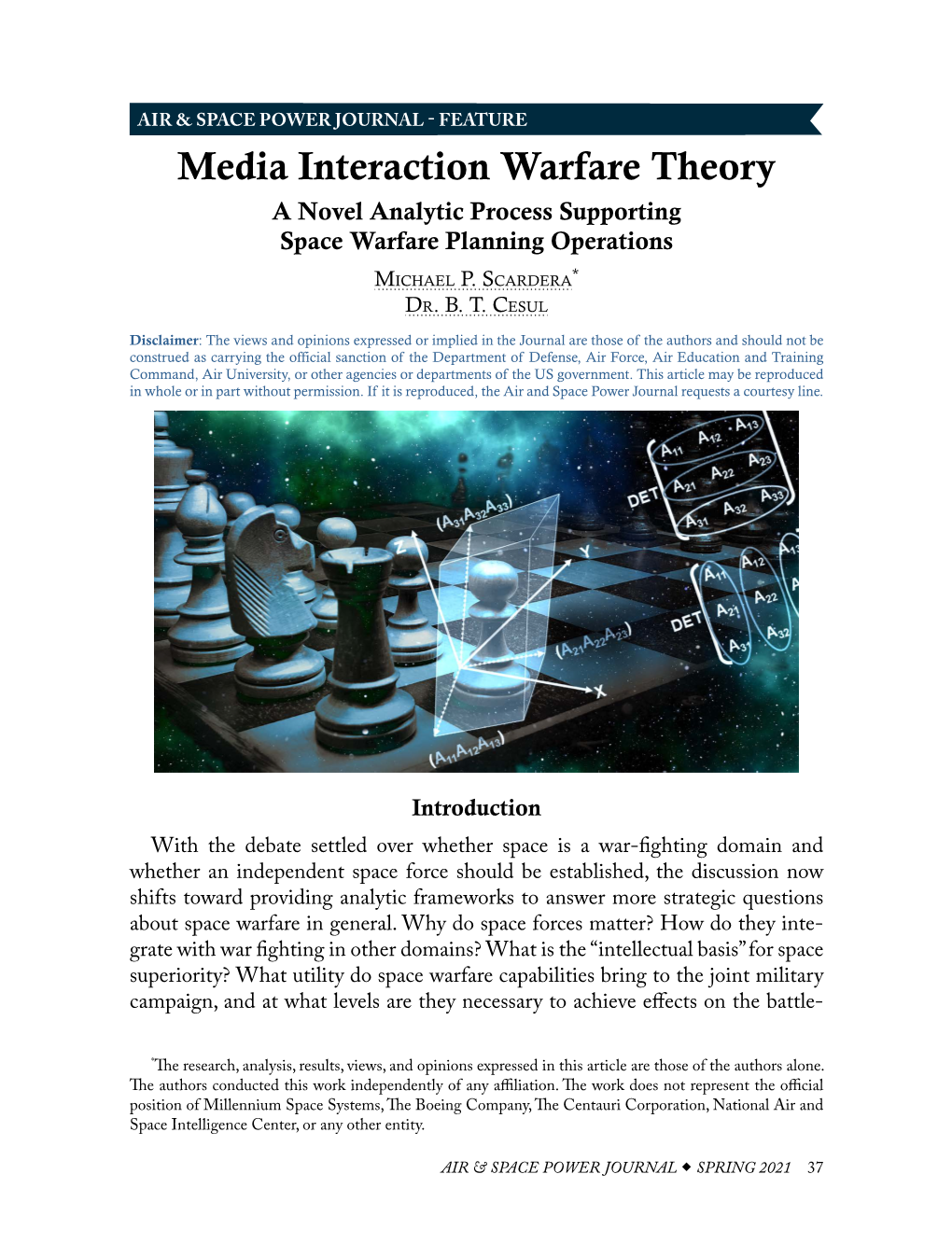

Media Interaction Warfare Theory a Novel Analytic Process Supporting Space Warfare Planning Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China's Far Sea's Navy: the Implications Of

China’s Far Sea’s Navy: The Implications of the “Open Seas Protection” Mission Revised and Updated April 2016 A Paper for the “China as a Maritime Power” Conference CNA Arlington, Virginia Michael McDevitt Senior Fellow Introduction China has not yet revealed the details of how large a navy it feels it needs, but Beijing has been remarkably transparent in disclosing its overall maritime ambitions, which depend first and foremost on a strong PLAN. Three years ago, the PLA explicitly addressed the issue of becoming a “maritime power”: China is a major maritime as well as land country. The seas and oceans provide immense space and abundant resources for China’s sustainable development, and thus are of vital importance to the people's well-being and China’s future. It is an essential national development strategy to exploit, utilize and protect the seas and oceans, and build China into a maritime power. It is an important duty for the PLA to resolutely safeguard China's maritime rights and interests. (Emphasis added.)1 Two years later, the PLA was even more specific in addressing its far seas ambitions. These ambitions were dictated by Beijing’s belief that it must be able to protect its vital sea lanes and its many political and economic overseas interests—including, of course, the millions of Chinese citizens working or travelling abroad. This was explicitly spelled out in the 2015 Chinese Defense White Paper, entitled China’s Military Strategy.2 According to the white paper:3 1 See State Council Information Office, The Diversified Employment of China’s Armed Forces, April 2013, Beijing. -

Amphibious Warfare: Theory and Practice* Tomoyuki Ishizu

Amphibious Warfare: Theory and Practice* Tomoyuki Ishizu Introduction In December 2013, the Government of Japan released its first “National Security Strategy” and announced the “National Defense Program Guidelines for FY 2014 and beyond.” The new Guidelines set forth the buildup of “dynamic joint defense force,” calling for a sufficient amphibious operations capability by means of amphibious vehicles and tilt-rotor aircraft, for example, to cope with potential enemy attack against any of Japan’s remote islands. This paper analyzes amphibious warfare from a historical viewpoint to show its major framework and concept. It is no wonder that the scale and form of amphibious operations may differ significantly among states depending on their national strategy, status of military power in the national strategy, military objectives, and historical or geographical conditions. The reason is that the national strategy, which is prescribed according to the national history, geography, culture and more, determines the role of the nation’s military force and way of fighting. With all these facts taken into account, this paper attempts to propose a general framework for examining amphibious warfare, especially for amphibious operations, and to sort out ideas and terms used in such operations. 1. What are Amphibious Operations? (1) The issues surrounding their definition The first issue that one inevitably encounters in examining amphibious operations is the ambiguity surrounding their definition. Without a uniform understanding of the meaning of amphibious operations and of their associated concepts and terminologies, the actual execution of operations will likely be met with difficulties. Nevertheless, a uniform understanding or a “common language” for the associated concepts and terminologies has not been arrived at, not even in the United States, which has conducted many amphibious operations. -

The Idea of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective

Naval War College Review Volume 67 Article 6 Number 1 Winter 2014 The deI a of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective John B. Hattendorf Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Hattendorf, John B. (2014) "The deI a of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective," Naval War College Review: Vol. 67 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol67/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hattendorf: The Idea of a “Fleet in Being” in Historical Perspective THE IDEA OF a “FLEET IN BEING” IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE John B. Hattendorf he phrase “fleet in being” is one of those troublesome terms that naval his- torians and strategists have tended to use in a range of different meanings. TThe term first appeared in reference to the naval battle off Beachy Head in 1690, during the Nine Years’ War, as part of an excuse that Admiral Arthur Herbert, first Earl of Torrington, used to explain his reluctance to engage the French fleet in that battle. A later commentator pointed out that the thinking of several Brit- ish naval officers ninety years later during the War for American Independence, when the Royal Navy was in a similar situation of inferior strength, contributed an expansion to the fleet-in-being concept. -

Carriers and Amphibs: Shibboleths of Sea Power John T

Carriers and Amphibs: Shibboleths of Sea Power John T. Kuehn Journal of Advanced Military Studies, Volume 11, Number 2, 2020, pp. 106-118 (Article) Published by Marine Corps University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/796346/summary [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 02:38 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Carriers and Amphibs Shibboleths of Sea Power John T. Kuehn, PhD Abstract: This article argues that American naval force packages built around aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships no longer serve maritime security interests as effectively as in the past. It further claims that the current com- mitment in the published maritime strategy of the United States to the twin shibboleths of “carriers and amphibs” comes from a variety of attitudes held by senior decision makers and military leaders. This commitment betrays both cultural misunderstanding or even ignorance of seapower—“sea blindness”—as well as less than rational attachments to two operational capabilities that served the United States well in the past, but in doing so engendered emotional com- mitments that are little grounded in the facts. Keywords: aircraft carrier, amphibious readiness group, U.S. Navy, U.S. Ma- rine Corps, sea blindness, maritime security Shibboleth—A catchword; slogan1 hen typing “U.S. Navy status” into a search engine these days, one quickly learns that only two specific ship types are tracked on this Wsite and characterized as underway—“carriers” and “amphibs.” There are no submarines listed in this overview, no destroyers, no littoral com- John T. -

From Sea Power to Cyber Power Learning from the Past to Craft a Strategy for the Future

From Sea Power to Cyber Power Learning from the Past to Craft a Strategy for the Future By KRIS E. BARCOMB U.S. Navy cryptologic technicians preview Integrated System for Language Education and Training program at Center for Language, Regional Expertise, and Culture, Pensacola, Florida U.S. Navy (Gary Nichols) 78 JFQ / issue 69, 2 nd quarter 2013 ndupress.ndu.edu BARCOMB Naval strength involves, unquestionably, the possession of strategic points. —Alfred Thayer Mahan lfred Thayer Mahan saw the both economic growth and security akin to and overcome resource constraints: “The ocean for what it is. While it Mahan’s approach to sea power a century ago. search for and establishment of leading prin- spans the globe and covers a ciples—always few—around which consider- A predominant portion of the A Mahanian Approach to Cyberspace ations of detail group themselves, will tend to Earth, not all parts of it are equally impor- Mahan did not view the Navy as an reduce confusion of impression to simplicity tant. Mahan offered a focused naval strategy end unto itself, but as a key component of and directness of thought, with consequent in an era when America was struggling to the larger economic welfare of the Nation. facility of comprehension.”3 In accordance define itself as either isolated from, or an He tied the very existence of the Navy to with these two principles, this article identi- integral part of, the larger international com- commerce when he wrote, “The necessity of fies seven strategic points of concentration munity. The force structure of the U.S. -

Abstract JULIAN CORBETT and the DEVELOPMENT of a MARITIME

Abstract JULIAN CORBETT AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF A MARITIME STRATEGY by SAMUEL E. ROGERS NOVEMBER, 2018 Director: DR. WADE G. DUDLEY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Sir Julian Corbett (1854-1922) is one of the two most influential theorists of sea power. He defined maritime operations, limited war, and our understanding of the “British Way of War,” while also foreshadowing the Great War at Sea. Corbett’s lasting theoretical contributions to strategic thought are captured in Some Principles of Maritime Strategy (1911). It remains a centerpiece of military and international relations theory and continues to be studied in professional military education alongside Thucydides, Sun Tzu, Antoine-Henri Jomini, Carl von Clausewitz, and Alfred Thayer Mahan. Corbett’s influential theories were shaped by multiple influences, including Mahan, Corbett’s own study of British sea power, his reading and understanding of Clausewitz’s On War, and Admiral John Fisher’s naval revolution at the turn of the twentieth century. While Mahan linked sea power with national power, Corbett illuminated this relationship and displayed a keen understanding, developed through his own historical study, of the limits of sea power, and war more broadly, as an instrument of national policy. His influential theory on the role of sea power in the geopolitical context of the European balance of power at the turn of the twentieth century is a clear reflection of Britain’s rapidly changing strategic environment and the equally rapid changes in military technology. Heavily influenced by Admiral Fisher, Corbett, building on the work of Mahan and military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, defined maritime strategy, limited war, command of the sea, and, at the height of the British Empire, laid the ground work for understanding a “British way of war.” Corbett was first and foremost a historian and a professional military educator. -

Sea Power As a Strategic Domain by ME6 Khoo Kok Giok

features 1 Sea Power As A Strategic Domain by ME6 Khoo Kok Giok Abstract: The author focuses on the unique characteristics of sea power and its strategic utility. In this essay, he defines sea power with reference to Alfred Thayer Mahan, an American historian and naval officer who was an expert on sea power in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He then discusses the characteristics of sea power, its strengths and limitations in the peace to war continuum and its contributions to the Diplomatic, Informational, Military and Economic (DIME) instruments of national power. He highlights that in some cases, sea power is the strategic tool of choice while in others, it is merely an enabler. He goes on to argue that sea power has limitations to be qualified as a strategic domain on its own. In his opinion, the culmination of land-sea-air powers into a combined military power provides countries with better flexibility and options to employ military forces to meet strategic objectives. He concludes that military power, instead of land-air-sea power in solation, is better qualified as a strategic domain. Keywords: Sea Power; Independent; Extension; Capability; Influence INTRODUCTION Naval history dates back to the 5th century BC Nations rely on all available means to attain their under the Achaemenid Empire against Greek and 3 national objectives. These means are instruments of Egyptian threats. The Southern Song dynasty built a national power, namely Diplomatic, Informational, navy to safeguard its prosperity derived from coastal Military and Economic (DIME). Power represents the commerce.4 More recently, the British Empire, with a ability to influence behaviours of others or events in modest army, was founded on sea power.5 The Royal a manner to support one’s own objectives.1 Military Navy was one of the world’s most powerful navy, power, under the DIME framework, consists of land positioning Britain as the dominant world power from power, naval power and air power, skilfully employed the 17th century to World War II (WWII). -

Sea Power and American Interests in the Western Pacific

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. Sea Power and American Interests in the Western Pacific David C. Gompert C O R P O R A T I O N NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE Sea Power and American Interests in the Western Pacific David C. -

Some Principles of Cyber Warfare Using Corbett to Understand War in the Early Twenty–First Century

Corbett Paper No 19 Some Principles of Cyber Warfare Using Corbett to Understand War in the Early Twenty–First Century Richard M. Crowell The Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies January 2017 Some Principles of Cyber Warfare Using Corbett to Understand War in the Early Twenty–First Century Richard M. Crowell Key Points: Corbett’s theory of maritime warfare is used to illustrate how forces that move through cyberspace, content and code, have similar characteristics to forces moving through the maritime domain: fluidity of movement, omni–directional avenues of approach and the necessity to make shore (reach a human or machine destination) to be useable. • The relationship between the information environment (IE) and cyberspace as a key part of information-age war is described with a particular focus on how decision- making and control of machines takes place at the nexus of the dimensions of the IE. • The use, and rapid adaptation of, cyber force to influence human decision-making and compel machines to work independent of their owner’s intent is explored. • Cyberspace and cyber warfare are defined in ways that provide commanders, subordinates, and political leaders with a common framework. • Principles of cyber warfare are presented with examples from recent conflicts to illustrate the concepts of cyber control, cyber denial, and disputed cyber control. Dick Crowell is an associate professor in the Joint Military Operations Department at the US Naval War College. He specializes in information operations and cyberspace operations. A retired US Navy pilot, he served at sea and ashore for thirty years. He is a senior associate of the Center on Irregular Warfare and Armed Groups (CIWAG) and founding member of the Center for Cyber Conflict Studies (C3S). -

Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: a Chinese Dream

Becoming a Great “Maritime Power”: A Chinese Dream Rear Admiral Michael McDevitt, USN (retired) June 2016 Distribution unlimited This report was made possible thanks to a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation. SRF Grant: 2014-0047. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Photography Credit: Chinese carrier Liaoning launching a J-15. PLAN photo. https://news.usni.org/2014/06/09/chinese-weapons-worry-pentagon. Approved by: June 2016 Dr. Eric Thompson, Vice President CNA Strategic Studies Copyright © 2016 CNA Abstract In November 2012, then president Hu Jintao declared that China’s objective was to become a strong or great maritime power. This report, based on papers written by China experts for this CNA project, explores that decision and the implications it has for the United States. It analyzes Chinese thinking on what a maritime power is, why Beijing wants to become a maritime power, what shortfalls it believes it must address in order to become a maritime power, and when it believes it will become a maritime power (as it defines the term). The report then explores the component pieces of China’s maritime power—its navy, coast guard, maritime militia, merchant marine, and shipbuilding and fishing industries. It also addresses some policy options available to the U.S. government to prepare for—and, if deemed necessary, mitigate— the impact that China’s becoming a maritime power would have for U.S. interests. i This page intentionally left blank. ii Executive Summary In late 2012 the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party announced that becoming a “maritime power” was essential to achieving national goals. -

From Solid Shot to Tomahawk: the Development of American Naval Policy from the Early Republic to the Present

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 From solid shot to tomahawk: The development of American naval policy from the early republic to the present Scott E. Doxtator The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Doxtator, Scott E., "From solid shot to tomahawk: The development of American naval policy from the early republic to the present" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8832. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8832 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. fOhL ,J]i} Maureen and Mike JVIANSFIELD LIBRARY Tlie University of jM O N X A -N A Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check '*Yes" or "Vo" and provide sigfiaiure** Yes, I grant permission l / No, I do not grant permission _____ Author's Signature Date hl-ZX^I no Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

Corbett: a Man Before His Time

CORBETT: A MAN BEFORE HIS TIME Lieutenant Commander Ian C.D. Moffat Directorate of Defence Analysis 4-2 (DDA 4-2) Director General Strategic Planning Department of National Defence INTRODUCTION The Lacedaemonians now sent to the fleet to Cnemus three commissioners - Timocrates, Brasidas, and Lycophron - with orders to prepare to engage again with better fortune, and not be driven from the sea by a few vessels; for they could not at all account for their discomfiture, the less so as it was their first attempt at sea; and they fancied that it was not that their marine was so inferior, but that there had been misconduct somewhere, not considering the long experience of the Athenians as compared with the little practice which they had had themselves.1 Whosoever commands the sea commands the trade; whosoever commands the trade of the world commands the riches of the world, and consequently the world itself. - Sir Walter Raleigh2 From the advent of the first sea going vessel, ships have been targets for other rangers upon the sea. When governments went to war, it was an obvious extension of battle that the action would be extended to the sea between vessels of the belligerents. From the Greeks, and even before, the objective of navies has been to target the opposing side’s ships. This permeated the strategies of seafaring countries for centuries, and was chronicled in the histories written by sailors and politicians from Homer onward. The sailors in particular, when writing their memoirs, concentrated on great battles at sea and the tactics employed to attain the dramatic victories for which they had become famous.