Important Bird Areas Americas - Priority Sites for Biodiversity Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Argentina New Birding ‘Lodges’ in Argentina James Lowen

>> BIRDING SITES NEW BIRDING LoDGES IN ARGENTINA New birding ‘lodges’ in Argentina James Lowen Birders visiting Argentina tend to stay in hotels near but not at birding sites because the country lacks lodges of the type found elsewhere in the Neotropics. However, a few new establishments are bucking the trend and may deserve to be added to country’s traditional birding route. This article focuses on two of them and highlights a further six. Note: all photographs were taken at the sites featured in the article. Long-trained Nightjar Macropsalis forcipata, Posada Puerto Bemberg, Misiones, June 2009 (emilio White); there is a good stakeout near the posada neotropical birding 6 49 >> BIRDING SITES NEW BIRDING LoDGES IN ARGENTINA lthough a relatively frequent destination Posada Puerto Bemberg, for Neotropical birders, Argentina—unlike A most Neotropical countries—has relatively Misiones few sites such as lodges where visitors can Pretty much every tourist visiting Misiones bird and sleep in the same place. Fortunately, province in extreme north-east Argentina makes there are signs that this is changing, as estancia a beeline for Iguazú Falls, a leading candidate to owners build lodgings and offer ecotourism- become one of UNESCO’s ‘seven natural wonders related services. In this article, I give an of the world’. Birders are no different, but also overview of two such sites that are not currently spend time in the surrounding Atlantic Forest on the standard Argentine birding trail—but of the Parque Nacional de Iguazú. Although should be. Both offer good birding and stylish some birders stay in the national park’s sole accommodation in a beautiful setting, which may hotel, most day-trip the area from hotels in interest those with non-birding partners. -

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation

THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PRODUCED IN GUIANAS COLLABORATION VERZICHT APERWITH: Ç 2016 Biodiversity of the Southern Rupununi Savannah World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 WWF-Guianas Global Wildlife Conservation Guyana Office PO Box 129 285 Irving Street, Queenstown Austin, TX 78767 USA Georgetown, Guyana [email protected] www.wwfguianas.org [email protected] Text: Juliana Persaud, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Concept: Francesca Masoero, WWF-Guianas, Guyana Office Design: Sita Sugrim for Kriti Review: Brian O’Shea, Deirdre Jaferally and Indranee Roopsind Map: Oronde Drakes Front cover photos (left to right): Rupununi Savannah © Zach Montes, Giant Ant Eater © Gerard Perreira, Red Siskin © Meshach Pierre, Jaguar © Evi Paemelaere. Inside cover photo: Gallery Forest © Andrew Snyder. OF BIODIVERSITYTHE SOUTHERN RUPUNUNI SAVANNAH. Guyana-South America. World Wildlife Fund and Global Wildlife Conservation 2016 This booklet has been produced and published thanks to: 1 WWF Biodiversity Assessment Team Expedition Southern Rupununi - Guyana. The Southern Rupununi Biodiversity Survey Team / © WWF - GWC. Biodiversity Assessment Team (BAT) Survey. This programme was created by WWF-Guianas in 2013 to contribute to sound land- use planning by filling biodiversity data gaps in critical areas in the Guianas. As far as possible, it also attempts to understand the local context of biodiversity use and the potential threats in order to recommend holistic conservation strategies. The programme brings together local knowledge experts and international scientists to assess priority areas. With each BAT Survey, species new to science or new country records are being discovered. This booklet acknowledges the findings of a BAT Survey carried out during October-November 2013 in the southern Rupununi savannah, at two locations: Kusad Mountain and Parabara. -

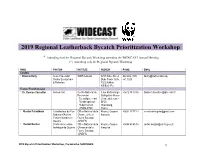

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop

2019 Regional Leatherback Bycatch Prioritization Workshop * Attending both the Regional Bycatch Workshop attending the WIDECAST Annual Meeting (*) Attending only the Regional Bycatch Workshop NAME POSITION INSTITUTE ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL Canada: * Brianne Kelly Senior Specialist WWF-Canada 5251 Duke Street 902.482.1105 [email protected] Marine Ecosystems Duke Tower Suite ext. 3025 & Fisheries 1202 Halifax NS B3J 1P3 France/ French-Guiane * Dr. Damien Chevallier Researcher Centre National de 3 rue Michel-Ange +0612 97 10 54 [email protected] Recherche Délégation Alsace Scientifique – Inst 23 rue du Loess – Pluridisciplinaire BP20 Hubert Curien Strasbourg, (CNRS-IPHC) France * Nicolas Paranthoën Coordinateur du Plan Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 13 77 44 [email protected] National d'Actions Chasse et de la française Tortues Marines en Faune Sauvage Guyane (ONCFS) * Rachel Berzins Cheffe de la cellule Office National de la Kourou, Guyane +0694 40 45 14 [email protected] technique de Guyane Chasse et de la française Faune Sauvage (ONCFS) 2019 Bycatch Prioritization Workshop, Paramaribo SURINAME 1 * Christelle Guyon Chargée de mission Direction de Rue Carlos +0594 29 68 60 Christelle.guyon@developpement- biodiversité marine l’Environnement, de Fineley CS 76003, durable.gouv.fr l’Aménagement et 97306 Cayenne du Logement Guyane française de Guyane * Nolwenn Cozannet Chargée du projet WWF France, 2, rue Gustave +0594 31 38 28 [email protected] Dauphin de Guyane bureau Guyane Charlery 97 300 CAYENNE -

Polystictus Pectoralis Polystictus Herrera Oytcu Pectoralis, Polystictus Elaeis Guineensis Elaeis

Nuevas localidades para el Tachurí barbado (Polystictus Breve Nota pectoralis) en la Orinoquía Colombiana New localities for the Bearded Tachuri (Polystictus pectoralis) in Colombian Orinoquía Juan M. Ruiz-Ovalle 1,2 & Sergio Chaparro-Herrera1 1Asociación Bogotana de Ornitología (ABO), Bogotá, Colombia 2The Nature Conservancy (TNC)-Colombia,, Bogotá, Colombia. [email protected], [email protected] Ornitología Colombiana Ornitología Resumen Entre julio de 2011 y marzo de 2012 registramos Polystictus pectoralis, una especie casi amenazada y poco conocida en Colombia, en el oriente del país región de los Llanos Orientales, municipio de Orocué, departamento de Casanare, asociada a cultivos de palma de aceite (Elaeis guineensis) con canales de riego y sabana arbustiva de Andropogon sp. Incluimos ade- más información de dos localidades nuevas adicionales (Trinidad, departamento de Casanare y Puerto Carreño, departa- mento de Vichada), además de información sobre el comportamiento y vocalizaciones y las posibles amenazas para esta especie en la región. Palabras clave: Andropogon, Colombia, distribución, Elaeis guineensis, Orinoquía, sabanas, Tyrannidae. Abstract Between July 2011 and March 2012, we recorded Polystictus pectoralis, a little-known species in Colombia considered Near Threatened, in the Llanos Orientales of eastern Colombia in the municipality of Orocué, department of Casanare, where it colombiana/ colombiana/ - occurred near irrigation canals amid oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) plantations and in brushy savanna of Andropogon sp. We also include two additional new localities (Trinidad, department of Casanare y Puerto Carreño, department of Vichada), as well as descriptions of behavior and vocalizations and potential threats to this species in the region. Key words: Andropogon, Colombia, distribution, Elaeis guineensis, Orinoquía, savannas, Tyrannidae. -

Additions to the Avifauna of Two Localities in the Southern Rupununi Region, Guyana 17

13 4 113–120 21 July 2017 NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 13 (4): 113–120 https://doi.org/10.15560/13.4.113 Additions to the avifauna of two localities in the southern Rupununi region, Guyana Brian J. O’Shea,1, 2 Asaph Wilson,3 Jonathan K. Wrights4 1 North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, 11 W. Jones Street, Raleigh, NC, 27601, USA, 2 Global Wildlife Conservation, PO Box 129, Austin TX 78767, USA. 3 South Rupununi Conservation Society, Shulinab, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo, Guyana. 4 National Agricultural Research and Extension Institute, National Plant Protection Organization, Mon Repos, East Coast Demerara, Guyana. Corresponding author: Brian J. O’Shea, [email protected] Abstract We report new records from ornithology surveys conducted at Kusad Mountain and Parabara savanna in Guyana’s southern Rupununi region during October and November 2013. Both localities had existing species lists based on surveys conducted in 2000, but had not been formally surveyed since. We surveyed birds over 15 field days, adding 22 and 10 species to the existing lists for Kusad and Parabara, respectively. Our findings augment prior knowledge of the status and distribution of birds in this region of the Guiana Shield. The southern Rupununi harbors high avian diversity, including rare species such as Rio Branco Antbird (Cercomacra carbonaria), Hoary-throated Spinetail (Synallaxis kollari), Bearded Tachuri (Polystictus pectoralis), and Red Siskin (Spinus cucullatus), which are likely to continue to draw tourism revenue to local communities if their habitats remain intact. Key words Neotropics; Guiana Shield; birds; inventory; conservation; savanna; ecotourism. Academic editor: Nárgila Gomes Moura | Received 9 December 2016 | Accepted 6 May 2017 | Published 21 July 2017 Citation: O’Shea BJ, Wilson A, Wrights JK (2017) Additions to the avifauna of two localities in the southern Rupununi region, Guyana. -

Pdf Projdoc.Pdf

Coming Through the Hard Times One Earth Conservation Annual Report 2020 Table of Contents Letter from the Co-Directors 3 Mission & Accomplishments 4 Going Virtual 6 Science 8 Conservation 2020 10 Organization 20 Financial Report 22 Thank You! 24 Letter from the Co-directors 2 Dear One Earthers, The past year, 2020, was a very hard one for so many who were overwhelmed by the pandemic, politics, protests, powerful precipitation, and precarious populations of parrots, among other things. One Earth Conservation’s parrot conservation projects have had more than their share of hard times. Just when it seems that we have come through one hard time, along comes another, and another. Paraphrasing Stephen Foster’s song “Hard Times Come Again No More,” there are frail forms fainting at the door, and though their voices are silent, their pleading looks rock us to the core. How can we keep hard times coming no more, for ourselves and others? The short answer is we cannot. Life is hardship and tragedy. And it is also joy and beauty. There is no beauty without tragedy, and no tragedy without beauty. Both are woven into existence, but we do believe it is possible to weave more color into the drab fabric that smothers so many lives. We do so by bringing hope, and, at the same time, this work allows one to live joyously while in a state of profound grief. This hope arises from our faith that we can accept reality just as it is in all its beauty and tragedy. We see the suffering of others, and how our lives interweave with the tragedy of the commons that causes hunger through ecosystem failure and loss of biodiversity and climate crisis-fueled hurricanes. -

Parrots in the London Area a London Bird Atlas Supplement

Parrots in the London Area A London Bird Atlas Supplement Richard Arnold, Ian Woodward, Neil Smith 2 3 Abstract species have been recorded (EASIN http://alien.jrc. Senegal Parrot and Blue-fronted Amazon remain between 2006 and 2015 (LBR). There are several ec.europa.eu/SpeciesMapper ). The populations of more or less readily available to buy from breeders, potential factors which may combine to explain the Parrots are widely introduced outside their native these birds are very often associated with towns while the smaller species can easily be bought in a lack of correlation. These may include (i) varying range, with non-native populations of several and cities (Lever, 2005; Butler, 2005). In Britain, pet shop. inclination or ability (identification skills) to report species occurring in Europe, including the UK. As there is just one parrot species, the Ring-necked (or Although deliberate release and further import of particular species by both communities; (ii) varying well as the well-established population of Ring- Rose-ringed) parakeet Psittacula krameri, which wild birds are both illegal, the captive populations lengths of time that different species survive after necked Parakeet (Psittacula krameri), five or six is listed by the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) remain a potential source for feral populations. escaping/being released; (iii) the ease of re-capture; other species have bred in Britain and one of these, as a self-sustaining introduced species (Category Escapes or releases of several species are clearly a (iv) the low likelihood that deliberate releases will the Monk Parakeet, (Myiopsitta monachus) can form C). The other five or six¹ species which have bred regular event. -

Special Update on Quito Process V Technical Meeting on Human

Special update on Quito Process AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN AS OF NOVEMBER 2019 LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN V Technical Meeting on HumanV EMobilityNEZUVELEANNEZUE LofAN Venezuelan Citizens in the RegionREFUGEERSE F&U MGIEGERSA &N TMSIG INR ATNHTES R IENG TIOHNE REGION UNITED STATES UNITED STATES BOGOTA, COLOMBIA Havana\ MEXICO Havana\ MEXICO CUBA DOMINICAN 14-15 NOVEMBER 2019 CUBA DOMINICAN \ REPUBLIC Mexico \ HAITI \ PUERTO REPUBLIC Mexico JAMAICA \ Santo HAITI \ PUERTO City \BELIZE JAMAICA \ RICO City \ Domingo Santo RICO BELIZE Domingo \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA GUATEMALA \ \ HONDURAS CARIBBEAN SEA \ GUATEMALA \ EL SALVADOR NICARAGUA \ ARUBA CURACAO \ EL SALVADOR APoRrUt BA \NICARAGUA Spain CURACAO Port San José \ \ TRINIDAD Spain \ Panamá San JoséCaracas & TOBA\GO \ TRINIDAD PARTICIPATION COSTA \ \ Caracas Panamá & TOBAGO COSTA \ RICA PANAMA Georgetown RICA PANAMAVENEZUELA \ Georgetown VENEZ\UPaErLaAmaribo \ GUYANA Paramaribo \Bogotá \ CGayUeYnAneNA \ \Bogotá \ Cayenne COLOMBIA SURINAME COLOMBIA FRENCH SURINAME GUYANA FRENCH The fifth round of the Quito Process (Quito V – GUYANA \Quito \Quito ECUADOR Bogota Chapter) took place on 14-15 November ECUADOR (2019), with the participation of 12 States from PERU Latin America and the Caribbean, along with PERU \Lima BRAZIL key cooperating States, international financial \Lima BRAZIL \ BOLIVIA Brasilia \ BOLIVIA Brasilia institutions and other actors. \ \ Sucre Sucre PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC PACIFIC PARAGUAY ATLANTIC OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN The meeting follows up on four previous meetings OCEAN Asunción \ OCEAN QUITO V DECLARATION in September and November 2018, April and July QUITO V DECLARATION SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA SIGNATORIES ARGENTINA 2019, as part of a government-led initiative thatArge ntina \ URUGUAY Argentina \ URUGUAY Santiago \ \ Santiago \ Brazil Buenos Montevideo \ aims to harmonize the policies and practices of Brazil Aires Buenos Montevideo Chile CHILE Aires Chile CHILE the countries in the region. -

CBD Fifth National Report

i ii GUYANA’S FIFTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Approved by the Cabinet of the Government of Guyana May 2015 Funded by the Global Environment Facility Environmental Protection Agency Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment Georgetown September 2014 i ii Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ........................................................................................................................................ V ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... I 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 DESCRIPTION OF GUYANA .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 RATIFICATION AND NATIONAL REPORTING TO THE UNCBD .............................................................................................. 2 1.3 BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF GUYANA’S BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY ................................................................................................. 3 SECTION I: STATUS, TRENDS, THREATS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR HUMAN WELL‐BEING ...................................... 12 2. IMPORTANCE OF BIODIVERSITY -

Wildlife in Surinam Joop P

Wildlife in Surinam Joop P. Schu/z, Russell A. Mittermeler, Henry A. Reich art Surinam is one of the few countries in the world where uninhabited and undisturbed tropical rain forest still covers large areas. The Government is fully aware of the importance of this natural heritage. Wildlife is protected, and eight nature reserves, ranging in size from 4000 to 22,000 ha, have been created to protect representative habitats - forest, savannas, coastal flats and important breeding beaches for Kemp's ridley, green and leatherback turtles. The Republic of Surinam, a former Dutch colony that became fully independent in November 1975, is one of the most thinly populated countries in South America. Only 375,000 people inhabit 162,000 sq. km, and almost 90 per cent are concentrated in the capital, Paramaribo, and smaller settlements on the coastal plain. In the interior live some 50,000 Bushnegroes and Amerindians, mostly in scattered villages along the Suriname, Marowijne and Saramacca Rivers. As the rest of the country is covered with uninhabited and undisturbed Neotropical rain forest, Surinam offers unequalled opportunities for preserving primeval tropical forest ecosystems. In the north and the extreme south there are a variety of unusual savanna types, and the coast has bird colonies and turtle nesting beaches of major importance. The Surinam government, realising the value of the country's natural heritage, has set aside eight reserves and one nature park as a first step in protecting a representative cross-section of the flora and fauna. Several of these reserves are readily accessible and offer superb opportunities for tourism and scientific research. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their