Petitioner, Proposed Respondent. Complaint for Action to Stop False

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broiler Chickens

The Life of: Broiler Chickens Chickens reared for meat are called broilers or broiler chickens. They originate from the jungle fowl of the Indian Subcontinent. The broiler industry has grown due to consumer demand for affordable poultry meat. Breeding for production traits and improved nutrition have been used to increase the weight of the breast muscle. Commercial broiler chickens are bred to be very fast growing in order to gain weight quickly. In their natural environment, chickens spend much of their time foraging for food. This means that they are highly motivated to perform species specific behaviours that are typical for chickens (natural behaviours), such as foraging, pecking, scratching and feather maintenance behaviours like preening and dust-bathing. Trees are used for perching at night to avoid predators. The life of chickens destined for meat production consists of two distinct phases. They are born in a hatchery and moved to a grow-out farm at 1 day-old. They remain here until they are heavy enough to be slaughtered. This document gives an overview of a typical broiler chicken’s life. The Hatchery The parent birds (breeder birds - see section at the end) used to produce meat chickens have their eggs removed and placed in an incubator. In the incubator, the eggs are kept under optimum atmosphere conditions and highly regulated temperatures. At 21 days, the chicks are ready to hatch, using their egg tooth to break out of their shell (in a natural situation, the mother would help with this). Chicks are precocial, meaning that immediately after hatching they are relatively mature and can walk around. -

Chicken's Digestive System

Poultry Leader Guide EM082E Level 2 4-H Poultry Leader Notebook Level II Identifying Poultry Feed Ingredients ........................................................3 How to Read Feed Tags ............................................................................7 Boney Birds ............................................................................................ 11 Chicken’s Digestive System ...................................................................17 Poultry Disease Prevention .....................................................................25 Poultry Parasites and Diseases ...............................................................27 Cracking Up—What’s in an Egg? ..........................................................31 Making and Using an Egg Candler ........................................................35 Constructing a Small Incubator ..............................................................39 Determining the Sex of Poultry ..............................................................45 Maternal Bonding and Imprinting (Follow the Leader) .........................49 Preventing Cannibalism ..........................................................................51 The Peck Order .......................................................................................55 Economics of Broiler Production ............................................................59 Poultry Furniture .....................................................................................65 Types of Poultry Housing .......................................................................69 -

The Truth Behind the Labels: Farm Animal Welfare Standards and Labeling Practices a Farm Sanctuary Report Table of Contents

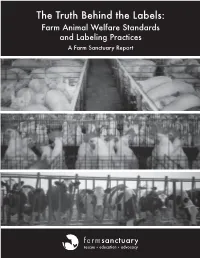

The Truth Behind the Labels: Farm Animal Welfare Standards and Labeling Practices A Farm Sanctuary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Assessing Animal Welfare ............................................................................................................................ 9 4. Assessing Standards Programs ................................................................................................................. 11 5. Product Labeling and Marketing Claims .................................................................................................... 13 6. Industry Quality Assurance Guidelines ....................................................................................................... 21 7. Third-Party Certification Standards ............................................................................................................ 36 8. Assessment of Welfare Standards Programs ............................................................................................. 44 9. Findings ...................................................................................................................................................... 50 10. Appendices ................................................................................................................................................ -

National Chicken Council's Broiler Breeder Welfare Guidelines

NATIONAL CHICKEN COUNCIL ANIMAL WELFARE GUIDELINES AND AUDIT CHECKLIST FOR BROILER BREEDERS Approved by NCC Board of Directors June 2017 NATIONAL CHICKEN COUNCIL 1152 15TH Street NW Suite 430 Washington DC 20005 phone (202) 296-2622 Contents NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines NCC Animal Welfare Audit Checklist Guidance for Conducting Audits Under NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines Standard Contract for Audits Under NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines Appendix NATIONAL CHICKEN COUNCIL ANIMAL WELFARE GUIDELINES The National Chicken Council (NCC) is the national trade association representing vertically integrated broiler producer-processors. NCC recommends the following guidelines to its members to assure the humane treatment of animals and to promote the production of quality products. Preface An animal is considered to be in a good state of welfare “…if (as indicated by scientific evidence) it is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, able to express innate behavior, and if it is not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear, and distress” (OIE). Animals’ physical needs are relatively easily discussed, described, and studied, but their mental states and needs can be more difficult to characterize. We recognize that this is an ongoing discussion and evolving science. With that in mind, the NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines are updated regularly to include new science-based parameters. The NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines have been developed to evaluate the current commercial strains of broiler breeder chickens by auditing how these birds are raised, housed, managed and transported to slaughter at the end of their production cycle. It is important to note that such standards may not be appropriate for other types of poultry as management practices may differ. -

Copyrighted Material

Index growth and development, 28–34 Numerics physical examination, 96–97 30-30 isolation rule, 58 Animal Poison Control Center, 158 2004 USDA backyard chicken study, 11 antibiotics deciding when to use, 228 for E. coli, 168 • A • for fowl pox, 174 for infectious coryza, 169 abdomens, 98–99, 119, 125, 143, 219–220 leg and foot issues, 121 accidents link between drugs and food- decreasing egg production, 139 producing animals, 226 fl ock-mate persecution or for mycoplasmosis, 169–170 cannibalism, 151–154 for respiratory illness, 106 housing and environmental dangers, antibodies, 27–28 161–164 antiseptics, 254–256 nutritional disorders, 154–156 APPPA (American Pastured Poultry poisoning, 156–161 Producers Association), 84 predators, 147–151 ascites, 201, 220 skinny chickens, 136 aspergillosis, 198 stunted growth, 134 aspirin, 121, 307 sudden death, 141 Association of Avian Veterinarians, 211 vitamin and mineral defi ciencies, Auburn University Department of 155–156 Poultry Science, 18 adult birds, 58, 143–144, 240 avian encephalomyelitis (AE), advice, from experts, 17, 209–214 131–132, 172 AE (avian encephalomyelitis), avian infl uenza (AI), 103, 119, 131–132, 172 172–173, 280 AI (avian infl uenza), 103, 119, avian intestinal spirochetosis (AIS), 172–173, 280 166–167 air sacs, 22–23 avian leukosis virus (ALV), 177 AIS (avian intestinal spirochetosis), avian TB (tuberculosis), 53, 166–167, 281 166–167 avian veterinarians, 210–211 albendazole, 309 alcohols, 306 aldehydes, 306 • B • all-in, all-out systems, 59 ALV (avian leukosis virus), 177 -

Guide for Organic Livestock Producers

Guide for Organic Livestock Producers By Linda Coffey and Section 1: Overview of organic certif ication and production Ann H. Baier, National Center for Appropriate Technology (NCAT) Agriculture Specialists CHAPTER 1 November 2012 INTRODUCTION his guide is an overview of the process of becoming certified organic. It is designed to explain the USDA organic regulations as they apply to livestock producers. If Contents you are also producing crops, you will need the “Guide for Organic Producers” to Section 1 Tunderstand the regulations pertaining to the land and to crop production. In addition to Overview of Organic explaining the regulations, both guides give examples of the practices that are allowed Certification and Production Chapters 1-6 ............................................1 for organic production. The first four chapters of the crops guide are essentially the same as the first four of this Section 2 guide; they give an introduction to the National Organic Program (NOP), the organic- Pastures and Hay Crops Chapters 7-14 .......................................24 certification process, the Organic System Plan (OSP), and much more. You can find the crops guide and many other helpful publications at www.attra.ncat.org. If you have already Section 3 read the crops guide or if you already are familiar with the certification process, proceed to Livestock Chapter 5, “Overview of Organic Livestock Systems” in this guide. Chapters 15-25 .....................................44 There are four sections in this guide: Section 4 • Section 1. Overview of organic certification and production Handling of Organic Feed and Livestock Products • Section 2. Pastures and hay crops Chapters 26-30 ....................................75 • Section 3. Livestock Appendix 1 • Section 4. -

Mutilations in Poultry in European Poultry Production Systems Vol

Mutilations in poultry in European poultry production systems Vol. 42 (1), April 2007, Page 35 Mutilations in poultry in European poultry production systems Thea Fiks - van Niekerk and Ingrid de Jong Animal Sciences Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre, NL [email protected] Introduction Mutilations of animals, like beak trimming, have been subject of discussion for many years. Opponents point out the lack of respect for animal integrity and the stress and pain it causes to the animal. Although supporters argue that omitting mutilations can lead to harmful pecking behaviour causing pain and stress as well, there is a growing societal plea for adapting husbandry systems according to the behavioural needs of animals instead of mutilate animals to fit them into current husbandry practices. Better management can contribute to reducing the propensity of feather pecking in laying hens, for example, and increasing knowledge on this issue results in more success for farmers that keep non-mutilated poultry. It is often questioned, however, whether intensive poultry production systems will ever be able to do without mutilations. Many studies have been conducted aiming at finding alternatives for mutilations, but the final solution is still lacking. Some countries have put a ban on specific mutilations. Farmers in these countries have found ways to deal with this, but the discussion on the actual improvement of welfare of birds continuous in those countries as well as discussions on the applicability of those solutions in other countries. Besides finding alternatives for mutilations, research focused on refining the mutilating technology thus minimizing its adverse effects on the animals. -

Canada's Animal Protection Laws

The Health of Animals Act and Regulations: an example of how Canada has failed to protect farmed animals by Rachel Godley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Laws Faculty of Law University of Alberta ©Rachel Godley, 2014 Abstract Farmed animal welfare is an increasingly pressing issue both in Canada and abroad. This thesis surveys the current laws Canada has in place to protect farmed animal welfare. It looks at the Health of Animals Act and regulations as an example of why laws that should protect farmed animals are failing to do so. Pervasive problems with animal welfare legislation are identified and explained, including issues with the fragmented legal framework, and the strength, scope, and interpretation of laws. ii Acknowledgement Thanks to my supervisor Peter Sankoff for his expert insight and ongoing feedback, to my family and friends who have supported me throughout this endeavor, and to the vegan and vegetarian community, who continually remind me of the importance of all our efforts in the fight for animal justice iii Contents CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1. OPENING ACT ................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. ROAD MAP ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Recovering the History of Cockfighting in Kentucky Joseph R

The Kentucky Review Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 2 Winter 1997 Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Recovering the History of Cockfighting in Kentucky Joseph R. Jones University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the United States History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Jones, Joseph R. (1997) "Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Recovering the History of Cockfighting in Kentucky," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 13 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol13/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Recovering the History of Cockfighting in Kentucky Joseph R. Jones For Charles P. Roland, eminent historian and keen observer of Southern life, and the ideal traveling companion A popular encyclopedia of sports from the 1940s1 has a short, clear, and blandly neutral article on cockfighting that describes it as the oldest known sport in which humans use animals. Asians pitted male partridges and quails for centuries before fighting chickens emigrated from India to both East and West. It is a universal amusement (says the encyclopedia), was common in the eastern United States in the late eighteenth century, and has maintained its popularity in America "down through all the generations, despite efforts of authorities to stamp it out. -

Generally Accepted Agricultural and Management Practices for the Care of Farm Animals

Generally Accepted Agricultural and Management Practices for the Care of Farm Animals DRAFT January 20162017 Michigan Commission of Agriculture & Rural Development PO Box 30017 Lansing, MI 48909 (877) 632-1783 www.michigan.gov/mdard In the event of an agricultural pollution emergency such as a chemical/fertilizer spill, manure lagoon breach, etc., the Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development and/or the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality should be contacted at the following emergency telephone numbers: Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development: 800 405-0101 Michigan Department of Environmental Quality: 800 292-4706 If there is not an emergency, but you have questions on the Michigan Right to Farm Act or items concerning a farm operation, please contact the: Michigan Department of Agriculture & Rural Development (MDARD) Right to Farm Program (RTF) P.O. Box 30017 Lansing, Michigan 48909 (517) 284-5619 (517) 335-3329 FAX (877) 632-1783 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERALLY ACCEPTED AGRICULTURAL AND MANAGEMENT PRACTICES FOR THE CARE OF FARM ANIMALS PREFACE……………………………………………………………………….iii OVERVIEW........................…….................................................................1 BEEF CATTLE and BISON....................................................................... 4 DAIRY ...................................................................................................... 10 VEAL ........................................................................................................ 17 SWINE .................................................................................................... -

WOOD COUNTY 4-H POULTRY HANDBOOK an Educational Collection

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION WOOD COUNTY 4-H POULTRY HANDBOOK An Educational Collection Complied by Mandy Causey, Ross County Junior Fair Poultry Superintendent 2019 Wood.osu.edu CFAES provides research and related educational programs to clientele on a nondiscriminatory basis. For more information: go.osu.edu/cfaesdiversity. 4H Pledge I Pledge My head to greater thinking, My heart to greater loyalty, My hands to better service, My health to better living, For my club, my community, my country, and my world. 4H Motto To Make the Best Better 2 INDEX Introduction and History .................................................. 4 Objectives ............................................................................. 7 Quality Assurance ................................................................ 8 Pillars of Character .............................................................. 13 Biosecurity ............................................................................ 17 Management ......................................................................... 18 Record Keeping .................................................................... 20 Medication ............................................................................ 20 Brooding and Housing ........................................................ 23 Hatching Eggs ....................................................................... 27 Sexing .................................................................................... 29 Feed ....................................................................................... -

7042 Federal Register / Vol

7042 Federal Register / Vol. 82, No. 12 / Thursday, January 19, 2017 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE A. Purpose of the Final Rule certified organic operations and to B. Summary of Provisions provide for more effective Agricultural Marketing Service C. Costs and Benefits administration of the National Organic II. General Information Program (NOP) by AMS. One purpose of 7 CFR Part 205 A. Does this Action Apply to Me? III. Background the Organic Foods Production Act of [Document Number AMS–NOP–15–0012; IV. Comments Received 1990 (OFPA) (7 U.S.C. 6501–6522) is to NOP–15–06FR] A. Regulatory Authority of the Final Rule assure consumers that organically B. Regulatory Clarity of the Final Rule produced products meet a consistent RIN 0581–AD44 C. Consumer Education and Outreach and uniform standard (7 U.S.C. 6501). D. International Trade Agreements National Organic Program (NOP); E. Meat and Poultry Imports B. Summary of Provisions Organic Livestock and Poultry V. Related Documents. Specifically, this final rule: Practices VI. Definitions (§ 205.2) A. Description of Regulations 1. Clarifies how producers and AGENCY: Agricultural Marketing Service, B. Discussion of Comments Received handlers participating in the NOP must USDA. VII. Livestock Health Care Practices treat livestock and poultry to ensure ACTION: Final rule. (§ 205.238) their wellbeing. A. Description of Regulations 2. Clarifies when and how certain SUMMARY: The United States Department B. Discussion of Comments Received physical alterations may be performed of Agriculture’s (USDA) Agricultural VIII. Mammalian Living Conditions on organic livestock and poultry in Marketing Service (AMS) is amending (§ 205.39) order to minimize stress.