Challenges and Opportunities of Transboundary Rhino Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Facts for Prelims (31St December 2018)

Important Facts for Prelims (31st December 2018) drishtiias.com/printpdf/important-facts-for-prelims-31st-december-2018 M-STrIPES There has been an increase in the number of poachers arrested by forest officials in past one year. The mobile app, M-STrIPES, used for surveillance and patrolling of tiger-populated areas has played a major role in this. M-STrIPES (Monitoring System For Tigers-Intensive Protection and Ecological Status) This app was developed by the National Tiger Conservation Authority and the Wildlife Institute of India in 2010. M-STrIPES allows patrol teams to keep a better tab on suspicious activity while also mapping the patrolling, location, routes and timings of forest officials. The App was also used in the All India-Tiger Estimation. Dudhwa Tiger Reserve The Dudhwa Tiger Reserve is a protected area in Uttar Pradesh that stretches mainly across the Lakhimpur Kheri and Bahraich districts. It comprises of the Dudhwa National Park, Kishanpur Wildlife Sanctuary and Katerniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary. Dudhwa is home to a number of wildlife species, including the Bengal Tiger, Gangetic dolphin, rhinoceros, leopard, hispid hare, sambhar, swamp deer, hog deer, cheetah, sloth bear, elephant and over 450 species of birds. One District One Product (ODOP) Prime Minister of India recently attended a regional summit of ODOP scheme in Varanasi. ODOP Scheme was launched by the Uttar Pradesh Government to give a boost to traditional industries, synonymous with the respective state's districts. 1/2 Through this scheme, the state government wants to help local handicraft industries and products to gain national and international recognition through branding, marketing support, and easy credit. -

CP Vol VIII EIA

GOVERNMENT OF UTTAR PRADESH Public Works Department Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Part – A: Project Preparation DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume - VIII: Environmental Impact Assessment Report and Environmental Management Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) July 2015 India Consulting engineers pvt. ltd. Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP Report Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) Volume-VIII : Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIA) and Document Name Environmental Management Plan (EMP) (Detailed Project Report) Document Number EIRH1UP020/DPR/SH-93/GS/004/VIII Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Project Name Part – A: Project Preparation including Detailed Engineering Design and Contract Documentation Project Number EIRH1UP020 Document Authentication Name Designation Prepared by Dr. S.S. Deepak Environmental Specialist Reviewed by Sudhendra Kumar Karanam Sr. General Manager (Roads & Highways) Rajeev Kumar Gupta Deputy Team Leader Avadesh Singh Technical Head Approved by Rick Camise Team Leader History of Revisions Version Date Description of Change(s) Rev. 0 19/12/2014 First Submission Rev. 1 29/12/2014 Second Submission after incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 2 13/01/2015 Incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 3 16/07/2015 Revision after discussion with Independent Consultant Page i| Rev: R3 , Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP -

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

Protected Areas in News

Protected Areas in News National Parks in News ................................................................Shoolpaneswar................................ (Dhum- khal)................................ Wildlife Sanctuary .................................... 3 ................................................................... 11 About ................................................................................................Point ................................Calimere Wildlife Sanctuary................................ ...................................... 3 ......................................................................................... 11 Kudremukh National Park ................................................................Tiger Reserves................................ in News................................ ....................................................................... 3 ................................................................... 13 Nagarhole National Park ................................................................About................................ ......................................................................................................................................... 3 .................................................................... 14 Rajaji National Park ................................................................................................Pakke tiger reserve................................................................................. 3 ............................................................................... -

Conservation, Conflict, and Community Context: Insights from Indian Tiger Reserves

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations December 2019 Conservation, Conflict, and Community Context: Insights from Indian Tiger Reserves Devyani Singh Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Singh, Devyani, "Conservation, Conflict, and Community Context: Insights from Indian Tiger Reserves" (2019). All Dissertations. 2534. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/2534 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSERVATION, CONFLICT, AND COMMUNITY CONTEXT: INSIGHTS FROM INDIAN TIGER RESERVES A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management by Devyani Singh December 2019 Accepted by: Dr. Robert B. Powell, Committee Chair Dr. Lincoln R. Larson, Co-Chair Dr. Lawrence Allen Dr. Brett Wright ABSTRACT Protected areas across the world have been established to preserve landscapes and conserve biodiversity. However, they also are crucial resources for nearby human populations who depend on them for subsistence and to fulfill social, economic, religious, and cultural needs. The contrasting ideologies of park use and conservation among diverse stakeholders (e.g. managers and local communities) make protected areas spaces of conflict. This mixed-methods study aimed to gain a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of these complex conflicts and potential solutions by focusing on the social and ecological landscapes surrounding two Indian protected areas: Dudhwa National Park (DNP in Uttar Pradesh) and Ranthambore National Park (RNP, in Rajasthan). -

Dudhwa, Katarniaghat

Dudhwa, Katarniaghat Those two Indian reserves are situated in Uttar Pradesh state on the border with Nepal. In the paste they were connected each to other and constituted part of so called Western Terai Landscape Complex. That reach and diverse environment has been heavily logged and settled both in India and Nepal in last forty years. As a result very few forest are now left outside the reserves. Fortunately both Indian sanctuaries are still connected with Nepali national parks of Suklapantha (Dudhwa) and Bardia (Katarniaghat). Maintaining corridors between those protected areas is crucial for their survival and constitute one of the main goals of the WWF Terai landscape project. The status of Dudhwa and Katarniaghat is different as first is gazetted as national park and tiger reserve whilst the later is listed as wildlife reserve. The gazettment of Katarniaghat as tiger reserve and national park is one of the steps that Indian authorities should undertake quickly in order to save the place. The next step could be the creation of the large transnational ‘peace park’ connecting two reserves in India (Dudhwa, Katarniaghat) and two in Nepal (Bardia and Suklapanta). Both Indian reserves are under constant pressure from growing rural population and poaching. Forest are being encroached and grazed by feral and domestic cattle. Firewood is being collected by local population. Many cars and trains pass daily trough sanctuaries. Environmental authorities as well as several NGO’s are struggling to close railroads crosscutting Katarniaghat and Dudhwa which are blamed to bring poachers and wood collectors deep inside the forest as well as killing wildlife. -

Handicraft Training for Tribal Group of Dudhwa, up CEE North As Part Of

Handicraft Training for Tribal group of Training on Climate Change, Disaster Dudhwa, UP Risk Reduction programme in Kashmir CEE North as part of its sustainable livelihood interventions organized a three- month basic level training programme on making of carpets, wall hangings and other handicraft items for Tharu community of Dudhwa Tiger Reserve.Tharu community is a tribe listed in the scheduled tribe category. The tribe is residing on the fringe of the protected area and have dependency on the forest resources for food, fodder and fuel. The participants included Zonal and Cluster Resource persons, responsible for Teachers' capacity building in their zones, SSA Coordinator of Idgah zone and Headmasters/Headmistresses form 44 schools As a part of capacity building for Climate Change Education and Disaster Risk The programme was inaugurated on Reduction in Kashmir, two trainings for the 19th October by Hon'ble Member of Trainers and Teachers from Idgah and Parliament Shri Jafar Ali Naqvi at Nishat Education zones of Srinagar district village Goubraula, Lakhimpur Kheri. were held from 13-16 December. In addition to climate change and disaster risk reduction modules, the participants also CEE North is working in the selected learned about 'Paryavaran Mitra' (PM) cluster of villages focusing on natural programme. resource management and sustainable livelihood interventions which aims at Paryavaran Mitra activities minimizing the dependency of the tribe from the forest resource and to enhance Paryavaran Mitra at Kankaria Carnival their skills for income generation. Various 2010, Ahmedabad Gujarat interventions related to alternative energy options, improvement in farming methods The weeklong Kankaria Carnival 2010 and livestock management linked with other kicked off in Ahmedabad on the 25 th of livelihood options. -

Carbon Finance: Solution for Mitigating Human–Wildlife Conflict in and Around Critical Tiger Habitats of India

POLICY BRIEF CARBON FINANCE: SOLUTION FOR MITIGATING HUMAN–WILDLIFE CONFLICT IN AND AROUND CRITICAL TIGER HABITATS OF INDIA Author Yatish Lele Dr J V Sharma Reviewers Dr Rajesh Gopal Dr S P Yadav Sanjay Pathak CARBON FINANCE: SOLUTION FOR MITIGATING HUMAN–WILDLIFE CONFLICT IN AND AROUND CRITICAL TIGER HABITATS OF INDIA i © COPYRIGHT The material in this publication is copyrighted. Content from this discussion paper may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided it is attributed to the source. Enquiries concerning reproduction should be sent to the address: The Energy and Resources Institute, Darbari Seth Block, India Habitat Centre, Lodhi Road, New Delhi – 110 003, India Author Yatish Lele, Associate Fellow, Forestry and Biodiversity Division, TERI Dr J V Sharma, Director, Forestry and Biodiversity Division, TERI Reviewers Dr Rajesh Gopal, Secretary General, Global Tiger Forum Dr S P Yadav, Member Secretary, Central Zoo Authority and Former DIG, National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) Sanjay Pathak, Director, Dudhwa Tiger Reserve, Uttar Pradesh Forest Department Cover Photo Credits Yatish Lele ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This policy brief is part of the project ‘Conservation of Protected Areas through Carbon Finance: Implementing a Pilot Project for Dudhwa Tiger Reserve’ under Framework Agreement between the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), referred to in short as the Norwegian Framework Agreement (NFA). We would like to thank the Norwegian MFA and Uttar Pradesh Forest Department for their support. SUGGESTED FORMAT FOR CITATION Lele, Yatish and Sharma, J V 2019. Carbon Finance: Solution for Mitigating Human–wildlife Conflict in and Around Critical Tiger Habitats of India, TERI Policy Brief. -

Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Bhadhi – Churella Taal Sector of Dudhwa National Park

Creation of a Viable Breeding Satellite Population of Great Indian One-Horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros Unicornis) in Bhadhi – Churella Taal sector of Dudhwa National Park View of Bhadhi Taal area – Proposed additional Rhino Area inside DNP/TR Dr. S.P Sinha, Consultant, HNO.IV C/O Wildlife Institute of India Chandrabani, Dehradun Uttarakhand (Member, IUCN’S Reintroduction Specialist Group & Rhino Specialist Group) & Prof Bitapi. C.Sinha, Scientist SF, Wildlife Institute of India Chandrabani Dehradun, Uttarakhand 1. BACKGROUND The Great Indian One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) was once widely distributed from Hindukush Mountain Range (Pakistan) to Myanmar and also all along the flood plains of Ganges River. In the last 200 years over-hunting, fragmentation of habitat by clearing forest for cultivation, desperate land use for agriculture, extension of tea gardens, reclamation of grasslands and swamps for fulfilling the basic needs of expanding livestock and human population and uncontrolled fires are the major causes of elimination of Indian Rhinoceros from most of its former range of distribution. The last Rhino in Uttar Pradesh was shot in the Pilibhit district adjacent to the Dudhwa National Park in 1878. At present the Indian Rhinoceros population of around 2855 is restricted to protected areas in Assam, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and Nepal. The Kaziranga National Park in Assam has 2048 Rhinos and the Royal Chitwan NP in Nepal has 408(2010). By considering the highly restricted distribution with poaching pressure, habitat specificity and considering the scattered small population, it becomes imperative to re-introduce the species in suitable habitats in its former range of distribution as one of the measures to be adopted for the long-term survival of this species. -

Pilibhit Tiger Reserve

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Pilibhit Tiger Reserve Conservation Opportunities and Challenges PRANAV CHANCHANI Vol. 50, Issue No. 20, 16 May, 2015 Pranav Chanchani ([email protected]) is a PhD candidate in ecology at Colorado State University, United States, and was a research associate at WWF-India between 2011 and 2013. Home to a sizeable tiger population and several other endangered species, the Pilibhit Forest Division, an erstwhile timber yielding reserve forest, was notified as a tiger reserve by the Uttar Pradesh state government in 2014. To successfully protect and perpetuate the tiger species in this area, noted for its "exemplary wildlife values", the administrators will have to preempt discord that is likely to arise between the forest department and human communities whose livelihoods are affected by the creation of the new reserve. In June 2014, the Government of Uttar Pradesh (UP) notified Pilibhit Forest Division (PFD) as a tiger reserve. Pilibhit Tiger Reserve (PTR) is noteworthy because it supports a notably large tiger population even though it has been an important timber yielding reserve forest for over 100 years. This situation, which is unique to PTR, raises a series of questions. What factors have enabled the persistence of tigers in the erstwhile PFD? How will its conversion into a tiger reserve benefit the species’ long term conservation in this region? And what must administrators and managers do to conserve this endangered species while also accommodating the needs of human communities dependent on forest resources? ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Map of Pilibhit Forest Division (Tiger Reserve) showing the locations of productive grassland habitats, forest-edge habitats, and the locations of key wildlife corridors. -

1 UTTAR PRADESH: Changing Perspectives

Knowledge Partner UTTAR PRADESH: Changing Perspectives 1 Title Uttar Pradesh: Changing Perspectives Author MRSS India Date February 2016 Copyright No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form by photo, photo-print, microfilm or any other means without written permission of FICCI and MRSS India Disclaimer The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty expressed is made to their accuracy, completeness or correctness. This document is for information purpose only. The information contained in this document is published for the assistance of the recipient but is not to be relied upon as authoritative or taken in substitution for the exercise of judgment by any recipient. This document is not intended to be a substitute for professional, technical or legal advice. All opinions expressed in this document are subject to change without notice. Neither MRSS India and FICCI, nor other legal entities in the group to which they belong, accept any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss however arising from any use of this document or its contents or otherwise arising in connection herewith. Many of the conclusions and inferences are specific inferences made by MRSS India in their expert capacity specifically in tourism sector and does not have any correlation with financing related outlook that as a research organization may have. Contact FICCI Majestic Research Services and Address Headquarters Solutions -

Project Document for the Purposes of CEO Endorsement Only

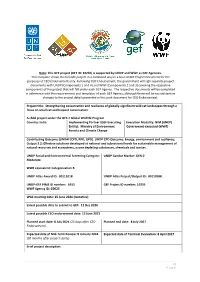

Note: This GEF project (GEF ID: 10235) is supported by UNDP and WWF as GEF Agencies. This template shows the full GEF project in a combined way in a base UNDP Project Document for the purposes of CEO Endorsement only. Following CEO Endorsement, the government will sign separate project documents with UNDP (Components 1 and 4) and WWF (Components 2 and 3) covering the respective components of the project that will fall under each GEF Agency. The respective documents will be completed in adherence with the requirements and templates of each GEF Agency, although there will be no substantive changes to the project detail presented in this joint document for CEO Endorsement. Project title: Strengthening conservation and resilience of globally-significant wild cat landscapes through a focus on small cat and leopard conservation A child project under the GEF-7 Global Wildlife Program Country: India Implementing Partner (GEF Executing Execution Modality: NIM (UNDP) Entity): Ministry of Environment Government-executed (WWF) Forests and Climate Change Contributing Outcome (UNDAF/CPD, RPD, GPD): UNDP CPD Outcome: Energy, environment and resilience; Output 3.2: Effective solutions developed at national and subnational levels for sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems, ozone depleting substances, chemicals and wastes. UNDP Social and Environmental Screening Category: UNDP Gender Marker: GEN-2 Moderate WWF equivalent: Categorization B UNDP Atlas Award ID: 00111018 UNDP Atlas Project/Output ID: 00110188 UNDP-GEF PIMS ID number: 6355