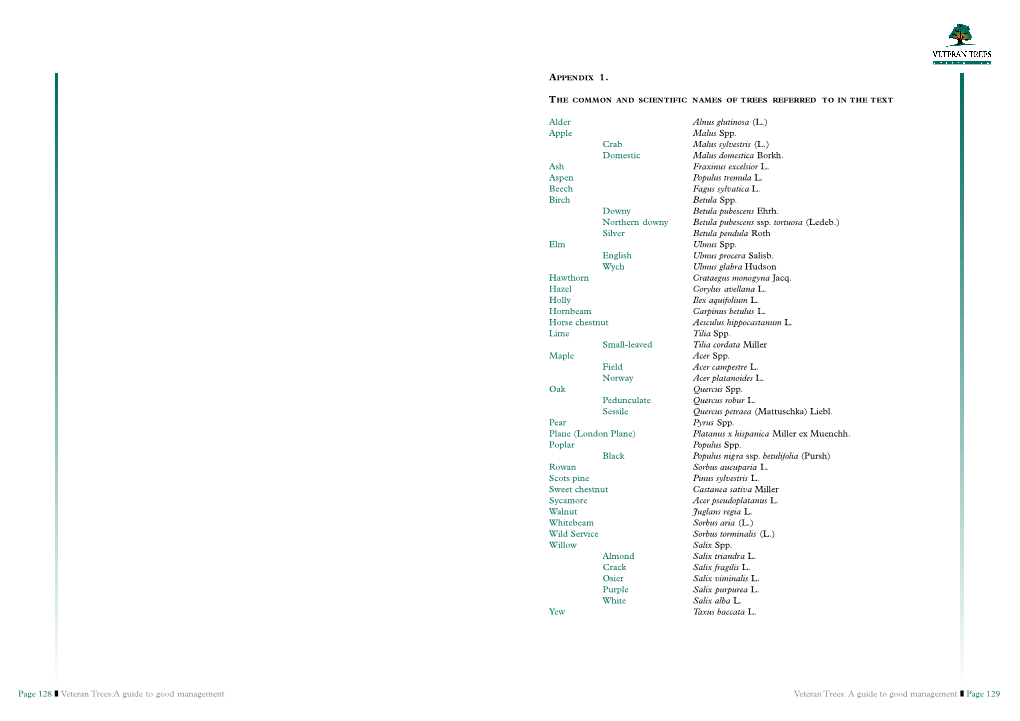

Veteran Trees: a Guide to Good Management Page 129 Alder Alnus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Recording and Information Generic Biodiversity Action Plan

Biological Recording and Information Generic Biodiversity Action Plan • Better informed policy & decision making • Avoidance of unnecessary damage to biodiversity • Effective targeting of scarce resources to best use • Compliance with statutory reporting requirements • Monitoring of programme effectiveness • Monitoring of short & mid term habitat & species trends • Important component of education & awareness raising Up to date accessible records are an essential starting point for nature conservation and the implementation of the biodiversity action plan process. Without knowledge about the location and quantity of different habitats and species, both in the past and present, declines cannot be detected and conservation management cannot be focused to achieve effective targeting of scarce resources to best use . In addition, monitoring is vital in order to determine whether conservation management is working, demonstrating whether it is maximising biodiversity or reversing any previous population declines, thus avoiding unnecessary damage to biodiversity and allowing discrete monitoring of programme effectiveness . It is essential not only to give users access to the data that already exist but also to improve the quantity, quality and relevance of biodiversity data. Information needs to be up-to-date and trustworthy, as complete as possible, accurate and rapidly accessible. Where required it must be interpreted and evaluated so that users can judge what significance should be attached to it. This provides us with a focus point for the collation and management of data relating to the wildlife of Worcestershire. The pooling of data from a number of sources provides a greater overall resource for the County of high quality, well presented, and clearly understandable data relating to, for example, species occurrences and distributions for a given area. -

Various Stuff!

Various Stuff! Peter Thurman [email protected] Some Notes On: • The Tenacity of Trees • Some Benefits of Trees • Trees and Culture • Some Threats to Trees + Some Solutions • Biosecurity • Biodiversity • Tree Planting & Aftercare • Some Trees to Avoid • New trees to Consider? The Tenacity of Trees Coping & Helping with Soil Erosion Moving Concrete St Jose, USA Chinese privet (Ligustrum lucidum) Clipped hard every 4 years “Planting the Space” Orvieto, Italy Proliferating root growth Tetrameles nudiflora at Ta Prohm Temple in Cambodia Hong Kong Chinese banyan Ficus microcarpa Looking for oxygen and trying to get rid of carbon dioxide but seeking moisture in the paving joints - Hong Kong Tolerance of Very Low Ground and Air Temperatures [here = Bavaria] Long Living/Resilience Ancient Olive [Olea europaea] tree in Montenegro High wind / exposure Trees adapt, evolve and survive – Phenotypic and Genotypic adaptation “Base of a Wine Glass root systems” ...but not always... Benefits Why do we plant trees? Aesthetics Their attractive visual appearance – Decoration and Ornament Oxygen! The Air that we Breathe Architecture and Landscape Design Framing, Screening, Shelter, Unifying, Softening, Space Division, Green Mass and Infrastructure Engineering SUDS, Canopy Cover, Climate and Pollution Amelioration, Soil Stabilisation, Erosion Control Cultural/Historical/Educational Linking the past with the present and the future, Social Traditions Wildlife Biodiversity and Flora, Fauna & Habitat Conservation Well Being and Recreation Contributing to the Mental and Physical Health & Happiness of humans - Biophilia Economic Added-value to properties and districts, Energy conservation, Bio-Fuels, Timber and many other Bi-products Aesthetics Marks Hall Gardens and Arboretum, Essex Do people notice plant form more than flowers? “Imagine if trees gave off Wi-Fi signals… We would be planting so many. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Insectos 2020 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos insectos 2020 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20202): Os nomes galegos dos insectos. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga /wp!content/up oads/achave_osnomesga egosdos"insectos"2020.pd# Fotografía: abella (Apis mellifera ). Autor: Jordi Bas. $sta o%ra est& su'eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a%erto( con reco)ecemento da autor*a e sen o%ra derivada nin usos comerciais. +esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.org/ icences/%,!nc-nd/-.0/deed.g . 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont n este documento Na primeira edición deste recurso léxico (2018) fornecéronse denominacións para as especies máis coñecidas de insectos galegos (e) ou europeos, e tamén para algúns insectos exóticos (mostrados en ám itos divulgativos polo seu interese iolóxico, agr"cola, sil!"cola, médico ou industrial, ou por seren moi comúns noutras áreas xeográficas)# Nesta segunda edición (2020) incorpórase o logo da $%a!e ao deseño do documento, corr"xese algunha gralla, reescr" ense as notas introdutorias e engádense algunhas especies e algún nome galego máis# &n total, ac%éganse nomes galegos para 89( especies de insectos# No planeta téñense descrito aproximadamente un millón de especies, e moitas están a"nda por descubrir# Na )en"nsula * érica %a itan preto de +0#000 insectos diferentes# Os nomes das ol oretas non se inclúen neste recurso léxico da $%a!e, foron o xecto doutro tra allo e preséntanse noutro documento da $%a!e dedicado exclusivamente ás ol oretas, a!ela"ñas e trazas . Os nomes galegos -

Managing Deadwood in Forests and Woodlands

Practice Guide Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands Practice Guide Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands Jonathan Humphrey and Sallie Bailey Forestry Commission: Edinburgh © Crown Copyright 2012 You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team at The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or e-mail [email protected]. This publication is also available on our website at: www.forestry.gov.uk/publications First published by the Forestry Commission in 2012. ISBN 978-0-85538-857-7 Jonathan Humphrey and Sallie Bailey (2012). Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands. Forestry Commission Practice Guide. Forestry Commission, Edinburgh. i–iv + 1–24 pp. Keywords: biodiversity; deadwood; environment; forestry; sustainable forest management. FCPG020/FC-GB(ECD)/ALDR-2K/MAY12 Enquiries relating to this publication should be addressed to: Forestry Commission Silvan House 231 Corstorphine Road Edinburgh EH12 7AT 0131 334 0303 [email protected] In Northern Ireland, to: Forest Service Department of Agriculture and Rural Development Dundonald House Upper Newtownards Road Ballymiscaw Belfast BT4 3SB 02890 524480 [email protected] The Forestry Commission will consider all requests to make the content of publications available in alternative formats. Please direct requests to the Forestry Commission Diversity Team at the above address, or by email at [email protected] or by phone on 0131 314 6575. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the following contributors: Fred Currie (retired Forestry Commission England); Jill Butler (Woodland Trust); Keith Kirby (Natural England); Iain MacGowan (Scottish Natural Heritage). -

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review Interim HRA to support the plan making process November 2019 Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Worcestershire Development Plan Review Interim HRA to support the plan making process Preferred Options LC-578 Document Control Box Client Malvern Hills District Council Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Worcestershire Development Report Title Plan: Preferred Options Status Final Interim HRA Filename LC-578_SWDPR_HRA_Screening Report_11_141119SC.docx Date November 2019 Author LB Reviewed SC Approved ND Photo: Bredon Hill by Lepus Consulting South Worcestershire Interim HRA Report to support the plan making process November 2019 LC-578_SWDPR_HRA_Screening Report_11_141119SC.docx Contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The HRA process ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 2 SWDPR ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1 South Worcestershire Development Plan Review ....................................................................................... 5 2.2 Background to the Local Plan Development ................................................................................................ -

FOLIA ENTOMOLOGICA HUNGARICA ROVARTANI KÖZLEMÉNYEK Volume 66 2005 Pp

FOLIA ENTOMOLOGICA HUNGARICA ROVARTANI KÖZLEMÉNYEK Volume 66 2005 pp. 63–80. Distributional notes and a checklist of click beetles (Coleoptera: Elateridae) from Hungary O. MERKL1* & J. MERTLIK2 1Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-1088 Budapest, Baross u. 13, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 2Na kotli 1174, CZ-500 09 Hradec Králové, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract – First records of Ampedus hjorti (RYE, 1905), Ampedus quercicola (BUYSSON, 1887), Athous apfelbecki REITTER, 1905, Athous zebei BACH, 1854, Brachygonus ruficeps (MULSANT et GUILLEBEAU, 1855), Cidnopus platiai MERTLIK, 1996, Cidnopus ruzenae (LAIBNER, 1977), Ectinus aterrimus (LINNAEUS, 1761), Limoniscus violaceus (P. W. J. MÜLLER, 1821), Megapenthes lugens (REDTENBACHER, 1842), Oedostethus quadripustulatus (FABRICIUS, 1792), Reitterelater bouyoni (CHASSAIN, 1992), Reitterelater dubius PLATIA et CATE, 1990, Zorochros flavipes (AUBÉ, 1850), Zorochros meridionalis (LAPORTE DE CASTELNAU, 1840) and Zorochros stibicki LESEIGNEUR, 1970 for the fauna of Hungary are given. Twelve species are deleted from the Hungarian faunal list. A checklist of the Elateridae of Hungary (131 species) is presented. Key words – Coleoptera, Elateridae, checklist, Hungary. INTRODUCTION Since KUTHY’s (1897) volume on Coleoptera in the Fauna Regni Hungariae no complete list of the Elateridae of Hungary has been published. KUTHY men- tioned 148 species (including Drapetes cinctus (PANZER, 1796) in the family Euc- nemidae) known to occur in Hungary, but many of his records refer to former Hun- garian regions now belonging to Slovakia, the Ukraine, Romania, Serbia and Croatia. A number of species listed by him are not expected to occur in present-day Hungary, either because they belong to the fauna of the higher regions of the Carpathian Mountains or because they are species with a more southern distribu- * Corresponding author. -

Home Is Where the Heart Rot Is: Violet Click Beetle, Limoniscus Violaceus (Müller, 1821), Habitat Attributes and Volatiles

Insect Conservation and Diversity (2020) doi: 10.1111/icad.12441 SHORT COMMUNICATION Home is where the heart rot is: violet click beetle, Limoniscus violaceus (Müller, 1821), habitat attributes and volatiles JORDAN PATRICK CUFF, CARSTEN THEODOR MÜLLER, EMMA CHRISTINE GILMARTIN, LYNNE BODDY and THOMAS HEFIN JONES School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK Abstract. 1. The decreasing number of veteran trees in Europe threatens old-growth habitats and the fauna they support. This includes rare taxa, such as the violet click beetle, Limoniscus violaceus (Müller, 1821). 2. Samples of wood mould were taken from all beech trees in Windsor Forest previ- ously confirmed to have contained L. violaceus larvae, and from trees where L. violaceus had not previously been detected, the latter categorised as having high, medium or low likelihood of containing the beetle during recent surveys. Habitat characteristics were measured, and volatile profiles determined using gas-chromatography mass- spectrometry. 3. Water content significantly differed between tree hollows of different violet click beetle status, high-potential habitats having higher and relatively stable water content compared with habitats with medium or low potential of beetle occupancy. Several vol- atile organic compounds (VOCs) were significantly associated with L. violaceus habitats. No differences in other characteristics were detected. 4. The distinction in water regime between habitats highlights that recording this quantitatively could improve habitat surveys. Several potential L. violaceus attractant VOCs were identified. These could potentially be integrated into existing monitoring strategies, such as through volatile-baited emergence traps or volatile-based surveying of habitats, for more efficient population monitoring of the beetle. Key words. -

Nemethkovacs Et Al.Indd

FOLIA ENTOMOLOGICA HUNGARICA ROVARTANI KÖZLEMÉNYEK Volume 78 2017 pp. 57–70 Updated knowledge on the records for the endangered click beetle Limoniscus violaceus in Hungary (Coleoptera: Elateridae) Tamás Németh1*, Tibor Kovács2, Csaba Kutasi3, Andor Lőkkös4, György Rozner4 & Valentin Szénási5 1Hungarian Natural History Museum, Department of Zoology, H-1088 Budapest, Baross utca 13, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 2Mátra Museum of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-3200 Gyöngyös, Kossuth Lajos út 40. Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 3Bakony Museum of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-8420 Zirc, Rákóczi tér 3–5, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] 4Balaton-felvidéki National Park Directorate, H-8229 Csopak, Kossuth Lajos utca 13, Hungary. E-mails: [email protected], [email protected] 5Duna–Ipoly National Park Directorate, H-1021 Budapest, Költő utca 21, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract – Faunistic data for the violet click beetle, Limoniscus violaceus (P. W. J. Müller, 1821), from Hungary and notes on its life history are given. With 7 fi gures. Key words – faunistic records, life history, Natura 2000 species, saproxylic INTRODUCTION Th e violet click beetle, Limoniscus violaceus (P. W. J. Müller, 1821), a sapro- xyl ic elaterid species, occurs in several European countries (Cate 2007) and in Turkey (Mertlik & Dusanek 2006, Růžička et al. 2006). It is listed in the Annex II of the Habitats Directive (Council of the European Union 1992) and as a species of community interest (Natura 2000 species). Th e fi rst capture of the violet click beetle in Hungary is from the early 1990s (Merkl & Mertlik 2005), based on a specimen without more exact date record. -

NECR252 Edition 1 Development of DNA Applications in Natural

Natural England Commissioned Report NECR252 Development of DNA applications in Natural England 2016/2017 First published August 2018 www.gov.uk/natural-england Foreword Natural England commission a range of reports from external contractors to provide evidence and advice to assist us in delivering our duties. The views in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Natural England. Background DNA based applications have the potential to There are still significant limitations to the use of significantly change how we monitor this technology in others areas and in 2016/17 biodiversity and which species and taxa we Natural England worked with NatureMetrics on a monitor. These techniques may provide number of exploratory projects looking at species cheaper alternatives to existing species detection in standing freshwaters, saline lagoons, monitoring, an ability to detect species that we coastal waters and sediments, terrestrial do not currently monitor effectively and the invertebrate traps, deadwood mould, vegetation potential to develop new measures of habitat and soils. This report presents the results from and ecosystem quality. those projects. Natural England has been supporting the This report should be cited as: development of DNA techniques for a number TANG, C.Q., CRAMPTON-PLATT, A., of years. The use of environmental DNA TOWNEND, S., BRUCE, K., BISTA, I. & CREER, (eDNA) to determine the presence or absence S. 2018. Development of DNA applications in of great crested newts in ponds is now a Natural -

Planning for the Protection of European Sites: Habitat Regulations Assessment (HRA) / Appropriate Assessment (AA)

Planning for the Protection of European Sites: Habitat Regulations Assessment (HRA) / Appropriate Assessment (AA) Evidence Gathering / Baseline Report (Update 1) (May 2009) Gloucestershire Minerals & Waste Development Framework 1 Contents Page Section 1: Introduction 3 International / European Sites – An Introduction 3 An Updated Report 3 Background to Evidence Gathering for HRA 4 Updated List of Consultees 5 Other Plans and Projects 6 HRA Reports: Methodology 7 Section 2: European sites in Gloucestershire and within 15km of its administrative boundary 9 Rodborough Common 9 Dixton Wood 11 Wye Valley and Forest of Dean Bat Sites 13 River Wye 16 Wye Valley Woodlands 19 North Meadow and Clattinger Farm 22 Cotswold Beechwoods 24 Bredon Hill 27 Walmore Common 29 Severn Estuary 31 Avon Gorge Woodlands 37 Section 3: Conclusion and Contact Details 39 Appendix 1: Original Evidence Gathering / Baseline Report: List of Consultees and Responses 40 Appendix 2: Indicative Locations of Waste Management Facilities in Gloucestershire 44 Appendix 3: The Spatial Distribution of Active Mineral Sites in Gloucestershire 45 1 European sites in and within 15km of Gloucestershire’s boundary 2 Section 1: Introduction International / European Sites - An Introduction The EU Natura 2000 network provides ecological infrastructure for the protection of sites which are of exceptional importance in respect of rare, endangered or vulnerable natural habitats and species within the European Union. These sites, which are also referred to as „European sites‟ consist of Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and Offshore Marine Sites (OMS). Note: there are no OMS designated at present. Ramsar sites (Internationally Important Wetlands) are treated as it they were European sites in accordance with the Government‟s policy statement of November 2000 and the DEFRA Circular 01/2005 (paragraph 5). -

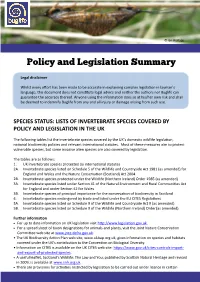

Policy and Legislation Summary

© Ian Wallace Policy and Legislation Summary Legal disclaimer Whilst every effort has been made to be accurate in explaining complex legislation in layman’s language, this document does not constitute legal advice and neither the authors nor Buglife can guarantee the accuracy thereof. Anyone using the information does so at his/her own risk and shall be deemed to indemnify Buglife from any and all injury or damage arising from such use. SPECIES STATUS: LISTS OF INVERTEBRATE SPECIES COVERED BY POLICY AND LEGISLATION IN THE UK The following tables list the invertebrate species covered by the UK’s domestic wildlife legislation, national biodiversity policies and relevant international statutes. Most of these measures aim to protect vulnerable species, but some invasive alien species are also covered by legislation. The tables are as follows: 1. UK invertebrate species protected by international statutes 2A. Invertebrate species listed on Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended) for England and Wales and the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. 2B. Invertebrate species protected under the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 (as amended) 3A. Invertebrate species listed under Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities Act for England and under Section 42 for Wales 3B. Invertebrate species of principal importance for the conservation of biodiversity in Scotland 4. Invertebrate species endangered by trade and listed under the EU CITES Regulations 5A. Invertebrate species listed on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 9 (as amended) 5B. Invertebrate species listed on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order (as amended) Further information For up to date information on UK legislation visit http://www.legislation.gov.uk. -

Worcestershire County Council Minerals Local Plan Habitats

Worcestershire County Council Minerals Local Plan Habitats Regulation Assessment Publication Version Record of Assessment 1.3 February 2020 Contents 1. Executive Summary.............................................................................. 6 2. Introduction........................................................................................... 8 Background to HRA ............................................................................. 8 Legislation ............................................................................................ 8 Guidance and Process ......................................................................... 9 Habitats Regulations Assessment Process ........................................ 10 Approach to dealing with uncertainty ................................................. 10 Regulatory and Implementation Uncertainty: ..................................... 11 Planning Hierarchy Uncertainty: ......................................................... 11 3. Scanning and site selection list ........................................................... 12 Information for Assessment ............................................................... 17 4. Key Potential Impacts ......................................................................... 28 5. Approach to the Application of a Screening Framework ..................... 36 Interpretation of ‘likely significant effect’ ............................................. 36 Consideration of Site Scanning Results: ...........................................