Examining the Relationship Between the Namibian Government and the Himba of Epupa Falls by Adrian Bradley Borrego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia's Colonization Process

The Immediate and Long-Term Effects of Namibia’s Colonization Process By: Jonathan Baker Honors Capstone Through Professor Taylor Politics of Sub-Saharan Africa Baker, 2 Table of Contents I. Authors Note II. Introduction III. Pre-Colonization IV. Colonization by Germany V. Colonization by South Africa VI. The Struggle for Independence VII. The Decolonization Process VIII. Political Changes- A Reaction to Colonization IX. Immediate Economic Changes Brought on by Independence X. Long Term Political Effects (of Colonization) XI. Long Term Cultural Effects XII. Long Term Economic Effects XIII. Prospects for the Future XIV. Conclusion XV. Bibliography XVI. Appendices Baker, 3 I. Author’s Note I learned such a great deal from this entire honors capstone project, that all the knowledge I have acquired can hardly be covered by what I wrote in these 50 pages. I learned so much more that I was not able to share both about Namibia and myself. I can now claim that I am knowledgeable about nearly all areas of Namibian history and life. I certainly am no expert, but after all of this research I can certainly consider myself reliable. I have never had such an extensive knowledge before of one academic area as a result of a school project. I also learned a lot about myself through this project. I learned how I can motivate myself to work, and I learned how I perform when I have to organize such a long and complicated paper, just to name a couple of things. The strange inability to be able to include everything I learned from doing this project is the reason for some of the more random appendices at the end, as I have a passion for both numbers and trivia. -

Deconstructing Windhoek: the Urban Morphology of a Post-Apartheid City

No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 Working Paper No. 111 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Fatima Friedman August 2000 DECONSTRUCTING WINDHOEK: THE URBAN MORPHOLOGY OF A POST-APARTHEID CITY Contents PREFACE 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 2. WINDHOEK CONTEXTUALISED ....................................................................... 2 2.1 Colonising the City ......................................................................................... 3 2.2 The Apartheid Legacy in an Independent Windhoek ..................................... 7 2.2.1 "People There Don't Even Know What Poverty Is" .............................. 8 2.2.2 "They Have a Different Culture and Lifestyle" ...................................... 10 3. ON SEGREGATION AND EXCLUSION: A WINDHOEK PROBLEMATIC ........ 11 3.1 Re-Segregating Windhoek ............................................................................. 12 3.2 Race vs. Socio-Economics: Two Sides of the Segragation Coin ................... 13 3.3 Problematising De/Segregation ...................................................................... 16 3.3.1 Segregation and the Excluders ............................................................. 16 3.3.2 Segregation and the Excluded: Beyond Desegregation ....................... 17 4. SUBURBANISING WINDHOEK: TOWARDS GREATER INTEGRATION? ....... 19 4.1 The Municipality's -

United States of America–Namibia Relations William a Lindeke*

From confrontation to pragmatic cooperation: United States of America–Namibia relations William A Lindeke* Introduction The United States of America (USA) and the territory and people of present-day Namibia have been in contact for centuries, but not always in a balanced or cooperative fashion. Early contact involved American1 businesses exploiting the natural resources off the Namibian coast, while the 20th Century was dominated by the global interplay of colonial and mandatory business activities and Cold War politics on the one hand, and resistance diplomacy on the other. America was seen by Namibian leaders as the reviled imperialist superpower somehow pulling strings from behind the scenes. Only after Namibia’s independence from South Africa in 1990 did the relationship change to a more balanced one emphasising development, democracy, and sovereign equality. This chapter focuses primarily on the US’s contributions to the relationship. Early history of relations The US has interacted with the territory and population of Namibia for centuries – indeed, since the time of the American Revolution.2 Even before the beginning of the German colonial occupation of German South West Africa, American whaling ships were sailing the waters off Walvis Bay and trading with people at the coast. Later, major US companies were active investors in the fishing (Del Monte and Starkist in pilchards at Walvis Bay) and mining industries (e.g. AMAX and Newmont Mining at Tsumeb Copper, the largest copper mine in Africa at the time). The US was a minor trading and investment partner during German colonial times,3 accounting for perhaps 7% of exports. -

Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W

T 0 ~ume ~-723X)Southern i\fric-a 7, Japuary-wruarv 1997 Southern Africa Network-ELCA 3560 W. Congress Parkway, Chicago, IL 60624 phone (773) 826-4481 fax (773) 533-4728 TEARS, FEARS, AND HOPES: Healing the Memories in South Africa Pastor Philip Knutson of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, reports on a workshop he and other church leaders attended. "The farmer tied my grandfather up to a pole and told him he must get rid of all his cattle.. .! was just a boy then but I will never forget that.. .! could have been a wealthy farmer today if our fam ily had not been dispossessed in that way." The tears streamed down his face as this "coloured" pastor related his most painful experience of the past to a group at a workshop entitled "Exploring Church Unity Within the Context of Healing and Reconciliation" held in Port Elizabeth recently. A black Methodist pastor related his feelings of anger and loss at being deprived of a proper education. Once while holding a service to commemorate the young martyrs ofthe June 1976 Uprising, his con gregation was attacked and assaulted in the church. What hurt most, he said, was that the attacking security forces were black. The workshop, sponsored by the Provincial Council of Churches, was led by Fr. Michael Lapsley, the Anglican priest who lost both hands and an eye in a parcel bomb attack in Harare in 1990. In his new book Partisan and Priest and in his presenta tion he said that every South African has three stories to tell. -

Tourism and Rural Community Development in Namibia: Policy Issues Review

Tourism and rural community development in Namibia: policy issues review ERLING KAVITA AND JARKKO SAARINEN Kavita, Erling & Jarkko Saarinen (2016). Tourism and rural community develop- ment in Namibia: policy issues review. Fennia 194: 1, 79–88. ISSN 1798-5617. During the past decades, the tourism sector has become an increasing important issue for governments and regional agencies searching for socio-economic de- velopment. Especially in the Global South the increasing tourism demand has been seen highly beneficial as evolving tourism can create direct and indirect income and employment effects to the host regions and previously marginalised communities, with potential to aid with the poverty reduction targets. This re- search note reviews the existing policy and planning frameworks in relation to tourism and rural development in Namibia. Especially the policy aims towards rural community development are overviewed with focus on Community-Based Tourism (CBT) initiatives. The research note involves a retrospective review of tourism policies and rural local development initiatives in Namibia where the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) initiated a community-based tour- ism policy. The policy emphasises structures and processes helping local com- munities to benefit from the tourism sector, and the active and coordinating in- volvement of communities, especially, is expected to ensure that the benefits of tourism trickle down to the local level where tourist activities take place. How- ever, it is noted that in addition to public policy-makers also other tourism de- velopers and private business environment in Namibia need to recognize the full potential of rural tourism development in order to meet the created politi- cally driven promises at the policy level. -

Touring Katutura! : Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism In

Universität Potsdam Malte Steinbrink | Michael Buning | Martin Legant | Berenike Schauwinhold | Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA ! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Potsdamer Geographische Praxis Potsdamer Geographische Praxis // 11 Malte Steinbrink|Michael Buning|Martin Legant| Berenike Schauwinhold |Tore Süßenguth TOURING KATUTURA! Poverty, Tourism, and Poverty Tourism in Windhoek, Namibia Universitätsverlag Potsdam Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de/ abrufbar. Universitätsverlag Potsdam 2016 http://verlag.ub.uni-potsdam.de Am Neuen Palais 10, 14469 Potsdam Tel.: +49 (0)331 977 2533 / Fax: -2292 E-Mail: [email protected] Die Schriftenreihe Potsdamer Geographische Praxis wird herausgegeben vom Institut für Geographie der Universität Potsdam. ISSN (print) 2194-1599 ISSN (online) 2194-1602 Das Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Gestaltung: André Kadanik, Berlin Satz: Ute Dolezal Titelfoto: Roman Behrens Druck: docupoint GmbH Magdeburg ISBN 978-3-86956-384-8 Zugleich online veröffentlicht auf dem Publikationsserver der Universität Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-95917 CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 11 1.1 Background of the study: -

Negotiating Meaning and Change in Space and Material Culture: An

NEGOTIATING MEANING AND CHANGE IN SPACE AND MATERIAL CULTURE An ethno-archaeological study among semi-nomadic Himba and Herera herders in north-western Namibia By Margaret Jacobsohn Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town July 1995 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. Figure 1.1. An increasingly common sight in Opuwo, Kunene region. A well known postcard by Namibian photographer TONY PUPKEWITZ ,--------------------------------------·---·------------~ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ideas in this thesis originated in numerous stimulating discussions in the 1980s with colleagues in and out of my field: In particular, I thank my supervisor, Andrew B. Smith, Martin Hall, John Parkington, Royden Yates, Lita Webley, Yvonne Brink and Megan Biesele. Many people helped me in various ways during my years of being a nomad in Namibia: These include Molly Green of Cape Town, Rod and Val Lichtman and the Le Roux family of Windhoek. Special thanks are due to my two translators, Shorty Kasaona, and the late Kaupiti Tjipomba, and to Garth Owen-Smith, who shared with me the good and the bad, as well as his deep knowledge of Kunene and its people. Without these three Namibians, there would be no thesis. Field assistance was given by Tina Coombes and Denny Smith. -

Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: a Mixed Methods Approach

CRITICAL GEOPOLITICS OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT IN NAMIBIA: A MIXED METHODS APPROACH by MEREDITH JOY DEBOOM B.A., University of Iowa, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Geography 2013 This thesis entitled: Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach written by Meredith Joy DeBoom has been approved for the Department of Geography John O’Loughlin, Chair Joe Bryan, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Abstract DeBoom, Meredith Joy (M.A., Geography) Critical Geopolitics of Foreign Involvement in Namibia: A Mixed Methods Approach Thesis directed by Professor John O’Loughlin In May 2011, Namibia’s Minister of Mines and Energy issued a controversial new policy requiring that all future extraction licenses for “strategic” minerals be issued only to state-owned companies. The public debate over this policy reflects rising concerns in southern Africa over who should benefit from globally-significant resources. The goal of this thesis is to apply a critical geopolitics approach to create space for the consideration of Namibian perspectives on this topic, rather than relying on Western geopolitical and political discourses. Using a mixed methods approach, I analyze Namibians’ opinions on foreign involvement, particularly involvement in natural resource extraction, from three sources: China, South Africa, and the United States. -

Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy

CPSXXX10.1177/0010414018758760Comparative Political StudiesLechler and McNamee 758760research-article2018 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Universität München: Elektronischen Publikationen Article Comparative Political Studies 2018, Vol. 51(14) 1858 –1898 Indirect Colonial Rule © The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: Undermines Support for sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018758760DOI: 10.1177/0010414018758760 Democracy: Evidence journals.sagepub.com/home/cps From a Natural Experiment in Namibia Marie Lechler1 and Lachlan McNamee2 Abstract This article identifies indirect and direct colonial rule as causal factors in shaping support for democracy by exploiting a within-country natural experiment in Namibia. Throughout the colonial era, northern Namibia was indirectly ruled through a system of appointed indigenous traditional elites whereas colonial authorities directly ruled southern Namibia. This variation originally stems from where the progressive extension of direct German control was stopped after a rinderpest epidemic in the 1890s, and, thus, constitutes plausibly exogenous within-country variation in the form of colonial rule. Using this spatial discontinuity, we find that individuals in indirectly ruled areas are less likely to support democracy and turnout at elections. We explore potential mechanisms and find suggestive evidence that the greater influence of traditional leaders in indirectly ruled areas has socialized individuals to accept nonelectoral bases of political authority. Keywords indirect colonial rule, decentralized despotism, natural experiment, political attitudes, democratic consolidation, Namibia, democratic institutions, sub- Saharan Africa, spatial RDD 1University of Munich, Germany 2Stanford University, CA, USA Corresponding Author: Marie Lechler, Department of Economics, University of Munich, Schackstraße 4, Munich 80539, Germany. -

Interactions Between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia

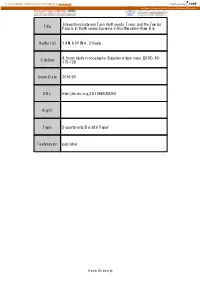

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Interactions between Termite Mounds, Trees, and the Zemba Title People in the Mopane Savanna in Northwestern Namibia Author(s) YAMASHINA, Chisato African study monographs. Supplementary issue (2010), 40: Citation 115-128 Issue Date 2010-03 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/96293 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl.40: 115-128, March 2010 115 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TERMITE MOUNDS, TREES, AND THE ZEMBA PEOPLE IN THE MOPANE SAVANNA IN NORTH- WESTERN NAMIBIA Chisato YAMASHINA Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Termite mounds comprise a significant part of the landscape in northwestern Namibia. The vegetation type in this area is mopane vegetation, a vegetation type unique to southern Africa. In the area where I conducted research, almost all termite mounds coex- isted with trees, of which 80% were mopane. The rate at which trees withered was higher on the termite mounds than outside them, and few saplings, seedlings, or grasses grew on the mounds, indicating that termite mounds could cause trees to wither and suppress the growth of plants. However, even though termite mounds appeared to have a negative impact on veg- etation, they could actually have positive effects on the growth of mopane vegetation. More- over, local people use the soil of termite mounds as construction material, and this utilization may have an effect on vegetation change if they are removing the mounds that are inhospita- ble for the growth of plants. -

Threatened Pastures

Himba of Namibia and Angola Threatened pastures ‘All the Himba were born here, next to the river. When the Himba culture is flourishing and distinctive. All Himba cows drink this water they become fat, much more than if are linked by a system of clans. Each person belongs to they drink any other water. The green grass will always two separate clans; the eanda, which is inherited though grow, near the river. Beside the river grow tall trees, and the mother, and the oruzo, which is inherited through the vegetables that we eat. This is how the river feeds us. father. The two serve different purposes; inheritance of This is the work of the river.’ cattle and other movable wealth goes through the Headman Hikuminue Kapika mother’s line, while dwelling place and religious authority go from father to son. The Himba believe in a A self-sufficient people creator God, and to pray to him they ask the help of their The 15,000 Himba people have their home in the ancestors’ spirits. It is the duty of the male head of the borderlands of Namibia and Angola. The country of the oruzo to pray for the welfare of his clan; he prays beside Namibian Himba is Kaoko or Kaokoland, a hot and arid the okuruwo, or sacred fire. Most important events region of 50,000 square kilometres. To the east, rugged involve the okuruwo; even the first drink of milk in the mountains fringe the interior plateau falling toward morning must be preceded by a ritual around the fire. -

Namibian Influence, Impacts on Education, and State Capture

THE EFFECTS OF COLONIZATION AND APARTHEID ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOUTH AFRICA: NAMIBIAN INFLUENCE, IMPACTS ON EDUCATION, AND STATE CAPTURE by Austin Michael Hutchinson A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Austin Hutchinson All Rights Reserved Abstract When discussing South Africa, apartheid is the most common topic that people remember. The legacies and institutional framework that apartheid established are still prevalent in the current state of development in South Africa. This work examines three prominent issues hindering the development of the South African nation. Understanding the narrative history of colonization and apartheid allows for a more comprehensive view on the current development of South Africa. Using colonial records, court rulings, journals, news articles among various other sources across the topics mentioned, a narrative is created that explains the current problems facing South Africa and Namibia. Namibia endured colonial rule from three different oppressors but was initially claimed by Germany and named German South West Africa. Although Namibia and South Africa were merged under one rule for nearly a century beginning in 1915, each nation had divergent paths to independence. Namibia eventually gained its independence in 1990, a few years prior to South Africa, which gained its own independence from apartheid rule in 1994. As a result of colonization and apartheid in South Africa, certain ideals which hindered the progression of the South African people remained, including inequities in the education system. Furthermore, some of the pervasive systems established under the apartheid regime led to failures in the accountability mechanisms which resulted in institutional weakness and state capture in South Africa.