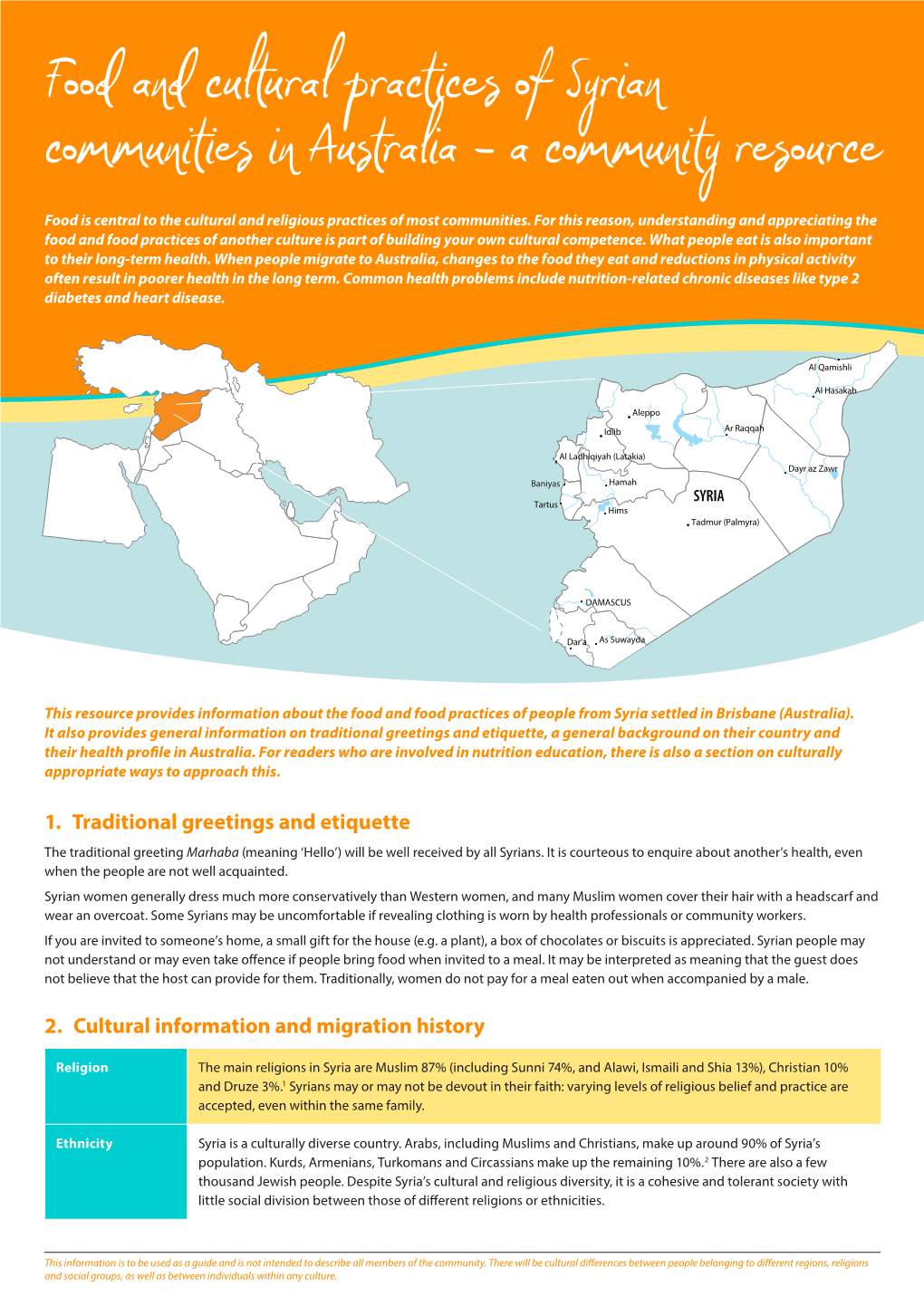

Food and Cultural Practices of Syrian Communities in Australia – a Community Resource Food Is Central to the Cultural and Religious Practices of Most Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menu-Glendale-Dine-In--Dinner.Pdf

SCENES OF LEBANON 304 North Brand Boulevard Glendale, California 91203 818.246.7775 (phone) 818.246.6627 (fax) www.carouselrestaurant.com City of Lebanon Carousel Restaurant is designed with the intent to recreate the dining and entertainment atmosphere of the Middle East with its extensive variety of appetizers, authentic kebabs and specialties. You will be enticed with our Authentic Middle Eastern delicious blend of flavors and spices specific to the Cuisine Middle East. We cater to the pickiest of palates and provide vegetarian menus as well to make all our guests feel welcome. In the evenings, you will be enchanted Live Band with our award-winning entertainment of both singers and and Dance Show Friday & Saturday specialty dancers. Please join us for your business Evenings luncheons, family occasions or just an evening out. 9:30 pm - 1:30 am We hope you enjoy your experience here. TAKE-OUT & CATERING AVAILABLE 1 C A R O U sel S P ec I al TY M E Z as APPETIZERS Mantee (Shish Barak) Mini meat pies, oven baked and topped with a tomato yogurt sauce. 12 VG Vegan Mantee Mushrooms, spinach, quinoa topped with vegan tomato sauce & cashew milk yogurt. 13 Frri (Quail) Pan-fried quail sautéed with sumac pepper and citrus sauce. 15 Frog Legs Provençal Pan-fried frog legs with lemon juice, garlic and cilantro. 15 Filet Mignon Sautée Filet mignon diced, sautéed with onions in tomato & pepper paste. 15 Hammos Filet Sautée Hammos topped with our sautéed filet mignon. 14 Shrimp Kebab Marinated with lemon juice, garlic, cilantro and spices. -

Desayunos Menú 11 11

B r e a k f a s t Close your eyes and visualize de number 11 The game begins There are no rulers or instructions, no script to follow here, the senses are what matters Bowls Summer Chia 6.9€ Chia seed pudding with a touch of summer and strawberries, blueberries and coconut shaving toppings Frida Pasión 7.5€ Yogurt with a touch of coconut, passion fruit, pomegranate, sarraceno wheat Tel Aviv 9.5€ Refreshing and digestive watermelon bowl Acapulco 9.5€ Turmeric and mango bowl Açaí 9.5€ Açaí Bowl Cairo 9.5€ Melon heart bowl Fruit bowl 6.9€ Tostadas Avocado Toast * extra (fried or poached egg) +1,9€ 5.5€ Oil/Butter Toast 2.5€ Ham/turkey and cheese toast 5.5€ Honey and lemon toast 5.9€ Cream cheese and jam toast 5.9€ Dark and with chocolate cocoa toast 5.9€ let's talk about eggs Bodrum Eggs 12.5€ 2 eggs over a natural yogurt bed, dill and pepper Anytime Eggs 8€ French omelette with zucchini, red chili, parmesan cheese and mint Mexican Benedict Eggs 12.5€ Poached eggs with hollandaise sauce over a bed of pumpkin, avocado and a touch of chorizo Zaatar Eggs 12.5€ Eggs with zaatar over greek yogurt Oxaca Omelette 13€ Enoki and shiitake mushrooms, broccoli and a spicy touch Guadalupe Eggs 9.5€ Our lady of Guadalupe style eggs over 2 corn tortillas Bacon + eggs brioche 6.5€ antojitos Gofre 11:11 12€ French Toast 9.5€ Canton pancakes 10.5€ Apple and spices crumble 8.5€ Protein Balls 3€/ud Croissant 3€ Pain au chocolat 3€ Banoffee Middle East pancakes 6.5€ Banana and caramel pancakes A thousand holes crepes 12€ the magic continues Chilaquiles 12€ Dish -

Onions Volume 1 • Number 9

Onions Volume 1 • Number 9 What’s Inside l What’s So Great about Onions? l Selecting and Storing Onions l Varieties of Onions l Fitting Onions into MyPyramid l Recipe Collection l Grow Your Own Onions l Activity Alley What’s So Great about Onions? Rich in Vitamins and Minerals Easy to Use Onions are a source of vitamin C and dietary fiber. Onions can be sliced, As a vegetable, onions are low in fat and calories. chopped, diced, or grated. Onions are rich sources of a number of phytonutri- They mix well with almost ents. These phytonutrients have been found to act any type of food. Raw onions as antioxidants to lower blood pressure and prevent are great in salads and on sand- some kinds of cancer. wiches and hamburgers. Cooked onions are used to season everything Flavorful and Colorful from soups, stews, meats, beans, potatoes to Onions can be red, yellow, green, or white. The taste other vegetable dishes. of onions does not depend on the color. Onions can be sweet or savory. Selecting and Storing Why is Vitamin C Onions Important? At the Market Onions are available year-round. Buy Vitamin C, also known as ascorbic acid, them fresh, dried or frozen. Look for is needed for growth and repair of body hard, firm onions. Onions should be dry tissue. Vitamin C helps to form col- and have small necks. The skin around lagen, a protein used to make skin, scar the onions should be shiny and crackly tissue, and blood vessels. Vitamin C is in feel. -

Race, Rebellion, and Arab Muslim Slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E. Nicholas C. McLeod University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, History of Religion Commons, Islamic Studies Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation McLeod, Nicholas C., "Race, rebellion, and Arab Muslim slavery : the Zanj Rebellion in Iraq, 869 - 883 C.E." (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2381. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2381 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The nivU ersity of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, REBELLION, AND ARAB MUSLIM SLAVERY: THE ZANJ REBELLION IN IRAQ, 869 - 883 C.E. By Nicholas C. McLeod B.A., Bucknell University, 2011 A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Pan-African Studies Department of Pan-African Studies University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Nicholas C. -

TASTES from HOME Recipes from the Refugee Community PREFACE

TASTES FROM HOME Recipes from the Refugee Community PREFACE In writing the articles for this cookbook, I had the privilege and pleasure of speaking with refugees from all over the world who now call Canada home. Sometimes we had the good fortune of meeting in person, but because this project originated during the 2020 pandemic, often we spoke over the phone or through a video call, each of us holed up in our homes. They shared their stories, and they shared their recipes. From one foodie to another, the excitement and pride each person felt about their recipes was palpable. For many, the recipes hold a personal connection to a family member or to a memory, and the food is an indisputable connection to their culture. Each person has a unique story, with different outlooks, challenges, and rewards, but I was struck by one thing they all had in common—a desire to give back to Canada. From the Mexican restaurant owner who plans to employ dozens of Canadians, to the Syrian entrepreneur who donated the proceeds from his chocolate factory to Canadians impacted by wildfires, to the former Governor General who became a figurehead for the country, each person expressed profound gratitude and an eagerness to help the country that took them in. We often hear about refugees in abstract faraway terms, through statistics about the number of people fleeing from one country to another, but in speaking with these 14 people those statistics became humanized and the abstract became real experiences. Their stories are captivating, their recipes are mouthwatering, and I hope you enjoy both in the following pages. -

Café Beckons Middle Eastern Connisseurs

Noura and Raymond Abi Khalil Café beckons Middle Eastern connisseurs NOURA’S CAFÉ For those who adore Middle Eastern food, Noura’s Café is more than where fine dining and parties can take place. Noura’s Café also caters But Noura’s Café is perhaps best known for what is not on its menu. a restaurant, it’s a destination. weddings as well as corporate parties either at the restaurant or other loca- The restaurant serves five authentic Lebanese off-the-menu spe- In Arabic the name “Noura” means “the light,” and the name is a tions. On-line delivery is available via Bite Squad, Uber Eats, and Grubhub. cials daily, drawing clientele from throughout Northeast Florida. The perfect beacon for this one-of-a kind café that specializes in authentic A Lebanon native who emigrated to the United States in the 1980s, café began serving its well-known specials by popular request after Lebanese cuisine. Owned and managed by the husband and wife team Raymond has more than 25 years of food service experience and pre- curious diners smelled fragrant aromas coming from the kitchen at of Raymond and Noura Abi Khahil, the Lakewood café offers the kind viously established two Jacksonville Restaurants – Akel’s Delicatessen 2 p.m. each day when Noura cooked Raymond a special lunch from of dishes mama used to make, if she grew up in Beirut. and Ray’s Café – before opening Noura’s Café with his wife in 2009. family recipes they brought from Lebanon. On the menu are traditional tapas – “mezzah” for the aficionado Before she married Raymond, Noura, who holds a master’s degree in “The customers would ask ‘what are you eating?’ and my husband – including kibbeh ball, za’atar dip, tabbouleh, hummus, baba ga- psychology and previously worked as a banker in Beirut, never envi- – he is such a good salesperson – he would say to me, let the people noush, grape leaves, and falafel – and authentic Arabic Turkish coffee. -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Authentic Lebanese Products Natural & Ethical

Visit our Boutique in Hazmieh Authentic Lebanese Products Natural & Ethical Product Catalog Centre Hourani, RDC, Facing Mekhtariste School, Hazmieh, Lebanon We deliver on Friday! Call us on 05-952153 or 71-783444 Email: [email protected] www.terroirsduliban.com Product Listing At Terroirs du Liban, we are all about providing you with Olives & Oils ................................................................ 2 authentic and traditional Lebanese food products free from artificial additives or preservatives. Spices and Condiments ............................................. 4 You can choose from more than 50 delicious products Seeds ............................................................................ 8 based on the local know-how of Lebanese villages and prepared in a traditional way by rural cooperatives. Ready to Eat ................................................................ 10 Grown under the warm Mediterranean sun, these products reflect the richness of Lebanon’s culture as Snacks .......................................................................... 11 well as its generous and welcoming cuisine. Jams & spreads ........................................................... 12 We guarantee your satisfaction with Fairtrade certified products. This means that our products follow strict Distillates .................................................................... 16 social, economic and quality standards. They are: Syrups .......................................................................... 17 - 100% natural -

The Postprandial Glycemic and Insulinemic Effects of Three Cooked Vegetables

The Postprandial Glycemic and Insulinemic Effects of Three Cooked Vegetables: Corchorus Olitorius, Spinacia Oleracea, and Daucus Carota on Steamed White Rice Ahmad Faqih*1 and Buthaina Al-Khatib2 Abstract Background: Eatingcooked vegetables with rice is quite common in Jordan and worldwide. Dietary fibers of vegetables are expected to play a role in the glycemic control of meals. Aim: To study the postprandial glycemic and insulinemic effect of three cooked vegetables: mulukhiyah leaves (Corchorus olitorius), spinach (Spinacia oleracea) and carrots (Daucus carota). Methods: The postprandial glycemic and insulinemic effect of the threecooked vegetables on steamed rice were studied by runningtheoral glucose tolerance tests on apparently healthy young adults, each of who served as his own control, using white bread as the reference. Insulin sensitivity was measured by calculating the composite insulin sensitivity index. Results: The glycemic index (GI) of rice (84.2±10.5%) ingested with chicken broth was significantly lowered only by eating 120 g of mulukhiyah leaves (ML) and not by either carrots or spinach. The insulinemic index (II) of steamed white rice eaten with broth was significantly lowered by120 g of ML (61.7± 9.2%) and 150 g of spinach (42.9± 9.0%). Insulin sensitivity was only improved by spinach. All results are expressed as means ± SEM and are considered statistically significant at P<0.05. The results also suggested that there was no significant difference between the calculated relative GI and relative II responses of the three cooked vegetables at the two assigned levels, each eaten with rice and broth compared to the corresponding GI or the II values of the individual foods from which they were composed of. -

MENU Prix TTC En Euros

Cold Mezes Hot Mezes Hummus (vg) ............................... X Octopus on Fire ............................ X Lamb Shish Fistuk (h) .................. X Chickpeas, tahini, lemon, garlic, Smoked hazelnut, red pepper sauce Green pistachio, tomato, onion, green sumac, olive oil, pita bread chilli pepper, sumac salad Moroccan Rolls ............................. X Tzatziki (v) ................................... X Filo pastry, pastirma, red and yellow Garlic Tiger Prawns ...................... X Fresh yogurt, dill oil, pickled pepper bell, smoked cheese, harissa Garlic oil, shaved fennel salad, red cucumber, dill tops, pita bread yoghurt chilli pepper, zaatar Babaganoush (vg) ......................... X Pastirma Mushrooms .................... X Spinach Borek (v) ......................... X Smoked aubergine, pomegranate Cured beef, portobello and oysters Filo pastry, spinach, feta cheese, pine molasses, tahini, fresh mint, diced mushrooms, poached egg yolk, sumac nuts, fresh mint tomato, pita bread Roasted Cauliflower (v) ................ X Chicken Mashwyia ........................ X Taramosalata ................................ X Turmeric, mint, dill, fried capers, Wood fire chicken thighs, pickled Cod roe rock, samphire, bottarga, garlic yoghurt onion, mashwyia on a pita bread lemon zest, spring onion, pita bread Grilled Halloumi (v) ..................... X Meze Platter .................................. X Beetroot Borani (v) ...................... X Chargrilled courgette, kalamata Hummus, Tzatziki, Babaganoush, Walnuts, nigella seeds, -

Food-Based Dietary Guidelines Around the World: Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Countries

nutrients Review Food-Based Dietary Guidelines around the World: Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern Countries Concetta Montagnese 1,*, Lidia Santarpia 2,3, Fabio Iavarone 2, Francesca Strangio 2, Brigida Sangiovanni 2, Margherita Buonifacio 2, Anna Rita Caldara 2, Eufemia Silvestri 2, Franco Contaldo 2,3 and Fabrizio Pasanisi 2,3 1 Epidemiology Unit, IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori “Fondazione G. Pascale”, 80131 Napoli, Italy 2 Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Department of Clinical Medicine and Surgery, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (L.S.); [email protected] (F.I.); [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.R.C.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (F.P.) 3 Interuniversity Center for Obesity and Eating Disorders, Department of Clinical Nutrition and Internal Medicine, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +0039-081-746-2333 Received: 28 April 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 13 June 2019 Abstract: In Eastern Mediterranean countries, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies coexist with overnutrition-related diseases, such as obesity, heart disease, diabetes and cancer. Many Mediterranean countries have produced Food-Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDGs) to provide the general population with indications for healthy nutrition and lifestyles. This narrative review analyses Eastern Mediterranean countries’ FBDGs and discusses their pictorial representations, food groupings and associated messages on healthy eating and behaviours. In 2012, both the WHO and the Arab Center for Nutrition developed specific dietary guidelines for Arab countries. In addition, seven countries, representing 29% of the Eastern Mediterranean Region population, designated their national FBDGs. -

Dessert Menu

MADO MENU DESSERTS From Karsambac to Mado Ice cream: Flavor’s Journey throughout the History From Karsambac to Mado Ice-cream: Flavors’ Journey throughout the History Mado Ice-cream, which has earned well-deserved fame all over the world with its unique flavor, has a long history of 300 years. This is the history of the “step by step” transformation of a savor tradition called Karsambac (snow mix) that entirely belongs to Anatolia. Karsambac is made by mixing layers of snow - preserved on hillsides and valleys via covering them with leaves and branches - with fruit extracts in hot summer days. In time, this mixture was enriched with other ingredients such as milk, honey, and salep, and turned into the well-known unique flavor of today. The secret of the savor of Mado Ice-cream lies, in addition to this 300 year-old tradition, in the climate and geography where it is produced. This unique flavor is obtained by mixing the milk of animals that are fed on thyme, milk vetch and orchid flowers on the high plateaus on the hillsides of Ahirdagi, with sahlep gathered from the same area. All fruit flavors of Maras Ice-cream are also made through completely natural methods, with pure cherries, lemons, strawberries, oranges and other fruits. Mado is the outcome of the transformation of our traditional family workshop that has been ice-cream makers for four generations, into modern production plants. Ice-cream and other products are prepared under cutting edge hygiene and quality standards in these world-class modern plants and are distributed under necessary conditions to our stores across Turkey and abroad; presented to the appreciation of your gusto, the esteemed gourmet.