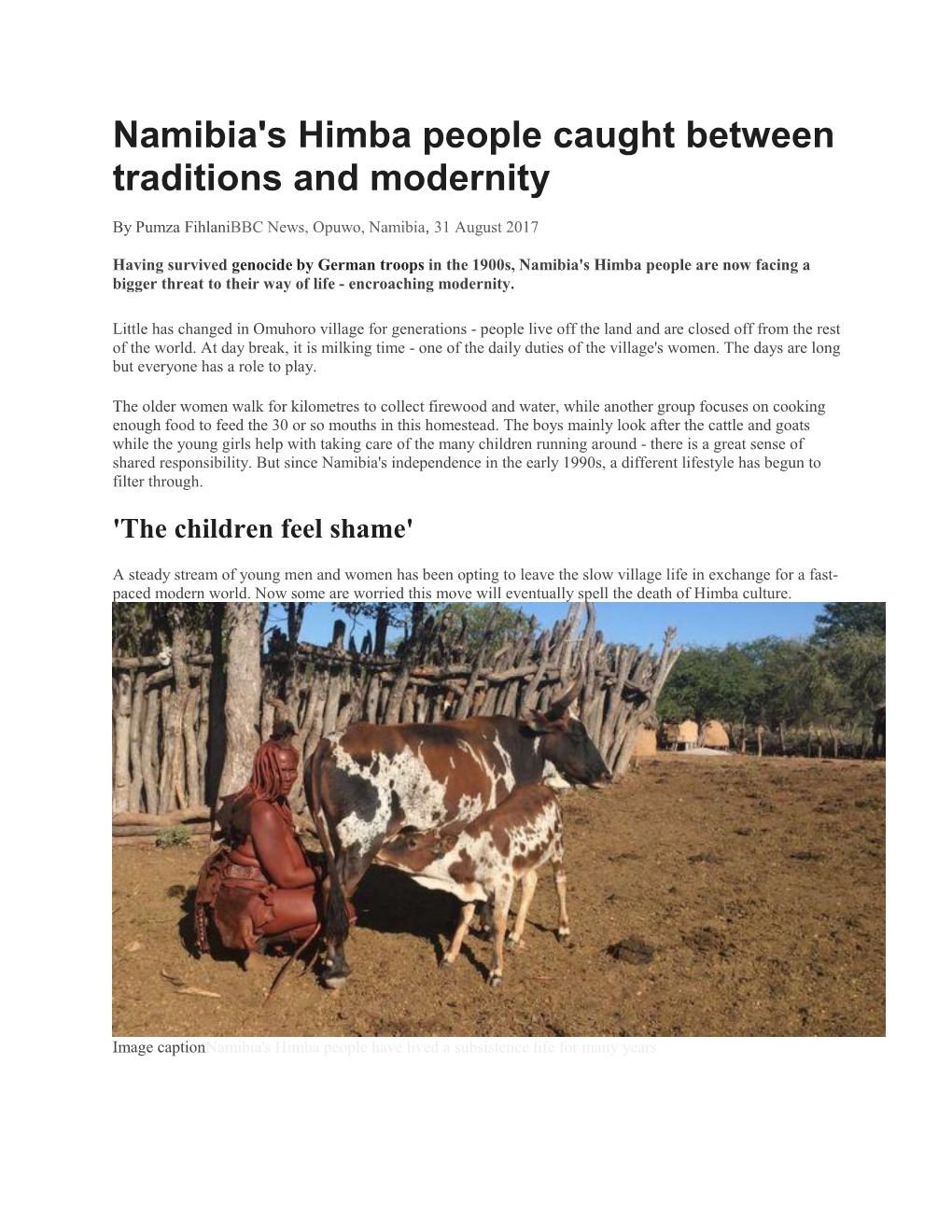

Namibia's Himba People Caught Between Traditions and Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W

T 0 ~ume ~-723X)Southern i\fric-a 7, Japuary-wruarv 1997 Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W. Congress Parkway, Chicago, IL 60624 phone (773) 826-4481 fax (773) 533-4728 TEARS, FEARS, AND HOPES: Healing the Memories in South Africa Pastor Philip Knutson of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, reports on a workshop he and other church leaders attended. "The farmer tied my grandfather up to a pole and told him he must get rid of all his cattle.. .! was just a boy then but I will never forget that.. .! could have been a wealthy farmer today if our fam ily had not been dispossessed in that way." The tears streamed down his face as this "coloured" pastor related his most painful experience of the past to a group at a workshop entitled "Exploring Church Unity Within the Context of Healing and Reconciliation" held in Port Elizabeth recently. A black Methodist pastor related his feelings of anger and loss at being deprived of a proper education. Once while holding a service to commemorate the young martyrs ofthe June 1976 Uprising, his con gregation was attacked and assaulted in the church. What hurt most, he said, was that the attacking security forces were black. The workshop, sponsored by the Provincial Council of Churches, was led by Fr. Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest who lost both hands and an eye in a parcel bomb attack in Harare in 1990. In his new book Partisan and Priest and in his presenta tion he said that every South African has three stories to tell. -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Threatened Pastures

Himba of Namibia and Angola Threatened pastures ‘All the Himba were born here, next to the river. When the Himba culture is flourishing and distinctive. All Himba cows drink this water they become fat, much more than if are linked by a system of clans. Each person belongs to they drink any other water. The green grass will always two separate clans; the eanda, which is inherited though grow, near the river. Beside the river grow tall trees, and the mother, and the oruzo, which is inherited through the vegetables that we eat. This is how the river feeds us. father. The two serve different purposes; inheritance of This is the work of the river.’ cattle and other movable wealth goes through the Headman Hikuminue Kapika mother’s line, while dwelling place and religious authority go from father to son. The Himba believe in a A self-sufficient people creator God, and to pray to him they ask the help of their The 15,000 Himba people have their home in the ancestors’ spirits. It is the duty of the male head of the borderlands of Namibia and Angola. The country of the oruzo to pray for the welfare of his clan; he prays beside Namibian Himba is Kaoko or Kaokoland, a hot and arid the okuruwo, or sacred fire. Most important events region of 50,000 square kilometres. To the east, rugged involve the okuruwo; even the first drink of milk in the mountains fringe the interior plateau falling toward morning must be preceded by a ritual around the fire. -

Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa: the Tragedy of Endowment

alao.mech.2 5/23/07 1:42 PM Page 1 “Here is another important work from one of Africa’s finest scholars on Conflict and Security Studies. Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa is a treasure of scholarship and insight, with great depth and thoroughness, and it will put us in Abiodun Alao’s debt for quite some NATURAL RESOURCES time to come.” —Amos Sawyer, Co-director, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University AND CONFLICT “As extensive in information as it is rich in analysis, Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa IN AFRICA should help this generation of scholars appreciate the enormity and complexity of Africa’s conflicts and provide the next generation with a methodology that breaks down disciplinary boundaries.” —Akanmu G. Adebayo, Executive Director, Institute for Global Initiatives, Kennesaw State University THE TRAGEDY “Abiodun Alao has provided us with an effulgent book on a timely topic. This work transcends the perfunctory analyses that exist on natural resources and their role in African conflicts.” OF ENDOWMENT —Abdul Karim Bangura, Researcher-In-Residence at the Center for Global Peace, and professor of International Relations and Islamic Studies, School of International Service, American University onflict over natural resources has made Africa the focus of international attention, particularly during the last decade. From oil in Nigeria and diamonds in the Democra- Abiodun Alao Ctic Republic of Congo, to land in Zimbabwe and water in the Horn of Africa, the poli- tics surrounding ownership, management, and control of natural resources has disrupted communities and increased external intervention in these countries. -

The Indigenous Economic System in Northwest Namibia: Maintaining the Himba Tradition Through the Exchange with Others

THE INDIGENOUS ECONOMIC SYSTEM IN NORTHWEST NAMIBIA: MAINTAINING THE HIMBA TRADITION THROUGH THE EXCHANGE WITH OTHERS MIYAUCHI Yohei Department of Anthropology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown 6140, South Africa E-mail: [email protected] This study examines how the indigenous economy is interwoven with the modern global economy in contemporary Southern Africa by focusing on modes of exchange in Kaokoland, northwest Namibia. Himba pastoralists are the main residents of Kaokoland. Although they are recognized as the most traditional and marginalized people in Namibia, in reality, most have active relationships with neighboring peoples such as the Herero (traditionally pastoralists), the Owambo (traditionally agro-pastoralists, although many are now urban dwellers), and the Damara (agriculturalists). The Himba people keep their traditional way of life in terms of their traditional costumes and heavy dependence on livestock. At the same time, they are becoming involved in modern issues such as the development of a hydroelectric dam, the exchange of their livestock in modern livestock markets that were once forbidden, and participation in a flourishing tourism industry with many foreign tourists visiting their homesteads. A supermarket owned by white people also recently opened in Kaokoland, at which some of the Himba shop. However, most of the Himba have no source of cash income except for the occasional sales of their cattle. The area has a few informal markets or open marketplaces, where the Himba generally barter their goats for commodities and foods brought by the Owambo merchants and Damara agriculturalists. In many ways, goats serve as a sort of regional currency. In this paper, I describe some specific cases of economic exchanges in this area and propose the concept of an “indigenous economic system,” which defines how the traditional economy in remote Namibia is entangled with the modern global economy through people’s actual daily lives. -

Himba People Culture

Himba People Total population: about 50,000 Languages: OtjiHimba (Herero language dialect) Religion: Monotheistic (Mukuru and Ancestor Reverence) Related ethnic groups: Herero people, Bantu peoples Himba / OvaHimba / Himba (OmuHimba) woman The Himba (singular: OmuHimba, plural: OvaHimba) are indigenous peoples with an estimated population of about 50,000 people living in northern Namibia, in the Kunene region (formerly Kaokoland) and on the other side of the Kunene River in Angola.[1] There are also a few groups left of the Ovatwa, who are also OvaHimba, but are hunters and gatherers. The OvaHimba are a semi-nomadic, pastoral people, culturally distinguishable from the Herero people in northern Namibia and southern Angola, and speak OtjiHimba (a Herero language dialect), which belongs to the language family of the Bantu.[1] The OvaHimba are considered the last (semi-) nomadic people of Namibia. Culture Subsistence economy The OvaHimba are predominantly livestock farmers who breed fat-tailed sheep and goats, but count their wealth in the number of their cattle. They also grow and farm rain-fed-crops such as maize and millet. Livestock are the major source of milk and meat for the OvaHimba, their milk-and-meat nutrition diet is also supplemented by maize cornmeal, chicken eggs, wild herbs and honey. Only occasionally, and opportunistically, are the livestock sold for cash. Non-farming businesses, wages and salaries, pensions, and other cash remittances make up a very small portion of the OvaHimba livelihood, which is gained chiefly from -

Examining the Relationship Between the Namibian Government and the Himba of Epupa Falls by Adrian Bradley Borrego

Examining the Relationship Between the Namibian Government and the Himba of Epupa Falls Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Borrego, Adrian Bradley Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 19:20:15 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624916 EXAMINING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE NAMIBIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE HIMBA OF EPUPA FALLS BY ADRIAN BRADLEY BORREGO ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College A Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors Degree with Honors in Environmental Science THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY 2017 Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Thomas Wilson The Honors College ABSTRACT Namibia, located in southwest Africa, is comprised of twelve different indigenous peoples with different histories and cultures. One indigenous group, the Himba, occupy the Kunene Region in the North. This project examined the interaction between the Himba of Epupa Falls and the Namibian government using interviews conducted between June 26th to June 28th of 2016. One of the major topics to be addressed is conservancies and ecotourism, which is the biggest contributor to the Namibian economy. The goal of the study was to determine how the Himba view the actions of their government and what they want from it going forward. The main findings were that the Himba have very little interaction with their government and the conservancy that they live on, and are mostly concerned with their day-to-day life. -

Dams, Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Minorities

WCD Thematic Reviews Social Issues I.2 Sharing Power Dams, Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Minorities Final Version : November 2000 Prepared for the World Commission on Dams (WCD) by: Marcus Colchester - Forest Peoples Programme Secretariat of the World Commission on Dams P.O. Box 16002, Vlaeberg, Cape Town 8018, South Africa Phone: 27 21 426 4000 Fax: 27 21 426 0036. Website: http://www.dams.org E-mail: [email protected] World Commission on Dams Orange River Development Project, South Africa, Draft, October 1999 i Disclaimer This is a working paper of the World Commission on Dams - the report published herein was prepared for the Commission as part of its information gathering activity. The views, conclusions, and recommendations are not intended to represent the views of the Commission. The Commission's views, conclusions, and recommendations will be set forth in the Commission's own report. Please cite this report as follows: Colchester, M. 2000 - Forest Peoples Programme : Dams, Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Minorities, Thematic Review 1.2 prepared as an input to the World Commission on Dams, Cape Town, www.dams.org The WCD Knowledge Base This report is one component of the World Commission on Dams knowledge base from which the WCD drew to finalize its report “Dams and Development-A New Framework for Decision Making”. The knowledge base consists of seven case studies, two country studies, one briefing paper, seventeen thematic reviews of five sectors, a cross check survey of 125 dams, four regional consultations and nearly 1000 topic-related -

42 Terra Mater

42 TERRA MATER ETHNOLOGY Between worlds For 400 years, the nomadic Himba peoples lived in northwestern Namibia, unaffected by the rest of the world. But in recent years, the government and modern civilisation have been causing difficulties for them. There is now a question over how long the Himba have to preserve their way of life Words: Fabian von Poser Photography: Günther Menn TERRA MATER 43 ETHNOLOGY 44 TERRA MATER Cattle is the most important thing that the Himba own. They believe that, alongside humans, these animals are the only beings with a soul TERRA MATER 45 ETHNOLOGY The old world clashes with the new in the supermarket of Opuwo. Every three or four weeks the Himba women come from their kraal to do their shopping here 46 TERRA MATER TERRA MATER 47 ETHNOLOGY The Himba live a traditional lifestyle. Rules, rituals and daily routines have changed little since the tribe immigrated to northern Namibia in the 16th century T IS STILL DARK when Rituapi approaches her hut and walks over to the fire. She sits with I the other women of the village of Epaco, just like every morning, crowded together in silence, their faces lit by the flames. They drink tea made from the leaves of the miracle bush. A golden beam of light on the horizon heralds the rising sun, and children are already rounding up goats and cattle to lead them to the nearest waterhole – a walk of one and a half hours along dusty paths. They leave early to avoid the scorching midday heat. The men of the village are far away. -

Extractive Industries, Land Rights and Indigenous Populations’/Communities’ Rights

Industries extractives, Droits fonciers et Droits des Populations/Communautés autochtones autochtones Populations/Communautés des Droits et fonciers Droits extractives, Industries Extractive Industries, Land Rights and Indigenous Populations’/Communities’ Rights Report of the African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities Extractive Industries, Land Rights and Indigenous Populations’/Communities’ Rights East, Central and Southern Africa Submitted in accordance with the ”Resolution on the Rights of Indigenous Populations/Communities in Africa” Adopted by The African Commission on Human and Peoples’s Rights at its 58th Ordinary Session 2017 Report of the African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities Extractive Industries, Land Rights and Indigenous Populations’/Communities’ Rights Copyright: IWGIA Typesetting and Layout: Jorge Monrás Prepress and print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 978-87-92786-76-0 AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS (ACHPR) No 31 Bijilo Annex Layout, Kombo North District, Western Region – P.O.Box 673 – Banjul, The Gambia Tel: (+220) 441 05 05/441 05 06 – E-mail: [email protected] – Web: www.achpr.org INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 – Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (+45) 35 27 05 00 – E-mail: [email protected] – Web: www.iwgia.org The report has been produced with the financial support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs Table of contents Acronyms and Abbreviations ...................................................................................6 -

The Ovahimba, the Proposed Epupa Dam, the Independent Namibian State, and Law and Development in Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY School of Law 2001 "God Gave Us This Land:" The OvaHimba, the Proposed Epupa Dam, the Independent Namibian State, and Law and Development in Africa Sidney Harring CUNY School of Law How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/260 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] "God Gave Us This Land": the OvaHimba, the Proposed Epupa Dam, the Independent Namibian State, and Law and Development in Africa SIDNEY L. HARRING* CONTENTS I. Introduction ....................................... 36 II. History of the OvaHimba in Angola and Namibia ............... 39 A. The Himba ..................................... 39 B. The Emergence of the Himba as a Distinct People ........... 40 C. The German Arrival in South West Africa ................. 41 D. Pastoral Culture and Property Rights ...................... 42 E. Grazing Rights ...................................... 43 1. Background .................................... 43 2. General Communal System of Grazing ................. 44 3. The Himba and Early Colonial Administrators ............ 46 4. The Odendall Commission and South African Political Divisions ...................................... 47 G. The Modem Himba Dichotomy: Traditional Life Versus History of Accommodation to Different Colonial Governments ........ 48 III. The Epupa Dam, the Kunene River, and Namibian Development ..... 50 A. Modem Dam Building ................................ 50 B. Plans for Damming the Kunene River ..................... 50 1. Water and Namibian Development .................... 50 2. German Colonial Planning .......................... 51 3. South African Colonial Authorities' Development of the River ......................................... 52 a. Use of Falls and Rivers as Power Sources .........