History of Quantum Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wave Nature of Matter: Made Easy (Lesson 3) Matter Behaving As a Wave? Ridiculous!

Wave Nature of Matter: Made Easy (Lesson 3) Matter behaving as a wave? Ridiculous! Compiled by Dr. SuchandraChatterjee Associate Professor Department of Chemistry Surendranath College Remember? I showed you earlier how Einstein (in 1905) showed that the photoelectric effect could be understood if light were thought of as a stream of particles (photons) with energy equal to hν. I got my Nobel prize for that. Louis de Broglie (in 1923) If light can behave both as a wave and a particle, I wonder if a particle can also behave as a wave? Louis de Broglie I’ll try messing around with some of Einstein’s formulae and see what I can come up with. I can imagine a photon of light. If it had a “mass” of mp, then its momentum would be given by p = mpc where c is the speed of light. Now Einstein has a lovely formula that he discovered linking mass with energy (E = mc2) and he also used Planck’s formula E = hf. What if I put them equal to each other? mc2 = hf mc2 = hf So for my photon 2 mp = hfhf/c/c So if p = mpc = hfhf/c/c p = mpc = hf/chf/c Now using the wave equation, c = fλ (f = c/λ) So mpc = hc /λc /λc= h/λ λ = hp So you’re saying that a particle of momentum p has a wavelength equal to Planck’s constant divided by p?! Yes! λ = h/p It will be known as the de Broglie wavelength of the particle Confirmation of de Broglie’s ideas De Broglie didn’t have to wait long for his idea to be shown to be correct. -

Famous Physicists Himansu Sekhar Fatesingh

Fun Quiz FAMOUS PHYSICISTS HIMANSU SEKHAR FATESINGH 1. The first woman to 6. He first succeeded in receive the Nobel Prize in producing the nuclear physics was chain reaction. a. Maria G. Mayer a. Otto Hahn b. Irene Curie b. Fritz Strassmann c. Marie Curie c. Robert Oppenheimer d. Lise Meitner d. Enrico Fermi 2. Who first suggested electron 7. The credit for discovering shells around the nucleus? electron microscope is often a. Ernest Rutherford attributed to b. Neils Bohr a. H. Germer c. Erwin Schrödinger b. Ernst Ruska d. Wolfgang Pauli c. George P. Thomson d. Clinton J. Davisson 8. The wave theory of light was 3. He first measured negative first proposed by charge on an electron. a. Christiaan Huygens a. J. J. Thomson b. Isaac Newton b. Clinton Davisson c. Hermann Helmholtz c. Louis de Broglie d. Augustin Fresnel d. Robert A. Millikan 9. He was the first scientist 4. The existence of quarks was to find proof of Einstein’s first suggested by theory of relativity a. Max Planck a. Edwin Hubble b. Sheldon Glasgow b. George Gamow c. Murray Gell-Mann c. S. Chandrasekhar d. Albert Einstein d. Arthur Eddington 10. The credit for development of the cyclotron 5. The phenomenon of goes to: superconductivity was a. Carl Anderson b. Donald Glaser discovered by c. Ernest O. Lawrence d. Charles Wilson a. Heike Kamerlingh Onnes b. Alex Muller c. Brian D. Josephson 11. Who first proposed the use of absolute scale d. John Bardeen of Temperature? a. Anders Celsius b. Lord Kelvin c. Rudolf Clausius d. -

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy And

The Development of Military Nuclear Strategy and Anglo-American Relations, 1939 – 1958 Submitted by: Geoffrey Charles Mallett Skinner to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, July 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature) ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 Abstract There was no special governmental partnership between Britain and America during the Second World War in atomic affairs. A recalibration is required that updates and amends the existing historiography in this respect. The wartime atomic relations of those countries were cooperative at the level of science and resources, but rarely that of the state. As soon as it became apparent that fission weaponry would be the main basis of future military power, America decided to gain exclusive control over the weapon. Britain could not replicate American resources and no assistance was offered to it by its conventional ally. America then created its own, closed, nuclear system and well before the 1946 Atomic Energy Act, the event which is typically seen by historians as the explanation of the fracturing of wartime atomic relations. Immediately after 1945 there was insufficient systemic force to create change in the consistent American policy of atomic monopoly. As fusion bombs introduced a new magnitude of risk, and as the nuclear world expanded and deepened, the systemic pressures grew. -

A Singing, Dancing Universe Jon Butterworth Enjoys a Celebration of Mathematics-Led Theoretical Physics

SPRING BOOKS COMMENT under physicist and Nobel laureate William to the intensely scrutinized narrative on the discovery “may turn out to be the greatest Henry Bragg, studying small mol ecules such double helix itself, he clarifies key issues. He development in the field of molecular genet- as tartaric acid. Moving to the University points out that the infamous conflict between ics in recent years”. And, on occasion, the of Leeds, UK, in 1928, Astbury probed the Wilkins and chemist Rosalind Franklin arose scope is too broad. The tragic figure of Nikolai structure of biological fibres such as hair. His from actions of John Randall, head of the Vavilov, the great Soviet plant geneticist of the colleague Florence Bell took the first X-ray biophysics unit at King’s College London. He early twentieth century who perished in the diffraction photographs of DNA, leading to implied to Franklin that she would take over Gulag, features prominently, but I am not sure the “pile of pennies” model (W. T. Astbury Wilkins’ work on DNA, yet gave Wilkins the how relevant his research is here. Yet pulling and F. O. Bell Nature 141, 747–748; 1938). impression she would be his assistant. Wilkins such figures into the limelight is partly what Her photos, plagued by technical limitations, conceded the DNA work to Franklin, and distinguishes Williams’s book from others. were fuzzy. But in 1951, Astbury’s lab pro- PhD student Raymond Gosling became her What of those others? Franklin Portugal duced a gem, by the rarely mentioned Elwyn assistant. It was Gosling who, under Franklin’s and Jack Cohen covered much the same Beighton. -

Physics Here at Uva from 1947-49

PHYS 202 Lecture 22 Professor Stephen Thornton April 18, 2005 Reading Quiz Which of the following is most correct? 1) Electrons act only as particles. 2) Electrons act only as waves. 3) Electrons act as particles sometimes and as waves other times. 4) It is not possible by any experiment to determine whether an electron acts as a particle or a wave. Answer: 3 In some cases we explain electron phenomena as a particle –for example, an electron hitting a TV screen. In other cases we explain it as a wave – in the case of a two slit diffraction experiment showing interference. Exam III Wednesday, April 20 Chapters 25-28 20 questions, bring single sheet of paper with anything written on it. Number of questions for each chapter will be proportional to lecture time spent on chapter. Last time Blackbody radiation Max Planck and his hypothesis Photoelectric effect Photons Photon momentum Compton effect Worked Exam 3 problems Today de Broglie wavelengths Particles have wavelike properties Wave-particle duality Heisenberg uncertainty principle Tunneling Models of atoms Emission spectra Work problems Finish last year’s exam problems de Broglie wavelength We saw that light, which we think of as a wave, can have particle properties. Can particles also have wavelike properties? A rule of nature says that if something is not forbidden, then it will probably happen. h λ = all objects p How can we demonstrate these wavelike properties? Typical wavelengths Tennis ball, m = 57 g, v = 60 mph; λ ~ 10-34 m. NOT POSSIBLE to detect!! 50 eV electron; λ ~ 0.2 x 10-9 m or 0.2 nm We need slits of the order of atomic dimensions. -

Nobel Prizes Social Network

Nobel prizes social network Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Maurice de Broglie Louis de Broglie (Phys.1929) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Henri Becquerel (Phys.1903) Pierre Curie (Phys.1903) = Marie Skłodowska Curie (Phys.1903, Chem.1911) Paul Langevin Maurice de Broglie Louis de Broglie (Phys.1929) Irène Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) = Frédéric Joliot-Curie (Chem.1935) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Clinton Davisson (Phys.1937) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. J. Thomson (Phys.1906) Owen Richardson (Phys.1928) Charlotte Richardson = Clinton Davisson (Phys.1937) Nobel prizes social network (more) Sir J. -

INDUSTRIAL STRENGTH by MICHAEL RIORDAN

THE INDUSTRIAL STRENGTH by MICHAEL RIORDAN ORE THAN A DECADE before J. J. Thomson discovered the elec- tron, Thomas Edison stumbled across a curious effect, patented Mit, and quickly forgot about it. Testing various carbon filaments for electric light bulbs in 1883, he noticed a tiny current trickling in a single di- rection across a partially evacuated tube into which he had inserted a metal plate. Two decades later, British entrepreneur John Ambrose Fleming applied this effect to invent the “oscillation valve,” or vacuum diode—a two-termi- nal device that converts alternating current into direct. In the early 1900s such rectifiers served as critical elements in radio receivers, converting radio waves into the direct current signals needed to drive earphones. In 1906 the American inventor Lee de Forest happened to insert another elec- trode into one of these valves. To his delight, he discovered he could influ- ence the current flowing through this contraption by changing the voltage on this third electrode. The first vacuum-tube amplifier, it served initially as an improved rectifier. De Forest promptly dubbed his triode the audion and ap- plied for a patent. Much of the rest of his life would be spent in forming a se- ries of shaky companies to exploit this invention—and in an endless series of legal disputes over the rights to its use. These pioneers of electronics understood only vaguely—if at all—that individual subatomic particles were streaming through their devices. For them, electricity was still the fluid (or fluids) that the classical electrodynamicists of the nineteenth century thought to be related to stresses and disturbances in the luminiferous æther. -

Iasinstitute for Advanced Study

IAInsti tSute for Advanced Study Faculty and Members 2012–2013 Contents Mission and History . 2 School of Historical Studies . 4 School of Mathematics . 21 School of Natural Sciences . 45 School of Social Science . 62 Program in Interdisciplinary Studies . 72 Director’s Visitors . 74 Artist-in-Residence Program . 75 Trustees and Officers of the Board and of the Corporation . 76 Administration . 78 Past Directors and Faculty . 80 Inde x . 81 Information contained herein is current as of September 24, 2012. Mission and History The Institute for Advanced Study is one of the world’s leading centers for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. The Institute exists to encourage and support fundamental research in the sciences and human - ities—the original, often speculative thinking that produces advances in knowledge that change the way we understand the world. It provides for the mentoring of scholars by Faculty, and it offers all who work there the freedom to undertake research that will make significant contributions in any of the broad range of fields in the sciences and humanities studied at the Institute. Y R Founded in 1930 by Louis Bamberger and his sister Caroline Bamberger O Fuld, the Institute was established through the vision of founding T S Director Abraham Flexner. Past Faculty have included Albert Einstein, I H who arrived in 1933 and remained at the Institute until his death in 1955, and other distinguished scientists and scholars such as Kurt Gödel, George F. D N Kennan, Erwin Panofsky, Homer A. Thompson, John von Neumann, and A Hermann Weyl. N O Abraham Flexner was succeeded as Director in 1939 by Frank Aydelotte, I S followed by J. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

• ISSN 0002-9920 March 2003 Volume 50, Number 3 Disks That Are Double Spiral Staircases page 327 The RieITlann Hypothesis page 341 San Francisco Meeting page 423 Primitive curve painting (see page 356) Education is no longer just about classrooms and labs. With the growing diversity and complexity of educational programs, you need a software system that lets you efficiently deliver effective learning tools to literally, the world. Maple® now offers you a choice to address the reality of today's mathematics education. Maple® 8 - the standard Perfect for students in mathematics, sciences, and engineering. Maple® 8 offers all the power, flexibility, and resources your technical students need to manage even the most complex mathematical concepts. MapleNET™ -- online education ,.u A complete standards-based solution for authoring, nv3a~ _r.~ .::..,-;.-:.- delivering, and managing interactive learning modules \~.:...br *'r¥'''' S\l!t"AaITI(!\pU;; ,"", <If through browsers. Derived from the legendary Maple® .Att~~ .. <:t~~::,/, engine, MapleNefM is the only comprehensive solution "f'I!hlislJer~l!'Ct"\ :5 -~~~~~:--r---, for distance education in mathematics. Give your institution and your students cornpetitive edge. For a FREE 3D-day Maple® 8 Trial CD for Windows®, or to register for a FREE MapleNefM Online Seminar call 1/800 R67.6583 or e-mail [email protected]. ADVANCING MATHEMATICS WWW.MAPLESOFT.COM I [email protected]\I I WWW.MAPLEAPPS.COM I NORTH AMERICAN SALES 1/800 267. 6583 © 2003 Woter1oo Ma')Ir~ Inc Maple IS (J y<?glsterc() crademork of Woterloo Maple he Mar)leNet so troc1ema'k of Woter1oc' fV'lop'e Inr PII other trcde,nork$ (ye property o~ their respective ('wners Generic Polynomials Constructive Aspects of the Inverse Galois Problem Christian U. -

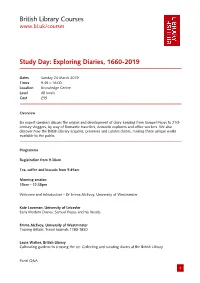

British Library Courses Study Day: Exploring Diaries, 1660-2019

British Library Courses www.bl.uk/courses Study Day: Exploring Diaries, 1660-2019 Dates Sunday 24 March 2019 Times 9.45 – 16:00 Location Knowledge Centre Level All levels Cost £55 Overview Six expert speakers discuss the origins and development of diary-keeping from Samuel Pepys to 21st- century vloggers, by way of Romantic travellers, Antarctic explorers and office workers. We also discover how the British Library acquires, preserves and curates diaries, making these unique works available to the public. Programme Registration from 9.30am Tea, coffee and biscuits from 9.45am Morning session 10am – 12.30pm Welcome and Introduction - Dr Emma McEvoy, University of Westminster Kate Loveman, University of Leicester Early Modern Diaries: Samuel Pepys and his friends Emma McEvoy, University of Westminster Touring Britain: Travel Journals 1780-1830 Laura Walker, British Library Cultivating gardens to crossing the ice: Collecting and curating diaries at the British Library Panel Q&A 1 12.30pm – 1.30pm LUNCH BREAK (lunch not provided) Afternoon session 1.30pm – 4pm Graham Farmelo, University of Cambridge Using diaries in writing scientific biographies Joe Moran, Liverpool John Moores University 20th-century diaries and the history of the everyday Clare Brant, King’s College London Diaries in the digital age Panel Q&A Tea and coffee 4pm Event ends Speakers Morning Kate Loveman is an Associate Professor in English 1600-1789 at the University of Leicester, working on the history of reading, sociability and information exchange. She is an expert on Samuel Pepys and recently edited a new annotated selection of his Diary (Everyman 2018). Her other publications include Samuel Pepys and his Books: Reading, Newsgathering, and Sociability 1660–1703 (2015), Reading Fictions 1660-1740: Deception in English Literary and Political Culture (2008) and work on the introduction of chocolate into England in the seventeenth century. -

Graham Farmelo: CV in Brief

Graham Farmelo: CV in brief Fellow of Churchill College, University of Cambridge E: [email protected], T: 07973 894926 2003–2018 Author and international consultant in public engagement • Author ‘The Universe Speaks in Numbers,’ to be published in UK and USA in May 2019 • Elected Fellow of Churchill College, University of Cambridge (2017) • Director’s visitor at the IAS, Princeton, every summer 2004-2018 • Chair, CERN History Forum’s on public dimensions of history, CERN, 1 February 2018 • Led series of art-science events involving Institute of Physics and national arts institutions: Royal Opera House (2014), Royal Shakespeare Company (2015) and Tate Modern (2015) • Organised public discussion between novelist Ian McEwan and physicists Nima Arkani-Hamed about the relationship between art and science – opening of ‘Collider’ exhibition at the Science Museum, 13 November 2014 • Writer-in-residence Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California at Santa Barbara (2015) and at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (2016) • Speaker at Blue Plaque event for Patrick Blackett’s residence in Chelsea, London, 10 April 2015 • Published ‘Churchill’s Bomb’ in US, Canada and UK (2013) • Awarded 2012 Kelvin Prize and Medal by the UK Institute of Physics • Chair, two International Panels for the Irish Government to review public provision for science communication and education in (2012, 2008) • Elected Honorary Fellow, British Science Association (2011) • Author of ‘The Strangest Man’, a biography of Paul Dirac (2009): winner, UK Costa Prize for Biography (2010), the Los Angeles Times Science Book Prize (2010); finalist for 2010 PEN biography in biography (New York); Physics World’s book of the 2009, one of Nature’s books of the year. -

(Owen Willans) Richardson

O. W. (Owen Willans) Richardson: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Richardson, O. W. (Owen Willans), 1879-1959 Title: O. W. (Owen Willans) Richardson Papers Dates: 1898-1958 (bulk 1920-1940) Extent: 112 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes (49.04 linear feet), 1 oversize folder (osf), 5 galley folders (gf) Abstract: The papers of Sir O. W. (Owen Willans) Richardson, the Nobel Prize-winning British physicist who pioneered the field of thermionics, contain research materials and drafts of his writings, correspondence, as well as letters and writings from numerous distinguished fellow scientists. Call Number: MS-3522 Language: Primarily English; some works and correspondence written in French, German, or Italian . Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics, which provided funds to support the processing and cataloging of this collection. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Additional The Richardson Papers were microfilmed and are available on 76 Physical Format reels. Each item has a unique identifying number (W-xxxx, L-xxxx, Available: R-xxxx, or M-xxxx) that corresponds to the microfilm. This number was recorded on the file folders housing the papers and can also be found on catalog slips present with each item. Acquisition: Purchase, 1961 (R43, R44) and Gift, 2005 Processed by: Tessa Klink and Joan Sibley, 2014 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Richardson, O. W. (Owen Willans), 1879-1959 MS-3522 2 Richardson, O. W. (Owen Willans), 1879-1959 MS-3522 Biographical Sketch The English physicist Owen Willans Richardson, who pioneered the field of thermionics, was also known for his work on photoelectricity, spectroscopy, ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, the electron theory, and quantum theory.