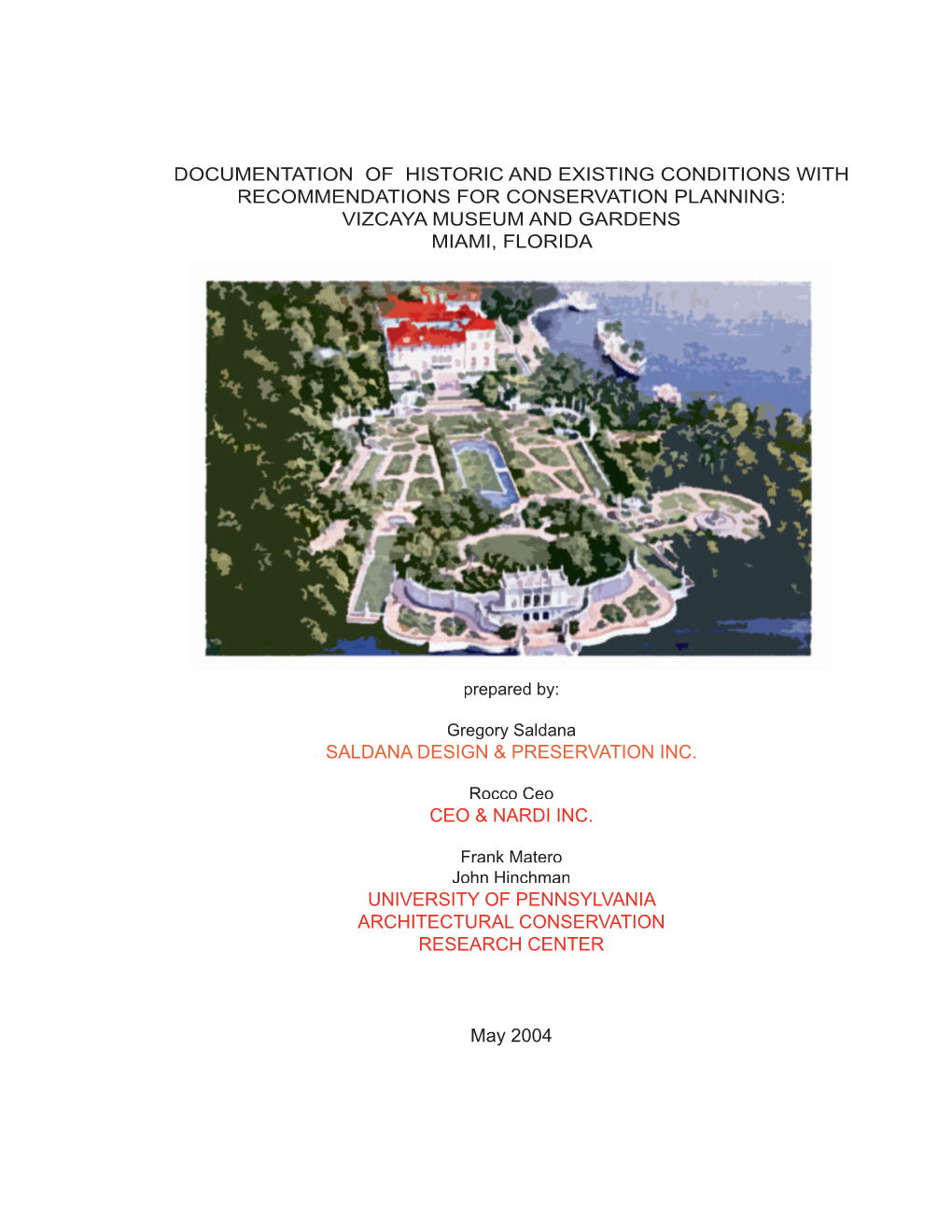

Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Miami, Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May/June 2019

Today’s Fern May/June 2019 Publication of the 100 Ladies of Deering, a philanthropic circle of the Deering Estate Foundation The 100 Ladies Again Undertake a Whirlwind Month Like the citizens of Sitges, Spain, the 100 Ladies of Deering are devoted to the preservation of a historic landmark once owned by Charles Deering. Our efforts to conserve and preserve this magniBicent estate located in our backyard, unites us with citizens of Sitges on the other side of the Atlantic. Those who went on our fundraising cruise in April experienced the small town of Sitges’ gratitude to the memory of the Town’s Adopted Son, Charles Deering. One hundred and ten years from the time Deering Birst visited Sitges, we were welcomed like long lost family with choral songs, champagne, and stories of the beloved adopted son’s vision, philanthropy and economic contributions. The stories we share are similar, like here in Cutler, Deering built an “architectural gem” in Sitges and Billed it at the time President Maria and husband David toast a very successful fundraiser with art by renowned artists. The town’s warm cruise to Spain…with side trips to Sitges and Tamarit. welcome given to us was inspiring because it demonstrates their deep “If we love, and we do, appreciation for Charles Deering’s vision and legacy which we both strive to what Charles Deering preserve. I highly encourage you to participate in any future trips where we seek to bequeathed us…If we further understand Charles Deering’s legacy, whether here in Miami, Chicago or consider it to be so Spain. -

Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History Daniel Peter Ott Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ott, Daniel Peter, "Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History" (2014). Dissertations. 1486. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2014 Daniel Peter Ott LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PRODUCING A PAST: CYRUS MCCORMICK’S REAPER FROM HERITAGE TO HISTORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JOINT PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY / PUBLIC HISTORY BY DANIEL PETER OTT CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Daniel Ott, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the result of four years of work as a graduate student at Loyola University Chicago, but is the scholarly culmination of my love of history which began more than a decade before I moved to Chicago. At no point was I ever alone on this journey, always inspired and supported by a large cast of teachers, professors, colleagues, co-workers, friends and family. I am indebted to them all for making this dissertation possible, and for supporting my personal and scholarly growth. -

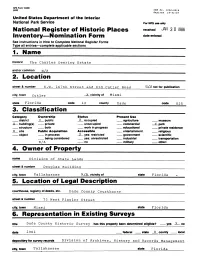

6. Representation in Existing Surveys

NFS Form 10-900 (3-82) OHB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register off Historic Places received JAN 3 0 1986 Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries — complete applicable sections _______________ 1. Name historic The Charles Peering Estate and or common N/A 2. Location street & number S.W. 167th Street and Old Cutler Road not for publication city, town Cutler _X_ vicinity of Miami state Florida code 12 county Dade code 025 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district _X _ public X occupied agriculture __ museum JL_ building(s) private unoccupied commercial ^K_park structure both work in progress educational private residence JL_ site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation N/A no military Other; 4. Owner off Property name Division of State Lands street & number Douglas Building city, town Tallahassee N/A vicinity of state Florida 5. Location off Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. street & number 73 West Flagler Street city, town Miami state Florida 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Dade County Historic Survey has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date J9'81 federal state X county local depository for survey records Division of Archives , History and Records Management city, town Tallahassee ____________ state Florida_____ 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site x good ruins ^ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Charles Deering Estate is one of the finest bayfront properties in Dade County. -

ROOTS in CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep

ROOTS IN CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep 1847-^1947 ROOTS IN CHICAGO One Hundred Years Deep 1847-1947 ^ch. Illl^^; i- ^'*k>.«,''''*!a An illustrated map of Chicago, 1847, with which have been combined historic developments leading up to and including the Chicago Fire of 1871. ^^ m .4 1. First McCormick Factory—1847 > ;**!!>*>>, 2. Old Fort Dearborn -1847 L^tim_^wr """ ,4. First Permanent School—1845] 5. Water Works-1854 13. First Court House—1835 .IIIIIIIIUIIIIIIIII! john mckee -JJ ^^^^J ^^^J ^^^^ ^W^^v^A^ V^^^^J ^^LAV ^^^M ^^1^1 ^^^AJ ^^^W ^^^V ^^^^m U-J^^-JS u"''-"--'''^ Cilaajij^ f.nU Infi ,1)1 M v3 ^- ••^ •c> c;^ '-a -.•^ ••••.>« tnick Theological Seminary Chicago Fire-1871 >,»ii)iiiinmiiiiiin!i HI I'nTiTn •'•••••ll 2 fe n^ir • ••I m " ™ 11 Enlarged Factory—1871 Prefiace THIS YEAR IS THE 100th Anniversary of an event which has played an important part in the building of Chi cago. In late summer of 1847 my grandfather, Cyrus Hall McCormick, came to Chicago to manufacture an improved model of the reaper he had invented and publicly demonstrated sixteen years earlier in Virginia. The little reaper plant which he founded, and de veloped through the years with the assistance of his two brothers, is now represented in the Chicago area by six International Harvester Company factories, a manufacturing research center, a central school for Harvester personnel, a Harvester printing plant, gen eral offices, and a number of motor truck sales branches. More than 30,000 Harvester men and women are now employed in Chicago. It is fitting at this time to pay tribute to the man whose genius laid the groundwork for Harvester's ex tensive operations in Chicago as well as in the rest of the world. -

The Marine Garden at Villa Vizcaya Miami, Florida : a Management and Interpretation Analysis

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2004 The Marine Garden at Villa Vizcaya Miami, Florida : A Management and Interpretation Analysis Jorge M. Danta University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Danta, Jorge M., "The Marine Garden at Villa Vizcaya Miami, Florida : A Management and Interpretation Analysis" (2004). Theses (Historic Preservation). 47. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/47 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2004. Advisor: Randall F. Mason This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/47 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marine Garden at Villa Vizcaya Miami, Florida : A Management and Interpretation Analysis Abstract This graduate thesis analyzed the historical and current management of Vizcaya Museum and Gardens. This analysis was aimed at investigating the causes and circumstances that led to the physical deterioration of the Marine Garden. Through this examination two main goals were set. Goal one, the reassessment of the historic values specific ot the gardens and Marine Garden and goal two, the provision of recommendations for the management, maintenance and interpretation for the gardens and Marine garden specifically. Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2004. Advisor: Randall F. Mason This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/47 This Thesis is dedicated to Mr. -

Roman Altar & Lombardic Columns

Roman Altar & Lombardic Columns VIZCAYA MUSEUM AND GARDENS, MIAMI, FL SERVICES PERFORMED Between 1914 and 1916, agricultural industrialist and one of the founders of the International Harvester Conservation Treatments Company, James Deering, built his European-inspired winter home on Biscayne Bay in Miami. This Research & Documentation property, Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, is now a National Historic Landmark. The formal gardens Surveys & Condition Assessments include an outstanding collection of statuary and objects dating back to antiquity. These include a 2nd century Roman altar, formally in the Borghese collection, installed beside two 10th century Lombardic carved marble columns in the Fountain Garden. The garden was ooded in the storm surge of Hurricane Wilma in 2005 and both artifacts were subjected to extensive salt contamination as well as damage from ying and oating debris. We were contracted to restore the losses, desalinate, and clean the fragile ancient marbles. Each was extensively rinsed with clean, ltered water until salt readings were reduced to acceptable levels. Biological growth and soiling were removed by detergent washes and the use of biocides to remove deposits that still contained salts. Failed previous synthetic lls were removed and the voids were cleaned. Losses, including a part of the decorative band on the capital of one column, were replaced with lime-based mortars or stone dutchman repairs according to the client’s goals. Work was performed during treatment of more than 30 statues damaged in the hurricane. All work was documented in a treatment report submitted upon completion of the project. MORE INFORMATION: https://evergreene.com/projects/roman-altar/ 253 36th Street, Suite 5-C | Brooklyn, New York, 11232 | (212) 244 2800 | evergreene.com. -

Vizcaya by ADAM G

Vizcaya By ADAM G. ADAMS The text of the plaque just unveiled is:* JAMES DEERING 1859-1925 James Deering of Chicago, a founder of the International Harvester Company, a pioneer developer of South Florida, noted connoisseur of the fine arts and distinguished philanthropist, built Vizcaya and lived there from 1916 until his death in 1925. In the buildings and gardens of Vizcaya, an expression of the classic Mediterranean spirit of Italy and France, unique in America, Mr. Deering brought to- gether many rare European art treasures, and inspired the designs which combine them so skillfully with local materials. Marion Deering McCormick and Barbara Deering Danielson, his nieces, made Vizcaya available to Dade County as a public art museum November 1952. The purpose of this plaque is to keep green the memory of the persons and events which have made possible this magnificent heritage of Dade County. The physical property is in wonderful condition. During the thirty years since Mr. Deering's death his heirs have kept constant vigilance against the ravages of time. And the Dade County Park Department continues careful maintenance and operation as a public museum. But it is now a public place! Let's put our fingers on the throbbing pulse of a great private home of an artistic, perfectionist bachelor millionaire. Mrs. C. J. Adair, for 35 years the housekeeper, arrived in February 1917, two months after Mr. Deering. Her staff numbered thirty-two, among them two French chefs, four butlers, four house men, and six house maids. All the maid's uniforms were made in the house, as well as the men's summer whites. -

The Romance of the Reaper

The Romance Of The Reaper By Herbert Newton Casson The Romance Of The Reaper CHAPTER I THE STORY OF MCCORMICK THIS Romance of the Reaper is a true fairy tale of American life—the story of the magicians who have taught the civilised world to gather in its harvests by machinery. On the old European plan—snip—snip—snipping with a tiny hand-sickle, every bushel of wheat required three hours of a man’s lifetime. To-day, on the new American plan—riding on the painted chariot of a self-binding harvester, the price of wheat has been cut down to ten minutes a bushel. “When I first went into the harvest field,” so an Illinois farmer told me, “it took ten men to cut and bind my grain. Now our hired girl gets on the seat of a self-binder and does the whole business.” This magical machinery of the wheat-field solves the mystery of prosperity. It explains the New Farmer and the miracles of scientific agriculture. It accounts for the growth of great cities with their steel mills and factories. And it makes clear how we in the United States have become the best fed nation in the world. Hard as it may be for this twentieth century generation to believe, it is true that until recently the main object of all nations was to get bread. Life was a Search for Food—a desperate postponement of famine. Cut the Kings and their retinues out of history and it is no exaggeration to say that the human race was hungry for ten thousand years. -

WOTW-Miami Booklet Lowspreads

What’s Out There® Miami South Florida Dear What’s Out There Weekend Visitor, Welcome to What’s Out There Weekend Miami, organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF). The materials in this guide will tell you about the history and design of the places you can tour during this free event, the ninth in a series that we offer each year in cities and regions throughout the United States. Please keep this guide as a reference for future explorations of the greater Miami area’s significant landscapes. On April 12th and 13th, during What’s Out There Weekend Miami, residents and visitors have opportunities to discover more than thirty of the region’s publicly accessible landscapes through free, expert-led tours. Miami and South Florida’s landscape legacy extends from its Spanish Colonial roots to the present, where strong Modernist, Beaux Arts, and Mediterranean design concepts from Europe and the Eastern U.S. are expressed in unique gardens, parks, plazas, estates, and streetscapes. Explore Miami and South Florida landscapes through tours that include entertaining anecdotes and intriguing stories about city shaping, landscape Photo courtesy The Biltmore Hotel architecture, and the city’s design history. The tours reveal the story behind these valued places and the individuals who designed or made them. What’s Out There Weekend dovetails with the Web-based What’s Out There, the nation’s most comprehensive searchable database of historic designed landscapes. The database currently features more than 1,500 sites, 10,000 images, and 750 designer profiles. In 2013What's Out There was optimized for iPhones and similar handheld devices, and includes a new feature – What's Nearby – a GPS-enabled function that locates all landscapes in the database within a 25-mile radius of any given location. -

Charles G. Dawes Archive

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Library, Evanston, Illinois 60208-2300 Charles G. Dawes Archive Biography: Charles Gates Dawes (1865-1951), prominent in U.S. politics and business, served as Comptroller of the Currency (1898-1901), director of the Military Board of Allied Supply (1918-1919), and first director of the Bureau of the Budget (1921). He received a Nobel Peace Prize as chairman of the Reparations Commission which restructured Germany's economy and devised a repayment plan (1924). He was elected Vice-President (1925- 1929), and appointed ambassador to England (1929-1931) and chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932). Charles and his brothers founded Dawes Brothers Incorporated. Dawes formed the Central Trust Co. in Chicago (1902), guided its successor banks, and was influential in Chicago business, politics, and philanthropy until his death. Charles Gates Dawes was born and educated in Ohio. He married Caro Blymyer in 1889, practiced law, and incorporated a real estate business in Lincoln, Nebraska, before moving to Evanston, Illinois in 1895. He acquired utility companies and real estate in northern Illinois and Wisconsin; and in 1908, with his brothers Henry, Rufus, and Beman, formed Dawes Brothers Incorporated, to invest assets in banks, oil companies and real estate throughout the country. Various acquaintances who were prominent in political and industrial affairs trusted them to manage their investments as well. Other companies in which Charles Dawes and his brothers played leading roles included Chicago's Central Trust Co. and its successor banks and Pure Oil Company of Ohio. Dawes made significant philanthropic contributions to the Chicago metropolitan community. -

Historique De Case IH

Historique de Case IH 1831 La première moissonneuse est présentée avec succès à Steele's Tavern, par Cyrus Hall McCormick. Cette invention, et plus tard le râteau automatique de McCormick, permettront à un seul homme de couper près de 16 hectares en une seule journée, travail réalisé jusque là manuellement par 5 hommes. La moissonneuse et les initiatives de développement, de fabrication et de commercialisation de produits de McCormick sont considérées comme étant les principaux moteurs de la création de l’industrie du machinisme agricole dans le monde entier. 1834-1860 La société McCormick Harvesting Company est la première dans l’industrie du machinisme agricole à mettre en place un vaste système de garantie,un imposant système de vente soutenu par un réseau de filiales, sur tout le continent, par des campagnes publicitaires, des crédits pour l’achat de matériels et la réalisation gratuite de modifications sur les équipements. 1842 Jerome Increase Case (1819-1891) rapporte de Williamstown (Etat de New York) une batteuse rudimentaire et encombrante à Rochester, (Wisconsin). Là, il l'améliore et crée son entreprise. 1843 Jerome Case transfère son entreprise à Racine, (Wisconsin) sur les rives du Lac Michigan en raison de l'énergie hydraulique disponible. Il une usine de batteuses élémentaires, tout en apportant des améliorations à chaque nouveau modèle. 1847 Afin de suivre le développement à l’Ouest des Etats-Unis, McCormick transfère son usine à Chicago. L’usine de moissonneuses (Reaper Works) devient la plus grande du Midwest, et deviendra le site du siège social de la société International Harvester Company basée en plein cœur de Chicago. -

HARVESTER WORLD Vol

HARVESTER WORLD Vol. 22 May 1931 No. 5 THE MAN WITH THE HOE HAS STRAIGHTENED HIS BENT BACK AND COME INTO HIS OWN. HE HAS TAKEN POWER AND MACHINES, EVER MORE SAVING X 8 3 X OF TOIL AND LABOR, OUT AMONG X 8 3 X \CENTENNIAL THE NATURAL RESOURCES McCORMICK/ of t h e THAT ARE HIS BIRTHRIGHT AND REAPER SET UP THE NEW DOMAIN OF EN LIGHTENED AGRICULTURE. Keep out in front, Don't hesitate— Keep making calls/ And DEMONSTRATE I A GOOD SPRING TONIC Demonstrations spotlight the good points of a that machine to a great many other similar farm machine, influence selected prospects, and cause and operating conditions in his trade territory. orders to be signed. Frequently successful demonstrations induce Whenever a Harvester salesman or blockman the prospects to sign on the spot. And every or a McCormick-Deering dealer concludes a such result does much for the demonstrator. successful demonstration, he has automatically It proves effectively that an ounce of demon increased his ability to sell goods. And the more stration is worth considerably more than a he demonstrates and the more he improves his pound of talk in clinching sales. Such proof demonstration technique, the more successful peps him up and multiplies his confidence in the he will be in writing business. demonstration route to more sales. While a successful demonstration is building ' 'Demonstrations are the best sales tonic in the up a prospect's confidence in a machine, it is world for our own organization and for the stiffening the demonstrator's confidence in his dealer," declared Branch Manager C.