RETALLACK SURNAME March 9 2000 by Greg Retallack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 20 July 2017 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 20 July 2017 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 20 July 2017). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Social Tariffs: Torfaen 19 ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Taxation: Electronic Hate Crime: Prosecutions 10 Government 19 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Technology and Innovation INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 10 Centres 20 Business: Broadband 10 UK Consumer Product Recall Review 20 Construction: Employment 11 Voluntary Work: Leave 21 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy: CABINET OFFICE 21 Mass Media 11 Brexit 21 Department for Business, Elections: Subversion 21 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Electoral Register 22 Staff 11 Government Departments: Directors: Equality 12 Procurement 22 Domestic Appliances: Safety 13 Intimidation of Parliamentary Economic Growth: Candidates Review 22 Environment Protection 13 Living Wage: Jarrow 23 Electrical Safety: Testing 14 New Businesses: Newham 23 Fracking 14 Personal Income 23 Insolvency 14 Public Sector: Blaenau Gwent 24 Iron and Steel: Procurement 17 Public Sector: Cardiff Central 24 Mergers and Monopolies: Data Public Sector: Ogmore 24 Protection 17 Public Sector: Swansea East 24 Nuclear Power: Treaties 18 Public Sector: Torfaen 25 Offshore Industry: North Sea 18 Public Sector: Wrexham 25 Performing Arts 18 Young People: Cardiff Central -

Fish) of the Helford Estuary

HELFORD RIVER SURVEY A survey of the Pisces (Fish) of the Helford Estuary A Report to the Helford Voluntary Marine Conservation Area Group funded by the World Wide Fund for Nature U.K. and English Nature P A Gainey 1999 1 Summary The Helford Voluntary Marine Conservation Area (hereafter HVMCA) was designated in 1987 and since that time a series of surveys have been carried out to examine the flora and fauna present. In this study no less that eighty species of fish have been identified within the confines of the HVMCA. Many of the more common fish were found to be present in large numbers. Several species have been designated as nationally scarce whilst others are nationally rare and receive protection at varying levels. The estuary is obviously an important nursery for several species which are of economic importance. A full list of the fish species present and the protection some of them receive is given in the Appendices Nine species of fish have been recorded as new to the HVMCA. ISBN 1 901894 30 4 HVMCA Group Office Awelon, Colborne Avenue Illogan, Redruth Cornwall TR16 4EB 2 CONTENTS Summary Location Map - Fig. 1.......................................................................................................... 1 Intertidal sites - Fig. 2 ......................................................................................................... 2 Sublittoral sites - Fig. 3 ...................................................................................................... 3 Bathymetric chart - Fig. 4 ................................................................................................. -

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

INTRODUCTION I the CALENDAR the Plymouth Ordo Is Based on The

INTRODUCTION I THE CALENDAR The Plymouth Ordo is based on the General Calendar of the Church, the approved National Calendar for England, and the approved Calendar proper for the Diocese of Plymouth. II MOVABLE FEASTS and Weekday Holydays of Obligation First Sunday of Advent 2nd December 2018 The Nativity of the Lord 25th December (Tuesday) The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph 30th December (Sunday) Mary, Mother of God 1st January 2019 (Tuesday) The Epiphany 6th January (Sunday) The Baptism of the Lord 13th January (Sunday) Ash Wednesday 6th March Easter Sunday 21st April St George – transferred 30th April (Tuesday) The Ascension of the Lord 30th May (Thursday) Pentecost Sunday 9th June The Most Holy Trinity 16th June The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ 23rd June (Sunday) The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus 28th June (Friday) The Immaculate Heart of Mary 29th June (Saturday) St Peter & St Paul 30th June (Sunday) Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe 24th November First Sunday of Advent 1st December The Immaculate Conception - transferred 9th December (Monday) The Nativity of the Lord 25th December (Wednesday) The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph 29th December (Sunday) III THE MASS MASS FOR THE PEOPLE is to be said on Sundays and Solemnities which are Holydays of Obligation. Canon 534: After a pastor has taken possession of his parish, he is obliged to apply the Mass for the people entrusted to him on each Sunday and Holy Day of Obligation in his diocese. If he is legitimately impeded from this celebration however, he is to apply it on the same days through another or on other days himself. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = the National Library of Wales Cymorth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, (GB 0210 WINCOOANT) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/winifred-coombe-tennant-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Winifred Coombe Tennant Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans

Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plans 1 2 Contents Page 2 Chairman’s Introduction Page 3 Arthuret Community Plan Introduction Page 4 Kirkandrews-on-Esk Plan Introduction Page 5 Arthuret Parish background and History Page 7 Brief outline of Kirkandrews on Esk Parish and History Page 9 Arthuret Parish Process Page 12 Kirkandrews on Esk Parish Process Page 18 The Action Plan 3 Chairman’s Introduction Welcome to the Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan – a joint Community Action Plan for the parishes of Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk. The aim is to encourage local people to become involved in ensuring that what matters to them – their ideas and priorities – are identified and can be acted upon. The Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan is based upon finding out what you value in your community. Then, based upon the process of consultation, debate and dialogue, producing an Action Plan to achieve the aspirations of local people for the community you live and work in. The consultation process took several forms including open days, questionnaires, workshops, focus group meetings, even a business speed dating event. The process was interesting, lively and passionate, but extremely important and valuable in determining the vision that you have for your community. The information gathered was then collated and produced in the following Arthuret and Kirkandrews on Esk Community Plan. The Action Plan aims to show a balanced view point by addressing the issues that you want to be resolved and celebrating the successes we have achieved. It contains a range of priorities from those which are aspirational to those that can be delivered with a few practical steps which will improve life in our community. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local

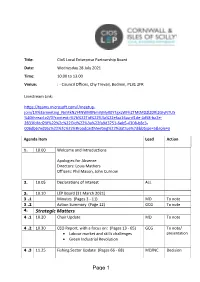

Title: CIoS Local Enterprise Partnership Board Date: Wednesday 28 July 2021 Time: 10.00 to 13.00 Venue: : - Council Offices, Chy Trevail, Bodmin, PL31 2FR Livestream Link: https://teams.microsoft.com/l/meetup- join/19%3ameeting_NmFkNzY4NWMtNmVjMy00YTgxLWFhZTMtMDZlZDRlZGIyNTU5 %40thread.v2/0?context=%7b%22Tid%22%3a%22efaa16aa-d1de-4d58-ba2e- 2833fdfdd29f%22%2c%22Oid%22%3a%22fa9d3751-6eb5-4308-b8c3- 006db67ed9ac%22%2c%22IsBroadcastMeeting%22%3atrue%7d&btype=a&role=a Agenda Item Lead Action 1. 10.00 Welcome and Introductions Apologies for Absence Directors: Louis Mathers Officers: Phil Mason, John Curnow 2. 10.05 Declarations of Interest ALL 3. 10.10 LEP Board (31 March 2021) 3 .1 Minutes (Pages 3 - 11) MD To note 3 .2 Action Summary (Page 12) GCG To note 4. Strategic Matters 4 .1 10.20 Chair Update MD To note 4 .2 10.30 CEO Report, with a focus on: (Pages 13 - 65) GCG To note/ Labour market and skills challenges presentation Green Industrial Revolution 4 .3 11.25 Fishing Sector Update (Pages 66 - 68) MD/NC Decision Page 1 4 .4 11.50 Nominations Committee Update (Pages 69 - GCG Decision 122) 4 .5 12.15 Audit & Assurance Committee Update (Pages GCG Decision 123 - 198) 4 .6 12.25 Enterprise Zones Board Update (Pages 199 - SJ/GCG To note 202) 4 .7 12.35 Any other business 5. Exclusion of Press and Public 5 .1 12.40 Investment & Oversight Panel Update (Pages MD/GCG To note 203 - 206) 5 .2 12.50 Any other confidential business ALL Page 2 Agenda No. 3.1 Information Classification: CONTROLLED CORNWALL AND ISLES OF SCILLY LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP MINUTES of a Meeting of the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Local Enterprise Partnership held in the Online - Virtual Meeting on Wednesday 31 March 2021 commencing at 10.00 am. -

Kirkandrews on Esk: Introduction1

Victoria County History of Cumbria Project: Work in Progress Interim Draft [Note: This is an incomplete, interim draft and should not be cited without first consulting the VCH Cumbria project: for contact details, see http://www.cumbriacountyhistory.org.uk/] Parish/township: KIRKANDREWS ON ESK Author: Fay V. Winkworth Date of draft: January 2013 KIRKANDREWS ON ESK: INTRODUCTION1 1. Description and location Kirkandrews on Esk is a large rural, sparsely populated parish in the north west of Cumbria bordering on Scotland. It extends nearly 10 miles in a north-east direction from the Solway Firth, with an average breadth of 3 miles. It comprised 10,891 acres (4,407 ha) in 1864 2 and 11,124 acres (4,502 ha) in 1938. 3 Originally part of the barony of Liddel, its history is closely linked with the neighbouring parish of Arthuret. The nearest town is Longtown (just across the River Esk in Arthuret parish). Kirkandrews on Esk, named after the church of St. Andrews 4, lies about 11 miles north of Carlisle. This parish is separated from Scotland by the rivers Sark and Liddel as well as the Scotsdike, a mound of earth erected in 1552 to divide the English Debatable lands from the Scottish. It is bounded on the south and east by Arthuret and Rockcliffe parishes and on the north east by Nicholforest, formerly a chapelry within Kirkandrews which became a separate ecclesiastical parish in 1744. The border with Arthuret is marked by the River Esk and the Carwinley burn. 1 The author thanks the following for their assistance during the preparation of this article: Ian Winkworth, Richard Brockington, William Bundred, Chairman of Kirkandrews Parish Council, Gillian Massiah, publicity officer Kirkandrews on Esk church, Ivor Gray and local residents of Kirkandrews on Esk, David Grisenthwaite for his detailed information on buses in this parish; David Bowcock, Tom Robson and the staff of Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle; Stephen White at Carlisle Central Library. -

The Cornish Mining World Heritage Events Programme

Celebrating ten years of global recognition for Cornwall & west Devon’s mining heritage Events programme Eighty performances in over fifty venues across the ten World Heritage Site areas www.cornishmining.org.uk n July 2006, the Cornwall and west Devon Mining Landscape was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. To celebrate the 10th Ianniversary of this remarkable achievement in 2016, the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site Partnership has commissioned an exciting summer-long set of inspirational events and experiences for a Tinth Anniversary programme. Every one of the ten areas of the UK’s largest World Heritage Site will host a wide variety of events that focus on Cornwall and west Devon’s world changing industrial innovations. Something for everyone to enjoy! Information on the major events touring the World Heritage Site areas can be found in this leaflet, but for other local events and the latest news see our website www.cornish-mining.org.uk/news/tinth- anniversary-events-update Man Engine Double-Decker World Record Pasty Levantosaur Three Cornishmen Volvo CE Something BIG will be steaming through Kernow this summer... Living proof that Cornwall is still home to world class engineering! Over 10m high, the largest mechanical puppet ever made in the UK will steam the length of the Cornish Mining Landscape over the course of two weeks with celebratory events at each point on his pilgrimage. No-one but his creators knows what he looks like - come and meet him for yourself and be a part of his ‘transformation’: THE BIG REVEAL! -

Cornish Archaeology 41–42 Hendhyscans Kernow 2002–3

© 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society CORNISH ARCHAEOLOGY 41–42 HENDHYSCANS KERNOW 2002–3 EDITORS GRAEME KIRKHAM AND PETER HERRING (Published 2006) CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © COPYRIGHT CORNWALL ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2006 No part of this volume may be reproduced without permission of the Society and the relevant author ISSN 0070 024X Typesetting, printing and binding by Arrowsmith, Bristol © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Contents Preface i HENRIETTA QUINNELL Reflections iii CHARLES THOMAS An Iron Age sword and mirror cist burial from Bryher, Isles of Scilly 1 CHARLES JOHNS Excavation of an Early Christian cemetery at Althea Library, Padstow 80 PRU MANNING and PETER STEAD Journeys to the Rock: archaeological investigations at Tregarrick Farm, Roche 107 DICK COLE and ANDY M JONES Chariots of fire: symbols and motifs on recent Iron Age metalwork finds in Cornwall 144 ANNA TYACKE Cornwall Archaeological Society – Devon Archaeological Society joint symposium 2003: 149 archaeology and the media PETER GATHERCOLE, JANE STANLEY and NICHOLAS THOMAS A medieval cross from Lidwell, Stoke Climsland 161 SAM TURNER Recent work by the Historic Environment Service, Cornwall County Council 165 Recent work in Cornwall by Exeter Archaeology 194 Obituary: R D Penhallurick 198 CHARLES THOMAS © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society © 2006, Cornwall Archaeological Society Preface This double-volume of Cornish Archaeology marks the start of its fifth decade of publication. Your Editors and General Committee considered this milestone an appropriate point to review its presentation and initiate some changes to the style which has served us so well for the last four decades. The genesis of this style, with its hallmark yellow card cover, is described on a following page by our founding Editor, Professor Charles Thomas. -

Wave Hub Appendix N to the Environmental Statement

South West of England Regional Development Agency Wave Hub Appendix N to the Environmental Statement June 2006 Report No: 2006R001 South West Wave Hub Hayle, Cornwall Archaeological assessment Historic Environment Service (Projects) Cornwall County Council A Report for Halcrow South West Wave Hub, Hayle, Cornwall Archaeological assessment Kevin Camidge Dip Arch, MIFA Charles Johns BA, MIFA Philip Rees, FGS, C.Geol Bryn Perry Tapper, BA April 2006 Report No: 2006R001 Historic Environment Service, Environment and Heritage, Cornwall County Council Kennall Building, Old County Hall, Station Road, Truro, Cornwall, TR1 3AY tel (01872) 323603 fax (01872) 323811 E-mail [email protected] www.cornwall.gov.uk 3 Acknowledgements This study was commissioned by Halcrow and carried out by the projects team of the Historic Environment Service (formerly Cornwall Archaeological Unit), Environment and Heritage, Cornwall County Council in partnership with marine consultants Kevin Camidge and Phillip Rees. Help with the historical research was provided by the Cornish Studies Library, Redruth, Jonathan Holmes and Jeremy Rice of Penlee House Museum, Penzance; Angela Broome of the Royal Institution of Cornwall, Truro and Guy Hannaford of the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, Taunton. The drawing of the medieval carved slate from Crane Godrevy (Fig 43) is reproduced courtesy of Charles Thomas. Within the Historic Environment Service, the Project Manager was Charles Johns, who also undertook the terrestrial assessment and walkover survey. Bryn Perry Tapper undertook the GIS mapping, computer generated models and illustrations. Marine consultants for the project were Kevin Camidge, who interpreted and reported on the marine geophysical survey results and Phillip Rees who provided valuable advice. -

Cornish Association of NSW - No

Lyther Nowodhow - Newsletter - of the Cornish Association of NSW - No. 377 - November / December, 2018 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Committee News:. 'Renumber Clause 16 as 176 Bank account at 31/10/18 bal: $9,046.37 If you wish to have another copy of the Rules “It was great to have 23 members and friends prior to the meeting, the document is available at our lunch on 21 November! I wish all our to print or download from our web site at: members, and their families, a very Australian & Cornish Christmas and now look forward to h p:11members.optusnet.com.au10evrenor1 seeing you at our AGM and St Piran’s lunch on canswrul.pdf 2 March. Please keep the date free!“ Joy Dunkerley, President You and your ideas are always welcome Our Lending & Research Library Committee Meeting held 5 November: Most Our librarian, Eddie Lyon, has stepped down nd of us met, for the 2 time in 2018 and from the role due to a pending tree-change discussion covered: minutes and move. The material has been relocated, and we correspondence, reports from the office bearers will bring you more information later. (incl. a provisional financial report for the year), discussion on the future program, including the AGM and St Piran’s Lunch and on a proposal from the Secretary for Rule changes. NOTICE OF AGM The full listing of books has been on the CANSW web site for some time. The direct page link to Members are hereby informed that our Annual view is: General Meeting will be held on Saturday 2 http://members.optusnet.com.au/~kevrenor/ March, 2019, at Ryde Eastwood Leagues Club, canswlib5_alpha.xls Ryedale Road West Ryde.