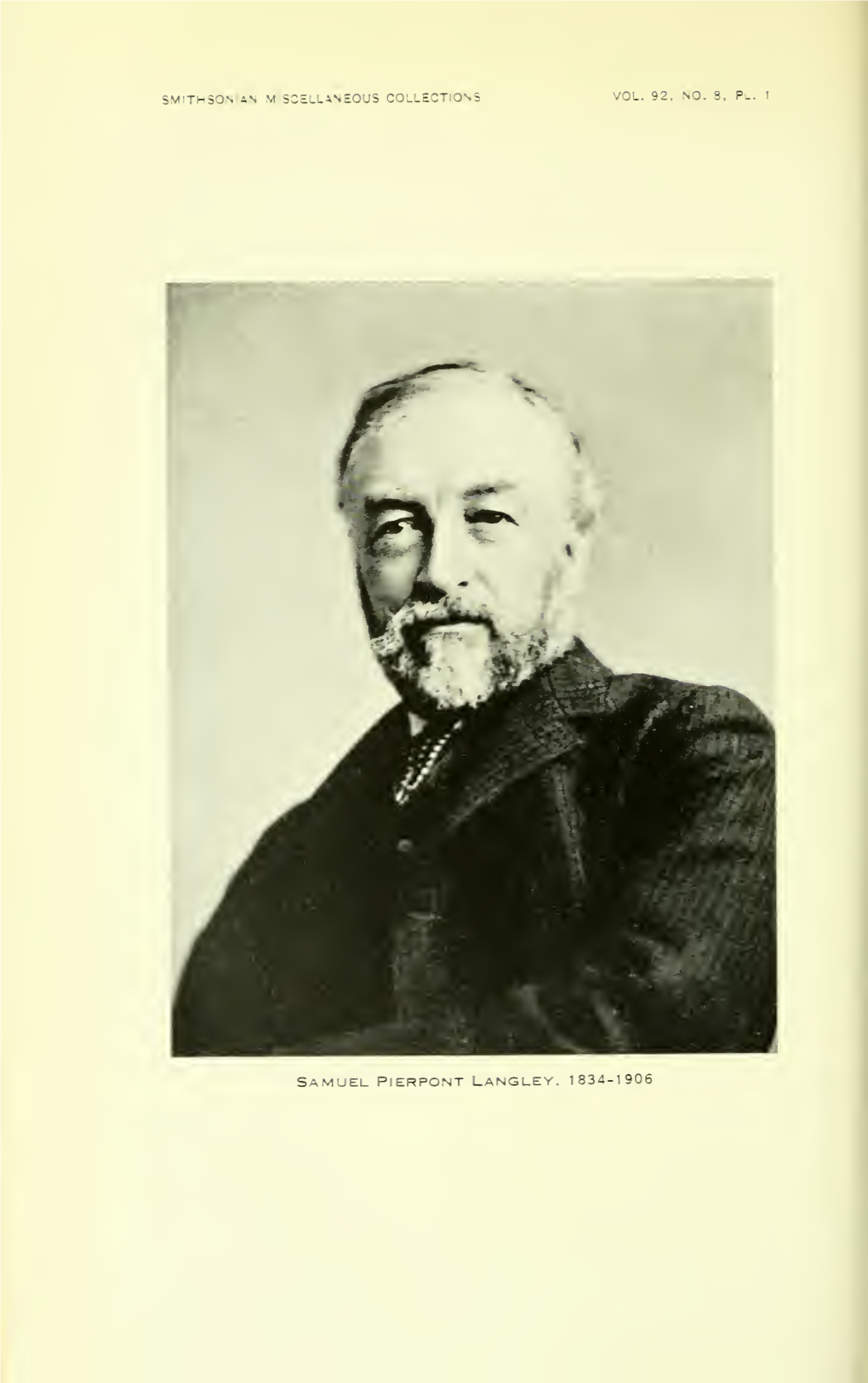

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

January 2010 Malama

SIERRA CLUB Cherish the Earth JOURNAL OF THE SIERRA CLUB, HAWAI`I CHAPTER A Quarterly Newsletter January - March 2010 Planting Native! Bold Policy Proposals Hey Mr. Green! Nate’s Adventures! National Ocean Policy Task Force Guest Entering the new year, Looking for ways to columnist what bold and realistic save the environment? Long-time Sierra Club Rick policy proposals can we Check out our advice volunteer Dave Raney Barbosa promote in order to column on short, easy describes the mission of SAVE A TREE! writes ensure a greener tips that you can use to the National Ocean about the Hawai`i? Learn about help save the Policy Task and some Receive your Malama the issues the Sierra Club environment. This Join Nate Yuen as he of the current electronically by going distribution, care, and is advocating month suggests how to describes a recent hike recommendations to cultural use of the native be green and save some along Wailuku River. being proposed. www.hi.sierraclub.org Ho`awa. Page 5 green! Click the link below Pages 8 - 9 Pages 10 - 11 “Email My Newsletter” Page 3 Page 6 private homes. Sandy areas -- where children build sand castles and Preserving sunbathers get “tan” -- are increasingly scarce and usually quite crowded. Sandy Hawai`i coastlines are dynamic. Beaches erode or accrete depending upon their location on the coast, their Beaches proximity to various things such as piers, sandwalls, the impact of storms, etc. Anyone who buys beachfront A Proposal to Protect Hawai’i’s property is made aware of the fact that Beaches for Our Keiki boundaries between private property and the public easement may shift over by Robert D. -

Lowellobserver

THE ISSUE 105 FALL 2015 LOWELL OBSERVER THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF LOWELL OBSERVATORY HOME OF PLUTO Just 15 minutes after its closest approach to Pluto on July 14, 2015, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft looked back toward the Sun and captured a near- sunset view of the rugged, icy mountains and flat ice plains extending to Pluto’s horizon. (NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI) IN THIS SPECIAL EXTENDED ISSUE 2 Director’s Update 2 Trustee’s Update 3 Bound for Chile! New Horizons Unveils Pluto’s Secrets By Will Grundy Astronomers can normally study memes. Importantly, the focus remained distant objects only through their light, so almost entirely on the science, not hare- a unique appeal of solar system science is brained conspiracy theories or umbrage the possibility to send spacecraft to study at off-the-cuff remarks of team members. bodies in ways that could only be done Pluto, the real star of the show, up-close. Such spacecraft exploration isn’t certainly rose to the occasion, revealing 4 Education On Board SOFIA cheap, and competition is fierce over which incredible complexities and stark beauty. missions should be flown. The opportunity But much about the encounter was 5 Pluto Occultation Team to participate in one is a rare and cherished attributable to the hard-working team 6 Lowell Hosts Pluto Palooza opportunity for a planetary scientist like who delivered Pluto to the world. How myself. That’s especially so for a first-ever was this done, and what was it like being encounter with a previously unexplored involved? The key was practice. -

100 Years and Never Felt Better! Preface

A Centennial History of the Victoria Centre The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada 100 YEARS AND NEVER FELT BETTER! PREFACE OME YEARS AGO a fortuitous rummage been reproduced in this book. Nevertheless, an through the Victoria Centre’s library re- inclusive historical record has finally emerged. Svealed that an earlier attempt had been Also, it stands to reason that the last 20 or so made to start a Centre in Victoria in 1907. years have been given greater prominence in this We were completely unaware of this unex- history due to the availability of richer and more pected event, buried as it was, and when we next diversified material. discovered that we were unknowingly on the In a record of this nature it has not been pos- verge of celebrating our centenary in 2014 it sible to delve into the history of every prominent added to the surprise. member or officer, or cover every minor event Someone had to do a ton of digging into our pursued by the Centre history. That someone turned out to be me! However, an effort has been made to mention Soon, our ever-helpful librarian, Sid Sidhu, members who have contributed something of presented me with piles of musty, decades old value to the Centre’s membership. flotsam that had accumulated in the bowels of PRINTED COPIES AND CD’S his library cupboards. It was decided to produce a few printed copies Boxes of papers mixed with stacks of ancient on acid-free paper and burn some CD’s for ar- RASC Journals, the Centre’s monthly Skynews chival and longevity reasons. -

Griffith Observer Cumulative Index

Griffith Observer Cumulative Index author title mo year key words Anonymous The Romance of the Calendar 2 1937 calendar, Julian, Gregorian Anonymous Other Worlds than Ours 3 1937 Planets, Solar System Anonymous The S ola r Fa mily 3 1937 Planets, Solar System Roya l Elliott Behind the Sciences 3 1937 GO, pla ne ta rium, e xhibits , Ge ologica l Clock Anonymous The Stars of Spring 4 1937 Cons te lla tions , S ta rs , Anonymous Pronunciation of Star and 4 1937 Cons te lla tions , S ta rs Constellation Names Anonymous The Cycle of the Seasons 5 1937 Seasons, climate Anonymous The Ice Ages 5 1937 United States, Climate, Greenhouse Gases, Volcano, Ice Age Anonymous New Meteorites at the Griffith 5 1937 Meteorites Observatory Anonymous Conditions of Eclipse 6 1937 Solar eclipse, June 8, Occurrences 1937, Umbra, Sun, Moon Anonymous Ancient and Modern Eclipse 6 1937 Chinese, Observation, Observations Eclips e , Re la tivity Anonymous The Sky as Seen from 6 1937 Stars, Celestial Sphere, Different Latitudes Equator, Pole, Latitude Anonymous Laws of Polar Motion 6 1937 Pole, Equator, Latitude Anonymous The Polar Aurora 7 1937 Northern lights, Aurora Anonymous The Astrorama 7 1937 Star map, Planisphere, Astrorama Anonymous The Life Story of the Moon 8 1937 Moon, Earth's rotation, Darwin Anonymous Conditions on the Moon 8 1937 Moon, Temperature, Anonymous The New Comet 8 1937 Come t Fins le r Anonymous Comets 9 1937 Halley's Comet, Meteor Anonymous Meteors 9 1937 Meteor Crater, Shower, Leonids Anonymous Comet Orbits 9 1937 Comets, Encke Anonymous -

Your Story Is Our Story

H A F YOUR STORY IS OUR STORY 2014 | 2015 OUR STRATEGIC GOALS To promote and encourage generosity, leadership, and inclusion to strengthen our communities, HAF has developed five strategic goals to accomplish by 2020. We’re committed to: • Transforming Our Communities’ Abilities to Solve Problems and Address Root Causes – We are cultivating skilled leaders and supporting community initiatives that create long-term solutions. We support healing and improving health outcomes in Native communities and beyond. • Strengthening Community Capacity – We prioritize grants that respond to immediate and long-term community needs. We work to strengthen our nonprofit partners, to increase access to post-secondary education, and to serve as a catalyst and connector for economic development. • Building and Leveraging Funds and Partnerships – We are expanding our offerings to better support the objectives of donors and to educate our community on the long term impacts of giving. We partner with other funders and supporting organizations to increase our impact. • Strengthening Internal Infrastructure – We are continuously improving our operations to best serve our community. We are dedicated to teamwork, transparency and best practices. • Sustainable Strategy and Accountability – We model professional excellence in everything we do. We listen, engage, and respond with cultural awareness and evaluate our impact to better serve our communities. Contents Letter from the 2 Executive Director Who We Are and What 4 We Do 6 Because of You 8 How To Help 112 Grants -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Astrophysics in 2001 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2353n2st Journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 114(795) ISSN 0004-6280 Authors Trimble, V Aschwanden, MJ Publication Date 2002-12-01 DOI 10.1086/341673 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 114:475–528, 2002 May ᭧ 2002. The Astronomical Society of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. Invited Review Astrophysics in 2001 Virginia Trimble Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697; and Astronomy Department, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742; [email protected] and Markus J. Aschwanden Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, Department L9-41, Building 252, 3251 Hanover Street, Palo Alto, CA 94304; [email protected] Received 2002 January 24; accepted 2002 January 25 ABSTRACT. During the year, astronomers provided explanations for solar topics ranging from the multiple personality disorder of neutrinos to cannibalism of CMEs (coronal mass ejections) and extra-solar topics including quivering stars, out-of-phase gaseous media, black holes of all sizes (too large, too small, and too medium), and the existence of the universe. Some of these explanations are probably possibly true, though the authors are not betting large sums on any one. The data ought to remain true forever, though this requires a careful definition of “data” (think of the Martian canals). 1. -

Lunar and Planetary Information Bulletin

Issue #154 HAYABUSA2: Bringing Home a Mystery Featured Story · News from Space · The Lunar and Planetary Institute’s 50th Anniversary Science Symposium · Meeting Highlights · Opportunities for Students · Spotlight on Education · In Memoriam · Milestones · New and Noteworthy · Calendar LUNAR AND PLANETARY INFORMATION BULLETIN October 2018 Issue 154 Issue #154 2 of 53 October 2018 Featured Story Hayabusa2: Bringing Home a Mystery On May 9, 2003, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched Hayabusa, the first mission to return an asteroid sample back to Earth. Fifteen years later, JAXA, in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), has sent a second mission to rendezvous with an asteroid, with the objective of returning yet another sample. Both Hayabusa missions were designed to provide insight and understanding into the building blocks of the solar system. Hayabusa brought us back pieces of 25143 Itokawa, an S-class asteroid. Hayabusa2 is on course to return samples from 162173 Ryugu, a C-class asteroid. This sample will be the first returned from a C-class asteroid. The Spacecraft Hayabusa2 launched on December 3, 2014, and arrived at its target, Ryugu, on June 27, 2018. This bold, exciting mission has raised the bar on its predecessor by including a lander (the Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout, MASCOT, a collaboration with ESA) and three MINERVA_II rovers, as well as targeting three touchdowns to sample the surface. The sampling payload also includes the Small Carry-on Impactor (SCI), designed to create a crater on the surface of Ryugu. This crater will enable the spacecraft to sample more pristine materials from below the space-weathered surface. -

Ma-Lama I Ka Honua Cherish the Earth JOURNAL of the SIERRA CLUB, HAWAI‘I CHAPTER

SIERRA CLUB Ma-lama I Ka Honua Cherish the Earth JOURNAL OF THE SIERRA CLUB, HAWAI‘I CHAPTER A Quarterly Newsletter January - March 2012 Nate’s Adventures Planting Native National Ocean Policy Get Out and Hike Hawai‘i! Chapter Group Reports Nate hikes Kalöpä State Park Rick discusses Kaua‘i’s Opponents to torpedo Great chapter outings Get the latest news on what’s and fi nds natural wonders endemic Hibiscus St. John’s National Ocean Policy? including a new yoga & hike. happening on your island. Page 6 Page 9 Page 10 Pages 13-15, 17 & 21 Pages 12, 16, 18-21 Sierra Club Advances Green Policies by Robert Harris Moving Hawai‘i Beyond Coal to this problem by burning coal on O‘ahu and Maui. The AES Hawai‘i The Hawai‘i Legislature goes back Ever read a report recommending coal plant, in particular, produces to work on January 19, in what looks you limit the amount of seafood approximately 11 percent of the to be a challenging atmosphere for and fi sh you eat because of their energy used on O‘ahu and burns the environment. The state fi nancial toxic mercury content? Although it approximately 650,000 tons of coal situation remains weak after several affects everyone, pregnant women each year. It also spills mercury, acid years of historic budget shortfalls. and children are at greatest risk from gases, and arsenic into our local air As a result, many departments and mercury exposure from seafood and water. programs that serve the environment and fi sh. Exposure to mercury can Dirty coal should have no part are underfunded and understaffed. -

Colonization: a Permanent Habitat for the Colonization of Mars

COLONIZATION A PERMANENT HABITAT FOR THE COLONIZATION OF MARS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master in Engineering Science (Research) in Mechanical Engineering BY MATTHEW HENDER THE UNIVERSITY OF AD ELAIDE SCHOOL OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING SUPERVISOR S – DR. GERALD SCHNEIDER & COLIN HANSEN A u g u s t 2 0 0 9 315°E (45°W) 320°E (40°W) 325°E (35°W) 330°E (30°W) 335°E (25°W) 340°E (20°W) 345°E (15°W) 350°E (10°W) 355°E (5°W) 360°E (0°W) 0° 0° HYDRAOTES CHAOS . llis Dia-Cau Va vi Ra . Camiling Aromatum Chaos . Rypin Chimbote . Mega . IANI MERIDIANI PLANUM* . v Wicklow Windfall Zulanka Pinglo . Oglala Tuskegee . Bamba . CHAOS . Bahn . Locana. Tarata . Spry Manti Balboa ARABIA Huancayo . AUREUM . Groves . Vaals . Conches _ . Sitka Berseba . Kaid . Chinju Lachute . Manah Rakke CHAOS . Stobs . Byske -5° . Airy-0 . -5° Butte. Azusa Kong Timbuktu . Quorn Airy . Creel . Innsbruck XANTHE Wink TERRA TERRA A . Kholm M . Daet S A Ganges .Sfax . Paks H Batoka C Chasma . Rincon I Arsinoes . Glide R P AURORAE CHAOS A Chaos C I S E R M R I N A E R R F G A I T I A R -10° -10° M Pyrrhae C H A O S S Chaos E L L A V MARGARITIFER Eos Mensa* EOS CHASMA Beer -15° -15° alles V L o i r e Osuga Eos TERRA Chaos V a Jones l l e s Vinogradov -20° Lorica Polotsk -20° s Sigli . Kimry . Lebu Valle S Kansk . -

Thedatabook.Pdf

THE DATA BOOK OF ASTRONOMY Also available from Institute of Physics Publishing The Wandering Astronomer Patrick Moore The Photographic Atlas of the Stars H. J. P. Arnold, Paul Doherty and Patrick Moore THE DATA BOOK OF ASTRONOMY P ATRICK M OORE I NSTITUTE O F P HYSICS P UBLISHING B RISTOL A ND P HILADELPHIA c IOP Publishing Ltd 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Multiple copying is permitted in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency under the terms of its agreement with the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 7503 0620 3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data are available Publisher: Nicki Dennis Production Editor: Simon Laurenson Production Control: Sarah Plenty Cover Design: Kevin Lowry Marketing Executive: Colin Fenton Published by Institute of Physics Publishing, wholly owned by The Institute of Physics, London Institute of Physics Publishing, Dirac House, Temple Back, Bristol BS1 6BE, UK US Office: Institute of Physics Publishing, The Public Ledger Building, Suite 1035, 150 South Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19106, USA Printed in the UK by Bookcraft, Midsomer Norton, Somerset CONTENTS FOREWORD vii 1 THE SOLAR SYSTEM 1