN DURANTE LAS PRIMARIAS PRESIDENCIALES REGIÓN SERVICIO ESPECIAL ZONA AISLADA ZONA AISLADA TOTAL GENERAL ELECCIONES OTROS MODOS (ZAOM) TERRESTRE DE LOS LAGOS 316 61 97 474 SERVICIOS ESPECIALES ELECCIONES GRATUITOS HORARIO COMUNA ORIGEN - DESTINO HORARIO IDA RETORNO (LOCALIDADES) DOMINGO DOMINGO ANCUD CHACAO - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD RECTA CHACAO - CHACAO VIEJO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD COÑIMO - CHACAO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD PUNTA CHILEN - CHACAO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD LLANCO1 Y 2 - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD KM 25 - COIPOMO - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD DUHATAO - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD YUSTE - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD AGUAS BUENAS - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD PUNTRA ESTACIÓN - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD LINAO - CHACAO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD HUELDEN - CHACAO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD LINAO - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD LA TIZA - ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD TAIQUEMO-CHAQUIGUAL-ANCUD 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 ANCUD CAULIN LA CUMBRE - CHACAO 08:30;14:00 12:30;17:30 CALBUCO PUTENÍO - CALBUCO 08:30;10:30 13:00;16:00 CALBUCO EL