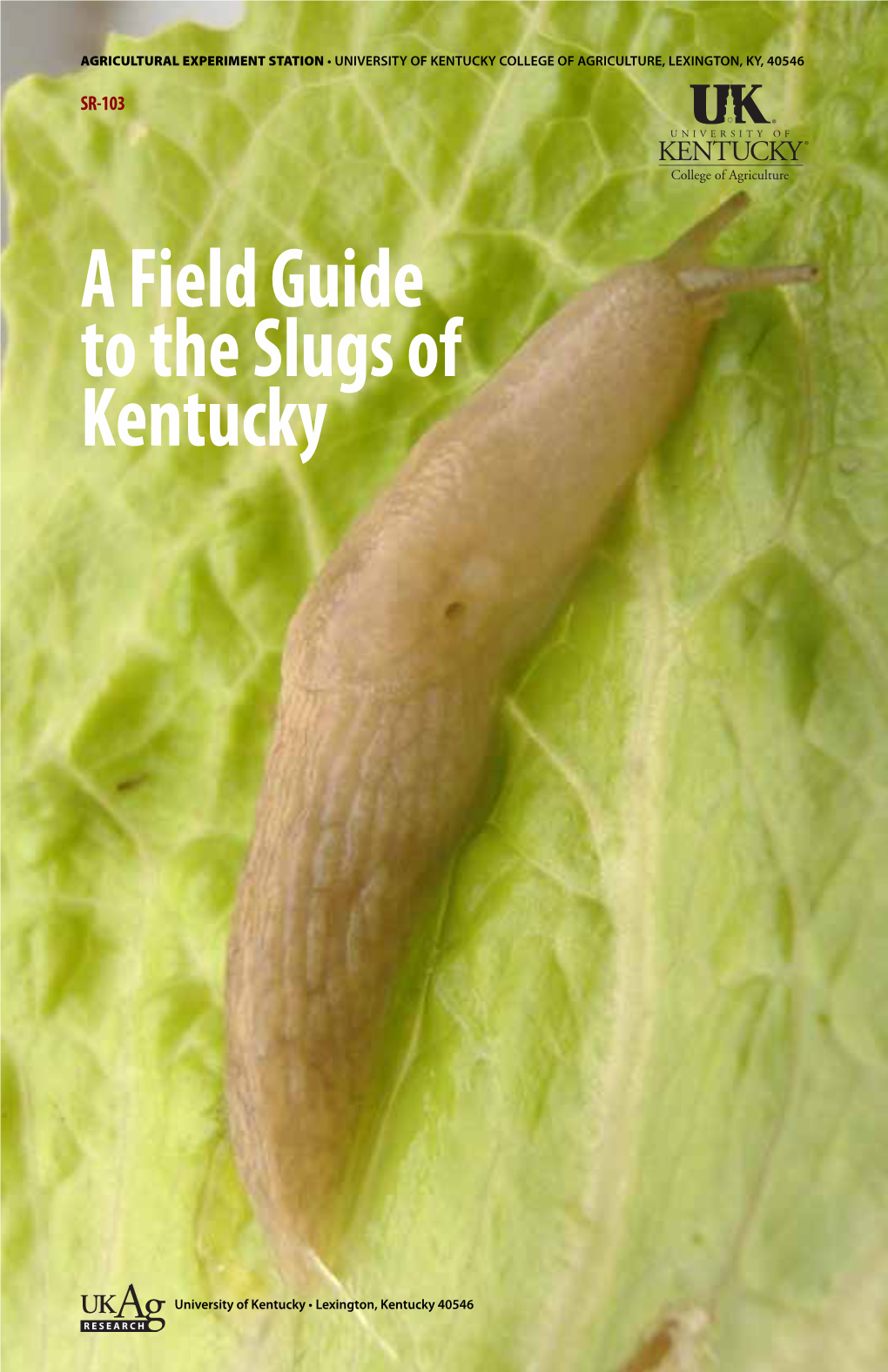

A Field Guide to the Slugs of Kentucky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Alien Slug Could Spread Further with Climate Change

Invasive alien slug could spread further with climate change A recent study sheds light on why some alien species are more likely to become invasive than others. The research in Switzerland found that the alien Spanish slug is better able to survive under changing environmental conditions than the native 20 December 2012 Black slug, thanks to its robust ‘Jack-of-all-trades’ nature. Issue 311 Subscribe to free weekly News Alert Invasive alien species are animals and plants that are introduced accidently or deliberately into a natural environment where they are not normally found and become Source: Knop, E. & dominant in the local ecosystem. They are a potential threat to biodiversity, especially if they Reusser, N. (2012) Jack- compete with or negatively affect native species. There is concern that climate change will of-all-trades: phenotypic encourage more invasive alien species to become established and, as such, a better plasticitiy facilitates the understanding is needed of why and how some introduced species become successful invasion of an alien slug invaders. species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological The study compared the ‘phenotypic plasticity’ of a native and a non-native slug species in Sciences. 279: 4668-4676. Europe. Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of an organism to alter its characteristics or traits Doi: (including behaviour) in response to changing environmental conditions. 10.1098/rspb.2012.1564. According to a framework used to understand invasive plants, invaders can benefit from phenotypic plasticity in three ways. Firstly, they are robust and can maintain fitness in Contact: varied, stressful situations, and are described as ‘Jack-of-all-trades’. -

The Slugs of Britain and Ireland: Undetected and Undescribed Species Increase a Well-Studied, Economically Important Fauna by More Than 20%

The Slugs of Britain and Ireland: Undetected and Undescribed Species Increase a Well-Studied, Economically Important Fauna by More Than 20% Ben Rowson1*, Roy Anderson2, James A. Turner1, William O. C. Symondson3 1 National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom, 2 Conchological Society of Great Britain & Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom, 3 Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff, Wales, United Kingdom Abstract The slugs of Britain and Ireland form a well-studied fauna of economic importance. They include many widespread European species that are introduced elsewhere (at least half of the 36 currently recorded British species are established in North America, for example). To test the contention that the British and Irish fauna consists of 36 species, and to verify the identity of each, a species delimitation study was conducted based on a geographically wide survey. Comparisons between mitochondrial DNA (COI, 16S), nuclear DNA (ITS-1) and morphology were investigated with reference to interspecific hybridisation. Species delimitation of the fauna produced a primary species hypothesis of 47 putative species. This was refined to a secondary species hypothesis of 44 species by integration with morphological and other data. Thirty six of these correspond to the known fauna (two species in Arion subgenus Carinarion were scarcely distinct and Arion (Mesarion) subfuscus consisted of two near-cryptic species). However, by the same criteria a further eight previously undetected species (22% of the fauna) are established in Britain and/or Ireland. Although overlooked, none are strictly morphologically cryptic, and some appear previously undescribed. Most of the additional species are probably accidentally introduced, and several are already widespread in Britain and Ireland (and thus perhaps elsewhere). -

The Slugs of Bulgaria (Arionidae, Milacidae, Agriolimacidae

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK INSTYTUT ZOOLOGII ANNALES ZOOLOGICI Tom 37 Warszawa, 20 X 1983 Nr 3 A n d rzej W ik t o r The slugs of Bulgaria (A rionidae , M ilacidae, Limacidae, Agriolimacidae — G astropoda , Stylommatophora) [With 118 text-figures and 31 maps] Abstract. All previously known Bulgarian slugs from the Arionidae, Milacidae, Limacidae and Agriolimacidae families have been discussed in this paper. It is based on many years of individual field research, examination of all accessible private and museum collections as well as on critical analysis of the published data. The taxa from families to species are sup plied with synonymy, descriptions of external morphology, anatomy, bionomics, distribution and all records from Bulgaria. It also includes the original key to all species. The illustrative material comprises 118 drawings, including 116 made by the author, and maps of localities on UTM grid. The occurrence of 37 slug species was ascertained, including 1 species (Tandonia pirinia- na) which is quite new for scientists. The occurrence of other 4 species known from publications could not bo established. Basing on the variety of slug fauna two zoogeographical limits were indicated. One separating the Stara Pianina Mountains from south-western massifs (Pirin, Rila, Rodopi, Vitosha. Mountains), the other running across the range of Stara Pianina in the^area of Shipka pass. INTRODUCTION Like other Balkan countries, Bulgaria is an area of Palearctic especially interesting in respect to malacofauna. So far little investigation has been carried out on molluscs of that country and very few papers on slugs (mostly contributions) were published. The papers by B a b o r (1898) and J u r in ić (1906) are the oldest ones. -

Molluscs of the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area

Molluscs of the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area S a b i n e F ISCHER & M i c h a e l D UDA Abstract: Research in the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area (DWA) in the southwest of Lower Austria is mainly concerned with the inventory of flora, fauna and habitats, interdisciplinary monitoring and studies on ecological disturbances and process dynamics. During a four-year qualitative study of non-marine molluscs, 96 sites within the DWA and nearby nature reserves were sampled in cooperation with the “Alpine Land Snails Working Group” located at the Natural History Museum of Vienna. Altogether, 84 taxa were recorded (72 land snails, 12 water snails and mussels) including four endemics and seven species listed in the Austrian Red List of Molluscs. A reference collection (empty shells) of molluscs, which is stored at the DWA administration, was created. This project was the first systematic survey of mollusc fauna in the DWA. Further sampling might provide additional information in the future, particularly for Hydrobiidae in springs and caves, where detailed analyses (e.g. anatomical and genetic) are needed. Key words: Wilderness Dürrenstein, Primeval forest, Benign neglect, Non-intervention management, Mollusca, Snails, Alpine endemics. Introduction manifold species living in the wilderness area – many of them “refugees”, whose natural habitats have almost In concordance with the IUCN guidelines, research is disappeared in today’s over-cultivated landscape. mandatory for category I wilderness areas. However, it may not disturb the natural habitats and communities of the nature reserve. Research in the Dürrenstein The Dürrenstein Wilderness Area Wilderness Area (DWA) focuses on providing invento- (DWA) ries of flora and fauna, on interdisciplinary monitoring The Dürrenstein Wilderness Area (DWA) was as well as on ecological disturbances and process dynamics. -

December 2011

Ellipsaria Vol. 13 - No. 4 December 2011 Newsletter of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society Volume 13 – Number 4 December 2011 FMCS 2012 WORKSHOP: Incorporating Environmental Flows, 2012 Workshop 1 Climate Change, and Ecosystem Services into Freshwater Mussel Society News 2 Conservation and Management April 19 & 20, 2012 Holiday Inn- Athens, Georgia Announcements 5 The FMCS 2012 Workshop will be held on April 19 and 20, 2012, at the Holiday Inn, 197 E. Broad Street, in Athens, Georgia, USA. The topic of the workshop is Recent “Incorporating Environmental Flows, Climate Change, and Publications 8 Ecosystem Services into Freshwater Mussel Conservation and Management”. Morning and afternoon sessions on Thursday will address science, policy, and legal issues Upcoming related to establishing and maintaining environmental flow recommendations for mussels. The session on Friday Meetings 8 morning will consider how to incorporate climate change into freshwater mussel conservation; talks will range from an overview of national and regional activities to local case Contributed studies. The Friday afternoon session will cover the Articles 9 emerging science of “Ecosystem Services” and how this can be used in estimating the value of mussel conservation. There will be a combined student poster FMCS Officers 47 session and social on Thursday evening. A block of rooms will be available at the Holiday Inn, Athens at the government rate of $91 per night. In FMCS Committees 48 addition, there are numerous other hotels in the vicinity. More information on Athens can be found at: http://www.visitathensga.com/ Parting Shot 49 Registration and more details about the workshop will be available by mid-December on the FMCS website (http://molluskconservation.org/index.html). -

On the Distribution and Food Preferences of Arion Subfuscus (Draparnaud, 1805)

Vol. 16(2): 61–67 ON THE DISTRIBUTION AND FOOD PREFERENCES OF ARION SUBFUSCUS (DRAPARNAUD, 1805) JAN KOZ£OWSKI Institute of Plant Protection, National Research Institute, W³adys³awa Wêgorka 20, 60-318 Poznañ, Poland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: In recent years Arion subfuscus (Drap.) is increasingly often observed in agricultural crops. Its abun- dance and effect on winter oilseed rape crops were studied. Its abundance was found to be much lower than that of Deroceras reticulatum (O. F. Müll.). Preferences of A. subfuscus to oilseed rape and 19 other herbaceous plants were determined based on multiple choice tests in the laboratory. Indices of acceptance (A.I.), palat- ability (P.I.) and consumption (C.I.) were calculated for the studied plant species; accepted and not accepted plant species were identified. A. subfuscus was found to prefer seedlings of Brassica napus, while Chelidonium maius, Euphorbia helioscopia and Plantago lanceolata were not accepted. KEY WORDS: Arion subfuscus, abundance, oilseed rape seedlings, herbaceous plants, acceptance of plants INTRODUCTION Pulmonate slugs are seroius pests of plants culti- common (RIEDEL 1988, WIKTOR 2004). It lives in low- vated in Poland and in other parts of western and cen- land and montane forests, shrubs, on meadows, tral Europe (GLEN et al. 1993, MESCH 1996, FRANK montane glades and sometimes even in peat bogs. Re- 1998, MOENS &GLEN 2002, PORT &ESTER 2002, cently it has been observed to occur synanthropically KOZ£OWSKI 2003). The most important pest species in such habitats as ruins, parks, cemeteries, gardens include Deroceras reticulatum (O. F. Müller, 1774), and and margins of cultivated fields. -

BRYOLOGICAL INTERACTION-Chapter 4-6

65 CHAPTER 4-6 INVERTEBRATES: MOLLUSKS Figure 1. Slug on a Fissidens species. Photo by Janice Glime. Mollusca – Mollusks Glistening trails of pearly mucous criss-cross mats and also seemed to be a preferred food. Perhaps we need to turfs of green, signalling the passing of snails and slugs on searach at night when the snails and slugs are more active. the low-growing bryophytes (Figure 1). In California, the white desert snail Eremarionta immaculata is more common on lichens and mosses than on other plant detritus and rocks (Wiesenborn 2003). Wiesenborn suggested that the snails might find more food and moisture there. Are these mollusks simply travelling from one place to another across the moist moss surface, or do they have a more dastardly purpose for traversing these miniature forests? Quantitative information on snails and slugs among bryophytes is scarce, and often only mentions that bryophytes are abundant in the habitat (e.g. Nekola 2002), but we might be able to glean some information from a study by Grime and Blythe (1969). In collections totalling 82.4 g of moss, they examined snail populations in a 0.75 m2 plot each morning on 7, 8, 9, & 12 September 1966. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum (Figure 2), numbered 0, 7, 2, and 6 on those days, respectively, with weights of Figure 2. The copse snail, Arianta arbustorum, in 0.0, 8.5, 2.4, & 7.3 per 100 g dry mass of moss. They were Stockholm, Sweden. Photo by Håkan Svensson through most abundant on the stinging nettle, Urtica dioica, which Wikimedia Commons. -

Fauna of New Zealand Ko Te Aitanga Pepeke O Aotearoa

aua o ew eaa Ko te Aiaga eeke o Aoeaoa IEEAE SYSEMAICS AISOY GOU EESEAIES O ACAE ESEAC ema acae eseac ico Agicuue & Sciece Cee P O o 9 ico ew eaa K Cosy a M-C aiièe acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa EESEAIE O UIESIIES M Emeso eame o Eomoogy & Aima Ecoogy PO o ico Uiesiy ew eaa EESEAIE O MUSEUMS M ama aua Eiome eame Museum o ew eaa e aa ogaewa O o 7 Weigo ew eaa EESEAIE O OESEAS ISIUIOS awece CSIO iisio o Eomoogy GO o 17 Caea Ciy AC 1 Ausaia SEIES EIO AUA O EW EAA M C ua (ecease ue 199 acae eseac Mou Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 38 Naturalised terrestrial Stylommatophora (Mousca Gasooa Gay M ake acae eseac iae ag 317 amio ew eaa 4 Maaaki Whenua Ρ Ε S S ico Caeuy ew eaa 1999 Coyig © acae eseac ew eaa 1999 o a o is wok coee y coyig may e eouce o coie i ay om o y ay meas (gaic eecoic o mecaica icuig oocoyig ecoig aig iomaio eiea sysems o oewise wiou e wie emissio o e uise Caaoguig i uicaio AKE G Μ (Gay Micae 195— auase eesia Syommaooa (Mousca Gasooa / G Μ ake — ico Caeuy Maaaki Weua ess 1999 (aua o ew eaa ISS 111-533 ; o 3 IS -7-93-5 I ie 11 Seies UC 593(931 eae o uIicaio y e seies eio (a comee y eo Cosy usig comue-ase e ocessig ayou scaig a iig a acae eseac M Ae eseac Cee iae ag 917 Aucka ew eaa Māoi summay e y aco uaau Cosuas Weigo uise y Maaaki Weua ess acae eseac O o ico Caeuy Wesie //wwwmwessco/ ie y G i Weigo o coe eoceas eicuaum (ue a eigo oaa (owe (IIusao G M ake oucio o e coou Iaes was ue y e ew eaIa oey oa ue oeies eseac -

The Slugs of Florida (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-087 The Slugs of Florida (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1 Lionel A. Stange2 Introduction washed under running water to remove excess mucus before placing in preservative. Notes on the color of Florida has a depauparate slug fauna, having the mucus secreted by the living slug would be only three native species which belong to three helpful in identification. different families. Eleven species of exotic slugs have been intercepted by USDA and DPI quarantine Biology inspectors, but only one is known to be established. Some of these, such as the gray garden slug Slugs are hermaphroditic, but often the sperm (Deroceras reticulatum Müller), spotted garden slug and ova in the gonads mature at different times (Limax maximus L.), and tawny garden slug (Limax (leading to male and female phases). Slugs flavus L.), are very destructive garden and greenhouse commonly cross fertilize and may have elaborate pests. Therefore, constant vigilance is needed to courtship dances (Karlin and Bacon 1961). They lay prevent their establishment. Some veronicellid slugs gelatinous eggs in clusters that usually average 20 to are becoming more widely distributed (Dundee 30 on the soil in concealed and moist locations. Eggs 1977). The Brazilian Veronicella ameghini are round to oval, usually colorless, and sometimes (Gambetta) has been found at several Florida have irregular rows of calcium particles which are localities (Dundee 1974). This velvety black slug absorbed by the embryo to form the internal shell should be looked for under boards and debris in (Karlin and Naegele 1958). -

Distribution of Angiostrongylus Vasorum and Its

Aziz et al. Parasites & Vectors (2016) 9:56 DOI 10.1186/s13071-016-1338-3 RESEARCH Open Access Distribution of Angiostrongylus vasorum and its gastropod intermediate hosts along the rural–urban gradient in two cities in the United Kingdom, using real time PCR Nor Azlina A. Aziz1,2*, Elizabeth Daly1, Simon Allen1,3, Ben Rowson4, Carolyn Greig3, Dan Forman3 and Eric R. Morgan1 Abstract Background: Angiostrongylus vasorum is a highly pathogenic metastrongylid nematode affecting dogs, which uses gastropod molluscs as intermediate hosts. The geographical distribution of the parasite appears to be heterogeneous or patchy and understanding of the factors underlying this heterogeneity is limited. In this study, we compared the species of gastropod present and the prevalence of A. vasorum along a rural–urban gradient in two cities in the south-west United Kingdom. Methods: The study was conducted in Swansea in south Wales (a known endemic hotspot for A. vasorum) and Bristol in south-west England (where reported cases are rare). In each location, slugs were sampled from nine sites across three broad habitat types (urban, suburban and rural). A total of 180 slugs were collected in Swansea in autumn 2012 and 338 in Bristol in summer 2014. A 10 mg sample of foot tissue was tested for the presence of A. vasorum by amplification of the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS-2) using a previously validated real-time PCR assay. Results: There was a significant difference in the prevalence of A. vasorum in slugs between cities: 29.4 % in Swansea and 0.3 % in Bristol. In Swansea, prevalence was higher in suburban than in rural and urban areas. -

Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L

EENY-494 Terrestrial Slugs of Florida (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L. Capinera2 Introduction Florida has only a few terrestrial slug species that are native (indigenous), but some non-native (nonindigenous) species have successfully established here. Many interceptions of slugs are made by quarantine inspectors (Robinson 1999), including species not yet found in the United States or restricted to areas of North America other than Florida. In addition to the many potential invasive slugs originating in temperate climates such as Europe, the traditional source of invasive molluscs for the US, Florida is also quite susceptible to invasion by slugs from warmer climates. Indeed, most of the invaders that have established here are warm-weather or tropical species. Following is a discus- sion of the situation in Florida, including problems with Figure 1. Lateral view of slug showing the breathing pore (pneumostome) open. When closed, the pore can be difficult to locate. slug identification and taxonomy, as well as the behavior, Note that there are two pairs of tentacles, with the larger, upper pair ecology, and management of slugs. bearing visual organs. Credits: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS Biology as nocturnal activity and dwelling mostly in sheltered Slugs are snails without a visible shell (some have an environments. Slugs also reduce water loss by opening their internal shell and a few have a greatly reduced external breathing pore (pneumostome) only periodically instead of shell). The slug life-form (with a reduced or invisible shell) having it open continuously. Slugs produce mucus (slime), has evolved a number of times in different snail families, which allows them to adhere to the substrate and provides but this shell-free body form has imparted similar behavior some protection against abrasion, but some mucus also and physiology in all species of slugs. -

Impact of Dietary Diversification on Invasive Slugs and Biological Control with Notes on Slug Species of Kentucky

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 IMPACT OF DIETARY DIVERSIFICATION ON INVASIVE SLUGS AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL WITH NOTES ON SLUG SPECIES OF KENTUCKY Anna K. Thomas University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Thomas, Anna K., "IMPACT OF DIETARY DIVERSIFICATION ON INVASIVE SLUGS AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL WITH NOTES ON SLUG SPECIES OF KENTUCKY" (2010). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 35. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/35 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS IMPACT OF DIETARY DIVERSIFICATION ON INVASIVE SLUGS AND BIOLOGICAL CONTROL WITH NOTES ON SLUG SPECIES OF KENTUCKY Increasing introductions of non-native terrestrial slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) are a concern to North American regulatory agencies as these generalists impact the yield and reduce the aesthetic value of crop plants. Understanding how the increase in diversification in North American cropping systems affects non-native gastropods and finding effective biological control options are imperative for pest management; however, little research has been done in this area. This study tested the hypothesis that dietary diversification affects the biological control capacity of a generalist predator and allows the slug pest Deroceras reticulatum (Müller) (Stylommatophora: Agriolimacidae) to more effectively fulfill its nutritional requirements.