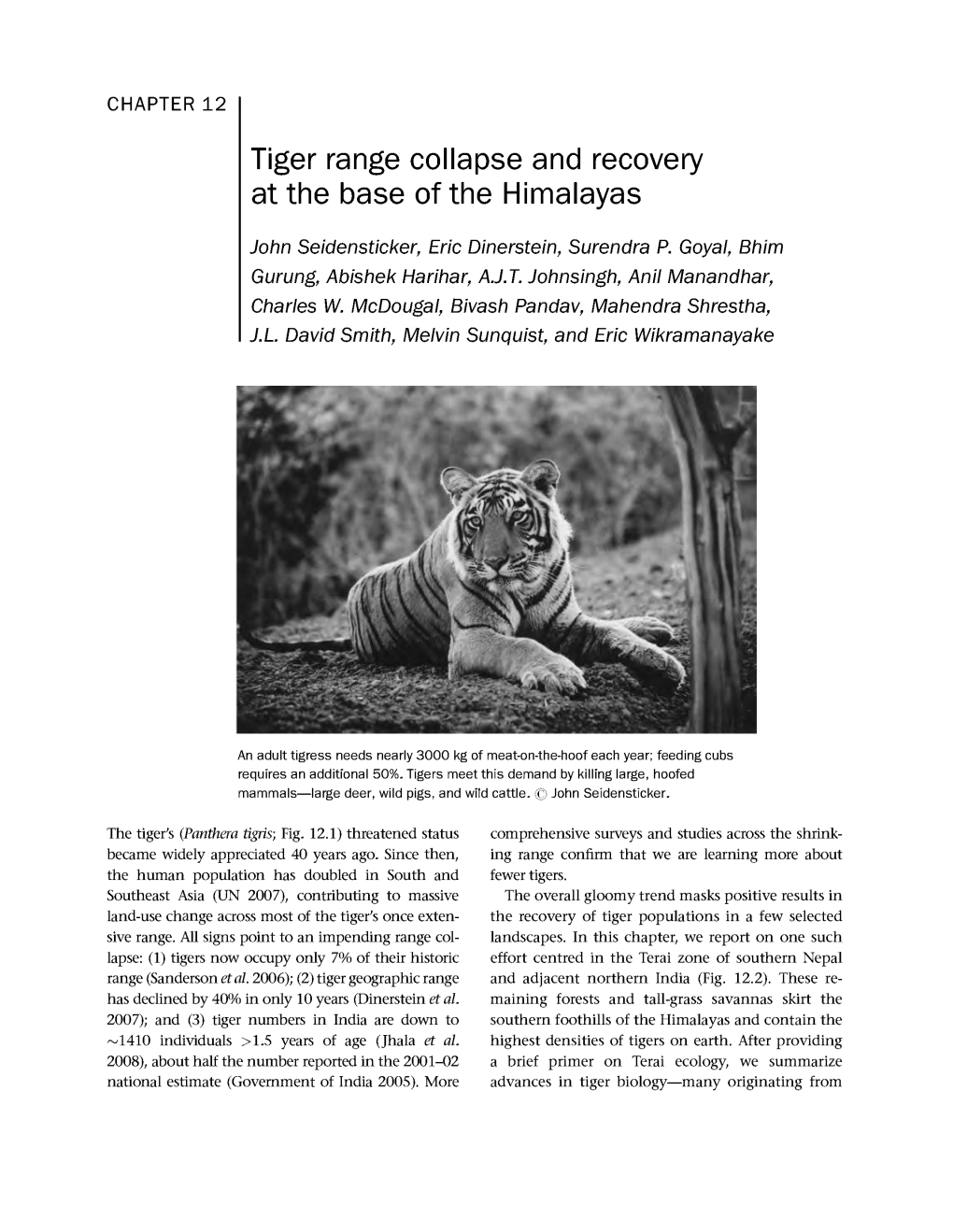

Tiger Range Collapse and Recovery at the Base of the Himalayas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts for Prelims (31St December 2018)

Important Facts for Prelims (31st December 2018) drishtiias.com/printpdf/important-facts-for-prelims-31st-december-2018 M-STrIPES There has been an increase in the number of poachers arrested by forest officials in past one year. The mobile app, M-STrIPES, used for surveillance and patrolling of tiger-populated areas has played a major role in this. M-STrIPES (Monitoring System For Tigers-Intensive Protection and Ecological Status) This app was developed by the National Tiger Conservation Authority and the Wildlife Institute of India in 2010. M-STrIPES allows patrol teams to keep a better tab on suspicious activity while also mapping the patrolling, location, routes and timings of forest officials. The App was also used in the All India-Tiger Estimation. Dudhwa Tiger Reserve The Dudhwa Tiger Reserve is a protected area in Uttar Pradesh that stretches mainly across the Lakhimpur Kheri and Bahraich districts. It comprises of the Dudhwa National Park, Kishanpur Wildlife Sanctuary and Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary. Dudhwa is home to a number of wildlife species, including the Bengal Tiger, Gangetic dolphin, rhinoceros, leopard, hispid hare, sambhar, swamp deer, hog deer, cheetah, sloth bear, elephant and over 450 species of birds. One District One Product (ODOP) Prime Minister of India recently attended a regional summit of ODOP scheme in Varanasi. ODOP Scheme was launched by the Uttar Pradesh Government to give a boost to traditional industries, synonymous with the respective state's districts. 1/2 Through this scheme, the state government wants to help local handicraft industries and products to gain national and international recognition through branding, marketing support, and easy credit. -

CP Vol VIII EIA

GOVERNMENT OF UTTAR PRADESH Public Works Department Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Part – A: Project Preparation DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume - VIII: Environmental Impact Assessment Report and Environmental Management Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) July 2015 India Consulting engineers pvt. ltd. Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP Report Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) Volume-VIII : Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIA) and Document Name Environmental Management Plan (EMP) (Detailed Project Report) Document Number EIRH1UP020/DPR/SH-93/GS/004/VIII Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Project Name Part – A: Project Preparation including Detailed Engineering Design and Contract Documentation Project Number EIRH1UP020 Document Authentication Name Designation Prepared by Dr. S.S. Deepak Environmental Specialist Reviewed by Sudhendra Kumar Karanam Sr. General Manager (Roads & Highways) Rajeev Kumar Gupta Deputy Team Leader Avadesh Singh Technical Head Approved by Rick Camise Team Leader History of Revisions Version Date Description of Change(s) Rev. 0 19/12/2014 First Submission Rev. 1 29/12/2014 Second Submission after incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 2 13/01/2015 Incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 3 16/07/2015 Revision after discussion with Independent Consultant Page i| Rev: R3 , Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP -

Land Tenures in Cooch Behar District, West Bengal: a Study of Kalmandasguri Village Ranjini Basu*

RESEARCH ARTICLE Land Tenures in Cooch Behar District, West Bengal: A Study of Kalmandasguri Village Ranjini Basu* Abstract: This paper describes and analyses changes in land tenure in Cooch Behar district, West Bengal. It does so by focussing on land holdings and tenures in one village, Kalmandasguri. The paper traces these changes from secondary historical material, oral accounts, and from village-level data gathered in Kalmandasguri in 2005 and 2010. Specifically, the paper studies the following four interrelated issues: (i) land tenure in the princely state of Cooch Behar; (ii) land tenure in pre-land-reform Kalmandasguri; (iii) the implementation and impact of land reform in Kalmandasguri; and (iv) the challenges ahead with respect to the land system in Kalmandasguri. The paper shows that an immediate, and dramatic, consequence of land reform was to establish a vastly more equitable landholding structure in Kalmandasguri. Keywords: Kalmandasguri, Cooch Behar, West Bengal, sharecropping, princely states, history of land tenure, land reform, village studies, land rights, panel study. Introduction This paper describes and analyses changes in land tenure in Cooch Behar district, West Bengal.1 It does so by focussing on land holdings and tenures in one village, Kalmandasguri.2 The paper traces these changes by drawing from secondary historical material, oral accounts, and from village-level data gathered in Kalmandasguri in 2005 and 2010. Peasant struggle against oppressive tenures has, of course, a long history in the areas that constitute the present state of West Bengal (Dasgupta 1984, Bakshi 2015). * Research Scholar, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, [email protected] 1 Cooch Behar is spelt in various ways. -

Geography of Early Historical Punjab

Geography of Early Historical Punjab Ardhendu Ray Chatra Ramai Pandit Mahavidyalaya Chatra, Bankura, West Bengal The present paper is an attempt to study the historical geography of Punjab. It surveys previous research, assesses the emerging new directions in historical geography of Punjab, and attempts to understand how archaeological data provides new insights in this field. Trade routes, urbanization, and interactions in early Punjab through material culture are accounted for as significant factors in the overall development of historical and geographical processes. Introduction It has aptly been remarked that for an intelligent study of the history of a country, a thorough knowledge of its geography is crucial. Richard Hakluyt exclaimed long ago that “geography and chronology are the sun and moon, the right eye and left eye of all history.”1 The evolution of Indian history and culture cannot be rightly understood without a proper appreciation of the geographical factors involved. Ancient Indian historical geography begins with the writings of topographical identifications of sites mentioned in the literature and inscriptions. These were works on geographical issues starting from first quarter of the nineteenth century. In order to get a clear understanding of the subject matter, now we are studying them in different categories of historical geography based on text, inscriptions etc., and also regional geography, cultural geography and so on. Historical Background The region is enclosed between the Himalayas in the north and the Rajputana desert in the south, and its rich alluvial plain is composed of silt deposited by the 2 JSPS 24:1&2 rivers Sutlej, Beas, Ravi, Chenab and Jhelum. -

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.2331(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.2331(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 10 | JUly - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ECOTOURISM AESTHETICS AND PROSPECTS: A GEOSPATIAL ASSESSMENT OF RAJAJI NATIONAL PARK Shairy Chaudhary1, M. S. Negi2 and Atul Kumar3 1&3Ph.D. Research Scholar, Associate Professor2 Department of Geography, H.N.B. Garhwal University (A Central University), Srinagar Garhwal, Uttarakhand, India. ABSTRACT There are 32 National parks, 92 Wild life sanctuaries located in 11 Himalayan states of India. Uttarakhand is the northern Himalayan state of India, where 6 National parks and 6 wild life sanctuaries established by the national and international organizations. These sites are well preserved, most beautiful attractions nationally and internationally among the tourists community for their amusement, knowledge and awareness regarding conservation of natural heritage. Rajaji National Park is one of the famous for his natural beauty, the prosperous diversity of flora, fauna and topographic landscape, which is located between Latitude 29° 56 ’ 40” N to 30° 20’ N and Longitude790 80’ E to 780 01’ 15” E in Pauri, Haridwar and Dehradun districts. It occupies around 820 Km2 areas in 9 forest ranges and situated in the lower Shiwalik range, foothills and Gangetic plains. Terrain relief of the park ranges between 271 m to 1381 m. from mean sea level. Shiwalik range passes from east to west from the park and River Ganga flows from North South and cut Shiwalik range in North East part of the park and makes flood plain in Southern part of Park. In the present study various aspects of the park such as topography, vegetative cover and Species, fauna species, Climate, accommodation facilities, transport and tourist attractions have been described using Remote Sensing and GIS geospatial tools and techniques. -

Making Way: Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor to Protect

OCCASIONAL REPORT NO. 10 MAKING WAY Till recent past the elephant population of Chilla on the east bank of the Ganga and Motichur, on the west, was one with regular movement between these two forest ranges of Rajaji National Park. Securing the Chilla-Motichur Corridor This movement, at one point, came to a virual halt because of to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park manmade obstacles like the Chilla power channel, an Army ammunition dump and rehabilitation of Tehri dam evacuees. The Eds: Vivek Menon, PS Easa and AJT Johnsingh problem was compounded by accidents owing to the railway track that passes through the area as National highway (NH 72). This study looks at WTI’s initiative in both securing the corridor as well as eliminating rail-hit incidents. B-13, Second floor, Sector - 6, NOIDA - 201 301 Uttar Pradesh, India Tel: +91 120 4143900 (30 lines) Fax: +91 120 4143933 Email: [email protected], Website: www.wti.org.in Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), is a non-profit conservation organisation, committed to help conserve nature, especially endangered species and threatened habitats, in partnership with communities and governments. Its vision is the natural heritage of India is secure. Project Team Suggested Citation: Menon, V; Easa,P.S; Johnsingh, A.J.T (2010) ‘Making Ashok Kumar Way’ - Securing the Chilla-Motichur corridor to protect elephants of Rajaji National Park. Wildlife Trust of India, New Delhi. Vivek Menon Aniruddha Mookerjee Keywords: Encroachment, Degradation, Sand mining, Corridor, Khand Gaon, P.S Easa Rehabilitation, Rajaji National Park, Anil Kumar Singh The designations of geographical entities in this publication and the A J T Johnsingh presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the authors or WTI concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries Editorial Team All rights reserved. -

Challenges and Opportunities of Transboundary Rhino Conservation

Challenges and opportunities of transboundary rhino conservation Challenges and opportunities of transboundary rhino conservation in India and Nepal Bibhab Kumar Talukdar1,2* and Satya Priya Sinha3 1Aaranyak and 2International Rhino Foundation C/o 50 Samanwoy Path (Survey), PO Beltola, Guwahati – 781 028, Assam, India; *Corresponding author email: [email protected] 3Wildlife Institute of India, Chandrabani, Dehradun, Uttarkhand – 248 001, India; email: [email protected] Abstract Currently, the wild population of the greater one-horned rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) is found in India and Nepal. To manage this transboundary population along the Indo-Nepal border, their habitats and numbers need scientific monitoring. Regular data should be collected on their movement patterns and management, and the data shared across borders with concerned conservation and management agencies to monitor the rhino population and the corridors they use, especially in Suklaphanta–Lagga Bagga, Pilibhit Forest Division, Dudhwa, Katerniaghat and Bardia landscape. Rhinos moving around the Indo-Nepal border in Katerniaghat– Bardia and Lagga Bagga–Suklaphanta should be fixed with radio collars to generate vital information that will assist conservation and management of the greater one-horned rhino along the border, strengthen transboundary planning and conservation for the rhino, besides orienting the police and border security forces in both countries to contribute towards protection of this rhino population moving between the countries. Résumé Actuellement, -

IYB-2010 and Countdown 2010 Celebration a Brief Activity Report

IYB-2010 and Countdown 2010 Celebration A Brief Activity Report By Santosh Kumar Sahoo, Ph.D. Chairman Conservation Himalayas 977/2, Sector 41-A, Chandigarh, U.T.India Tel.: +91 90 23 36 51 04 / +91 17 23 02 73 28 Email: [email protected] The Uttarakhand region of the northwestern Himalayas in India has a rich biodiversity all across its landscapes, particularly in its terai-bhabar region in its southern edge. The wildlife biodiversity in the terai-bhabar belt of Uttarakhand is found in Corbett National Park and the Rajaji National Park as well as all across its landscapes from the Asan barrage conservation reserve at Kalsi in the extreme west up to Sharda river in the extreme east bordering with western Nepal. Poaching, forest fire and wildlife body part trade continue to remain as serious threats to the wildlife in the Uttarakhand region. Illegal poaching of leopards and prey animals occurs in the tiger range areas of Uttarakhand state raising the level of threats to the endangered tiger (Panthera tigri tigris) population in its terai-bhabar tiger range areas. In the recent years, the human population in the fringe villages along the terai-bhabar belt in Uttarakhand shows signs of increase coupled with illiteracy and poverty, and their dependency on the local natural resources in the form of cattle grazing, fuel wood and fodder collection is on the rise. Threats to the tiger population are on rise as some of the recent tiger deaths particularly in the buffer zone areas of the reserve forests in the terai tiger habitats have reportedly been found to have links with poaching and tiger body part trade related activities (tiger skins, bones confiscated in village Fatehpur at Haldwani under the Ramnagar Forest Division. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

Rajaji National Park

A BRIEF PRESENTATION ON RAJAJI NATIONAL PARK By – S.P. Subudhi I.F.S Director, Rajaji National Park, Uttarakhand, Dehradun Location Map of Rajaji National Park INTRODUCTION Rajaji National Park – Area 820.42 sqkm. spread over in Dehradun, Haridwar and Pauri Garhwal districts of Uttarakhand. Three sanctuaries namely Rajaji, Motichur, Chilla and some Reserve Forest areas were amalgmated into a large protected area and named Rajaji National Park in the year 1983 after the famous freedom fighter and last Governor General Late Shri C. Rajgopalachari, popularly known as Rajaji. Biodiversity values 1. A magnificent ecosystem nestling in the Himalayan foot hills and beginning of the Vast Indo-Gangetic plains. 2. The P.A. represents several distinct zones and forest types, like riverine forests, broad leaf mixed forests, chirpine forests, scrubland and grassy pasture land. 3. It possess as many as 23 species of mammals and 315 avifauna species. 4. North Western most habitat of Asian Elephant and Tiger in Asia. 6. Rajaji is home of Asian Elephants and Indian Tiger. Flagship species- Asian Elephant Other Species- Tiger Leopard Hyena H. Black Bear Sloth Bear Ghural Deer Spp. Wild boar Tiger King Cobra Spotted Deers Leopard Census Figures of 2007/2008 Species M F C/J Total Elephant 95 212 111 418 Tiger 09 12 03 24 Leopard 95 106 19 220 Sambar 947 1791 518 3256 FLORA OF RAJAJI NATIONAL PARK • The forest ecosystem of the Rajaji N.P. are quite varied and diverse. • Sal (Shorea robusta) is the characteristic dominant trees species. • Other forests are mixed forests (T.belerica, Mallotus, B.ceiba etc.), Riverene forests, (S. -

View and Print the Publication

Forest Fire Prediction Modeling in the Terai Arc Landscape of the Lesser Himalayas Using the Maximum Entropy Method Amit Kumar Verma and Namitha Nhandadiyil Kaliyathan, Forest Research Institute, Dehradun, India; Narendra Singh Bisht, Arunachal Pradesh Forest Department, India; and Satinder Dev Sharma and Raman Nautiyal, Indian Council of Forestry Research & Education, Dehradun, India Abstract—The Terai Arc Landscape (TAL) is an ecologically important region of the Indian subcontinent, where anthropogenic habitat loss and forest fragmentation are major issues. The most prominent threat is forest fires because of their impacts on the microhabitat and macrohabitat characteristics and the resulting disruption of ecological processes. Moreover, wildfire aggravates conflicts between humans and wildlife in the forest fringe areas. The lack of a proper forest fire monitoring system in the TAL is a major management issue that needs attention for long-term forest viability. Hence, the present study was undertaken using maximum entropy modeling to predict the areas across the TAL at risk of wildfire and to identify key variables associated with fire occurrence. Spatiotemporally independent fire incidence locations along with other environmental variables were used to build the model. The accuracy of the model was assessed using the area under the curve. To evaluate the importance of each variable, a jackknife procedure was adopted. Areas in the projected map were categorized into high fire, marginal fire, and no fire areas. An adaptive forest management strategy can be implemented in the modeled high fire areas to mitigate forest fire and wildlife conflict in the TAL. Keywords: forest fire, maximum entropy, Terai Arc Landscape, Tiger INTRODUCTION biodiversity (Dennis and Meijaard 2001) because of changes in climate and in human use and misuse of A forest fire, whether caused by natural forces or fire.