The Operator's Story Appendix: Santiago's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Acronyms

LIST OF ACRONYMS A______________________________ 20. ANARCICH: NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COMMUNITY RADIOS 1. AP: PACIFIC ALLIANCE. AND CITIZENS OF CHILE. 2. ATN: SOCIETY OF AUDIOVISUAL 21. ARCHITECTURE OF CHILE: DIRECTORS, SCRIPTWRITERS AND SECTORAL BRAND OF THE DRAMATURGS. ARCHITECTURE SECTOR IN CHILE. 3. ACHS: CHILEAN SECURITY B______________________________ ASSOCIATION. 22. BAFONA: NATIONAL FOLK BALLET. 4. APCT: ASSOCIATION OF PRODUCERS AND FILM AND 23. BID: INTER-AMERICAN TELEVISION. DEVELOPMENT BANK. 5. AOA: ASSOCIATION OF OFFICES OF 24. BAJ: BALMACEDA ARTE JOVEN. ARCHITECTS OF CHILE. 25. BIPS: INTEGRATED BANK OF 6. APEC: ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIC SOCIAL PROJECTS. COOPERATION FORUM. C______________________________ 7. AIC: ASSOCIATION OF ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS OF CHILE 26. CNTV: NATIONAL TELEVISION A.G. COUNCIL. 8. ACHAP: CHILEAN PUBLICITY 27. CHEC: CHILE CREATIVE ECONOMY. ASSOCIATION. 28. CPTPP: COMPREHENSIVE AND 9. ACTI: CHILEAN ASSOCIATION OF PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP. COMPANIES A.G. 29. CHILEACTORS: CORPORATION OF 10. ADOC: DOCUMENTARY ACTORS AND ACTRESSES OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 30. CORTECH: THEATER 11. ANIMACHI: CHILEAN ANIMATION CORPORATION OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION. 31. CRIN: CENTER FOR INTEGRATED 12. API CHILE: ASSOCIATION OF NATIONAL RECORDS. INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS OF CHILE. 32. UNESCO CONVENTION, 2005: 13. ADG: ASSOCIATION OF CONVENTION ON THE PROTECTION DIRECTORS AND SCRIPTWRITERS OF AND PROMOTION OF THE DIVERSITY CHILE. OF CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS. 14. ADTRES: GROUP OF DESIGNERS, 33. CNCA: NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TECHNICIANS AND SCENIC CULTURE AND ARTS. PRODUCERS. 34. CCHC: CHILEAN CHAMBER OF 15. APECH: ASSOCIATION OF CONSTRUCTION, A.G. PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS OF CHILE. 35. CCS: SANTIAGO CHAMBER OF 16. ANATEL: NATIONAL TELEVISION COMMERCE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 36. CORFO: PRODUCTION 17. ACA: ASSOCIATED DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION. -

CHAPTER 5 Transport and Air Quality in Santiago, Chile

CHAPTER 5 Transport and air quality in Santiago, Chile M. Osses1 & R. Fernández2 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Chile, Chile. 2Department of Civil Engineering, University of Chile, Chile. Abstract This chapter offers a review of the evolution of the transport system in Santiago de Chile during the period 2000–2010, and the implications of local transport policy on vehicle emissions and air quality. The chapter comprises five sections, starting with a general overview of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago and its population, as well as a description of the current transport system. The relationship between transport and air quality is analysed for the period 1991– 2001, describing car ownership and modal split trends, the technological evolution of vehicles, pollutant emissions from transport, and air quality trends. Finally, a critical review of Santiago’s transport policy is made, using the main programs of the 2001–2010 Urban Transport Plan for Santiago as a case study. The new public transport plan is included in this critical analysis (Transantiago), as well as a set of short-term strategies, road investment and car-use regulations, and non-motorized transport plans for pedestrians and cyclists in the city. Transport trends, however, show that Santiago is following the well-known car- public transport vicious circle that developed countries have gone through. This may offset the environmental effects from vehicle and transport improvements within the city. 1 Urban characteristics of Santiago The Metropolitan Region of Santiago, Chile, has a population of 6.1 million inhabitants, concentrating 40% of the whole population in the country. According to the latest census, the population of the Metropolitan Region of Santiago has grown by 15.3% during the last 10 years [1]. -

International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability 2020 Delegate Packet

International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability 2020 Delegate Packet Dear Delegate, Thank you for participating in the Sixteenth International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic & Social Sustainability. We are pleased you will be joining us in Santiago, Chile at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile & the University of Chile. We hope you are looking forward to coming together with colleagues and members of the On Sustainability Research Network this January. In preparation for the conference, we have put together some information that we hope will prove useful to you as you begin to prepare for the conference and your arrival in Santiago. In this document, you will find a variety of information on subjects, such as transportation, hotel and travel, activities and extras, conference registration, equipment, and session types. This packet is a starting point for your preparations, and we realize you may have some additional questions after reviewing the material here. For any questions that remain please visit the conference website at onsustainability.com/2020-conference. We hope your planning goes well, and we look forward to seeing you in Santiago! Page 2 Table of Contents Venue and Conference Information Conference Venue ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Registration Desk Hours and Location ................................................................................................................ -

UIT SUBTEL University of Chile 1

ITU Symposium and Workshop on small satellite regulation and communication systems Santiago de Chile, Chile, 7-9 November 2016 GENERAL INFORMATION A. THE EVENT 1. Focal Points: UIT SUBTEL University of Chile 1. (english) Yvon Henri 1. Luis Ramírez 1. Dr. Marcos Díaz Quezada Phone: +41 22 730 5536 Phome: +56 224 213 651 Phone: +56 9 90510540 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 2. (español) Sergio Scarabino 2. Ing. Alex Becerra Saavedra Phone: +56 979 670 968 Phone: +56 9 78126798 e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] 2. Venue Sitie: Enrique d’Etigny Lyon Auditorium, Beauchef Poniente Building, Physic Sciences and Mathematics Faculty, University of Chile Address: Avenida Beauchef 851, Santiago Centro, Santiago, Chile. Map External View of Enrique D’Etigny Auditorium - 1 - Enrique D’Etigny Auditorium (red circle) y sourrounding How to get there: METRO: The venue is 700-800 meters from the Metro stations Line L2 -Orange (see Metro map at the end of the document, and more detail in Section 3) - Parque O'higgins (when arriving in S-N sense) - Toesca (when arriving in N-S sense) BUS: Transantiago buses that pass near Auditorium Enrique D'Etigny are: 506, 506e, 507, 509, 510, 121 (see details in section 2) Accommodation and hotel reservations Event has not official hotels, and there are not hotels around the event site. It is suggested the nearest hotel zone in Comuma Providencia (4-5 km east from the venue) which has hotels of various categories and prices. -

Presentazione Standard Di Powerpoint

Italian Infrastructure Day 2014 Milan September 9, 2014 Index ■ Company at a Glance . Projects in execution ■ Highlights . Focus on revenues & profitability . New Orders & upcoming opportunities ■ Financials . NFP . Cash Flow ■ Main Events Italian Infrastructure Day 2014 2 Company at a Glance GROUP HIGHLIGHTS Workforce Pure player in heavy civil engineering and construction Construction Backlog by Geography as at June 2014 More than 31K employees Middle — Focused on large heavy civil engineering, where the group is among Asia & East 8% from 88 different the global leaders and is able to generate returns better than closest Oceania large European peers 4% nationalities. Italy Contract structures allow Global player present in over 40 countries with over 31,000 Africa 35% employees 28% flexible and dynamic LatAm approach to workforce — Approx. 67% of construction backlog outside of Italy North 13% Europe America 11% — Well balanced geographic presence between Developed Markets and 1% Emerging Markets Total: €29.2bn — Several untapped opportunities for geographic expansion where the Backlog 1H 2014 Revenues by Geography Group is today underrepresented (Australia, US) Highly diversified backlog Italy Large and well diversified backlog provides visibility on future 11% which has reached €29.2 results bn at June 2014, of which Highly experienced, pro-active management team focused on value €22 bn is Construction creation Backlog Rest of world — Proven track record in achieving targets 89% Total: €2,1bn Italian Infrastructure Day 2014 3 Projects in execution: worldwide experience, technical competence June 2014 Backlog Breakdown Riachuelo Construction Backlog by Geography By Segment Middle Concessions Asia & East 8% Oceania 25% 4% Italy Tocoma Dam Africa 35% 28% Construction 75% LatAm North 13% Europe America 11% 1% Total: €29.2bn Total: €29.2bn Tokwe Mukorsi Dam 19 Hydro & DAM projects in execution in 4 Continents Africa Asia Latin America North America . -

UBB Travel Information

TRAVEL INFORMATION FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Dirección General de Relaciones Internacionales - 2007 VISAS ¾ International students must apply for a Student Visa at the Chilean consulate in their home country once they have received a letter of admission from Universidad del Bío-Bío. To find the nearest Consular Office, check the following web site of the Chilean Ministry of External Relations: http://www.minrel.cl/pages/misiones/index.html. ¾ A Student Visa allows the holder to study at educational establishments recognized by the government of Chile. It is valid for one year and may be renewed. ¾ International students must register their visa with the Policia de Investigaciones-Extranjería, the Investigations Police and Immigration Office. Bring your passport, two photocopies of the page in your passport showing your personal information, two photocopies of the page containing your visa, and three passport-size (4 cm x 4 cm) color photos with your full name and passport number. You will be issued a “Certificado de Registro”, for which you will be charged a fee of 800 Chilean pesos. This document must then be presented to the “Servicio de Registro Civil” (Civil Registry); where you will be issued a Chilean Identification Card. The fee for the card is 3,200 Chilean pesos. Students who are staying in Chile less than 30 days do not need to register their visa. • Address and office hours of Policía de Investigaciones de Chile- Extranjería: In Concepción: Angol Nº 815, phone 56-41-2236124, office hours: from 9:00 to 12:30 and from 15:00 to 17:00 hrs. In Chillán: Vega de Saldías Nº 350, phone 56-42-237660, office hours: from 8:00 to 12:30 and from 15:00 to 17:00 hrs. -

Registration Document 2016/17

* TABLE OF CONTENTS REGISTRATION DOCUMENT 2016/17 DESCRIPTION CORPORATE 1 OF GROUP ACTIVITIES AFR 3 5 GOVERNANCE 137 Industry characteristics 4 Chairman’s report 138 Competitive position 7 Executive Committee AFR 181 Strategy 8 Statutory Auditors’ report prepared Offering 9 in accordance with Article L. 225‑235 of the French Commercial Code Research and development 15 on the report prepared by the Chairman of the Board of Alstom AFR 182 MANAGEMENT REPORT Interests of the officers 2 ON CONSOLIDATED and employees in the share capital 183 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – Related‑party agreements and commitments 190 AFR FISCAL YEAR 2016/17 AFR 19 Statutory Auditors 190 Main events of fiscal year 2016/17 20 Objectives for 2020 confirmed 21 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: Commercial performance 22 6 ALSTOM’S SOCIAL Orders backlog 24 RESPONSIBILITY 191 Income Statement 24 Sustainable development strategy 192 Free cash flow 26 Designing sustainable mobility solutions 200 Net Debt 27 Environmental performance 207 Equity 27 Social performance 215 Non‑GAAP financial indicators definitions 28 Relationships with external stakeholders 233 Synthesis of indicators/key figures 2016/17 244 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AFR 31 Report by one of the Statutory Auditors, 3 Consolidated income statement 32 appointed as an independent third party , on the consolidated environmental, Statutory financial statements 98 labour and social information presented in the management report 247 AFR RISK FACTORS 119 Table of compulsory CSR information AFR 250 4 Risks in relation to the economic environment -

Metro De Santiago WHERE the CITY MEETS

Metro de Santiago WHERE THE CITY MEETS www.metro.cl WHERE THE CITY MEETS Metro de Santiago Guaripola Guachaca Dióscoro Rojas recently described “the Metro is the most democratic and republican place we have in Santiago” this statement best describes the metro as a socio-economic melting pot that offers beyond a means of transportations to this great city. RESEARCH BY Joseph Philips 2 [ JULY 2019 ] BUSINESS EXCELLENCE BUSINESS EXCELLENCE [ JULY 2019 ] 3 METRO DE SANTIAGO hen Business Excellence first visited of lines 3 and 6, totalling 37 kilometres of beyond our 2013 article. It was first conceived Metro de Santiago, nearly 6 years ago track and 28 stations. Maintaining the same over 30 years ago but faced significant delays, W at the end of 2013, its management was standards across the extended and new lines “The highlight of the largely due to the 1985 earthquake that shook about to implement a plan for infrastructure would be a challenge - Metro de Santiago US$400 million investment Chile’s capital city. Its arrival is not only a improvements in the network. This was to system is renowned for its low waiting time valuable addition to the metro system - halving involve the purchase of new train carriages, the for passengers. We were looking forward was to be the construction the journey times for many commuters in the modernization of older trains (which were to to seeing how everything shaped out in the of lines 3 and 6, totalling city - but also, in some ways, symbolic: a sign be fitted with positioning systems, in-carriage intervening eight years. -

Chapter 11 RAIL TRANSPORT in CHILE

Chapter 11 RAIL TRANSPORT IN CHILE Raimundo Soto 1 Extensive reform was completed in the rail sector in Chile and different models were used, including full privatisation and concessions. Both types of reforms achieved significant efficiency and welfare gains and reforms have improved the industry operations, particularly in freight. Motivation for the reforms was to reduce subsidies: that issue remains, particularly in the passenger sector. 11.1 INTRODUCTION Railways played a significant role in social life in Chile for almost a century. Between 1860 and 1950 railroads were an exemplar of modernisation, integration and economic development. By 1950, however, the industry had started to decline, unable to compete with more efficient means of transportation (buses and trucks). By the mid 1970s railroads were bankrupt, surviving through government subsidies. Two decades later, passenger services had almost disappeared (accounting for less than 1% of total traffic). Freight operations, on the contrary, had been privatised and revitalised, and concentrated on small profitable market niches usually in remote areas of the economy (Thompson & Angerstein 1997). This paper reviews the Chilean case and analyzes the current standing and operations of the industry, focusing on the reforms, public sector involvement, regulation, market entry, vertical integration, externalities and political factors. The Chilean economy underwent a massive restructuring in the mid 1970s. This included opening to foreign trade, complete market deregulation, inflation control, macroeconomic stabilisation and, most importantly for our study, a complete reallocation of government subsidies. In this economic turnaround, despite the waste and inefficiency associated with the publicly-owned railroad monopoly, no specific reforms were devised for railroads. -

Dodam Bridge

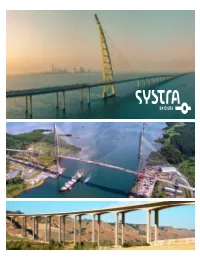

A GLOBAL BRIDGE World’s Longest Sea Bridge NETWORK SYSTRA has been a world leader in the World’s Longest Floating Bridge fi eld of transportation infrastructure for 60 years. Bridges are a major product SHEIKH JABER AL-AHMAD AL-SABAH CAUSEWAY line and a cornerstone of our technical Kuwait MONTREAL excellence in providing safe, effi cient, PARIS SEOUL and economical solutions. SAN DIEGO EVERGREEN POINT FLOATING BRIDGE World’s Longest Span International Bridge Technologies joined Seattle, Washington Railway Cable-Stayed Bridge NEW DELHI SYSTRA in 2017. The two companies DUBAI have combined their complementary World’s Longest technical expertise to offer specialized Concrete Span engineering services in all facets of bridge TIANXINGZHOU BRIDGE design, construction, and maintenance. China World’s Fastest Design & SYSTRA’s Global Bridge Network consists Construction Supervision on any Metro Project of over 350 bridge specialists deployed 3rd PANAMA CANAL CROSSING worldwide, with Bridge Design Centers Colón, Panama World’s Longest located in San Diego, Montreal, São Paolo, Double Suspension Bridge SÃO PAOLO Paris, Dubai, New Delhi, and Seoul. MECCA (MMMP) METRO Saudi Arabia CHACAO BRIDGE BRIDGE DESIGN CENTERS Chacao, Chile • SERVICES • Tender Preparation • BIM / BrIM • Conceptual Design • Complex Drafting & Specialized Detailing • Pre-Bid Engineering • Realistic Graphics • Proposal Preparation - 3D Renderings - Visual Animation • Specifications Preparation - Construction Sequence Animation • Bids Analysis • Technical Assistance During Construction -

RAIMUNDO SOTO Associate Professor Instituto De Economía Pontificia Universidad Católica De Chile

RAIMUNDO SOTO Associate Professor Instituto de Economía Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile EDUCATION 1996 Ph.D. in Economics, Georgetown University. 1986 Bachelor of Arts in Economics, Universidad de Chile. ACADEMIC ACTIVITIES TEACHING Universidad Católica de Chile: Econometric Theory (graduate), Time Series Analysis (graduate), Econometrics (undergraduate), and Macroeconomics (undergraduate). ILADES-Georgetown University: Econometrics (graduate), Advanced Econometrics (graduate), Industrial Organization (graduate), Advanced Macroeconomics (graduate), and Macroeconomic Theory (graduate). Universidad de Chile: Econometrics, Graduate School in Business and Economics. PUBLICATIONS AND RESEARCH PAPERS Edited Books The Economy of Dubai. Editor with A. Alfaris, Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN: 9780198758389. Economic Growth. Sources, Trends, and Cycles. Edited with N. Loayza, Banco Central de Chile: Santiago de Chile, 2002. Inflation Targeting: Design, Performance, Challenges. Edited with N. Loayza, Banco Central de Chile: Santiago de Chile, 2002 Desafíos para Chile en el Siglo XXI: Reformas Pendientes y Desarrollo Económico. Edited with C. Aedo, R. Bergoeing, H. Mena, and E. Saavedra. ILADES: Santiago de Chile, 1999. Exchange Rates and Economic Development in Africa. Edited with I. Elbadawi, Proceedings of the Bi-Annual AERC Research Workshop, special issue of the Journal of African Economics, (vol. 6, #3), Oxford University Press, 1997. La Industria Eléctrica en Chile, Aspectos Económicos. Edited with F. Morandé, R. Charún, and R. Raineri, ILADES: Santiago de Chile, 1996 Articles Published in Refereed Journals (* = ISI Journals) 1. Why Do Countries Have Fiscal Rules? (with I. Elbadawi and K.Schmidt-Hebbel), Economia Chilena, 18(3): 28-61, 2015. 2. Resource Rents, Institutions and Civil Wars (with I. Elbadawi), Defense and Peace Economics.*, 26(1): 89-113, 2014. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador