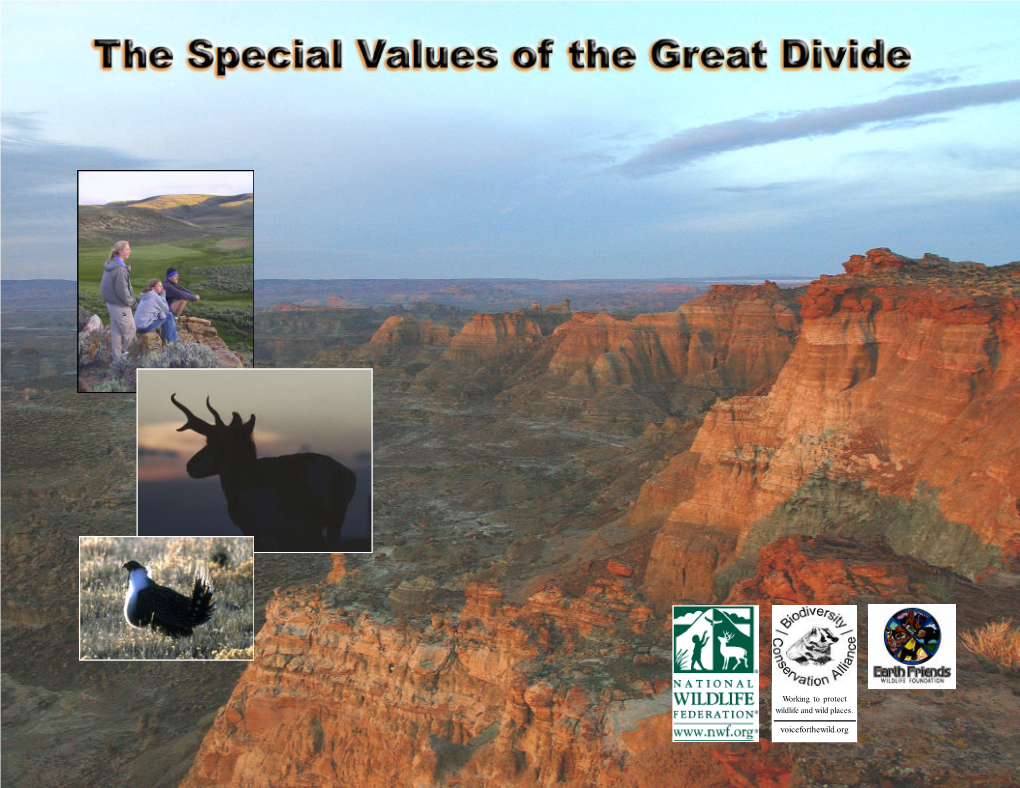

The Special Values of the Great Divide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 5 of the 2020 Antelope, Deer and Elk Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Antelope, 2020 Deer and Elk Hunting Regulations Don't forget your conservation stamp Hunters and anglers must purchase a conservation stamp to hunt and fish in Wyoming. (See page 6) See page 18 for more information. wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS Access on Lands Enrolled in the Department’s Walk-in Areas Elk or Hunter Management Areas .................................................... 4 Hunt area map ............................................................................. 46 Access Yes Program .......................................................................... 4 Hunting seasons .......................................................................... 47 Age Restrictions ................................................................................. 4 Characteristics ............................................................................. 47 Antelope Special archery seasons.............................................................. 57 Hunt area map ..............................................................................12 Disabled hunter season extension.............................................. 57 Hunting seasons ...........................................................................13 Elk Special Management Permit ................................................. 57 Characteristics ..............................................................................13 Youth elk hunters........................................................................ -

VGP) Version 2/5/2009

Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS (VGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act (CWA), as amended (33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.), any owner or operator of a vessel being operated in a capacity as a means of transportation who: • Is eligible for permit coverage under Part 1.2; • If required by Part 1.5.1, submits a complete and accurate Notice of Intent (NOI) is authorized to discharge in accordance with the requirements of this permit. General effluent limits for all eligible vessels are given in Part 2. Further vessel class or type specific requirements are given in Part 5 for select vessels and apply in addition to any general effluent limits in Part 2. Specific requirements that apply in individual States and Indian Country Lands are found in Part 6. Definitions of permit-specific terms used in this permit are provided in Appendix A. This permit becomes effective on December 19, 2008 for all jurisdictions except Alaska and Hawaii. This permit and the authorization to discharge expire at midnight, December 19, 2013 i Vessel General Permit (VGP) Version 2/5/2009 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 William K. Honker, Acting Director Robert W. Varney, Water Quality Protection Division, EPA Region Regional Administrator, EPA Region 1 6 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, 2008 Signed and issued this 18th day of December, Barbara A. -

2020 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2 MISSION + BOARD MEMBERS AND STAFF 7 BOARD PROJECTS 3 BUDGET BREAKDOWN + BLOCK GRANTS 8–9 MEDIA, MARKETING & PUBLIC RELATIONS 4 EVENT GRANTS + EVENT RECRUITMENT 10 TRAVEL IMPACT STUDIES 5 COMMITTEES & BOARDS + STRATEGIC PLAN 11 2019 TRAVEL IMPACTS 6 R.E.A.C.H. AWARDS + TOURISM AMBASSADORS EXPLOREWY.COM OUR BOARD MEMBERS & STAFF MISSION: FRONT ROW BACK ROW NOT PICTURED LINDA MCGOVERN MARK LYON JANET HARTFORD TO ENHANCE THE Board Member Board Vice-Chair Board Member BRIDGET RENTERIA ERIKA LEE-KOSHAR DOMINIC WOLF ECONOMYOF Board Chair Board Member Board Member SWEETWATER JENISSA MEREDITH KIM STRID LUCY DIGGINS-WOLD COUNTY BY Executive Director Board Member Tour Guide ATTRACTING AND ANGELICA WOOD DEVON BRUBAKER GRACE BANKS RETAINING Board Member Board Treasurer Visitor Assistant STACY COLVIN GREG BAILEY Board Secretary VISITORS. Board Member The lodging tax was originally approved by Sweetwater County voters in 1991 at 2%. Sweetwater CHEZNEY GOGLIO County voters approved increasing the lodging tax to Marketing Assistant 3% in 2014 and 4% in 2018 with over 80% support. LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION. In April 2020, Sweetwater County Travel and Tourism relocated their office to 1641 Elk Street and opened the “Explore Rock Springs and Green River, WY Visitor Center.” Elk Street (Hwy 191) is the perfect location to offer information and encourage travelers to spend more time in Rock Springs and Green River as they travel to and from Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. 2 BUDGET LODGING TAX BREAKDOWN COLLECTION FISCAL YEAR TOTAL -

Wilderness Study Areas

I ___- .-ll..l .“..l..““l.--..- I. _.^.___” _^.__.._._ - ._____.-.-.. ------ FEDERAL LAND M.ANAGEMENT Status and Uses of Wilderness Study Areas I 150156 RESTRICTED--Not to be released outside the General Accounting Wice unless specifically approved by the Office of Congressional Relations. ssBO4’8 RELEASED ---- ---. - (;Ao/li:( ‘I:I)-!L~-l~~lL - United States General Accounting OfTice GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Resources, Community, and Economic Development Division B-262989 September 23,1993 The Honorable Bruce F. Vento Chairman, Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands Committee on Natural Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: Concerned about alleged degradation of areas being considered for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (wilderness study areas), you requested that we provide you with information on the types and effects of activities in these study areas. As agreed with your office, we gathered information on areas managed by two agencies: the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLN) and the Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service. Specifically, this report provides information on (1) legislative guidance and the agency policies governing wilderness study area management, (2) the various activities and uses occurring in the agencies’ study areas, (3) the ways these activities and uses affect the areas, and (4) agency actions to monitor and restrict these uses and to repair damage resulting from them. Appendixes I and II provide data on the number, acreage, and locations of wilderness study areas managed by BLM and the Forest Service, as well as data on the types of uses occurring in the areas. -

Assessment of Colorado's Wilderness Areas

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2011 Assessment of Colorado’s Wilderness Areas: Manager Perceptions and Remoteness Modeling Gary D. Vaughn Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Vaughn, Gary D., "Assessment of Colorado’s Wilderness Areas: Manager Perceptions and Remoteness Modeling" (2011). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 1096. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1096 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSMENT OF COLORADO’S WILDERNESS AREAS: MANAGER PERCEPTIONS AND REMOTENESS MODELING by Gary D. Vaughn A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Recreation Resource Management Approved: ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Christopher A. Monz Dr. Mark W. Brunson Major Professor Committee Member ________________________ ________________________ Dr. Christopher M. U. Neale Dr. Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2011 ii Copyright © Gary D. Vaughn 2011 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Assessment of Colorado’s Wilderness Areas: Manager Perceptions and Remoteness Modeling by Gary D. Vaughn, Master of Science Utah State University, 2011 Major Professor: Dr. Christopher Monz Department: Environment & Society This study assessed visitor use levels and resource and social conditions in wilderness areas across the State of Colorado using existing and collected spatial data. -

Mineral Resources of the Ferris Mountains Wilderness Study Area, Carbon County, Wyoming

Mineral Resources of the Ferris Mountains Wilderness Study Area, Carbon County, Wyoming &£ %r^ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1757-C .r WYOMING Chapter C Mineral Resources of the Ferris Mountains Wilderness Study Area, Carbon County, Wyoming By MITCHELL W. REYNOLDS U.S. Geological Survey JOHN T. NEUBERT U.S. Bureau of Mines U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1757 MINERAL RESOURCES OF WILDERNESS STUDY AREAS- SOUTHERN WYOMING DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1988 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section U.S. Geological Survey Federal Center Box 25425 Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reynolds, Mitchell W. Mineral resources of the Ferris Mountains Wilderness Study Area, Carbon County, Wyoming. (Mineral resources of wilderness study areas southern Wyoming ; ch. C) (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 1757-C) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.3:1757-C 1. Mines and mineral resources Wyoming Ferris Mountains Wilderness. 2. Ferris Mountains Wilderness (Wyo.) I. Neubert, John T. II. Series. III. Series: U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 1757-C. QE75.B9 no. 1757-C 557.3 s [553'.09787'86] 87-600485 [TN24.W8] STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Areas The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (Public Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines to conduct mineral surveys on certain areas to determine the mineral values, if any, that may be present. Results must be made available to the public and be submitted to the President and the Congress. -

Appendix C - Roadless Areas

Appendix C - Roadless Areas Purpose The purpose of this appendix is to describe roadless areas and the analysis factors used in evaluating individual roadless areas on the Routt National Forest. It includes a description of the physical and biological features, primitive recreation and education opportunities, resources, and present management situation for each area. Background Roadless Area Review and Evaluation In 1970, the Forest Service studied all administratively designated primitive areas and inventoried and reviewed all roadless areas in the National Forest System greater than 5,000 acres. This study was known as the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE). RARE was halted in 1972 due to legal challenge. RARE identified 711,043 acres of roadless area on the Routt National Forest. In 1977, the Forest Service began another nation-wide Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE II) to identify roadless and undeveloped areas within the National Forest System that were suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. Twenty nine areas, totalling 566,756 acres, were inventoried on the Routt National Forest (including the Middle Park Ranger District of the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest). As a result of RARE II, four areas on the forest - Williams Fork, St. Louis Peak, Service Creek, and Davis Peak - were administratively designated as Further Planning Areas (FPA). This further planning area designation meant that more information was needed before the Forest Service would recommend any of these areas to Congress for wilderness designation. In January 1979, the Forest Service issued nationally a Final Environmental Impact Statement documenting a review of 62 million acres of roadless and undeveloped areas within the 191-million-acre National Forest System. -

Mineral Occurrence and Development Potential Report Rawlins Resource

CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Purpose of Report ............................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Lands Involved and Record Data ....................................................................................1-2 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF GEOLOGY ...............................................................................................2-1 2.1 Physiography....................................................................................................................2-1 2.2 Stratigraphy ......................................................................................................................2-3 2.2.1 Precambrian Era....................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2 Paleozoic Era ........................................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.1 Cambrian System...................................................................................2-3 2.2.2.2 Ordovician, Silurian, and Devonian Systems ........................................2-5 2.2.2.3 Mississippian System.............................................................................2-5 2.2.2.4 Pennsylvanian System...........................................................................2-5 2.2.2.5 Permian System.....................................................................................2-6 -

Draft Small Vessel General Permit

ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES, COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAM PUBLIC NOTICE The United States Environmental Protection Agency, Region 5, 77 W. Jackson Boulevard, Chicago, Illinois has requested a determination from the Illinois Department of Natural Resources if their Vessel General Permit (VGP) and Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) are consistent with the enforceable policies of the Illinois Coastal Management Program (ICMP). VGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non-recreational vessels greater than or equal to 79 ft. in length. sVGP regulates discharges incidental to the normal operation of commercial vessels and non- recreational vessels less than 79 ft. in length. VGP and sVGP can be viewed in their entirety at the ICMP web site http://www.dnr.illinois.gov/cmp/Pages/CMPFederalConsistencyRegister.aspx Inquiries concerning this request may be directed to Jim Casey of the Department’s Chicago Office at (312) 793-5947 or [email protected]. You are invited to send written comments regarding this consistency request to the Michael A. Bilandic Building, 160 N. LaSalle Street, Suite S-703, Chicago, Illinois 60601. All comments claiming the proposed actions would not meet federal consistency must cite the state law or laws and how they would be violated. All comments must be received by July 19, 2012. Proposed Small Vessel General Permit (sVGP) United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) SMALL VESSEL GENERAL PERMIT FOR DISCHARGES INCIDENTAL TO THE NORMAL OPERATION OF VESSELS LESS THAN 79 FEET (sVGP) AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE NATIONAL POLLUTANT DISCHARGE ELIMINATION SYSTEM In compliance with the provisions of the Clean Water Act, as amended (33 U.S.C. -

Status of Plant Species of Special Concern in US Forest Service

Status of Plant Species of Special Concern In US Forest Service Region 4 In Wyoming Report prepared for the US Forest Service By Walter Fertig Wyoming Natural Diversity Database University of Wyoming PO Box 3381 Laramie, WY 82071 20 January 2000 INTRODUCTION The US Forest Service is directed by the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and internal policy (through the Forest Service Manual) to manage for listed and candidate Threatened and Endangered plant species on lands under its jurisdiction. The Intermountain Region of the Forest Service (USFS Region 4) has developed a Sensitive species policy to address the management needs of rare plants that might qualify for listing under the ESA (Joslin 1994). The objective of this policy is to prevent Forest Service actions from contributing to the further endangerment of Sensitive species and their subsequent listing under the ESA. In addition, the Forest Service is required to manage for other rare species and biological diversity under provisions of the National Forest Management Act. The current Sensitive plant species list for Region 4 (covering Ashley, Bridger-Teton, Caribou, Targhee, and Wasatch-Cache National Forests and Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area in Wyoming) was last revised in 1994 (Joslin 1994). Field studies by botanists with the Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Herbarium, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD), and private consulting firms since 1994 have shown that several currently listed species may no longer warrant Sensitive designation, while some new species should be considered for listing. Region 4 is currently reviewing its Sensitive plant list and criteria for listing. This report has been prepared to provide baseline information on the statewide distribution and abundance of 127 plants listed as “species of special concern” by WYNDD (Table 1) (Fertig and Beauvais 1999). -

1176 Miles from Omaha to Sacramento O N T R a C K S

RAILWAY AT DALE CREEK BRIDGE, WYOMING 69 18 Y, MA R D E E A E L N N Y E H E C E H Promontory Summit, Utah T Golden Spike Ceremony Ohmaha, NE NEWDRAFT Sacramento, CA 1869 - May 10th. - 1869 YoRK ! DRAFT GREAT EVENT ! RAIL ROAD FROM THE ATLANTIC TO THE PACIFIC GRAND OPENING t r a i n "dining saloon" ’ E a t i n s t y l e R A I L S w h i l e t r a v e l i n g T I C K E T S THE GREAT TRANS-CONTINENTAL ALL-RAIL ROUTE KID the tracks. -Business Men- - $ 1 1 1 FOR FIRST CLASS T a k e a d va n d a g e FACT 4 8 p e o p l e t o a c a r - HEATED CAR o f n e w ly o p e n e d - COMFORTABLE BEDS a s i a n m a r k e t s v i a fastest way to go coast to coast - no more wagon trains TRAINS TRAVELED c a l i f o r n i a - F O R T H I R d Almost M e n u $ 4 0 MPH CLASS TICKETS in 1869 - W O O D E N B E N C H E S - -Settlers!- Fried Salmon Steak ............................ 35c Boiled Ox Tongue with Tomato Sauce... 35c O N L Y A F E W I t ' s y o u r 1176 Miles from Omaha to Sacramento Pickled Lam’s Tongue.......................... -

Gold Panning and Dredging Information

Gold Panning and Dredging Information Dredging and Panning Specifications Please have a copy of your “Letter of Intent” with you when operating on the Medicine Bow National Forest. • Mechanized season of operation on the Medicine Bow National Forest is: July 01 to September 10 on all streams. This is to protect trout spawning habitat. • Hand panning is allowed outside. • High-banking is defined as “moving water from the stream channel via mechanical means to a location outside of the steam channel floor to process material for its gold content”. High-banking IS NOT excavating into the stream bank. • Excavating into the stream bank to obtain material for its gold content is PROHIBITED. Please stay within the boundaries of the stream channel floor or when high-banking, at least 100 feet outside of the stream channel floor. • If a hole is created while high-banking away from the stream channel, please fill in the hole before you leave the Medicine Bow National Forest. • If stream levels are low late in the summer, gold dredgers and panners may be required to keep their operations 300 feet apart to minimize stream turbidity. • Use small portable suction dredges with a suction hose intake of three (3) inches or less in diameter. • Use small portable suction dredges powered by 10 horsepower or less engines. • Only hand panning is allowed in any Class I water. Class I waters within the Medicine Bow National Forest are: 1. The main stem of the North Platte River from the mouth of Sage Creek (approximately 15 stream miles below Saratoga, Wyoming) upstream to the Wyoming/Colorado state line.