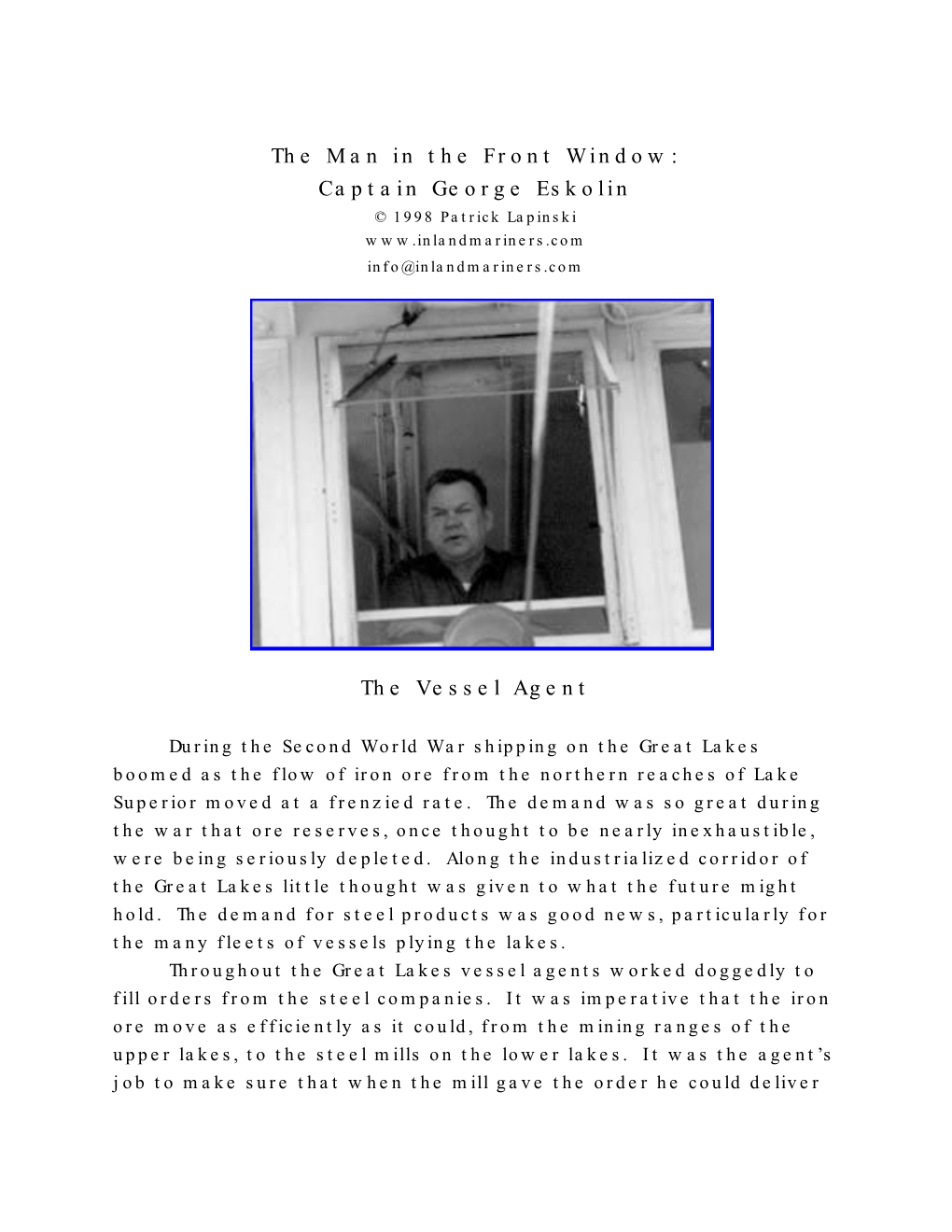

The Man in the Front Window: Captain George Eskolin © 1998 Patrick Lapinski [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lake Seamen's Union, the Lake Carriers' Association, and the Great

An Unequal Clash: The Lake Seamen’s Union, the Lake Carriers’ Association, and the Great Lakes Strike of 1909 Matthew Lawrence Daley La grève des Grands Lacs de 1909 a été le point culminant d’une lutte de plusieurs décennies entre les marins syndiqués et la Lake Carriers’ Association. Les syndicats maritimes s’étaient efforcés de résoudre les problèmes d’identité, d’autorité et de solidarité depuis les années 1870. À la suite d’une défaite face aux travailleurs en 1901, les propriétaires de navires ont transformé leur association informelle en fédération capable de mettre en œuvre des politiques uniformes pour l’ensemble de ses membres. La défaite des travailleurs lors de la grève de 1909 est née de trois grèves précédentes (1901 à 1906); ensemble, ces conflits ont transformé l’industrie des Grands Lacs et permis aux marins de jouer un rôle dans le système industriel désormais transformé en société. The Great Lakes Strike of 1909 drew together all the factors that had been transforming the Lakes maritime industry during the prior two decades and produced a reshaped environment where sailors operated as components within a fully integrated industrial system. The strike stood as a breaking point between two eras, that of the independent and skills-based sailors as defined by sailing ships and small companies, and the corporate world of steel ships and intensive bulk freight commodity transportation. For vessel owners these same changes had shifted the industry into a high-volume, low-margin operation tied to expensive specialized equipment. Understanding the 1909 strike requires reviewing events and decisions that began years earlier. -

Vignettes of Clifton Park I

VIGNETTES OF CLIFTON PARK I Blythe R. Gehring Gehring, Blythe R. Vignettes of Clifton Park. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland State University 2017. ISBN 13: 978-1-936323-38-8 ISBN 10: 1-936323-38-9 This digital edition was prepared by MSL Academic Endeavors, the imprint of the Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University, February 2017. Permission for MSL Academic Endeavors and Cleveland Memory Project to reprint granted by the original rights holder. Clifton Building Company/Stephan Burgyan - 17853 Lake Road - Built in 1900 The house was built in 1900 by the "Clifton Building Company;" Charles W. Root was the first owner. Originally the house was smaller than today. Mr. Root made improvements con sisting of a large kidney-shaped front porch, a larger front entry and a room at the rear of the house which is now the library. When the term hand made is used in the inter view it means that Mr. Burgyan has constructed the items mentioned. Mr. Burgyan has restored the woodwork on the lower floor to its natural oak. It is easy to state this fact but the process was sand blasting in order to remove many layers of paint and the stubborn stain. The motif of the house is gothic. The gothic arch is seen in door panels and the dining room wainscoting. Wherever the gothiC arch fits in appropriately Mr. Burgyan has made paneling, radiator enclosures and book cases in this motif. The front entry has high wainscoting in the restored oak. A hand made wrought iron coat pole has been installed to take the place of the original coat hook method. -

The Degenerate Scion of a Noble Line?

STEAMBOAT JACK: THE DEGENERATE SCION OF A NOBLE LINE? CULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS OF THE AMERICAN SAILOR AND THE MEANING OF MARITIME IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY GREAT LAKES MARITIME WORLD by Dana S. Brown A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2013 © Copyright Dana S. Brown 2013 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The late Christian mystic and philosopher Thomas Merton offered an interesting perspective on cultivating a positive attitude when attempting to accomplish what, at the time, might seem an insurmountable task: Do not depend on the hope of results. You may have to face the fact that your work will be apparently worthless and even achieve no result at all, if not perhaps results opposite to what you expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results, but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. You gradually struggle less and less for an idea and more and more for specific people. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationship that saves everything.1 Although I view this thesis as a personal success I cannot take full credit for it truly could not have happened without the assistance received through personal and professional relationships. While I am wholeheartedly indebted to my thesis committee, Dr. Sandra L. Norman, Dr. Stephen D. Engle, Dr. Kristen Block and Dr. Theodore J. Karamanski Loyola University Chicago, Illinois for their support and guidance throughout the entire research and writing process, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to share ideas, laughs and oftentimes tears, with some very special people. -

GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 TELESCOPE Page 114

SEPTEMBER ☆ OCTOBER, 1989 Volume XXXVII; Number 5 GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 TELESCOPE Page 114 MEMBERSHIP NOTES • Institute member Steve Elve has written Bridging the Waves, Pere Marquette No. 18: Her Final Days. This 32-page book covers the sinking of the PM 18 in Lake Michigan in September, 1910. Although the Coast Guard investigation could not determine the exact cause, Steve provides several possibilities based on researching government records, eye-witness accounts from survivors and marine historians familiar with railferry design. This book is available at the Dossin Museum for $6.00 plus $1.00 postage or from Steve Elve, 11084 Woodbushe Dr., Lowell, MI. 49331. Preservationists are attempting to save two lighthouses in the south channel of Lake St. Clair that were built between 1855 and 1859. In 1875 the front light was rebuilt on the same wooden crib and has remained since, but again is leaning and its base is eroding. The rear light was built on a stone crib with a keeper’s house. The house is gone, but the stone base remains below the water. Those interested in preserving these lights should contact: SOS Channel Lights, P.O. Box 46531, Mt. Clemens, MI. 48046. MEETING NOTICES • Capt. John Leonard will be our guest speaker on Friday, November 17th at 8:00 p.m. at Dossin Museum. Capt. Leonard, retired skipper of the Charles Dick and Chicago Tribune, will show slides of many vessels that have gone to the scrapyard as well as their modem replacements. Future Board of Director meetings (which all members are invited to attend) are scheduled for Thursdays, October 12th and December 14th at 7:30 p.m. -

2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy

2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy 2019 Annual Report To the Community and Report on Philanthropy Cover: Leading UH research on COVID-19, Grace McComsey, MD, Vice President of Research and Associate Chief Scientific Officer, UH Clinical Research Center, Rainbow Babies & Children's Foundation John Kennell Chair of Excellence in Pediatrics, and Division Chief of Infectious Diseases, UH Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital; and Robert Salata, MD, Chairman, Department of Medicine, STERIS Chair of Excellence in Medicine and and Master Clinician in Infectious Disease, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and Program Director, UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine and Global Health, are Advancing the Science of Health and the Art of Compassion. Photo by Roger Mastroianni The 2019 UH Annual Report to the Community and Report on Philanthropy includes photographs obtained before Ohio's statewide COVID-19 mask mandate. INTRODUCTION REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY 5 Letter to Friends 38 Letter to our Supporters 6 UH Statistics 39 A Gift for the Children 8 UH Recognition 40 Honoring the Philanthropic Spirit 41 Samuel Mather Society UH VISION IN ACTION 42 Benefactor Society 10 Building the Future of Health Care 43 Revolutionizing Men's Health 12 Defining the Future of Heart and Vascular Care 44 Improving Global Health 14 A Healing Environment for Children with Cancer 45 A New Game Plan for Sports Medicine 16 UH Community Highlights 48 2019 Endowed Positions 18 Expanding the Impact of Integrative Health 54 Annual Society 19 Beating Cancer with UH Seidman 62 Paying It Forward 20 UH Nurses: Advancing and Evolving Patient Care 63 Diamond Legacy Society 22 Taking Care of the Browns. -

Report to the Community 2009Community the to Report Bigpicture T H E We See The

THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION Report to the Community 2009 THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION 1422 Euclid Avenue Suite 1300 Cleveland, Ohio 44115 216.861.3810 www.ClevelandFoundation.org Report to the Community We see the 2009 big picture CONTENTS 2 CEO and Chairman’s Letter 2 8 Grantmaking Highlights 7 CEO Perspective 3 0 New Gifts Vital Issues 3 4 Donor Societies and Funds 8 Economic Development 3 8 Financial Summary Staff 1 2 Education 3 9 Committees and Banks 1 6 Human Services and Youth Development 4 0 Board of Directors and Staff 95 Cleveland Foundation Ciba Jones Linda Puffenberger Suite 1300 2 0 Neighborhoods PROGRAM ASSISTANT FINANCIAL ANALYST 1914 – 2009 Suite 1300 Services is an 2 4 Arts and Culture Executive Office Mary J. Clink Sarah L. King affiliate of the Cleveland Ronald B. Richard 1,2 PROGRAM ASSISTANT ASSISTANT CONTROLLER PRESIDENT & CEO Foundation that provides Harold J. Garling Jr. Tammi Amata Jennifer A. Teeter PROJECT AccESS ASSISTANT AccoUNTING MaNAGER support services to emerging EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT nonprofits. Charlotte J. Morosko Dorothy M. Highsmith Program, Grants GRANTS ADMINISTRATOR SENIOR AccoUNTANT Leslie A. Dunford Management, and Records Karen Bartrum-Jansen Ya-Mei Chen EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR FUND AccoUNTANT Robert E. Eckardt 1,2 GRANTS ASSISTANT Jean A. Lang SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT FOR Judith A. Corey Carol A. Hellyar STAFF AccoUNTANT PROGRAMS AND EVALUATION FUND AccoUNTANT GRANTS ASSISTANT Lisa L. Bottoms Christine M. Lawson Civic Innovation Lab ENDOWMENT GRANTMAKING PROGRAM DIRECTOR FOR HUMAN Denise G. Ulloa FINANCE ASSocIATE SERVICES AND CHILD AND YOUTH GRANTS ASSISTANT Jennifer Thomas Total Assets (dollars in billions) Total Grants (dollars in millions) MISSION DEVELopMENT Carmela Beltrante PROGRAM DIRECTOR Patty A. -

Testimony. in Re the Livingstone Channel

INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION TESTIMONY. IN RE THE LIVINGSTONE CHANNEL ON THE REFERENCEOF THE GOVERNMENTSOF THE UNITED STATES AND THE DOMINION OF CANADA UNDER ARTICLE IX OF THE TREATY OF FAY 5, 1910 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1913 INTERNATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION. UNITEDSTATES. CANADA. 3AMES A. TAWNEY, Chairman. TH. CHASE CASGRAIN?Chairman. FRANK S. STREETER. HENRY A. POWELL. GEORGE TURNER. CHARLES A. MAGRATH. L. WHITEBVSBEY, Secretary. LAWRENCEJ. BURPEE,Secretary. 2 QUESTIONS REFERRED, “1. Under all the circumstances and conditions surrounding the navigation and other uses of the Livingstone and other channels in the Detroit River on either side of the international boundary, is the erection of any dike or other compensatory work deemed necessary or desirable for the improvement or safety of navlgation at or in the vicinityof Bois Blanc Island inconnection with rock excavation and dredg- ing in Livingstone Channel authorized by the rivers and harbors act of June 25,1910 (36 Stats., 655), and described in House Document No. 676, Sixty-first Congress, second session, sundry civil actof June 25, 1910 (36 Stats., 729), sundry civil actof March 4, 1911 (36 Stats., 1405), of the United States, andnow being carried out by theGovern- mytof the United States? 2. If in answer to question 1 any dike or other compensatory works are found to be necessary or desirable, will the work or works proposed by the United States and provided for in therivers and harbors actofJune 25,1910 (36 Stats., 655),and located 80 as to connect thenorth end of Bois Blanc Island to the southeast end of the existing cofferdam on the east side of Livingstone Channel o posite and below Stoney Island, be sufficient for the purpose; and if not what adgtional or other dikes or compen- satory works should be constructed and where should they be located in order to serve most advantageously the interests involved on both sides of the international boundary? ” 3 THE LIVINGSTONE CHANNEL. -

The Cleveland Foundation and Its Evolving Urban Strategy

Rebuilding Cleveland is a critical study of the role that The Cleveland Foundation, the country's oldest community trust, has played in shaping public affairs in Cleveland, Ohio, over the past quarter-century. Drawing on an examination of the Foun dation's private papers and more than a hun dred interviews with Foundation personnel and grantees, Diana Tittle demonstrates that The Cleveland Foundation, with assets of more than $600 million, has provided con tinuing, catalytic leadership in its attempts to solve a wide range of Cleveland's urban problems. The Foundation's influence is more than a matter of money, Tittle shows. The combined efforts of professional philanthro pists and a board of trustees traditionally dominated by Cleveland's business elite, but also including members appointed by var ious elected officials, have produced innova tive civic leadership that neither group was able to achieve on its own. Through an examination of the Founda tion's ongoing and sometimes painful orga nizational development, Tittle explains how the Foundation came to be an important ca talyst for progressive change in Cleveland. Rebuilding Cleveland takes the reader back to 1914, when Cleveland banker Frederick C. Goff invented the concept of a community foundation and pioneered a national move ment of social scientists, business leaders, and government officials that made philan thropy a more effective force for private in volvement in public affairs. Tittle follows the Foundation through the 1960s, when it be gan a major new initiative to establish itself REBUILDING CLEVELAND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES ON BUSINESS ENTERPRISE SERIES Manse/ G. Blackford and K. -

Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht

Cleveland Landmarks Commission Cleveland Architects Herman Albrecht Birth/Established: March 26, 1885 Death/Disolved: January 9, 1961 Biography: Herman Albrecht worked as a draftsman for the firm of Howell & Thomas. He formed the firm of Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly 1918 with Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. Herman Albrecht was a native of Massillon. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon and was responsible for 700 commissions that are found in Cleveland suburbs of Lakewood, Rocky River, Shaker Heights; and in Massillon, Canton, Alliance, Dover, New Philadelphia, Mansfield, Wooster, Alliance and Warren, Ohio. Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly Birth/Established: 1918 Death/Disolved: 1925 Biography: The firm Albrecht, Wilhelm & Kelly was formed in 1918 with Herman Albrecht of Cleveland, Karl Wilhelm of Massillon and John S. Kelly of Cleveland. John Kelly left the firm in 1925 and it was knwon Albrecht & Wilhelm from 1925 until 1933. It was later known Albrecht, Wilhelm, Nosek & Frazen. The firm, which maintained offices in both Cleveland and Massillon. Building List Structure Date Address City State Status Koch Building unk Alliance OH Quinn Residence 1925 Canton OH Standing T.K. Harris Residence 1926 Canton OH Standing William H. Pacell Residence 1919 Alliance OH Standing Meyer Altschuld Birth/Established: 1879 Death/Disolved: unknown Biography: Meyer Altschuld was Polish-born, Yiddish speaking, and came to the United States in 1904. He was active as a Cleveland architect from 1914 to 1951. -

Document (PDF)

TELESCOPE May- June, 1968 Volume 17, Number 5 e KEJ i Great Lakes Maritime Institute Dossin Great Lakes Museum, Belle Isle, Detroit 7, Michigan MAY-JUNE Page A94 FLOUR by C. E. Stein STORY Twelve days after the ore carrier As long ago as September of 1848 DANIEL J. MORRELL foundered in Lake close to three hundred barrels of Huron during the early morning flour and corn meal were salvaged hours of November 29» 1966, the along the Ontario deaches of Lake Huron. In October of the same year body of one of her deckhands, that of Saverio Grippe of Ashtabula, the charred upper works of the pro pellor GOLIAH were discovered near Ohio, was found washed up on the beach of Inverhuron Point, nine the mouth of the Pine River. Her mites north of Kincardine, Ontario. mast floated ashore at Kincardine. According to Mansfield,the GOLIAH One day later, Howard Trussler of had cleared the St. Clair River, up Point Clark picked up a life pre bound on Septmber 13, 1848 with a server and a flare container from the MORRELL which he had found on very heavy cargo consisting of 200 the beach south of Kincardine, at kegs of powder, 20,000 bricks, 30, 000 feet of lumber, 40 tons of hay, the mouth of the Pine River. and 2,000 kegs and barrels of pro One month later, Alex Ritchie and visions and flour consigned to var Constable Bernard Ashton of South ious mining companies along Lake hampton, Ontario discovered in the Superior. Three hours later the schooner SPARTA followed the GOLIAH shore ice south of that port, a mattress, a mans shoe, a small sec up into Lake Huron within sight of tion of a life boat, and an oar. -

Captain Mitch

Captain Mitch Guard us oh god, almighty king, From Gale of Fall, oh keep us safe. From Shoal and Reef, protect us from The Inland Seas. To Long Ships passing through the night, Please give the guidance of thy light. The following tribute was written with the help and cooperation of the shipmates and colleagues of Captain Hallin. It was a chilly spring morning as the M/V Paul R. Tregurtha cleared De Tour downbound into a windswept Lake Huron. A southwest course was ordered in response to the deteriorating weather conditions. First Mate Mike La Combe glanced at his watch, its minute hand moving closer to the top of the hour when a master’s salute, customarily given to in respect to the master of a passing vessel, would be given in honor of the memory of the Tregurtha’s longtime skipper, Captain Mitch Hallin. Fifteen minutes into their southwest course the giant air horns on the Paul R. Tregurtha sounded the salute, fittingly to a hori- zon void of any passing ship. That same morning in Superior, Wisconsin, over a day’s sailing time from De Tour, and regular port of call for the Paul R. Tregurtha, Interlake Steamship Company port representative Kevin Alway stepped onto the Elton Hoyt 2nd where he had readied an air compressor to sound the ship’s long silent whistle. At precisely 9 a.m. on the morning of Friday, May 10 Alway pressed the lever from the pilothouse of the Hoyt, sounding a long and heartfelt Master’s salute that carried down the harbor’s East Basin toward the hills of Duluth. -

GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE .> DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 TELESCOPE Page 86

JULY ☆ AUGUST, 1987 Volume XXXVI; Number 4 GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE .> DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 TELESCOPE Page 86 MEMBERSHIP NOTES • In the March issue we listed all the back issues of Telescope that were available. The demand for these has been higher them expected and a few issues are no longer available. As of July 1st, the following issues are available for $1.00 each. 1976-March, 1977-none, 1978-Jan., Mar., 1979-Jan., Mar., May 1980-none, 1981-Nov., 1982-Jan., May, Nov., 1983-Jan., Mar., May, Oct., 1984-1985-1986 - all issues. To update the book list, The Northern Lights by Hyde is out of print. The publisher plans to have another printing available for Christmas, 1987. Institute member Lawrence Brough has published Autos On The Water, a history of the McCarthy and Nicholson auto carriers that sailed on the lakes until the 1960’s. The photos alone are worth the $8.95 price. Members can order the book through the museum and please add $1.50 for UPS postage for a single copy. Institute member Rene Beauchamp is offering an Index of Seaway Ocean Vessels, 1986. It is an interesting list of vessels that have entered the Seaway and it’s presented in book form in 25 pages. The listing includes country of registry, gross tonnage and other information such as renames. To order contact: Rene Beauchamp, 9041 Bellerive, Montreal, Quebec Canada H 1L 3S5. The price is $4.00 U.S. and includes postage. MEETING NOTICES • There are no meetings in July.