Flying Fortress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page Key to Index

PAGE KEY TO INDEX AIRCRAFT — B-17 "Flying Fortresses" 1 AIRCRAFT — Other 2 AWARDS — Military 2 AWARDS —Other 3 CITIES 3 ESCAPES and EVASIONS 10 GENERAL 10 INTERNEES 19 KILLED IN ACTION 19 MEMORIALS and CEMETERIES 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — 303rd BG 20 MILITARY ORGANIZATIONS — Other 21 MISSIONS — Target and Date 25 PERSONS 26 PRISONERS OF WAR 51 REUNIONS 51 WRITERS 52 1 El Screamo (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Miss Lace (Feb. 2004, pg. 18), (May 2004, Fast Worker II (May 2005, pg. 12) pg. 15) + (May 2005, pg. 12), (Nov. 2005, I N D E X FDR (May 2004, pg. 17) pg. 8) + (Nov. 2006, pg. 13) + (May 2007, FDR's Potato Peeler Kids (Feb. 2002, pg. pg. 16-photo) 15) + (May 2004, pg. 17) Miss Liberty (Aug. 2006, pg. 17) Flak Wolf (Aug. 2005, pg. 5), (Nov. 2005, Miss Umbriago (Aug 2003, pg. 15) AIRCRAFT pg. 18) Mugger, The (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flak Wolf II (May 2004, pg. 7) My Darling (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) B-17 "Flying Fortress" Floose (May 2004, pg. 4, 6-photo) Myasis Dragon (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bison (Nov. 2006, pg. 19-photo) Nero (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) Flying Bitch (Aug. 2002, pg. 17) + (Feb. Neva, The Silver Lady (May 2005, pg. 15), “451" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) 2004, pg. 18) (Aug. 2005, pg. 19) “546" (Feb. 2002, pg. 17) Fox for the F (Nov. 2004, pg. 7) Nine-O-Nine (May 2005, pg. 20) + (May 41-24577 (May 2002, pg. 12) Full House (Feb. 2004, pg. 18) 2007, pg. 20-photo) 41-24603 (Aug. -

Jul-2000 OCR Optimize.Pdf

July 2000 385th BGMA Newsletter_____________________________Page 2 President's Report Hi! By the time you receive this copy of the Hardlife Herald the tour group will have returned from our trip to Great Ashfield, I am writing this on Memorial weekend so it will be along that Paris and Perle Luxembourg. Now our next big plans are for theme. the reunion to be held next year in April, 4-8 in Albuquerque, NM. Make your plans now to attend and mark the dates My brother, Dr. R.E. Vance, Jr. is a retired History Professor down on your calendar. Hal Goetsch our Albuquerque host and he wrote me about their local historical society’s meet is going all out to make this reunion one that you will remem ing. It featured six people that gave personal experiences ber. A great program is being planned that will be enjoyed by about the home front during World War II. Russ, my brother, all. was in the army during the war but he had written a book in 1976 on the history of the University in Pennsylvania. In his It seems there is more mention of W.W.II lately than there speech he described the cadet nurses program. One of the was for many years with the Washington D.C. memorial in young nurses told how she had enjoyed hearing the program the making and the opening in June of the museum in New described because she had been in the program. My brother Orleans. The author Stephen Ambrose has spearheaded the asked her if she was in a combat area. -

Remember Me? Report on the Submitted by Robert R

Vol. 30, No. 1 SECOND AIR DIVISION ASSOCIATION Spring 1991 Report on the Remember Me? Trust Submitted by Robert R. Starr Memorial by E.(Bud) Koorndyk The essence of this report will be of a nature of sharing with you, the supporters of our trust, the enthusiasm shown by our wonderful friends in Norwich who so carefully nurture the fond memories of our associations with them during the trying days of World War II and have carried that through in helping us to maintain our wonderful Memorial Library and the trust that administers it. As I reported at our convention in Nor- wich last summer, the University of East Anglia had anticipated spending a day at our Memorial Library and at a City Hall reception, with over 100 American students attending the University. Professor Howard Temperly of the University and also a member of our Board of Governors, ar- but whatever Some people call me Old Glory, others call me the Star Spangled Banner, ranged this day's activities. The upshot of Something they call me, I am still your Flag, the Flag of the United States of America ... the matter was our learning that the it is about you has been bothering me, so I thought I might talk it over with you. .. because American students had no idea of the role and me. we played in World War II. The library and to watch the parade I remember some time ago people lined up on both sides of the street its educational data astounded them. Isn't breeze. -

Marinell a Combat Veteran P-51D Mustang LL WARBIRD Restorations Are Worthy of Praise, but Every Once in a While Something Pops up That Makes You Raise Your Eyebrows

SPECIAL RESOURCE SECTION www.warbirddigest.com RESTORATION FACILITIES & AVIATION PARTS COMPANIES The Flying Finn PBY GoesPBY Dutch Friends of Jenny MILITARY AVIATION MUSEUM Biplanes & Triplanes 2014 Marinell A Combat Veteran P-51D Mustang LL WARBIRD restorations are worthy of praise, but every once in a while something pops up that makes you raise your eyebrows. During A the summer of 2014 a newly restored Hawker Hurricane emerged from the workshop of Phoenix Aero Services at Thruxton Airport, U.K., after a 12- year restoration. There are approximately 13 Hurricanes flying around the world today, so why is this one so special? Well, besides being very carefully rebuilt, it The Flying is unusual in that it carries the colors and markings of a Hurricane of the World War Two Finnish Air Force. The Man Behind the Restoration The owner of this Hurricane project is Phillip surest ways to get it done.” The Hurricane is his Lawton, a very positive and generous gentleman. first step into historic aviation. Previous aviation He has an engineering background and ran a related experience involved touring aircraft and Story and Photography by Bjorn Hellenius successful company in the hydraulic and water modern aerobatic machines and he used to fly pump business together with his brother for many displays with an Extra 300. Before learning to fly Finn years. He decided to retire at 50, and the sale of his he also built plastic and radio controlled models. (main-photo) The basis of this fabulous Finnish Hur- business provided the funds to get involved in the “I still build plastic models for my children as well ricane was a Canadian Car & Foundry built Mk.XII Warbird industry. -

Consolidated B-24 Liberator USER MANUAL

Consolidated B-24 Liberator USER MANUAL Virtavia Consolidated B-24 Liberator Manual Version DTG 1.0 0 Introduction The Consolidated B-24 Liberator became a major player for Allied forces during World War 2. Its exploits ranged the world over - as did her users- and she saw action in a variety of roles in all major theatres. Designed to overtake the mythical Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and appearing as a more modern design in 1941, the Liberator fell short of this goal but instead operated side-by-side with her contemporary to form a powerful hammer in the hand of the Allied bombing effort. Though the B-17 ultimately proved the favourable mount of airmen and strategic personnel, one cannot doubt her impact in the various roles she was assigned to play in. The Liberator went on to become the most produced American aircraft of the entire war. Virtavia Consolidated B-24 Liberator Manual Version DTG 1.0 1 Credits Model, animations, manual – Virtavia Textures – Dan Dunn of Pixl Creative Gauges – Herbert Pralle/Virtavia Flight Dynamics - Mitch London Engine Sounds - TSS Testing - Frank Safranek, Mitch London Virtavia Consolidated B-24 Liberator Manual Version DTG 1.0 2 Support Should you experience difficulties or require extra information about the Virtavia B-24 Liberator, please e-mail our technical support on [email protected] Copyright Information Please help us provide you with more top quality flight simulator models like this one by NOT using pirate copies. The flight simulation industry is not very profitable and we need all the help we can get. -

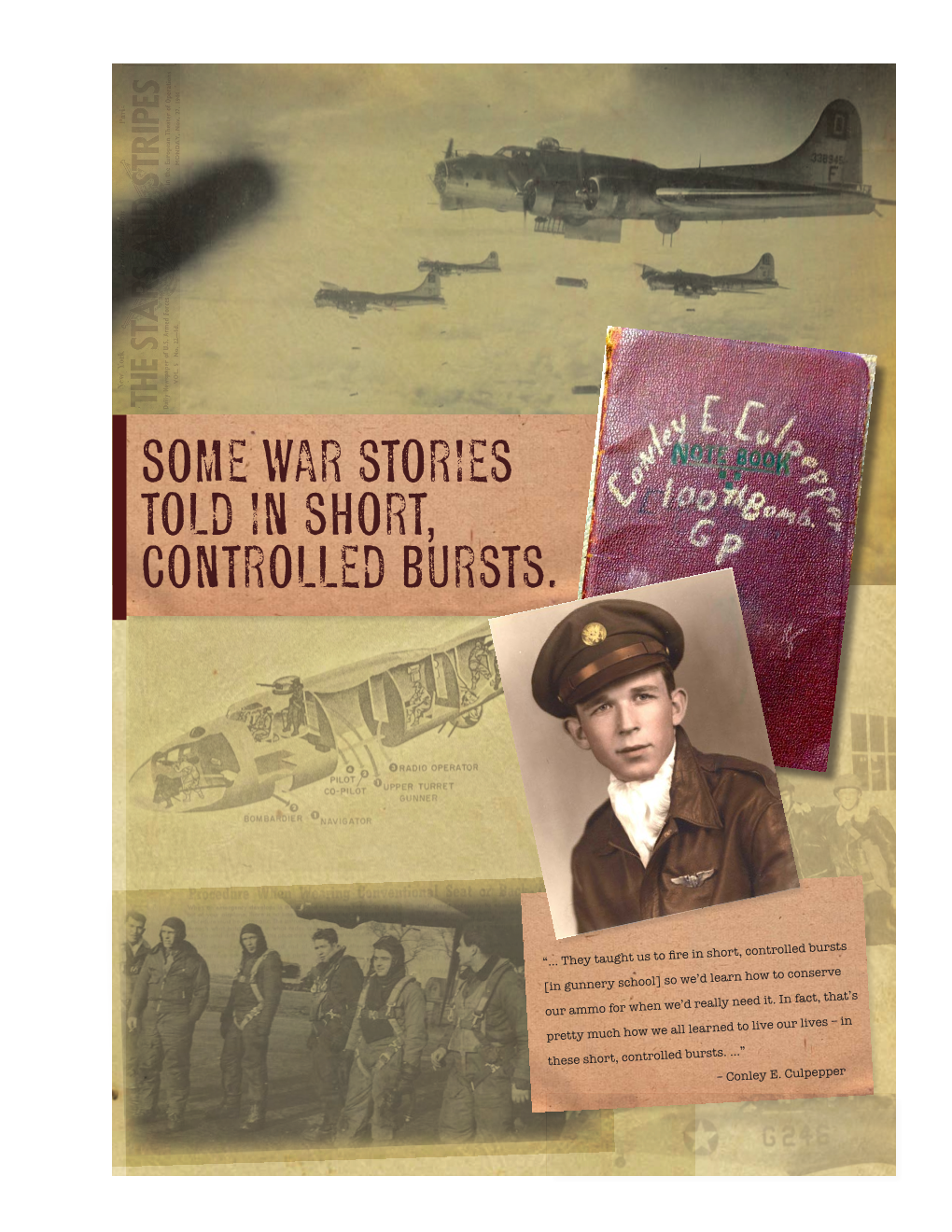

Aerial Gunner Training

Aerial Gunner Training As captivating as are the combat stories of America’s World War II aerial gunners, so too is the wartime history of the training program that produced them. Some of the earliest training methods devised in 1941 were crude and laughable, and hardly effectual. But ongoing efforts to improve the program led to the development of ingenious ideas, complex Future gunners review the inner workings of theories, hi-tech innovations, and fascinating the Browning .30 caliber machine gun. failures. The U.S. Army Air Force’s plans for a flexible gunnery training program were progressing at a leisurely pace during the latter months of 1941. Construction of three gunnery schools was nearing completion and the first instructor class had graduated. But overnight, the declarations of war against Germany and Japan created an urgent need for large scale training. There were enormous obstacles to meeting such a demand. Training men for the unique physical Students are being timed as they strip and and mental demands of being an aerial gunner then reassemble .50 caliber machine guns blindfolded. was very complex. America had no experience to draw on, and only a handful of newly trained instructors were available. There were not enough planes, equipment and ordnance to fight the war, let alone enough to supply the schools. Nevertheless the first Air Force flexible gunnery classes were in session just days after Pearl Harbor. Las Vegas Army Airfield, the first of the new flexible gunnery schools began accepting its first students in December 1941. Two more Students are trained in disassembling and reassembling their machine guns schools at Harlingen Airfield, Texas, and blindfolded. -

Heroic Tale of a Tail Gunner

Heroic Tale of a Tail Gunner By Robert Porter Lynch I thought I'd better write this story before it slips into lost and forgotten stories of WWII heroics...... Twenty five years ago (1989) my wife and I owned and operated the Saxton's River Inn in Vermont. It was built at the turn of the century. We had an old Victorian style bar. Every afternoon about 4 pm the locals would wander in and tell colorful stories, During wartime operation, the crew of a B-17 mostly mundane, many idiosyncratic (we consisted of four officers were responsible for had some very unique old Yankees in town), and sometimes a truly memorable offense (pilot, copilot, bombardier, and story would be told. This is the one I navigator) plus six enlisted men who operated remember most vividly: the defensive guns and radio. Dick Abbott lived several miles away, 1. The average age of an Eighth Air Force bomber toward Grafton. At the time he was in his crew in Europe was 22, and the unfortunate truth mid-sixties (and has subsequently passed was that their life expectancy in 1943 and 1944 away). He was a very mechanical guy and had was only 12 to 15 missions. just retired from being an engineer; we often traded stories about cars. his son and he had Because of the high attrition rate, there was a raced stock cars. Dick was also very high likelihood of being captured. Every enlisted mechanical, and could fix just about anything. man, regardless of earned rank, wore the Not a man to tell tall-tales, Dick was generally uniform of a sergeant. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide Volume 2: Air and Air Defense Systems

Dec Worldwide Equipment Guide 2016 Worldwide Equipment Guide Volume 2: Air and Air Defense Systems TRADOC G-2 ACE–Threats Integration Ft. Leavenworth, KS Distribution Statement: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 1 UNCLASSIFIED Worldwide Equipment Guide Opposing Force: Worldwide Equipment Guide Chapters Volume 2 Volume 2 Air and Air Defense Systems Volume 2 Signature Letter Volume 2 TOC and Introduction Volume 2 Tier Tables – Fixed Wing, Rotary Wing, UAVs, Air Defense Chapter 1 Fixed Wing Aviation Chapter 2 Rotary Wing Aviation Chapter 3 UAVs Chapter 4 Aviation Countermeasures, Upgrades, Emerging Technology Chapter 5 Unconventional and SPF Arial Systems Chapter 6 Theatre Missiles Chapter 7 Air Defense Systems 2 UNCLASSIFIED Worldwide Equipment Guide Units of Measure The following example symbols and abbreviations are used in this guide. Unit of Measure Parameter (°) degrees (of slope/gradient, elevation, traverse, etc.) GHz gigahertz—frequency (GHz = 1 billion hertz) hp horsepower (kWx1.341 = hp) Hz hertz—unit of frequency kg kilogram(s) (2.2 lb.) kg/cm2 kg per square centimeter—pressure km kilometer(s) km/h km per hour kt knot—speed. 1 kt = 1 nautical mile (nm) per hr. kW kilowatt(s) (1 kW = 1,000 watts) liters liters—liquid measurement (1 gal. = 3.785 liters) m meter(s)—if over 1 meter use meters; if under use mm m3 cubic meter(s) m3/hr cubic meters per hour—earth moving capacity m/hr meters per hour—operating speed (earth moving) MHz megahertz—frequency (MHz = 1 million hertz) mach mach + (factor) —aircraft velocity (average 1062 km/h) mil milliradian, radial measure (360° = 6400 mils, 6000 Russian) min minute(s) mm millimeter(s) m/s meters per second—velocity mt metric ton(s) (mt = 1,000 kg) nm nautical mile = 6076 ft (1.152 miles or 1.86 km) rd/min rounds per minute—rate of fire RHAe rolled homogeneous armor (equivalent) shp shaft horsepower—helicopter engines (kWx1.341 = shp) µm micron/micrometer—wavelength for lasers, etc. -

Hitting Home the Air Offensive Against Japan

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan Daniel L. Haulman AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1999 Hitting Home The Air Offensive Against Japan The strategic bombardment of Japan during World War II remains one of the most controversial subjects of military history because it involved the first and only use of atomic weapons in war. It also raised the question of whether strategic bombing alone can win wars, a question that dominated U.S. Air Force thinking for a generation. Without question, the strategic bombing of Japan contributed very heavily to the Japanese decision to surrender. The United States and her allies did not have to invade the home islands, an invasion that would have cost many thousands of lives on both sides. This pamphlet traces the development of the bombing of the Japan- ese home islands, from the modest but dramatic Doolittle raid on Tokyo in April 1942, through the effort to bomb from bases in China that were supplied by airlift over the Himalayas, to the huge 500-plane raids from the Marianas in the Pacific. The campaign changed from precision daylight bombing to night incendiary bombing of Japanese cities and ultimately to the use of atomic bombs against Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story covers the debut of the spectacular B–29 air- craft—in many ways the most awesome weapon of World War II— and its use not only as a bomber but also as a mine-layer. Hitting Home is the sequel to High Road to Tokyo Bay, a pamphlet by the same author that concentrated on Army Air Forces’ tactical op- erations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II. -

384Th Bomb Group, Inc. News & Journal

384th Bomb Group, Inc. News & Journal “Keep The Show On The Road...” June 2019 England Junket XI Reunion Anticipation Builds As you read this, most likely Junket XI reunion attendees will be either on their way to Cambridge, England or are already there. From talking to some of them, and seeing the online posts of others, I know that there is a great deal of anticipation and excitement for the trip on both sides of the Atlantic. A significant number of the attendees have never been to Grafton Underwood, so it will have an even greater impact on them. I remember my first visit to Grafton Underwood; the smell of the woods, the wind in the trees, the soft rain, the quiet anticipation. The place is dense with stories and lives past. It whispers to you. And the impact of it has never really left me. I’m sure it will be the same for them as well and will sustain them in their devotion to the Group in the years to come. For our attending Veterans, it will bring back memories of friends, the stories, their youth, the hard work of the missions and their homecoming when their missions had been completed. For the folks in Grafton Underwood, they may as excited, if not more, as the attendees are about the visit. The anticipation for them is high. They have been very busy working to clean, repair, and prepare the Monument and area for a very memorable experience. They’ll have special information about their new non-profit organization, Friends of The 384th. -

January & February 2019

Volume XXV, Issue 1 January/February 2019 Hangar Tales Official Newsletter of the National Warplane Museum Inside the Hangars Dick Ash - In Memorium The Fix-it Man - “Super Dave” 2018 Air Shows - the Year in Review A “VIP” Flight Collections P a g e 2 Hangar Tales Dick Ash Aviator, Benefactor, Friend On January 11, 2019, the National Warplane Museum lost a great friend and benefactor with the passing of Dick Ash. Dick was CEO of Livingston Associates (CP Ward) and was on the Board of Directors for the NWM and the Genesee Country Village and Museum. Dick was predeceased by his wife, Joan. He is survived by two daughters, Catherine (David) Strong and Jennifer (Brian) Geer, and two grandchildren, Peytyn and Parker Geer. Aviator Dick worked hard all his life and aviation became his outlet. A commercially rated pilot, Dick discovered his love of flying when he was invited by a friend, Craig Johnston, to accompany him on a trip to NJ in the late 70’s. Bitten by the flying bug, he started lessons at the LeRoy airport and eventually received his pilot’s license. Needing something to fly, he became co-owner of a Cessna 172 with Craig. This eventually led to the purchase of a single engine Beechcraft Bonanza that Dick used traveling to Florida to manage projects that CP Ward was involved in there. Losing electrical power on one (or several) of his flights, he de- cided a twin engine aircraft was the way to go, so he upgraded to Dick in the Left seat of “Whiskey 7” a Beechcraft Baron. -

Experimental Aircraft Association Chapter 105 Portland, OR

122.75 HELP J. Rion Bourgeois, Chapter President NEEDED B-17 Visit Scratched Our June will not be so busy after all. The land- at the ing gear on the Aluminum Overcast collapsed on roll-out at Van Nuys Airport last month, and she RV will not be repaired in time to complete her tour FLY-IN! this year. Call Marcy Lange (503-397-2488 hm. eves, 503-397-1478 June Meeting Third Thursday This Month, wk. days or e-mail: [email protected]) if you can help July Meeting Second Friday Next Month with the food for the RV Fly-In June 19th. Mostly I just Please note that the June meeting at Ken Scottʹs house on Dietz need help that day, and I’m not particular about gender Airpark is the THIRD Thursday of the month this month on June help, men or women, any help will be appreciated. Also, 17. The project is Ken and Ken Kruegerʹs Pipsqueak project. For Harmon Lange is heading up the Set Up committee and those looking ahead, the July meeting is Friday, July 9 at 7 pm at needs help. You can call him anytime at 503-397-1478 or Experimental Mike Wilsonʹs tent at Arlington. BYOB and chair, but there will be e-mail: [email protected] Aircraft finger food. Young Eagles at Scappoose In This Issue Association We will be giving Young Eagles flights to the ACE Campers from 122.75..................................................................................................1 the Airways Sciences Center summer camp during the fly-in at N6810B’s First Flight ........................................................................2 Scappoose on June 19, 2004.