AAWE Working Paper No. 159 – Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3

Book Reviews 423 JASON WISE (Director): SOMM 3. Written by Christina Wise and Jason Wise, Produced by Forgotten Man Films, Distributed by Samuel Goldwyn Films, 2018; 1 h 18 min. This is the third in a trilogy of documentaries about the wine world from Jason Wise. The first—Somm, a marvelous film which I reviewed for this Journal in 2013 (Stavins, 2013)–followed a group of four thirty-something sommeliers as they prepared for the exam that would permit them to join the Court of Master Sommeliers, the pinnacle of the profession, a level achieved by only 200 people glob- ally over half a century. The second in the series—Somm: Into the Bottle—provided an exploration of the many elements that go into producing a bottle of wine. And the third—Somm 3—unites its predecessors by combining information and evocative scenes with a genuine dramatic arc, which may not have you on pins and needles as the first film did, but nevertheless provides what is needed to create a film that should not be missed by oenophiles, and many others for that matter. Before going further, I must take note of some unfortunate, even tragic events that have recently involved the segment of the wine industry—sommeliers—featured in this and the previous films in the series. Five years after the original Somm was released, a cheating scandal rocked the Court of Master Sommeliers, when the results of the tasting portion of the 2018 exam were invalidated because a proctor had disclosed confidential test information the day of the exam. -

Dolemite Is My Name

DOLEMITE IS MY NAME Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski FINAL IN THE BLACK We hear Marvin Gaye's "What's Goin' On" playing softly. VOICE I ain't lying. People love me. INT. DOLPHIN'S - DAY CU of a beat-up record from the 1950s. On the paper cover is a VERY YOUNG Rudy, in a tuxedo. It says "Rudy Moore - BUGGY RIDE" RUDY You play this, folks gonna start hoppin' and squirmin', just like back in the day. A hand lifts the record up to the face of RUDY RAY MOORE, late '40s, black, sweet, determined. RUDY When I sang this on stage, I swear to God, people fainted! Ambulance man was picking them off the floor! When I had a gig, the promoter would warn the hospital: "Rudy's on tonight -- you're gonna be carrying bodies out of the motherfucking club!" We see that we are in a RADIO BOOTH. A sign blinks "On The Air." The DJ, ROJ, frowns at the record. ROJ "Buggy Ride"? RUDY Wasn't no small-time shit. ROJ GodDAMN, Rudy! That record's 1000 years old! I've got Marvin Gaye singin' "Let's Get It On"! I can't be playin' no "Buggy Ride." (beat) Look, I have 60 seconds. I have to cue the next tune. Hm! Rudy bites his lip and walks away. Roj tries to go back to his job. He reaches for a Sly Stone single -- when Rudy suddenly bounds back up. RUDY How about "Step It Up and Go"? That's a real catchy rhythm-and-blues number. -

Un Retrato De La Actriz: Pam Grier

Un retrato de la actriz: Pam Grier Escrito por Kymberly Keeton Viernes 21 de Diciembre de 2012 12:24 La actriz Pam Grier, mejor conocida por sus papeles en películas del género blaxploitation en los años 70, regresa con una nota sobre avance, feminismo, vida, amor, sexualidad e independencia. Estos mensajes son escritos en una lengua vernácula fácil para sus fans. Su autobiografía, My Life in Three Acts: Foxy, echa una mirada fascinante a la vida y legado de Grier. Durante el verano de 2010 hizo una gira por los Estados Unidos presentando el libro. Para Grier, fue “la gira del gran abrazo consolador”. La actriz Afroamericana nació en Winston-Salem, Carolina del Norte. La madre de Pam Grier era enfermera, y su padre era sargento técnico de la fuerza aérea de Estados Unidos. Tiene una hermana y un hermano. Como resultado de vivir en una familia militar, los Grier se mudan a menudo. El libro inicia con Pam Grier hablando sobre su descubrimiento de que los Afroamericanos y los Blancos no se comunicaban entre sí en los años sesenta. 1 / 5 Un retrato de la actriz: Pam Grier Escrito por Kymberly Keeton Viernes 21 de Diciembre de 2012 12:24 La actriz habla abiertamente sobre el racismo en los Estados Unidos mientras crecía en Denver, Colorado. “Te das cuenta que era una opresión {durante esos tiempos} … me daba cuenta de cómo los padres ocultaban su ira para salvar a sus familias. También podías ver que personas de otra raza te veían diferente. En aquel entonces, los padres te decían por qué otras gente tenía prejuicios sobre ti”. -

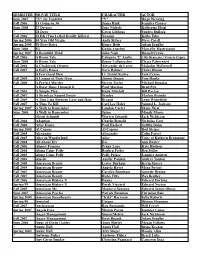

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Radio Guest List

iWineRadio℗ Wine-Centric Connection since 1999 Wine, Food, Travel, Business Talk Hosted and Produced by Lynn Krielow Chamberlain, oral historian iWineRadio is the first internet radio broadcast dedicated to wine iWineRadio—Guest Links Listen to iWineRadio on iTunes Internet Radio News/Talk FaceBook @iWineRadio on Twitter iWineRadio on TuneIn Contact Via Email View My Profile on LinkedIn Guest List Updated February 20, 2017 © 1999 - 2017 lynn krielow chamberlain Amy Reiley, Master of Gastronomy, Author, Fork Me, Spoon Me & Romancing the Stove, on the Aphrodisiac Food & Wine Pairing Class at Dutton-Goldfield Winery, Sebastopol. iWineRadio 1088 Nancy Light, Wine Institute, September is California Wine Month & 2015 Market Study. iWineRadio1087 David Bova, General Manager and Vice President, Millbrook Vineyards & Winery, Hudson River Region, New York. iWineRadio1086 Jeff Mangahas, Winemaker, Williams Selyem, Healdsburg. iWineRadio1085a John Terlato, “Exploring Burgundy” for Clever Root Summer 2016. iWineRadio1085b John Dyson, Proprietor: Williams Selyem Winery, Millbrook Vineyards and Winery, and Villa Pillo. iWineRadio1084 Ernst Loosen, Celebrated Riesling Producer from the Mosel Valley and Pfalz with Dr. Loosen Estate, Dr. L. Family of Rieslings, and Villa Wolf. iWineRadio1083 Goldeneye Winery's Inaugural Anderson Valley 2012 Brut Rose Sparkling Wine, Michael Fay, Winemaker. iWineRadio1082a Douglas Stewart Lichen Estate Grower-Produced Sparkling Wines, Anderson Valley. iWineRadio1082b Signal Ridge 2012 Anderson Valley Brut Sparkling Wine, Stephanie Rivin. iWineRadio1082c Schulze Vineyards & Winery, Buffalo, NY, Niagara Falls Wine Trail; Ann Schulze. iWineRadio1082d Ruche di Castagnole Monferrato Red Wine of Piemonte, Italy, reporting, Becky Sue Epstein. iWineRadio1082e Hugh Davies on Schramsberg Brut Anderson Valley 2010 and Schramsberg Reserve 2007. iWineRadio1082f Kristy Charles, Co-Founder, Foursight Wines, 4th generation Anderson Valley. -

She's a Whole Lotta Woman. Pam Grier

Lataya Lattany 6th Period April 24, 2017 She’s A Whole Lotta Woman. Pam Grier “I do a movie once every four years and they call it a comeback.” Synopsis Pamela Suzette Grier is an American actress. She was born on May 26, 1949 and she is currently 67 years old. She is known for being in movies such as The Big Bird Cage, Coffy, Foxy Brown, and Sheba Baby. Early Life Pam was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Her mom was a nurse and her dad was an Air Force mechanic. She also had three siblings. Due to her father being in the military, she moved around a lot. She eventually settled in Denver and went to East High School. She participated in stage productions and she entered beauty contests to earn money for college. After she graduated from high school, she went to Metropolitan State College. Movies In 1970, Pam was a character in Beyond the Valley of the Dolls after moving to Los Angeles to go to film school and being discovered by Jack Hill. This marked the start of her acting career. Over time, Pam starred in movies such as Jackie Brown, The Big Doll House, and Above the Law. She also was in movies such as Ghost in Mars and Bones in the early 2000s. Because of her roles in movies, she was nominated for and won many awards. She was mainly in blaxploitation movies which geared towards black audiences and showcased their stereotypes. Pam’s Global Impact Millions of people have watched Pam Grier movies. -

The Problem of Female Antagonisms in Blaxploitation Cinema Melissa

1 Who’s Got the “Reel” Power? The Problem of Female Antagonisms in Blaxploitation Cinema Melissa DeAnn Seifert, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Abstract: Between 1973 and 1975, films starring Pam Grier and Tamara Dobson such as Cleopatra Jones (Jack Starrett, 1973), Coffy (Jack Hill, 1973) and Foxy Brown (Hill, 1974) introduced leading black women into the predominantly male blaxploitation scene as aggressive action heroines. Within the cinematic spaces of blaxploitation films which featured women as active agents, a racial and sexual divide exists. These films positioned women either inside or outside of gender tolerability by utilising binary constructions of identity based on race, sex and elementary constructions of good and evil, black and white, straight and gay, and feminine and butch. Popular representations of lesbianism and sisterhood within blaxploitation cinema reflect a dominant social view of American lesbianism as white while straight women are consistently represented as black. However, these spaces also constricted black and white female identities by limiting sexuality and morality to racial boundaries. This article seeks to question the unique solitude of these female heroines and interrogate a patriarchal cinematic world where sisterhood is often prohibited and lesbianism demonised. I don’t believe in [women’s lib] for black people … we’re trying to free our black men … I like being a woman. I have been discriminated against, but not because I’m a woman. It’s because I am black … before [people] see me as being female, they see me as being black. The stigma that’s been placed on you because you’re black gives you enough kill to get you through the woman thing … it’s much tougher being black than being a woman. -

A Queer and Gendered Analysis of Blaxploitation Films

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Social and Cultural Sciences Faculty Research and Publications/Department of Social and Cultural Sciences This paper is NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; but the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation below. Western Journal of Black Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (2013): 28-38. DOI. This article is © Washington State University and permission has been granted for this version to appear in e- Publications@Marquette. Washington State University does not grant permission for this article to be further copied/distributed or hosted elsewhere without the express permission from Washington State University. Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Literature Review .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Social Identity Theory ............................................................................................................................... 3 The Politics of Semiotics ........................................................................................................................... 4 Creating Racial Identity through Film and -

Proquest Dissertations

Love and Cinema- Cinephilia, Style, and the Films of Quentin Tarantino by Matthew Harris A (thesis) submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario Tuesday, January 4 2011, Matthew Harris Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-79566-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-79566-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Movie Suggestions for 55 and Older: #4 (141) After the Ball

Movie Suggestions for 55 and older: #4 (141) After The Ball - Comedy - Female fashion designer who has strikes against her because father sells knockoffs, gives up and tries to work her way up in the family business with legitimate designes of her own. Lots of obstacles from stepmother’s daughters. {The} Alamo - Western - John Wayne, Richard Widmark, Laurence Harvey, Richard Boone, Frankie Avalon, Patrick Wayne, Linda Cristal, Joan O’Brien, Chill Wills, Ken Curtis, Carlos Arru , Jester Hairston, Joseph Calleia. 185 men stood against 7,000 at the Alamo. It was filmed close to the site of the actual battle. Alive - Adventure - Ethan Hawke, Vincent Spano, James Newton Howard, et al. Based on a true story. Rugby players live through a plane crash in the Andes Mountains. When they realize the rescue isn’t coming, they figure ways to stay alive. Overcoming huge odds against their survival, this is about courage in the face of desolation, other disasters, and the limits of human courage and endurance. Rated “R”. {The} American Friend - Suspense - Dennis Hopper, Bruno Ganz, Lisa Kreuzer, Gerard Blain, Nicholas Ray, Samuel Fuller, Peter Lilienthal, Daniel Schmid, Jean Eustache, Sandy Whitelaw, Lou Castel. An American sociopath art dealer (forged paintings) sells in Germany. He meets an idealistic art restorer who is dying. The two work together so the German man’s family can get funds. This is considered a worldwide cult film. Amongst White Clouds - 294.3 AMO - Buddhist, Hermit Masters of China’s Zhongnan Mountains. Winner of many awards. “An unforgettable journey into the hidden tradition of China’s Buddhist hermit monks. -

Wine Waves Further Following the Grape from Vineyards to Ship to Glass

Wine Waves Further Following The Grape From Vineyards To Ship To Glass By Cele & Lynn Seldon hen it's time to toast with a glass of W wine at sea, your vintage of choice has likely logged many miles before it was poured for your pleasure. How wine makes its way to ships and into glasses, and the widely varied ways it's enjoyed at sea and in ports during a cruise vacation, makes for two toast-worthy tales for anyone who en joys the fruit of the vine. The first installment of this tasty series (Cruise Travel, March/April 2016) high lighted how Oceania Cruises and Carnival Cruise Line get wine to their ships, on their wine lists, and into guest glasses. This part further explores wine at sea-and ashore. Of course, before wine is produced, bot tled, and shipped, grapes have to be grown and picked. This occurs around the world year-round and in every hemisphere, includ ing classic Old World grape-growing and More than 200 certified sommeliers guide guest choices on Celebrity Cruises; on Solstice-Class vessels, main-dining-room selections are made from the dramatic two-story-tall wine "towers." 38 Cruise Travel May/June 2016 wine-producing regions in France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, and beyond, as well as numerous New World winemaking wonders in the United States, Argentina, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and more. Once it's produced and bottled, wine makes its way to ships in various ways. Typically, however, cruise lines work with distributors and other specialized companies and services to purchase, store, and deliver wine to ships when they are in ports for restocking. -

Marie Larkin Hair Stylist IATSE 706

Marie Larkin Hair Stylist IATSE 706 FILM UNTITLED TODD HAYNES PROJECT Department Head Lionsgate Director: Todd Haynes Cast: Mark Ruffalo, Bill Camp, Bill Pullman, Mare Winningham THE LAUNDROMAT Department Head Netflix Director: Steven Soderbergh Cast: Antonio Banderas, Gary Oldman, Jeffrey Wright, Rosalind Chao TRIPLE FRONTIER Department Head Netflix Director: J.C. Chandor Cast: Oscar Isaac, Charlie Hunnam, Garrett Hedlund FIRST MAN Department Head Paramount Director: Damien Chazelle Cast: Claire Foy, Jason Clarke, Kyle Chandler, Ciarán Hinds, Olivia Hamilton LOGAN LUCKY Department Head Trans-Radial Pictures Director: Steven Soderbergh Cast: Channing Tatum, Adam Driver, Daniel Craig, Seth McFarlane, Katie Holmes, Riley Keough, Bryan Gleason, Jack Quaid MOSAIC Department Head HBO Director: Steven Soderbergh Cast: Garrett Hedlund, Jennifer Ferrin, Paul Ruebens, Jeremy Bobb AMERICAN MADE Department Head Imagine Entertainment Director: Doug Liman Cast: Domhnall Gleeson, Sarah Wright, Caleb Landry Jones, Jayma Mays, Lola Kirke THE JUNGLE BOOK Department Head Walt Disney Pictures Director: Jon Favreau Cast: Neel Sethi CHEF Department Head Open Road Films Director: Jon Favreau Cast: Jon Favreau, John Leguizamo THE MILTON AGENCY Marie Larkin 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hairstylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 3 BEHIND THE CANDELABRA Department Head HBO Films Director: Steven Soderbergh Cast: Scott Bakula, Debbie Reynolds, Dan Akroyd, Rob Lowe, Cheyenne Jackson Winner: 2013 Emmy Award for Outstanding Hairstyling For A Miniseries Or A Movie Nominee: 2014 BAFTA Award for Best Make-Up and Hair Winner: Make-Up Artist & Hair Stylist Guild Awards – Best Period and/or Character Hair Styling – Television Mini-Series or M.O.W.