Dams, Indigenous Peoples and Ethnic Minorities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fourth Poetry Collection Honours Intense Suffering and Immeasurable Beauty Randy Lundy Reassures Readers That Despite Darker Moments, Now He Is Okay by Ariel Gordon

FEATURING NEW WORKS FREE FROM ALBERTA, SASKATCHEWAN, #76 | Spring/Summer 2020 prairiebooksnow.ca AND MANITOBA you’ll also find: Untangling public-private partnerships reveals ideological bias inside Crime, bombast, and falsehoods New books by come together in new novel Un roman jeunesse où jeux vidéo randy doreen et communauté se mêlent / Young lundy vanderstoop Traveller turned poet builds a home, adult novel blends video games with keeps moving community One-act play builds on life experience And more online exclusives on our in transitioning new website, prairiebooksnow.ca! Couple’s storybook series written for own children come to life Publications Mail Agreement Number 40023290 20 years later Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to: Association of Manitoba Book Publishers COURTNEY BARR COURTNEY 404–100 Arthur Street, Winnipeg, MB R3B 1H3 NEW FROM FERNWOOD PUBLISHING Challenging the Right, Augmenting the Left: NOlympians: Recasting Leftist Imagination Inside the Fight Against Capitlist Mega-Sports edited by Robert Latham, Julian von Bargen, in Los Angeles, Tokyo, & Beyond A.T. Kingsmith, Niko Block by Jules Boykoff July 2020 Ideology Over Economics: The Socialist Challenge Today: P3s in an Age of Austerity Syriza, Corbyn, Sanders by John Loxley by Leo Panitch & Sam Gindin July 2020 with Stephen Maher www.fernwoodpublishing.ca 76spring/ summer 2020 On the cover: Artwork by Sheldon Dawson from Louis Riel Day (page 17). Sheldon’s culturally sensitive illustrations help teach positive, healthy, and traditional lifestyles and provide -

Social and Environmental Effects of Bujagali Dam

FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT Department of Building, Energy and Environmental Engineering SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF BUJAGALI DAM MUWUMUZA LINDA 2014 MASTER OF SCIENCE THESIS, Credits: H.E 30 DIVISION OF SUSTAINABLE ENERGY Supervisor: DR. JEEVAN JAYASURIYA A/PROF DR. JOHN BAPTIST KIRABIRA Dedication Well yes Mum, I did as we discussed and so this is for you. You spoke, I listened and this is the outcome. I pray you are proud of me. Love you always. Acknowledgements I would love to thank the following people for their contribution towards the finishing of my project. I would not have finished it successfully without you. My Family Daddy Angella Stephen Amanda College of Engineering, Design, Art and Technology My local facilitators Dr. Sabiiti Adam Hillary Kasedde My Supervisors Dr. Jeevan Jayasuriya Dr. John Baptist Kirabira The Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development especially: Eng. Moses Murengezi: Advisor to the Chairman Energy and Mining Sector Working group Eng. Paul Mubiru: Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development The Bujagali Energy Limited Company especially: Mr. John Berry: Chief Executive Officer of BEL Ms. Achanga Jennifer: Environmental Engineer of BEL Francis Mwangi: Technical Manager Allan Ikahu: Infrastructure and Project Engineer My Friends: John, Anthony, Mue, Winnie, Arthur, Vincent, Hajarah, Fildah, Winnie, Richard and all the rest List of Acronyms ADB African Development Bank AES Applied Energy Services BEL Bujagali Energy Limited MEMD Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development NGO Non Government Organization O&M Energy Operations and Maintenance Energy Limited PAP Project Affected Persons USAID United States Agency for International Development Abstract There has been a steady increment in economic growth in Uganda and as the economy is on the rise, the demand for energy also increases. -

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block

EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura Final EIA Report Prepared for: Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited Prepared by: SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. June, 2016 EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari FINAL REPORT EIA & EC for Kathalchari Field Development, Block (AA-ONN-2002/1), Tripura M/s Jubilant Oil and Gas Private Limited For on and behalf of SENES Consultants India Ltd Approved by Mr. Mangesh Dakhore Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date 28.12.2015 Approved by Mr. Sunil Gupta Position held NABET-QCI Accredited EIA Coordinator for Offshore & Onshore Oil and Gas Development and Production Date February 2016 The EIA report preparation have been undertaken in compliance with the ToR issued by MoEF vide letter no. J-11011/248/2013-IA II (I) dated 28th January, 2014. Information and content provided in the report is factually correct for the purpose and objective for such study undertaken. SENES/M-ESM-20241/June, 2016 i JOGPL EIA for development activities of hydrocarbon, installation of GGS & pipeline laying at Kathalchari INFORMATION ABOUT EIA CONSULTANTS Brief Company Profile This Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) report has been prepared by SENES Consultants India Pvt. Ltd. SENES India, registered with the Companies Act of 1956 (Ranked No. 1 in 1956), has been operating in the county for more than 11 years and holds expertise in conducting Environmental Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments, Environment Health and Safety Compliance Audits, Designing and Planning of Solid Waste Management Facilities and Carbon Advisory Services. -

The State of Venezuela's Forests

ArtePortada 25/06/2002 09:20 pm Page 1 GLOBAL FOREST WATCH (GFW) WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE (WRI) The State of Venezuela’s Forests ACOANA UNEG A Case Study of the Guayana Region PROVITA FUDENA FUNDACIÓN POLAR GLOBAL FOREST WATCH GLOBAL FOREST WATCH • A Case Study of the Guayana Region The State of Venezuela’s Forests. Forests. The State of Venezuela’s Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page i The State of Venezuela’s Forests A Case Study of the Guayana Region A Global Forest Watch Report prepared by: Mariapía Bevilacqua, Lya Cárdenas, Ana Liz Flores, Lionel Hernández, Erick Lares B., Alexander Mansutti R., Marta Miranda, José Ochoa G., Militza Rodríguez, and Elizabeth Selig Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page ii AUTHORS: Presentation Forest Cover and Protected Areas: Each World Resources Institute Mariapía Bevilacqua (ACOANA) report represents a timely, scholarly and Marta Miranda (WRI) treatment of a subject of public con- Wildlife: cern. WRI takes responsibility for José Ochoa G. (ACOANA/WCS) choosing the study topics and guar- anteeing its authors and researchers Man has become increasingly aware of the absolute need to preserve nature, and to respect biodiver- Non-Timber Forest Products: freedom of inquiry. It also solicits Lya Cárdenas and responds to the guidance of sity as the only way to assure permanence of life on Earth. Thus, it is urgent not only to study animal Logging: advisory panels and expert review- and plant species, and ecosystems, but also the inner harmony by which they are linked. Lionel Hernández (UNEG) ers. -

Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W

T 0 ~ume ~-723X)Southern i\fric-a 7, Japuary-wruarv 1997 Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W. Congress Parkway, Chicago, IL 60624 phone (773) 826-4481 fax (773) 533-4728 TEARS, FEARS, AND HOPES: Healing the Memories in South Africa Pastor Philip Knutson of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, reports on a workshop he and other church leaders attended. "The farmer tied my grandfather up to a pole and told him he must get rid of all his cattle.. .! was just a boy then but I will never forget that.. .! could have been a wealthy farmer today if our fam ily had not been dispossessed in that way." The tears streamed down his face as this "coloured" pastor related his most painful experience of the past to a group at a workshop entitled "Exploring Church Unity Within the Context of Healing and Reconciliation" held in Port Elizabeth recently. A black Methodist pastor related his feelings of anger and loss at being deprived of a proper education. Once while holding a service to commemorate the young martyrs ofthe June 1976 Uprising, his con gregation was attacked and assaulted in the church. What hurt most, he said, was that the attacking security forces were black. The workshop, sponsored by the Provincial Council of Churches, was led by Fr. Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest who lost both hands and an eye in a parcel bomb attack in Harare in 1990. In his new book Partisan and Priest and in his presenta tion he said that every South African has three stories to tell. -

Constructing an Anthropology of Infrastructure

Journal of International and Global Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 6 6-1-2019 Constructing an Anthropology of Infrastructure Alfonso P. Castro Syracuse University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs Part of the Anthropology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Castro, Alfonso P. (2019) "Constructing an Anthropology of Infrastructure," Journal of International and Global Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs/vol10/iss2/6 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International and Global Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constructing an Anthropology of Infrastructure Review Essay by A. Peter Castro, Department of Anthropology, Syracuse University, [email protected]. Anand, Nikhil, Akhil Gupta, & Hannah Appel (Eds.). The Promise of Infrastructure. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018. Scudder. Thayer. Large Dams: Long-Term Impacts on Riverine Communities and Free-Flowing Rivers. Singapore: Springer, 2018. Infrastructure has become a hot topic in contemporary anthropology. By some accounts, this is a remarkable turnaround. According to Marco Di Nunzio (2018, p. 1), infrastructure was once largely ignored because anthropologists viewed the subject as “unexciting and irrelevant..., boring.” He claims that this supposed lack of interest was not snobbism but an outcome of “modernist representations” portraying infrastructure as “inert, nearly invisible” (p. 1). -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Badal Sircar

Badal Sircar Scripting a Movement Shayoni Mitra The ultimate answer [...] is not for a city group to prepare plays for and about the working people. The working people—the factory workers, the peasants, the landless laborers—will have to make and perform their own plays. [...] This process of course, can become widespread only when the socio-economic movement for emancipation of the working class has also spread widely. When that happens the Third Theatre (in the context I have used it) will no longer have a separate function, but will merge with a transformed First Theatre. —Badal Sircar, 23 November 1981 (1982:58) It is impossible to discuss the history of modern Indian theatre and not en- counter the name of Badal Sircar. Yet one seldom hears his current work talked of in the present. How is it that one of the greatest names, associated with an exemplary body of dramatic work, gets so easily lost in a haze of present-day ignorance? While much of his previous work is reverentially can- onized, his present contributions are less well known and seldom acknowl- edged. It was this slippage I set out to examine. I expected to find an ailing man reminiscing of past glories. I was warned that I might find a cynical per- son, an incorrigible skeptic weary of the world. Instead, I encountered an in- domitable spirit walking along his life path looking resolutely ahead. A kind old man who drew me a map to his house and saved tea for me in a thermos. A theatre person extraordinaire recounting his latest workshop in Laos, devis- ing how to return as soon as possible. -

Guri Hydro Power

CompanyCompany ProfileProfile ofof HPCHPC VenezuelaVenezuela C.A.C.A. (VHPC)(VHPC) HPCHPC VenezuelaVenezuela C.A.C.A. OctOct 20082008 CompanyCompany ProfileProfile ofof VHPCVHPC (1)(1) Hitachi Ltd. (Japan) 68%: Shareholder Hitachi Plant Technologies, Ltd (Japan) (HPT) 100%: Shareholder HPC Venezuela C.A. (VHPC) 2 CompanyCompany ProfileProfile ofof VHPCVHPC (2)(2) ¾ Affiliate company of Hitachi Plant Technologies Ltd, Japan (HPT):100% shareholder ¾ Project Execution Experience from 1978 (as HPT, Japan) ¾ Establishment date of VHPC: January 1988 ¾ Execution Experience: - Hydroelectric Power(Guri, Macagua, Caruachi) - Thermal Power (CADAFE,TACOA, ELEVAL) - Direct Reduction plant(OPCO, ORINOCO IRON) - Pellet Plant (FMO) - Railway Project-DEPOT (IAFE) 3 CompanyCompany ProfileProfile ofof VHPCVHPC (3)(3) ¾ Paid-in capital: 240,000,000 Bolivars ¾ Total Sales (from 1979 to present) : more than 600 MUS$ ¾ Main Bank: The bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ ltd / Banco Provincial Venezuela “Accumulated Local Management Know-how” “Advanced Technology Transferred from HPT Japan” 4 HistoryHistory ofof VHPCVHPC HPC Venezuela, C.A. was established in January 1988 1978 1988 Hitachi Plant Technologies ,Ltd HPC Venezuela, C.A (Former: Hitachi Plant Engineering and Construction Guri Dam Co., Ltd) Macagua Dam 5 Location:Location: Venezuela,Venezuela, PuertoPuerto OrdazOrdaz VHPC is located in Puerto Ordaz, Bolivar State of Venezuela Caracas Puerto Ordaz 6 BusinessBusiness AreaArea ofof HPTHPT ● Water treatment systems and equipment ●Large-size pumps ●Compressor -

Introduction to Bengali, Part I

R E F O R T R E S U M E S ED 012 811 48 AA 000 171 INTRODUCTION TO BENGALI, PART I. BY- DIMOCK, EDWARD, JR. AND OTHERS CHICAGO UNIV., ILL., SOUTH ASIALANG. AND AREA CTR REPORT NUMBER NDEA.--VI--153 PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICE MF -$1.50 HC$16.04 401P. DESCRIPTORS-- *BENGALI, GRAMMAR, PHONOLOGY, *LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION, FHONOTAPE RECORDINGS, *PATTERN DRILLS (LANGUAGE), *LANGUAGE AIDS, *SPEECHINSTRUCTION, THE MATERIALS FOR A BASIC COURSE IN SPOKENBENGALI PRESENTED IN THIS BOOK WERE PREPARED BYREVISION OF AN EARLIER WORK DATED 1959. THE REVISIONWAS BASED ON EXPERIENCE GAINED FROM 2 YEARS OF CLASSROOMWORK WITH THE INITIAL COURSE MATERIALS AND ON ADVICE AND COMMENTS RECEIVEDFROM THOSE TO WHOM THE FIRST DRAFT WAS SENT FOR CRITICISM.THE AUTHORS OF THIS COURSE ACKNOWLEDGE THE BENEFITS THIS REVISIONHAS GAINED FROM ANOTHER COURSE, "SPOKEN BENGALI,"ALSO WRITTEN IN 1959, BY FERGUSON AND SATTERWAITE, BUT THEY POINTOUT THAT THE EMPHASIS OF THE OTHER COURSE IS DIFFERENTFROM THAT OF THE "INTRODUCTION TO BENGALI." FOR THIS COURSE, CONVERSATIONAND DRILLS ARE ORIENTED MORE TOWARDCULTURAL CONCEPTS THAN TOWARD PRACTICAL SITUATIONS. THIS APPROACHAIMS AT A COMPROMISE BETWEEN PURELY STRUCTURAL AND PURELYCULTURAL ORIENTATION. TAPE RECORDINGS HAVE BEEN PREPAREDOF THE MATERIALS IN THIS BOOK WITH THE EXCEPTION OF THEEXPLANATORY SECTIONS AND TRANSLATION DRILLS. THIS BOOK HAS BEEN PLANNEDTO BE USED IN CONJUNCTION WITH THOSE RECORDINGS.EARLY LESSONS PLACE MUCH STRESS ON INTONATION WHIM: MUST BEHEARD TO BE UNDERSTOOD. PATTERN DRILLS OF ENGLISH TO BENGALIARE GIVEN IN THE TEXT, BUT BENGALI TO ENGLISH DRILLS WERE LEFTTO THE CLASSROOM INSTRUCTOR TO PREPARE. SUCH DRILLS WERE INCLUDED,HOWEVER, ON THE TAPES. -

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

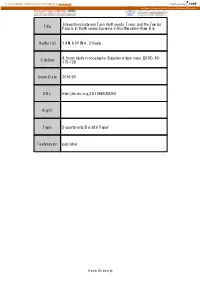

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Threatened Pastures

Himba of Namibia and Angola Threatened pastures ‘All the Himba were born here, next to the river. When the Himba culture is flourishing and distinctive. All Himba cows drink this water they become fat, much more than if are linked by a system of clans. Each person belongs to they drink any other water. The green grass will always two separate clans; the eanda, which is inherited though grow, near the river. Beside the river grow tall trees, and the mother, and the oruzo, which is inherited through the vegetables that we eat. This is how the river feeds us. father. The two serve different purposes; inheritance of This is the work of the river.’ cattle and other movable wealth goes through the Headman Hikuminue Kapika mother’s line, while dwelling place and religious authority go from father to son. The Himba believe in a A self-sufficient people creator God, and to pray to him they ask the help of their The 15,000 Himba people have their home in the ancestors’ spirits. It is the duty of the male head of the borderlands of Namibia and Angola. The country of the oruzo to pray for the welfare of his clan; he prays beside Namibian Himba is Kaoko or Kaokoland, a hot and arid the okuruwo, or sacred fire. Most important events region of 50,000 square kilometres. To the east, rugged involve the okuruwo; even the first drink of milk in the mountains fringe the interior plateau falling toward morning must be preceded by a ritual around the fire.