Did the November Elections Change Anything?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PES Report of Activities 2001-2004 (24 April 2004)

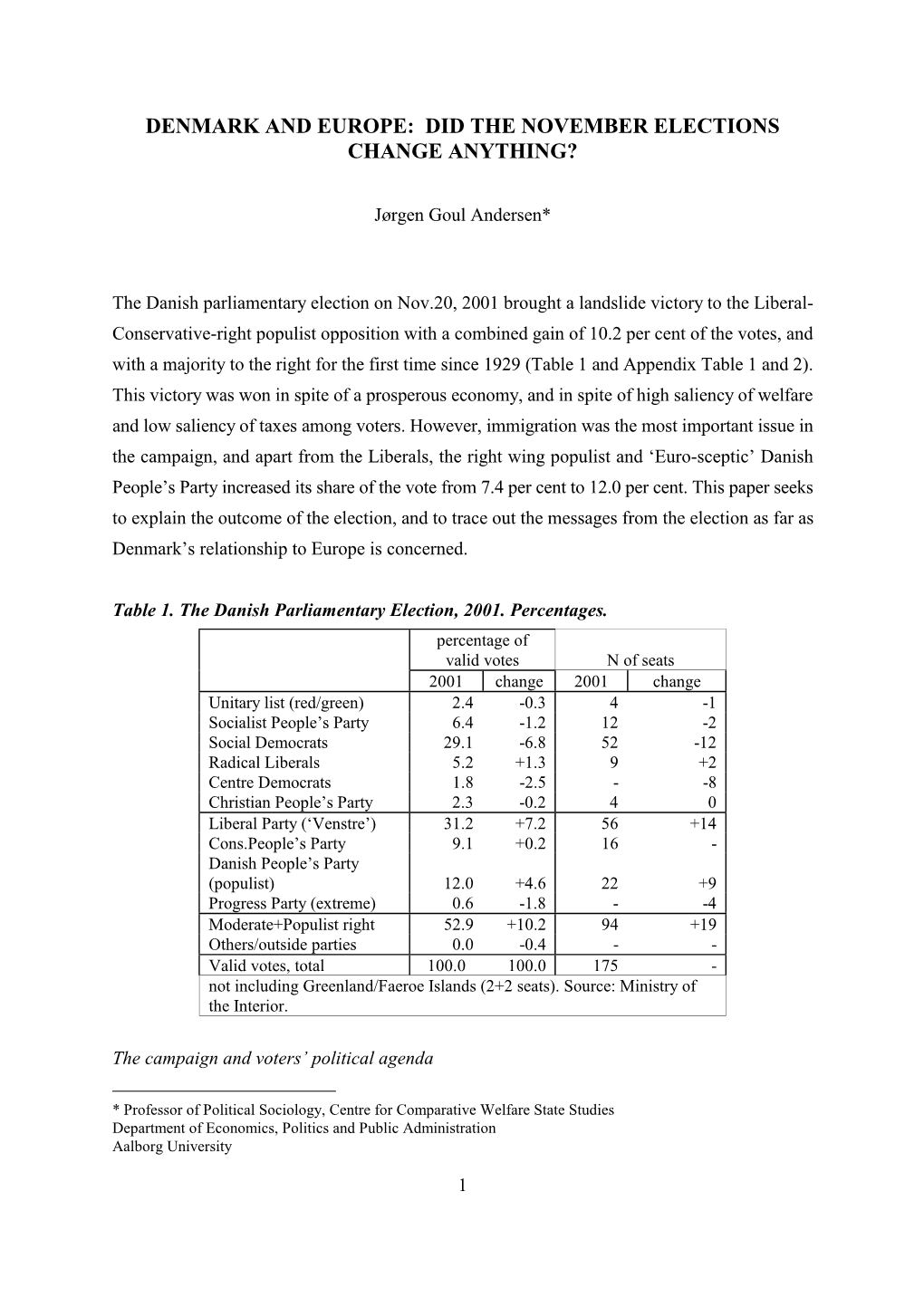

PES • PSE • SPE European Parliament rue Wiertz B 1047 Brussels PES report of activities 2001-2004 (24 April 2004) Introduction During the period between the 2001 Berlin Congress and 2004 Brussels Congress the Party of European Socialists has faced challenges both in political and organisational terms. After a period of extraordinary electoral success in the second half of the nineties, governmental participation of PES parties has gone down. Within the EU PES parties are in government in 6 out of 15 Member states, in the new Member States PES parties are in 5 out of 10 governments. There is however no reason to conclude that European Social Democracy is facing an electoral crisis. The vast majority of EU citizens from May 1 st onwards are governed at national level led by a PES party (Germany, United Kingdom, Sweden, Spain, Poland, Czech republic, Hungary and Lithuania) or by a government with PES party participation (Belgium, Finland and Slovenia.). Fact remains that during the period 2001-2004, President Robin Cook and the Presidency had to adapt the activities to the fact that less than before PES parties were governmental parties. The role of PES ministerial co-operation has decreased and more than before the PES has undertaken major policy co- ordination projects of its own. Two major policy co-ordination projects The co-ordination of the Social Democrat and Socialist members of the European Convention under the leadership of Giuliano Amato and later the globalisation project under the leadership of Poul Nyrup Rasmussen have been project of a magnitude and an impact the PES has never seen before. -

Liberal Vision Lite: Your Mid-Monthly Update of News from Liberal International

Liberal Vision Lite: your mid-monthly update of news from Liberal International Thu, Apr 15, 2021 at 6:59 PM Issue n°5 - 15 April 2021 SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER "We have a chance to re-think & re-invent our future", LI President El Haité tells Liberal Party of Canada Convention. In an introductory keynote, President of Liberal International, Dr Hakima el Haité, addressed thousands of liberals at the Liberal Party of Canada‘s largest policy convention in history. WATCH VIDEO CGLI’s Axworthy tells Canadian liberals, "To solve interlinked challenges, common threads must be found." On 9 April, as thousands of Candian liberals joined the Liberal Party of Canada's first-ever virtual National Convention, distinguished liberal speakers: Hon. Lloyd Axworthy, Hon. Diana Whalen, Chaviva Hosek, Rob Oliphant & President of the Canadian Group of LI Hon. Art Eggleton discussed liberal challenges and offered solutions needed for the decade ahead. WATCH VIDEO On World Health Day, Council of Liberal Presidents call for more equitable access to COVID vaccines Meeting virtually on Tuesday 7 April, the Council of Liberal Presidents convened by the President of Liberal International, Dr Hakima el Haité, applauded the speed with which vaccines have been developed to combat COVID19 but expressed growing concern that the rollout has until now been so unequal around the world. READ JOINT STATEMENT LI-CALD Statement: We cannot allow this conviction to mark the end of Hong Kong LI and the Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats released a joint statement on the conviction of LI individual member & LI Prize for Freedom laureate, Martin Lee along with other pro-democracy leaders in Hong Kong, which has sent shockwaves around the world. -

Flexicurity – an Open Method of Coordination at the National Level ? Jean-Claude Barbier, Fabrice Colomb, Per Kongshøj Madsen

Flexicurity – an open method of coordination at the national level ? Jean-Claude Barbier, Fabrice Colomb, Per Kongshøj Madsen To cite this version: Jean-Claude Barbier, Fabrice Colomb, Per Kongshøj Madsen. Flexicurity – an open method of coor- dination at the national level ?. 2009. halshs-00407394 HAL Id: halshs-00407394 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00407394 Submitted on 28 Jul 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Documents de Travail du Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Flexicurity – an open method of coordination, at the national level ? Jean-Claude BARBIER, Fabrice COLOMB, Per KongshØj MADSEN 2009.46 Maison des Sciences Économiques, 106-112 boulevard de L'Hôpital, 75647 Paris Cedex 13 http://ces.univ-paris1.fr/cesdp/CES-docs.htm ISSN : 1955-611X Flexicurity – an open method of coordination, at the national level? Jean-Claude Barbier Fabrice Colomb CNRS Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne Centre d’économie de la Sorbonne (CES) 106/112 Bd de l’Hôpital 75647 Paris Cedex 13, France Per Kongshøj Madsen Centre for Labour Market Research (CARMA) Aalborg University Fibigerstræde 1, DK-9220 Aalborg Ø., Denmark Document de Travail du Centre d'Economie1 de la Sorbonne - 2009.46 Résumé La flexicurité (ou flexisécurité) est une notion qui s’est répandue depuis le début des années 2000, à la suite de l’usage du terme aux Pays-Bas et au Danemark. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Growth of the Radical Right in Nordic Countries: Observations from the Past 20 Years

THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE PAST 20 YEARS By Anders Widfeldt TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: Observations from the Past 20 Years By Anders Widfeldt June 2018 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned for the eighteenth plenary meeting of the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), held in Stockholm in November 2017. The meeting’s theme was “The Future of Migration Policy in a Volatile Political Landscape,” and this report was one of several that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: the Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso- American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2018 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Layout: Sara Staedicke, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

PAPPA – Parties and Policies in Parliaments

PAPPA Parties and Policies in Parliament Version 1.0 (August 2004) Data description Martin Ejnar Hansen, Robert Klemmensen and Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard Political Science Publications No. 3/2004 Name: PAPPA: Parties and Policies in Parliaments, version 1.0 (August 2004) Authors: Martin Ejnar Hansen, Robert Klemmensen & Peter Kurrild- Klitgaard. Contents: All legislation passed in the Danish Folketing, 1945-2003. Availability: The dataset is at present not generally available to the public. Academics should please contact one of the authors with a request for data stating purpose and scope; it will then be determined whether or not the data can be released at present, or the requested results will be provided. Data will be made available on a website and through Dansk Data Arkiv (DDA) when the authors have finished their work with the data. Citation: Hansen, Martin Ejnar, Robert Klemmensen and Peter Kurrild- Klitgaard (2004): PAPPA: Parties and Policies in Parliaments, version 1.0, Odense: Department of Political Science and Public Management, University of Southern Denmark. Variables The total number of variables in the dataset is 186. The following variables have all been coded on the basis of the Folketingets Årbog (the parliamentary hansard) and (to a smaller degree) the parliamentary website (www.ft.dk): nr The number given in the parliamentary hansard (Folketingets Årbog), or (in recent years) the law number. sam The legislative session. eu Whether or not the particular piece of legislation was EU/EEC initiated. change Whether or not the particular piece of legislation was a change of already existing legislation. vedt Whether the particular piece of legislation was passed or not. -

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign Friday, 26 August It was Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s plan to introduce a bonus to people purchasing a house. This bonus has been criticized for artificially inflating house prices and therefore for being a bad way to instigate growth. On Saturday 20 August the Social Democrats (S) somehow learned about the plan and decided to launch it themselves, despite Helle Thorning-Schmidt having said on Friday that she did not want to introduce measures to stimulate the housing market. This led to a chaotic Saturday where Løkke Rasmussen and the Liberal Party (V) tried to do damage control. Quickly the Danish People’s Party (DF) declared their opposition to the plan due to a lot of their voters not being house owners. Liberal Alliance (LA) is as a general rule opposed to state subsidies so they were opposed as well leaving V and the Conservative Party (K) alone with the plan on the blue wing. On the red wing the situation was similar. S and the Socialist People’s Party (SF) agreed on the idea while the Unity List (EL) represents the left wing and therefore does not believe in the state funding those with the means to buy a house – plus a lot of their voters rent their homes. The Social Liberal Party (R) is opposed with the argument that the plan is a shortsighted one which will probably not do much for the economy anyway. Thus S-SF and VK were alone and they did not want to cooperate to get a majority for the plan. -

DENMARK Dates of Elections: 8 September 1987 10 May 1988

DENMARK Dates of Elections: 8 September 1987 10 May 1988 Purpose of Elections 8 September 1987: Elections were held for all the seats in Parliament following premature dissolution of this body on 18 August 1987. Since general elections had previously been held in January 1984, they would not normally have been due until January 1988. 10 May 1988: Elections were held for all the seats in Parliament following premature dissolution of this body in April 1988. Characteristics of Parliament The unicameral Parliament of Denmark, the Folketing, is composed of 179 members elected for 4 years. Of this total, 2 are elected in the Faeroe Islands and 2 in Greenland. Electoral System The right to vote in a Folketing election is held by every Danish citizen of at least 18 years of age whose permanent residence is in Denmark, provided that he has not been declared insane. Electoral registers are compiled on the basis of the Central Register of Persons (com puterized) and revised continuously. Voting is not compulsory. Any qualified elector is eligible for membership of Parliament unless he has been convic ted "of an act which in the eyes of the public makes him unworthy of being a member of the Folketing". Any elector can contest an election if his nomination is supported by at least 25 electors of his constituency. No monetary deposit is required. Each candidate must declare whether he will stand for a certain party or as an independent. For electoral purposes, metropolitan Denmark (excluding Greenland and the Faeroe Islands) is divided into three areas - Greater Copenhagen, Jutland and the Islands. -

Factsheet: the Danish Folketinget

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Danish Folketinget 1. At a glance Denmark is a Constitutional Monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. The Folketinget is a unicameral Parliament composed of 179 Members. The two self-governing regions, Greenland and the Faeroe Islands, each elect two Members. Of the other 175 Members, 135 are elected from ten multi-Member constituencies on a party list, proportional representation system using the d'Hondt method. The remaining 40 seats are allocated to ensure proportionality at a national level. Elections of the Folketinget must take place every four years, unless the Monarch, on the advice of the Prime Minister, calls for early elections. The general election on 5 June 2019 gave the "Red Bloc" a parliamentary majority in support of Social Democrats leader Mette Frederiksen as Prime Minister. The coalition comprises the Social Democrats, the Social Liberals, Socialist People's Party, the Red– Green Alliance, the Faroese Social Democratic Party and the Greenlandic Siumut, and won 93 of the 179 seats. The Government, announced on 27 June, is a single-party government. 2. Composition Results of the Folketinget elections on 5 June 2019 Party EP affiliation % Seats Socialdemokraterne (Social Democrats) 25,9% 48 Venstre, Danmarks Liberale Parti) (V) (Liberals) 23,45% 43 Dansk Folkeparti (DF) (Danish People's Party) 8,7% 16 Det Radikale Venstre (Danish Social Liberal Party) 8,6% 16 Socialistisk Folkeparti (SF) (Socialist People's Party) 7,7% 14 Red-Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) 13 6,9% Det Konservative Folkeparti (Conservative People's Party) 6,6% 12 The Alternative (Alternativet) 3% 5 The New Right (Nye Borgerlige) 2,4% 4 Liberal Alliance (Liberal Alliance) 2,3% 4 Others <1 % 0 Faroe Islands Union Party (Sambandsflokkurin) 28,8% 1 Javnaðarflokkurin (Social Democratic Party) 25,5% 1 Greenland Inuit Ataqatigiit (Inuit Community) 33,4% 1 Siumut 29,4% 1 Forward 179 Turnout: 84.6% 3. -

Codebook CPDS I 1960-2012

1 Codebook: Comparative Political Data Set I, 1960-2012 Codebook: COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET I 1960-2012 Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler The Comparative Political Data Set 1960-2012 is a collection of political and institutional data which have been assembled in the context of the research projects “Die Handlungs- spielräume des Nationalstaates” and “Critical junctures. An international comparison” di- rected by Klaus Armingeon and funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. This data set consists of (mostly) annual data for 23 democratic countries for the period of 1960 to 2012. In the cases of Greece, Spain and Portugal, political data were collected only for the democratic periods1. The data set is suited for cross national, longitudinal and pooled time series analyses. The data set contains some additional demographic, socio- and economic variables. Howev- er, these variables are not the major concern of the project and are thus limited in scope. For more in-depth sources of these data, see the online databases of the OECD. For trade union membership, excellent data for European trade unions are available on CD from the Data Handbook by Bernhard Ebbinghaus and Jelle Visser (2000). A few variables have been copied from a data set collected by Evelyne Huber, Charles Ragin, John D. Stephens, David Brady and Jason Beckfield (2004). We are grateful for the permission to include these data. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner and Sarah Engler. -

Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949-2019

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2020/17 Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949-2019 Yonatan Berman August 2020 Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949{2019 Yonatan Berman∗ y August 20, 2020 Abstract This paper draws on pre- and post-election surveys to address the long run evolution of vot- ing patterns in Israel from 1949 to 2019. The heterogeneous ethnic, cultural, educational, and religious backgrounds of Israelis created a range of political cleavages that evolved throughout its history and continue to shape its political climate and its society today. De- spite Israel's exceptional characteristics, we find similar patterns to those found for France, the UK and the US. Notably, we find that in the 1960s{1970s, the vote for left-wing parties was associated with lower social class voters. It has gradually become associated with high social class voters during the late 1970s and later. We also find a weak inter-relationship between inequality and political outcomes, suggesting that despite the social class cleavage, identity-based or \tribal" voting is still dominant in Israeli politics. Keywords: Political cleavages, Political economy, Income inequality, Israel ∗London Mathematical Laboratory, The Graduate Center and Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality, City University of New York, [email protected] yI wish to thank Itai Artzi, Dror Feitelson, Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´ınez-Toledano, and Thomas Piketty for helpful discussions and comments, and to Leah Ashuah and Raz Blanero from Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality for historical data on parliamentary elections in Tel Aviv.