Supplement Roger Collicott Catalogue 99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4.0 Appraisal of Special Interest

4.0 APPRAISAL OF SPECIAL INTEREST 4.1 Character Areas Botallack The history and site of Botallack Manor is critical to an understanding of the history and development of the area. It stands at the gateway between the village and the Botallack mines, which underlay the wealth of the manor, and were the reason for the village’s growth. The mines are clearly visible from the manor, which significantly stands on raised ground above the valley to the south. Botallack Manor House remains the single most important building in the area (listed II*). Dated 1665, it may well be earlier in some parts and, indeed, is shown on 19th century maps as larger – there are still 17th century moulded archway stones to be found in the abandoned cottage enclosure south of the manor house. The adjoining long range to the north also has 17th century origins. The complex stands in a yard bounded by a well built wall of dressed stone that forms a strong line along the road. The later detached farm buildings slightly to the east are a good quality 18th/19th century group, and the whole collection points to the high early status of the site, but also to its relative decline from ‘manorial’ centre to just one of the many Boscawen holdings in the area from the early 19th century. To the south of Botallack Manor the village stretches away down the hill. On the skyline to the south is St Just, particularly prominent are the large Methodist chapel and the Church, and there is an optical illusion of Botallack and St Just having no countryside between them, perhaps symbolic of their historical relationship. -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

The London Gazette, 29Th September 1982 12663

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 29TH SEPTEMBER 1982 12663 virtue of The Secretary of State for Trade and Industry Order, In the Plymouth County Court, No. 75 of 1975 1970) removing Matthew Charles ELLIS of Maxwell In Bankruptcy House, 167 Armada Way, Plymouth, Devon, PL11JH from the office of Trustee of the property of the said Cecil Champion, Re. HUMBY, Terence Raymond, of 90 Looseleigh Lane, a Bankrupt. Crownhill, Plymouth, Devon, COMPANY DIRECTOR. A.K. Sales, Principal Examiner Notice is hereby given, that an Order was, on the 12th day of An authorised Officer of the Department of Trade August 1982 made by the Secretary of State in exercise of-his 24th September 1982. powers under the Bankruptcy Acts, 1914 and 1926 (as having effect by virtue of The Secretary of State for Trade and Industry Order, 1970) removing Matthew Charles ELLIS of Maxwell House, 167 Armada Way, Plymouth, Devon, PL1 1JH from In the Truro and Falmouth County Court, No. 4 of 1976 the office of Trustee of the property of the said Terence Raymond In Bankruptcy Humby, a bankrupt. A.K. Sales, Principal Examiner Re. DAVEY, Philip George, previously trading as P G Davey An authorised Officer of the Department of Trade (BUILDER and CONTRACTOR) now unemployed of 24th September 1982. Carnyorth, St Just, Near Penzance in the county of Cornwall. Notice is hereby given, that an Order was, on the 12th day of August 1982 made by the Secretary of State in exercise of his In the Truro County Court (By transfer from the High powers under the Bankruptcy Acts, 1914 and 1926 (as having Court of Justice). -

The Cornish Mining World Heritage Events Programme

Celebrating ten years of global recognition for Cornwall & west Devon’s mining heritage Events programme Eighty performances in over fifty venues across the ten World Heritage Site areas www.cornishmining.org.uk n July 2006, the Cornwall and west Devon Mining Landscape was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. To celebrate the 10th Ianniversary of this remarkable achievement in 2016, the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site Partnership has commissioned an exciting summer-long set of inspirational events and experiences for a Tinth Anniversary programme. Every one of the ten areas of the UK’s largest World Heritage Site will host a wide variety of events that focus on Cornwall and west Devon’s world changing industrial innovations. Something for everyone to enjoy! Information on the major events touring the World Heritage Site areas can be found in this leaflet, but for other local events and the latest news see our website www.cornish-mining.org.uk/news/tinth- anniversary-events-update Man Engine Double-Decker World Record Pasty Levantosaur Three Cornishmen Volvo CE Something BIG will be steaming through Kernow this summer... Living proof that Cornwall is still home to world class engineering! Over 10m high, the largest mechanical puppet ever made in the UK will steam the length of the Cornish Mining Landscape over the course of two weeks with celebratory events at each point on his pilgrimage. No-one but his creators knows what he looks like - come and meet him for yourself and be a part of his ‘transformation’: THE BIG REVEAL! -

Health and Adult Social Care Overview and Scrutiny Committee

Health and Adult Social Care Overview and Scrutiny Committee Rob Rotchell (Chairman) 2 Green Meadows Camelford Cornwall PL32 9UD 07828 980157 [email protected] Mike Eathorne-Gibbons (Vice-Chairman) 27 Lemon Street Truro Cornwall TR1 2LS 01872 275007 07979 864555 [email protected] Candy Atherton Top Deck Berkeley Path Falmouth Cornwall TR11 2XA 07587 890588 [email protected] John Bastin Eglos Cot Churchtown Budock Falmouth 01326 368455 [email protected] Nicky Chopak The Post House Tresmeer Launceston PL15 8QU 07810 302061 [email protected] Dominic Fairman South Penquite Farm Blisland Bodmin PL30 4LH 07939 122303 [email protected] Mario Fonk 25 Penarwyn Crescent, Heamoor, Penzance, TR18 3JU 01736 332720 [email protected] Loveday Jenkin Tremayne Farm Cottage Tremayne Praze an Beeble Camborne TR14 9PH 01209 831517 [email protected] Phil Martin Roseladden Mill Farm Sithney Helston Cornwall TR13 0RL 01326 569923 07533 827268 [email protected] Andrew Mitchell 36 Parc-An-Creet St Ives Cornwall TR26 2ES 01736 797538 07592 608390 [email protected] Karen McHugh C/O County Hall Treyew Road Truro Cornwall TR1 3AY 07977564422 [email protected] Sue Nicholas Brigstock, 8 Bampfylde Way Perran Downs, Goldsithney Penzance Cornwall TR20 9JJ 01736 711090 [email protected] David Parsons 56 Valley Road Bude Cornwall EX23 8ES 01288 354939 [email protected] John Thomas Gwel-An-Eglos, Church Row Lanner Redruth Cornwall TR16 6ET 01209 215162 07503 547852 [email protected] -

Cornwall Outdoors Brochure

Information Classification: CONTROLLED Contents Contacts pg 1 Introduction Head of Service, Safety on Educational Visits pg 2 The benefits of residential experience Andy Barclay, pg 3 Low season residentials T: 07968 892855 E: [email protected] pg 4 Activity days Bookings and Finance Mandy Richards pg 5 Mobile climbing wall T: 01872 326360 Bushcraft and survival skills E: [email protected] Pg 6 River Journeys Outdoor Education Courses Ann Kemp pg 7 - 8 Specialist activities T: 01872 326368 E: [email protected] pg 9 - 13 Professional development for outdoor leaders First aid courses Mountain Bike Instructor Award Scheme _ _ Coastal and countryside walking courses Safety on Educational Visits Summer moorland walking courses Paul Parkinson Winter moorland walking courses T: 07973241824 Powerboat courses E: [email protected] Learn to sail Climbing wall courses Delaware OEC Learning outside the classroom Dougie Bruce, Delaware OEC Paddlesport courses Drakewalls Gunnislake, PL18 9EH Bouldering and traversing walls in your T: 01822 833 885 E: [email protected] school grounds Teaching orienteering Parts 1 & 2 Porthpean OEC pg 14 National water safety management prog. Mark Peters, Porthpean OEC, Castle Gotha, pg 15 Outdoor learning leader award Porthpean, St Austell PL26 6AZ T: 01726 72901 pg 16 Booking information E: [email protected] pg 17 Organising a residential Carnyorth OEC Booking online Centre Contact, Carnyorth OEC, Carnyorth, St Just pg 18 - 19 Delaware OEC Penzance TR19 7QE pg 19 - 22 Porthpean OEC T: 01736 786 344 pg 23 Hire and supplies E: [email protected] Training room Hire pg 24 - 25 Carnyorth OEC pg 26 - 27 Pelistry Camp, Isles of Scilly pg 28 Educational visits pg 29 - 30 Booking terms and conditions pg 31 - 32 Application form www.cornwalloutdoors.org 1 Introduction Cornwall Outdoors is managed by Cornwall Council. -

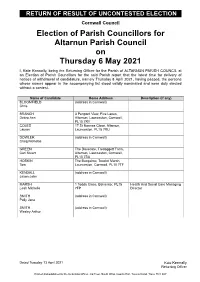

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Penzance | Newlyn | St Buryan | Porthcurno | Land’S End Open Top A1 Daily

Penzance | Newlyn | St Buryan | Porthcurno | Land’s End open top A1 daily route number A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 A1 Mondays to Fridays only not Sundays Penzance bus & rail station stand B 0630x 0835 0935 1035 1135 1235 1335 1435 1535 1635 1740 1740 Penzance Green Market 0633 0838 0938 1038 1138 1238 1338 1438 1538 1638 1743 1743 Saturdays only Penzance Alexandra Inn 0842 0942 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1542 1642 1747 1747 Newlyn Bridge 0846 0946 1046 1146 1246 1346 1446 1546 1646 1751 1751 this bus returns via St Buryan and Newlyn Gwavas Crossroads Chywoone Hill 0849 0949 1049 1149 1249 1349 1449 1549 1649 1754 1756 to Penzance Sheffield 0852 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1552 1652 1757 1801 this bus runs direct from Lamorna turn x 0857 0957 1057 1157 1257 1357 1457 1557 1657 1802 1807 Penzance to St Buryan via Drift Crossroads St Buryan Post Office 0648 0904 1004 1104 1204 1304 1404 1504 1604 1704 1809 1814 Treen bus shelter 0655 0911 1011 1111 1211 1311 1411 1511 1611 1711 1816 1821 Porthcurno car park 0701 0920 1020 1120 1220 1320 1420 1520 1620 1720 1825 1827 Land's End arr 0716 0937 1037 1137 1237 1337 1437 1537 1637 1737 1842 1844 same bus - no need to change A1 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 A3 Land's End dep 0719 0947 1047 1147 1247 1347 1447 1547 1647 1747 1847 1849 Sennen First and Last 0724 0952 1052 1152 1252 1352 1452 1552 1652 1752 1852 1854 extra journey on school days Sennen Cove 0730 0958 1058 1158 1258 1358 1458 1558 1658 1758 1858 1900 Penzance bus & rail station 1508 St Just bus station 1014 1114 1214 1314 1414 -

CARBINIDAE of CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander

CARBINIDAE OF CORNWALL Keith NA Alexander PB 1 Family CARABIDAE Ground Beetles The RDB species are: The county list presently stands at 238 species which appear to have been reliably recorded, but this includes • Grasslands on free-draining soils, presumably maintained either by exposure or grazing: 6 which appear to be extinct in the county, at least three casual vagrants/immigrants, two introductions, Harpalus honestus – see extinct species above two synathropic (and presumed long-term introductions) and one recent colonist. That makes 229 resident • Open stony, sparsely-vegetated areas on free-draining soils presumably maintained either by exposure breeding species, of which about 63% (147) are RDB (8), Nationally Scarce (46) or rare in the county (93). or grazing: Ophonus puncticollis – see extinct species above Where a species has been accorded “Nationally Scarce” or “British Red Data Book” status this is shown • On dry sandy soils, usually on coast, presumably maintained by exposure or grazing: immediately following the scientific name. Ophonus sabulicola (Looe, VCH) The various categories are essentially as follows: • Open heath vegetation, generally maintained by grazing: Poecilus kugelanni – see BAP species above RDB - species which are only known in Britain from fewer than 16 of the 10km squares of the National Grid. • Unimproved flushed grass pastures with Devil’s-bit-scabious: • Category 1 Endangered - taxa in danger of extinction Lebia cruxminor (‘Bodmin Moor’, 1972 & Treneglos, 1844) • Category 2 Vulnerable - taxa believed -

Goldmine Or Bottomless Pitt? Exploiting Cornwall's Mining Heritage

www.ssoar.info Goldmine or bottomless pitt? Exploiting Cornwall’s mining heritage Zwegers, Bart Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Zwegers, B. (2018). Goldmine or bottomless pitt? Exploiting Cornwall’s mining heritage. Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, 4(1), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1247534 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Diese Version ist zitierbar unter / This version is citable under: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-67086-7 Journal of Tourism, Heritage & Services Marketing, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 15-22, 2018 15 Goldmine or bottomless pitt? Exploiting Cornwall’s mining heritage Bart Zwegers Maastricht University, Netherlands Abstract: This research paper discusses the rise of the heritage and tourist industry in Cornwall. It aims to historically contextualize this process by analyzing it in relation to the neo-liberal political landscape of the 1980s. The paper highlights several consequences of industrial heritage tourism in the region, including the growing gap between rich and poor that resulted from the arrival of newcomers from the richer Eastern counties and the perceived downplaying of Cornish heritage. It will explain how these developments paved the way for regionalist activists who strived for more Cornish autonomy in the field of heritage preservation and exploitation. -

Wild Cornwall 135 Spring 2018-FINAL.Indd

Wild CornwallISSUE 135 SPRING 2018 Boiling seas Fish in a frenzy A future for wildlife in Cornwall Our new CE looks ahead Wildlife Celebration FREE ENTRY to Caerhays gardens Clues in the grass Woven nests reveal Including pull-out a tiny rodent diary of events Contacts Kestavow Managers Conservation contacts General wildlife queries Other local wildlife groups Chief Executive Conservation Manager Wildlife Information Service and specialist group contacts Carolyn Cadman Tom Shelley ext 272 (01872) 273939 option 3 For grounded or injured bats in Head of Nature Reserves Marine Conservation Officer Investigation of dead specimens Cornwall - Sue & Chris Harlow Callum Deveney ext 232 Abby Crosby ext 230 (excluding badgers & marine (01872) 278695 mammals) Wildlife Veterinary Bat Conservation Trust Head of Conservation Marine Awareness Officer Investigation Centre Matt Slater ext 251 helpline 0345 130 0228 Cheryl Marriott ext 234 Vic Simpson (01872) 560623 Community Engagement Officer, Botanical Cornwall Group Head of Finance & Administration Reporting dead stranded marine Ian Bennallick Trevor Dee ext 267 Your Shore Beach Rangers Project Natalie Gibb animals & organisms [email protected] Head of Marketing & Fundraising natalie.gibb@ Marine Strandings Network Hotline 0345 2012626 Cornish Hedge Group Marie Preece ext 249 cornwallwildlifetrust.org.uk c/o HQ (01872) 273939 ext 407 Reporting live stranded marine Manager Cornwall Youth Engagement Officer, Cornwall Bird Watching & Environmental Consultants Your Shore Beach Ranger Project -

AUGUST 2018 Price 50P

FIVE ALIVE The Magazine of the Redruth Team Ministry St Euny Redruth, Christchurch Lanner, St Andrew Pencoys St Andrew Redruth and St Stephen Treleigh AUGUST 2018 Price 50p Team Clergy Church Wardens Caspar Bush—Team Rector 01209 216958 St. Andrew Redruth Lez Seth 01209 215191 Peter Fellows 07903 807946 Sue Pearce 01209 217596 Jo Mulliner 01209 699979 St. Euny Redruth Graham Adamson 01209 315965 Margaret Johnson 01209 211352 Lay Readers Lucie Rogers 01209 211255 Jim Seth 01209 215191 Web site: www.miningchurch.uk Judith Williams 01209 202477 St. Andrew Pencoys Margaret Du Plessy 01209 481829 Jill Tolputt 01209 214638 Christchurch Lanner Magazine Editor/Treasurer Ross Marshall 01209 215695 Richard & Rosemary Robinson 01209 715198 Mary Anson 01209 211087 [email protected] St. Stephen’s Treleigh PASTORAL TEAM 07724 639854 Anne Youlton 01209 214532 ST EUNY OUTREACH WORKER 07971 574199 Christine Cunningham 01209 218147 (Clare Brown) Enquiries Concerning Church Halls St Andrew’s Crypt Lez Seth 01209 215191 Pencoys Church Hall Christine Walker 01209 215850 Lanner Church Hall Margaret Davis 01209 214470 Treleigh Church Hall David Rowe 01209 218416 Enquiries Concerning Weddings and Baptisms Please email Revd Caspar Bush on [email protected] or telephone 01209 216958 Benefice Office & weekly news sheet Administrator: Donna Bishop Tel office 01209 200739 (Please leave a message) E-mail: [email protected] Benefice website http://www.redruthchurch.org.uk Administrator: Alice Bush Email: [email protected] FIVE ALIVE MAGAZINE Subscriptions £6.00( PER YEAR OR 50P PER COPY): please contact your Churchwardens Articles and advertisements: please contact:- Richard and Rosemary Robinson: [email protected] by FRIDAY 17 AUGUST Rector’s notes – AUGUST 2018 How are we doing? I write this a couple of days after England went out of the World Cup at the semi-final stage.