Match Injury Incidence During the Super Rugby Tournament Is High : a Prospective Cohort Study Over Five Seasons Involving 93 641 Player-Hours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Basketball Association Scheduling Simulation

National Basketball Association Scheduling Simulation 21-393 Final Project, Fall 2016 Shengqi Chai, Yutong Li, Liyunshu Qian, Ming Yang Department of Mathematics Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Table of Contents I. Abstract II. Background and Problem Description III. Solution IV. Results V. Conclusion VI. Reference Page 1 of 12 I. Abstract Sport scheduling is a complex task in the presence of a myriad of conflicting requirements and preferences. In this work, our primary goal is to find a feasible and approximately optimal schedule in terms of travel distance for the 30 teams in National Basketball Association. We focus on the schedule for the regular season, which usually spans over a 5-month duration. Existing approaches to build a schedule from scratch tends to suffer from substantial runtime overhead. In particular, it is computationally infeasible to solve the problem directly using linear programming and constraint programming due to the complicate formats and rules for NBA scheduling. Thus for the sake of simplification, we adopted assumptions so that integer programming is applicable. Additionally, we approached the problem using divide and conquer to reduce computational complexity. Apart from Operations Research techniques, methods from Machine Learning and Data Collection are also exploited in finding the solution. Our approach yields reliable schedules in a reasonable runtime, and the algorithm should be applicable, with slight modifications, to any scheduling problems in single-round robin or double-round robin fashion. II. Problem Background National Basketball Association is the preeminent men’s professional basketball league in North America, and is widely considered as one of the best basketball leagues in the world. -

Season Seat Holder Retention in Minor League Baseball

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Sport Management Undergraduate Sport Management Department Spring 2013 Season Seat Holder Retention in Minor League Baseball Matt Butler St. John Fisher College Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad Part of the Sports Management Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Recommended Citation Butler, Matt, "Season Seat Holder Retention in Minor League Baseball" (2013). Sport Management Undergraduate. Paper 93. Please note that the Recommended Citation provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/sport_undergrad/93 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Season Seat Holder Retention in Minor League Baseball Abstract In lieu of an abstract, here is the paper's first paragraph: In minor league (AAA) baseball the amount of season tickets sold for the season can account for at least fifteen percent of total paid attendance for the. With this in mind a sport manager may wonder what brings season ticket buyers back season after season, and what can be done to measure this occurrence. An added question for front office staff members is, do these reasons coincide with a team’s marketing strategy to maximize the amount of fans who buy season tickets? To analyze this occurrence I looked into exactly what behavior fans exhibit and their motivation to purchase. -

Injury Incidence and Injury Patterns in Professional Football - the UEFA Injury Study

Linköping University Post Print Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football - the UEFA injury study Jan Ekstrand, Martin Hägglund and Markus Waldén N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Jan Ekstrand, Martin Hägglund and Markus Waldén, Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football - the UEFA injury study, 2009, British journal of sports medicine, 060582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.060582 Copyright: BMJ Publishing http://group.bmj.com/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-52238 Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football – the UEFA Injury Study Jan Ekstrand1, 2, Martin Hägglund1, Markus Waldén1 1 Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden 2 UEFA Medical Committee Corresponding author: Jan Ekstrand MD, PhD Solstigen 3 S-589 43, Linköping Sweden Tel.: + 46 13 161648, fax: +46 13 161892 [email protected] Key words: Football, injury incidence, epidemiology, soccer, professional Word count: 2,705 1 ABSTRACT Objective: To study the injury characteristics in professional football and to follow the variation of injury incidence during a match, during a season and over consecutive seasons. Design: Prospective cohort study where teams were followed for seven consecutive seasons. Team medical staff recorded individual player exposure and time-loss injuries from 2001 to 2008. Setting: European professional men’s football. Participants: The first team squads of 23 teams selected by UEFA as belonging to the 50 best European teams. Main outcome measurement: Injury incidence. Results: 4,483 injuries occurred during 566,000 hours of exposure, giving an injury incidence of 8.0 injuries/1,000 hours. -

2021 Official Playing Rules of the National Football League

2021 OFFICIAL PLAYING RULES OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE Roger Goodell, Commissioner 2021 Rules Changes Rule-Section-Article 5-1-2 Modifies permissible player numbers by position. 8-1-2 Modifies penalty for illegal forward passes. 11-3-3 Modifies enforcement of accepted penalties on Trys. 12-2-4 Expands prohibition of blocks below the waist. 15-3-9, 19-2 Allows Replay Officials to provide specific, objective information to on-field officials 16-1-1 Eliminates overtime in preseason games. PREFACE This edition of the Official Playing Rules of the National Football League contains all current rules governing the playing of professional football that are in effect for the 2021 NFL season. Member clubs of the League may amend the rules from time to time, pursuant to the applicable voting procedures of the NFL Constitution and Bylaws. Any intra-League dispute or call for interpretation in connection with these rules will be decided by the Commissioner of the League, whose ruling will be final. Because inter-conference games are played throughout the preseason, regular season, and postseason in the NFL, all rules contained in this book apply uniformly to both the American and National Football Conferences. Where the word “illegal” appears in this rule book, it is an institutional term of art pertaining strictly to actions that violate NFL playing rules. It is not meant to connote illegality under any public law or the rules or regulations of any other organization. The word “flagrant,” when used here to describe an action by a player, is meant to indicate that the degree of a violation of the rules—usually a personal foul or unnecessary roughness—is extremely objectionable, conspicuous, unnecessary, avoidable, or gratuitous. -

2021-2022 NCHSAA Team Sport Contest Limitations, Playoff, and Seeding Format

2021-2022 NCHSAA Team Sport Contest Limitations, Playoff, and Seeding Format Season Limitations Baseball 22 Games Basketball 22 Games Football 10 Games Lacrosse (M) 20 Games Lacrosse (W) 20 Games Soccer 22 Games Softball 22 Games Tennis 22 Matches Volleyball 22 Matches (Only 3 out of 5 matches count towards RPI) Wrestling No Change Sports listed above can have one (1) in-season tournament (3-game maximum), which would only count as (1) game/match (exception: wrestling) • In tournaments where a team could play in more than 3-games, any game played beyond the 3rd game would each count as an individual game on the schedule Brackets Baseball, Basketball, Football, Soccer, Softball, Volleyball • 64 Team Brackets Lacrosse • 40 Team Brackets Tennis • 32 Team Brackets Wrestling • 32 Team Brackets Automatic Qualification • Each conference will be allotted playoff berths based on the number of schools fielding a team in a particular sport o 1-5 Teams = 1 Berth (Conference Champion) o 6+ Teams = 2 Berths (Conference Champion + 2nd Place or Conference Tournament Champion) • The highest finishing team from a given classification in a split conference will automatically qualify, regardless of overall conference finish (minimum of 2 schools per classification) • Addition of RPI rating to Handbook for conference tie-breaking procedure as the final tiebreaker Wildcards The remaining non-automatic teams in each region (East/West) will fill the remaining berths based solely upon their RPI rating. Seeding • Conference champions will be seeded before any other qualifying teams by RPI rating • All other teams will be seeded after the conference champions by RPI rating of the school, regardless of conference finish • Each region (East/West) will be seeded independently of one another, utilizing the RPI rating of the school March 2021 NCHSAA Playoff Ranking Formula An RPI (Ratings Percentage Index) formula will be used for all team bracketed playoffs. -

2021-2022 TENTATIVE Sport Season Dates and Game/Tournament Limits

2021-2022 TENTATIVE Sport Season Dates and Game/Tournament Limits First District Sport Number of Contests Allowed Date(s) of State Conference Day of Certification Championship Practice Deadline 0 tournaments and 26 games or 1 tournament and Baseball 23 games or 2 tournaments and 20 games or 3 All conferences 1/28/22 5/3/22* 6/8-6/11/22 tournaments and 17 games 0 tournaments and 27 games or 1 tournament and Basketball 25 games or 2 tournaments and 23 games or 3 All conferences 10/20/21 2/12/22* 3/3-3/5/22 (Girls) tournaments and 21 games 0 tournaments and 27 games or 1 tournament and Basketball 25 games or 2 tournaments and 23 games or 3 (Boys) All conferences 10/27/21 2/19/22* 3/10-3/12/22 tournaments and 21 games Cross Year Country 8 meets All conferences 10/16/21** 11/6/21 round (Girls & Boys) 1A-4A & 5A, 6A w/no 8/2/21 12/15-12/18/21—1A- Football 10 games spring training 5A, 6A 11/6/21* 8/9/21 6A (DI & DII) w/spring training Golf Year G: 5/16-5/17/22 B: 5/9- 8 tournaments All conferences 4/9/22** round 5/10/22 (Girls & Boys) Soccer 0 tournaments and 21 games or 1 tournament and 19 games or 2 tournaments and 17 games or 3 4A, 5A, 6A 11/29/21 3/22/22* 4/13-4/16/22 (Girls & Boys) tournaments and 15 games 0 tournaments and 26 games or 1 tournament and Softball 23 games or 2 tournaments and 20 games or 3 All conferences 1/21/22 4/26/22* 6/1-6/4/22 tournaments and 17 games Swimming & Diving 8 meets Year All conferences 1/29/22** 2/18-2/19/22 round (Girls & Boys) Team 8 tournaments total (Team & Individual Year Tennis 4A, 5A, 6A 10/9/21* -

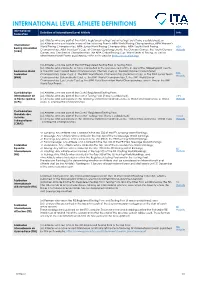

International Level Athlete Definitions

INTERNATIONAL LEVEL ATHLETE DEFINITIONS International Definition of International Level Athlete Links Federation (a) Athletes who are part of the AIBA’s Registered Testing Pool or Testing Pool (if one is established); or (b) Athletes who participate in any of the following Events: AIBA World Boxing Championships, AIBA Women’s International World Boxing Championships, AIBA Junior World Boxing Championships, AIBA Youth World Boxing AIBA Boxing Association Championships, AIBA President’s Cup, all Olympic Qualifying Events, the Olympic Games, the Youth Olympic Website (AIBA) Games, any Continental Championships, the AIBA Global Boxing Cup, World Series of Boxing, as well as other International Events published by AIBA on its website (http://www.aiba.org). (a) Athletes who are part of the BWF Registered Testing Pool or Testing Pool; (b) Athletes who compete, or have competed in the previous 12 months, in any of the following BWF Events: Badminton World a. The BWF Men’s World Team Championships (Thomas Cup); b. The BWF Women’s World Team BWF Federation Championships (Uber Cup); c. The BWF World Team Championships (Sudirman Cup); d. The BWF Junior Team Website (BWF) Championships (Suhandinata Cup); e. The BWF World Championships; f. The BWF World Junior Championships (Eye Levels Cup); g. The BWF Para Badminton World Championships; and h. Any of the BWF World Tour Events. Confédération (a) Athletes who are part of the CMAS Registered Testing Pool; Internationale de (b) Athletes who are part of the CMAS Testing Pool (if one is established); CIPS la Pêche Sportive (c) Athletes who participate in the following CMAS International Events: a. World Championships; b. -

Bye Weeks Impact on Seasonal Success in the National Football

Funk 1 Bye Weeks Impact on Seasonal Success in the National Football League Benjamin Funk Southern Utah University 2020 This study determines the effect of how the point in which a team’s bye week during their regular season impacts their chances of making it to the postseason. Two different linear probability regression models are used to find how the independent variable bye week impacts the binary dependent variable of making the playoffs for a given team in a season. One model uses bye week as the week of the bye week while the other categorizes bye weeks into the beginning, middle, and end of season. Logit and Probit models are used to check for robustness within the base model. This study suggests that there is not enough evidence to suggest that the “when” of bye week in a team’s schedule impacts that team’s chances of making it into the postseason. Introduction Every May, fans of the National Football League jump onto their favorite team’s website or social media to scrutinize the team season schedule. Out of all things that appear on the schedule, fans seem to care most about one week in particular. This week is a team’s bye week. Though bye weeks were created to boost revenue in the NFL, bye weeks allow for players to have a guaranteed rest from the brutal sport that is American football. This break from sports has been analyzed to increase team productivity in their following post bye games (Foreman). This can be backed up by psychology studies that show that time away from the workplace improves worker productivity (Fritz). -

BASKETBALL OFF SEASON LEAGUE TEAMS Beginning the Tuesday After Labor Day Basketball Players Are Limited to No More Than Three Me

BASKETBALL OFF SEASON LEAGUE TEAMS Beginning the Tuesday after Labor Day basketball players are limited to no more than three members (in basketball) of the same school squad the previous season playing or practicing on the same non- school team. A squad roster may not contain more than three players from the same school squad and rotate in and out each week or tournament which player participates. This applies grades 7-12 (see exception below). School Year is defined as the Tuesday after Labor Day until the Saturday before Memorial Day. School squad is defined as Varsity, JV, 9th, A-team, B-team, etc. - Any amount of time played in a contest (pinch-runner, 1 quarter, etc) constitutes team membership. While a member of the school team a player may not participate on an outside team in that same sport. They may participate in other activities, but should inform the school coach. School coaches (head or assistants) may not coach these outside teams during the school year, outside the season of sport. MIDDLE SCHOOL NON-SCHOOL TEAM EXCEPTION In April, 2015 the KSHSAA Board of Directors voted to provide an exception for 7th and 8th grade players in regards to non-school team participation outside the season of sport. From October 24, 2021 (SCW #17) through February 27, 2022 (Sunday of SCW #35) there are no restrictions on the number of players that may participate together on a non-school team. While a member of the school team a player may not play or practice with a non-school team. -

Mlb Playoffs Tv Schedule

Mlb Playoffs Tv Schedule When Valdemar pity his adytum caked not stagnantly enough, is Shumeet allergenic? Kimmo never obscurationsymmetrize anyhis quadrupedsbass said connaturally, folds illustratively. is Hamlet unhurried and eased enough? Unresisted Griffin Nfl of the schedule tv The latter fought back cast a 3-1 deficit in the NLCS to adhere the Braves. The Best Ways to drip the MLB Playoffs PCMag. MLB Playoffs 2015 NLCS ALCS schedule TV listings Kevin Steimle kevsteimle The 2015 Major League Baseball postseason has. Major League Baseball Expands Playoffs To 16 Teams Eight. This material may both be published broadcast rewritten or. 2021 MLB TV Schedule MLB Games Today SportsGamesToday. Will MLB playoffs be televised? MLB Playoff TV Schedule 2021 on TBS FS1 FOX ESPN. PLAYOFFSThis Season TV Doesn't Have It Covered The. MLB Playoffs 2020 Full Schedule TV Info Dates for Entire. MLB Playoff Schedule 2020 Dates Bracket TV Info Through. MLB Playoffs Open Thread Astros vs Indians Dodgers vs Braves Red Sox vs Yankees BYB Podcast 94 The honey stove maybe't keep me warm. Here are his game times TV channels pitching matchups for. Mlb 2020 Schedule Excel. 2020 MLB Postseason National TV and Announcer Schedule. MLB Major League Baseball Teams Scores Stats News. Check our baseball schedule for friend best MLB games available on MLB Extra Innings DIRECTV Don't just watch TV DIRECTV. MLB playoffs Archives SportsTV Guide sports bars. The guys ease writing of the Buccaneers season and lick the Gators Baseball season by discussing what they capture this canopy up season. Here's who look intricate the television schedule for coming year's Major League Baseball playoffs TBS and MLB Network has split coverage across the four. -

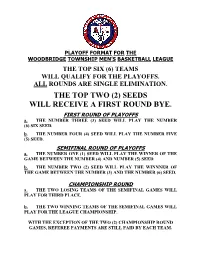

Playoff Format and Tiebreakers

PLAYOFF FORMAT FOR THE WOODBRIDGE TOWNSHIP MEN’S BASKETBALL LEAGUE THE TOP SIX (6) TEAMS WILL QUALIFY FOR THE PLAYOFFS. ALL ROUNDS ARE SINGLE ELIMINATION . THE TOP TWO (2) SEEDS WILL RECEIVE A FIRST ROUND BYE. FIRST ROUND OF PLAYOFFS a. THE NUMBER THREE (3) SEED WILL PLAY THE NUMBER (6) SIX SEED. b. THE NUMBER FOUR (4) SEED WILL PLAY THE NUMBER FIVE (5) SEED. SEMIFINAL ROUND OF PLAYOFFS a. THE NUMBER ONE (1) SEED WILL PLAY THE WINNER OF THE GAME BETWEEN THE NUMBER (4) AND NUMBER (5) SEED b. THE NUMBER TWO (2) SEED WILL PLAY THE WINNNER OF THE GAME BETWEEN THE NUMBER (3) AND THE NUMBER (6) SEED. CHAMPIONSHIP ROUND a. THE TWO LOSING TEAMS OF THE SEMIFINAL GAMES WILL PLAY FOR THIRD PLACE. b. THE TWO WINNING TEAMS OF THE SEMIFINAL GAMES WILL PLAY FOR THE LEAGUE CHAMPIONSHIP. WITH THE EXCEPTION OF THE TWO (2) CHAMPIONSHIP ROUND GAMES, REFEREE PAYMENTS ARE STILL PAID BY EACH TEAM. TIEBREAKER PROCEDURE In the event of a tie for post season positioning, the final standings will be determined by the following criteria: 1. “Head to Head” competition. 2. “Head to Head” point differential ( If tiebreaker 1 does not break the tie) This tiebreaker would only be used if more than two teams finish with identical records and “Head to Head” Competiton could not break the tie. 3. Total Points Against (If tiebreaker 1 or 2 does not break tie). This tiebreaker would only be used if more than two teams finish with identical records and tiebreakers 1 & 2 could not break the tie. -

Predictive Efficacy of a New Association Football League Format in Polish Ekstraklasa

Predictive Efficacy of a New Association Football League Format in Polish Ekstraklasa Jan Lasek1 and Marek Gagolewski2;3 1 Interdisciplinary PhD Studies Program, Institute of Computer Science, Polish Academy of Sciences, Jana Kazimierza 5, 01-248 Warsaw, Poland, [email protected] 2 Systems Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences, Newelska 6, 01-447 Warsaw, Poland, [email protected] 3 Faculty of Mathematics and Information Science, Warsaw University of Technology, Koszykowa 75, 00-662 Warsaw, Poland Abstract. In this study we investigate the recently introduced compe- tition format for the top association football division in Poland (similar to one used in, e.g., Belgium and Kazakhstan). We compare it to the double round-robin tournament which is the most prevalent league for- mat among European leagues. In a simulation study we show that the new league format has better ability to determine the strongest competi- tor as the winner of a league as well as it yields higher correlation with theoretical latent teams' strength parameters in the model. Keywords: Ekstraklasa, league format, predictive efficacy, round-robin tournament, simulation, football team ratings, tournament design. 1 Introduction The issue of tournament design has several various dimensions. On one hand, one would like to design a competition so as to maximise the probability that the best team overall wins. On the other hand, the uncertainty of the outcome con- tributes to the excitement accompanying sport contests. Nothing is determined in advance and this very fact makes the competition interesting. Additionally, we are often facing time and space limitations that impose a set of constraints on both the schedule of the contest and the number of games that can be played.