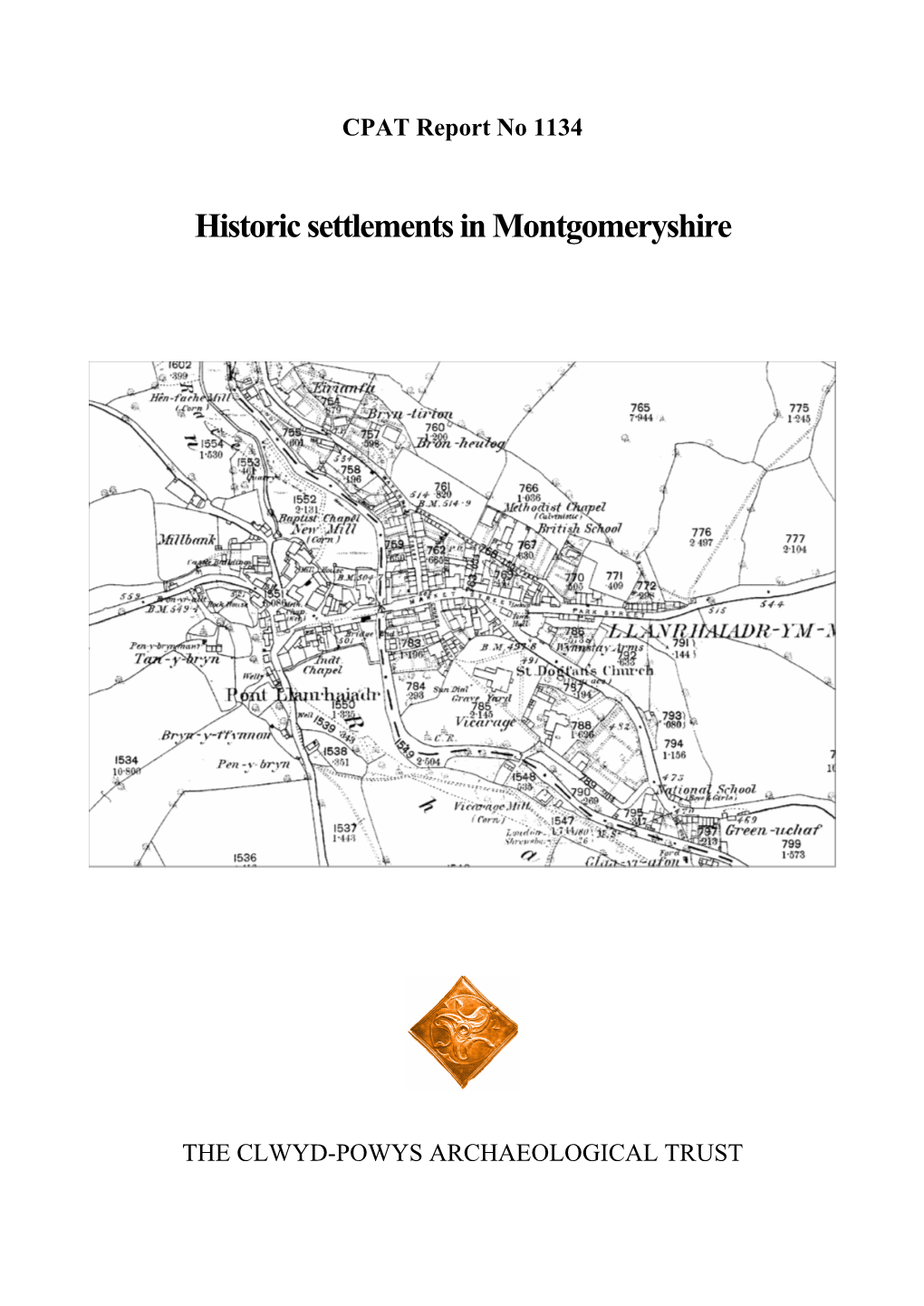

Historic Settlements in Montgomeryshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement – Volume 1: Chapter 7 Cultural Heritage

Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement – Volume 1 : Chapter 7 Cultural Heritage 900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00020 Final issue | September 2017 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 244562 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd The Arup Campus Blythe Gate Blythe Valley Park Solihull B90 8AE United Kingdom www.arup.com Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement – Volume 1: Chapter 7 Cultural Heritage Contents Page 7 Cultural Heritage 1 7.1 Introduction 1 7.2 Legislation, Policy Context and Guidance 1 7.3 Study Area 6 7.4 Methodology 6 7.5 Baseline Environment 12 7.6 Potential Construction Effects - Before Mitigation 34 7.7 Potential Operational Effects - Before Mitigation 36 7.8 Mitigation and Monitoring 37 7.9 Construction Effects - With Mitigation 38 7.10 Operational Effects - With Mitigation 38 7.11 Assessment of Cumulative Effects 38 7.12 Inter-relationships 38 7.13 Summary 38 900237-ARP-ZZ-ZZ-RP-YE-00020 | Final issue | September 2017 Llywodraeth Cymru / Welsh Government A487 New Dyfi Bridge Environmental Statement – Volume 1: Chapter 7 Cultural Heritage 7 Cultural Heritage 7.1 Introduction 7.1.1 This chapter provides an assessment of the Scheme in relation to archaeology and cultural heritage. It encompasses standing monuments, historic structures, buried archaeology and areas of heritage value such as historic landscapes, parks and gardens and Conservation Areas. -

2 Powys Local Development Plan Written Statement

Powys LDP 2011-2026: Deposit Draft with Focussed Changes and Further Focussed Changes plus Matters Arising Changes September 2017 2 Powys Local Development Plan 2011 – 2026 1/4/2011 to 31/3/2026 Written Statement Adopted April 2018 (Proposals & Inset Maps published separately) Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 This page left intentionally blank Cyngor Sir Powys County Council Adopted Powys Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Foreword I am pleased to introduce the Powys County Council Local Development Plan as adopted by the Council on 17th April 2017. I am sincerely grateful to the efforts of everyone who has helped contribute to the making of this Plan which is so important for the future of Powys. Importantly, the Plan sets out a clear and strong strategy for meeting the future needs of the county’s communities over the next decade. By focussing development on our market towns and largest villages, it provides the direction and certainty to support investment and enable economic opportunities to be seized, to grow and support viable service centres and for housing development to accommodate our growing and changing household needs. At the same time the Plan provides the protection for our outstanding and important natural, built and cultural environments that make Powys such an attractive and special place in which to live, work, visit and enjoy. Our efforts along with all our partners must now shift to delivering the Plan for the benefit of our communities. Councillor Martin Weale Portfolio Holder for Economy and Planning -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

X75 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

X75 bus time schedule & line map X75 Shrewsbury - Rhayader View In Website Mode The X75 bus line (Shrewsbury - Rhayader) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Llangurig: 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM (2) Llanidloes: 1:25 PM - 5:50 PM (3) Newtown: 5:05 PM (4) Rhayader: 2:35 PM (5) Shrewsbury: 6:30 AM - 3:45 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest X75 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next X75 bus arriving. Direction: Llangurig X75 bus Time Schedule 55 stops Llangurig Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM Bus Station, Shrewsbury Tuesday 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM Lloyds Chemist, Shrewsbury Smithƒeld Road, Shrewsbury Wednesday 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM Mardol Jct, Shrewsbury Thursday 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM King's Head Passage, Shrewsbury Friday 7:30 AM - 4:30 PM St Georges Court Jct, Frankwell Saturday 8:35 AM - 4:30 PM Copthorne Gate, Shrewsbury Pengwern Road Jct, Copthorne Stuart Court, Shrewsbury X75 bus Info Lindale Court Jct, Copthorne Direction: Llangurig Stops: 55 Barracks, Copthorne Trip Duration: 145 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Shrewsbury, Lloyds Richmond Drive Jct, Copthorne Chemist, Shrewsbury, Mardol Jct, Shrewsbury, St Copthorne Road, Shrewsbury Georges Court Jct, Frankwell, Pengwern Road Jct, Copthorne, Lindale Court Jct, Copthorne, Barracks, Shelton Road Jct, Copthorne Copthorne, Richmond Drive Jct, Copthorne, Shelton Copthorne Roundabout, Shrewsbury Road Jct, Copthorne, Co - Op, Copthorne, Swiss Farm Road Jct, Copthorne, Hospital, Copthorne, Co - Op, Copthorne Racecourse -

Königreichs Zur Abgrenzung Der Der Kommission in Übereinstimmung

19 . 5 . 75 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 128/23 1 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . April 1975 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG (Vereinigtes Königreich ) (75/276/EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN 1973 nach Abzug der direkten Beihilfen, der hill GEMEINSCHAFTEN — production grants). gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro Als Merkmal für die in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buch päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, stabe c ) der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG genannte ge ringe Bevölkerungsdichte wird eine Bevölkerungs gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75/268/EWG des Rates ziffer von höchstens 36 Einwohnern je km2 zugrunde vom 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berg gelegt ( nationaler Mittelwert 228 , Mittelwert in der gebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebie Gemeinschaft 168 Einwohner je km2 ). Der Mindest ten (*), insbesondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2, anteil der landwirtschaftlichen Erwerbspersonen an der gesamten Erwerbsbevölkerung beträgt 19 % auf Vorschlag der Kommission, ( nationaler Mittelwert 3,08 % , Mittelwert in der Gemeinschaft 9,58 % ). nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments , Eigenart und Niveau der vorstehend genannten nach Stellungnahme des Wirtschafts- und Sozialaus Merkmale, die von der Regierung des Vereinigten schusses (2 ), Königreichs zur Abgrenzung der der Kommission mitgeteilten Gebiete herangezogen wurden, ent sprechen den Merkmalen der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : der Richtlinie -

'IARRIAGES Introduction This Volume of 'Stray' Marriages Is Published with the Hope That It Will Prove

S T R A Y S Volume One: !'IARRIAGES Introduction This volume of 'stray' marriages is published with the hope that it will prove of some value as an additional source for the familv historian. For economic reasons, the 9rooms' names only are listed. Often people married many miles from their own parishes and sometimes also away from the parish of the spouse. Tracking down such a 'stray marriage' can involve fruitless and dishearteninq searches and may halt progress for many years. - Included here are 'strays', who were married in another parish within the county of Powys, or in another county. There are also a few non-Powys 'strays' from adjoining counties, particularly some which may be connected with Powys families. For those researchers puzzled and confused by the thought of dealing with patronymics, when looking for their Welsh ancestors, a few are to be found here and are ' indicated by an asterisk. A simple study of these few examples may help in a search for others, although it must be said, that this is not so easy when the father's name is not given. I would like to thank all those members who have helped in anyway with the compilation of this booklet. A second collection is already in progress; please· send any contributions to me. Doreen Carver Powys Strays Co-ordinator January 1984 WAL ES POWYS FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY 'STRAYS' M A R R I A G E S - 16.7.1757 JOHN ANGEL , bach.of Towyn,Merioneth = JANE EVANS, Former anrl r·r"~"nt 1.:ount les spin. -

Berriew Newsletter

BERRIEW NEWSLETTER Berriew Glanrhiew and the Aqueduct. Photograph sent to us by Ferol Richards. NUMBER 384 AUGUST 2020 BERRIEW DEFIBRILLATOR PLEASE REMEMBER A DEFIBRILLATOR (AED) IS LOCATED IN THE VILLAGE AT: THE FRONT ENTRANCE TO THE COMMUNITY CENTRE. ACCESS CODE: 1111 BERRIEW STORES, NEWS FROM THE SHOP The village is gradually getting a little busier, and its lovely to see The Talbot and The Lion opening again. We have lifted the barriers so customers can now walk around the shop and we can allow 3 customers at a time now. We would ask please keep to the social distancing rules and please stand behind the screen when we are serving at the Post Office. We have now extended both the shop hours and the Post Office which I hope will help, but if we do need to change these, due to sickness or holidays we will let you know. Laura has now joined us full time which is wonderful news and is proving an asset to the shop. We have now managed to get Plaster for the back room and the workmen have been beavering away in the evenings for us. As soon as this is dry Dave will be decorating, so we hope the back room will be finished soon. We have had another 2 chillers delivered this week so we have a new food to go fridge and the other chiller will be part of our Cheese and Charcuterie display. We are still accepting grocery deliveries, orders can be made by either telephoning or by email to [email protected] As usual many thanks for all your support, its been a tough few months but Kirsty, myself and Laura have had a few laughs and also a big thank you to Sarah for keeping us fed at lunchtimes!! Berriew Stores Opening Hours until further notice. -

Asking Price £270,000 31 Felin Hafren, Abermule, Montgomery, Powys

FOR SALE 31 Felin Hafren, Abermule, Montgomery, Powys, SY15 6NE FOR SALE Asking price £270,000 Indicative floor plans only - NOT TO SCALE - All floor plans are included only as a guide 31 Felin Hafren, Abermule, and should not be relied upon as a source of information for area, measurement or detail. Montgomery, Powys, SY15 6NE Energy Performance Ratings Property to sell? We would be who is authorised and regulated delighted to provide you with a free by the FCA. Details can be no obligation market assessment provided upon request. Do you Four/ Five bedroom detached family home situated on a quiet cul de sac location of your existing property. Please require a surveyor? We are in the popular village of Abermule between Welshpool and Newtown. Lovely contact your local Halls office to able to recommend a completely make an appointment. Mortgage/ independent chartered surveyor. views to the rear. The current owners have converted the garage into a bedroom financial advice. We are able Details can be provided upon but could be used as a playroom or home office, downstairs W.C., master to recommend a completely request. independent financial advisor, bedroom with en suite, utility room, conservatory, off road parking, workshop in the rear garden has power and water supply. Early viewing advised. 01938 555 552 Welshpool office: 14 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7SD E. [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICE. Halls Holdings Ltd and any joint agents for themselves, and for the Vendor of the property whose Agents they are, give notice that: -

Delegated List.Xlsx

Delegated List 91 Applications Excel Version Go Back Parish Name Decision Date Application Application No.Application Type Date Decision Proposal Location Abermule And Approve 06/04/2018 DIS/2018/0066Discharge of condition 05/07/2019Issued Discharge of conditions Upper Bryn Llandyssil 15, 18, 24 & 25 of Abermule planning approval Newtown Community P/2017/1264 Powys SY15 6JW Approve 15/01/2019 19/0028/FULFull Application 02/07/2019 Conversion of existing Cloddiau agricultural barn to Aberbechan residential use in Newtown connection with the Powys existing dwelling and SY16 3AS installation of Septic tank (part retrospective) Approve 25/02/2019 19/0283/CLECertificate of 05/07/2019 Section 191 application Maeshafren Lawfulness - Existing for a Certificate of Abermule Lawfulness for an Newtown Existing Use in relation to Powys the use of former SY15 6NT agricultural buildings as B2 industrial Approve 17/05/2019 19/0850/TREWorks to trees in 26/06/2019 Application for works to 2 Land 35M SSE Of Coach Conservation Area no. wild cherry trees in a House conservation area Llandyssil Montgomery Powys SY15 6LQ CODE: IDOX.PL.REP.05 24/07/2019 13:48:43 POWYSCC\\sandraf Go Back Page 1 of 17 Delegated List 91 Applications Permitted 01/05/2019 19/0802/ELEElectricity Overhead 26/06/2019 Section 37 application 5 Brynderwen Developm Line under the Electricity Act Abermule 1989 Overhead Lines Montgomery ent (exemption) (England and Powys Wales) Regulations 2009 SY15 6JX to erect an additional pole Berriew Approve 24/07/2018 18/0390/REMRemoval or Variation 28/06/2019 Section 73 application to Maes Y Nant Community of Condition remove planning Berriew condition no. -

Berriew Newsletter

BERRIEW NEWSLETTER NUMBER 367 FEBRUARY 2019 The Parish of Berriew Vicar: Revd Alexis Smith 01686 641992 Assistant Priest: Revd Esther Yates 01686 625559 Lay Reader: Mr Peter Watkin 01686 640640 Sub-Warden: Mr Jim Maxwell 01686 640840 Sub-Warden: Mrs Iris Tombs 01686 640400 Services in St Beuno’s, Berriew Sunday 3rd February – Candlemas 10.00am All Age Family Service ****** Sunday 10th February – 4th before Lent 10.00am Holy Communion Sunday 17th February – 3rd before Lent 10.00am All Age Family Service Sunday 24th February – 2nd before Lent 10.00am Holy Communion Please note that as from the beginning of February St Beuno’s will have 2 services of Holy Communion and 2 All Age services, in order to serve everyone – and to allow our priests to operate non- eucharistic services. You will be aware that our vicar has responsibility for 6 churches. We hope this will encourage all our church family, young and old, to share worship together. There will be coffee/tea/juice and biscuits in the Old School after both All Age services – an opportunity for us to share in fellowship. Please support us as we try to serve all of our community. St. John’s Mission Church - Fron Sunday 10th February 9.00am All Age Worship th Sunday 24 February 9.00am Family Communion Pantyffridd Church Sunday 3rd February 3.00pm Evening Prayer Sunday 17th February 3.00pm Holy Communion Parish News Wednesdays at 10.30am Our morning services will also have a small change. On the 1st and 3rd Wednesday we shall have Holy Communion in church. -

16 Maesgarmon Close Castle Caereinion, Welshpool, SY21 9BQ

Chartered Surveyors Auctioneers Estate Agents Established 1862 www.morrismarshall.co.uk 16 Maesgarmon Close Castle Caereinion, Welshpool, SY21 9BQ • Spacious Semi-Detached Village House. • Oil Fired Heating. UPVC Double Glazing. • Sitting Room, Dining Area. • Integral Garage with ample parking to front. • Light Oak Kitchen with built-in appliances. • Well presented rear garden and patio. • Conservatory with open views to Golfa Hill. • Cul-de-sac location. • Three Bedrooms, Bathroom, Separate W.C. • Energy efficiency rating = 59 £169,950 WELSHPOOL OFFICE 01938 554818 [email protected]. uk lagged cylinder and immersion heater. Situated on the outskirts of the village Main Bedroom (front) 4.52m x 4.35m exc which has primary school education, wardrobe (14'10" x 14'3" exc wardrobe) general stores, public house and Church ad Radiator. Built-in sliding mirror fronted being convenient to Welshpool, Newtown wardrobes to one wall. and Llanfair Caereinion. Bedroom (front) 4.67m x 2.45m (15'4" x 8'0") Radiator. Constructed of timber frame with brick outer wall under a tiled roof, with Bedroom (rear) 3.9m x 2.85m (12'10" x Accommodation comprising:- 9'4") Radiator (views to rear).Built-in wardrobe with louvre fronted doors. UPVC double glazed Entrance Door to Separate W.C with radiator. Entrance Hall which leads via a panelled Bathroom With white suite (2012) internal door to:- comprising panelled bath and overhead Sitting Room 4.86m x 4.7m (15'11" x 15'5") electric shower and folding splash screen, Recessed fire surround (temporarily sealed) vanity wash bain with cupboards beneath. with overmantel. Radiator. Mainly wall tiled.